This region is dominated by the Arnhem Escarpment, a vast range of rocky hills home to thousands of rock art galleries, some more than 30,000 years old. The majority of rock paintings here are figurative and these have influenced the style of bark painting in the region.

Yirawala is one of the major artists in Australian art history. He played a leading role in promoting the acceptance of Aboriginal art as ‘art’ rather than simply ‘ethnographic material’.

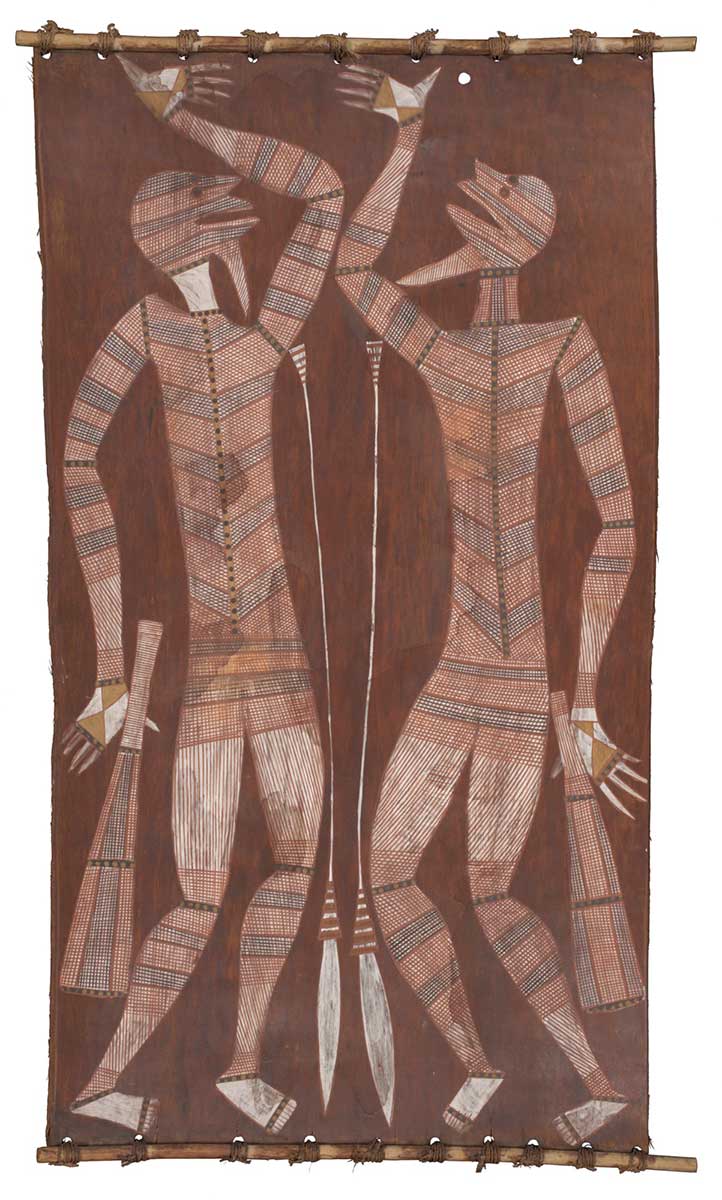

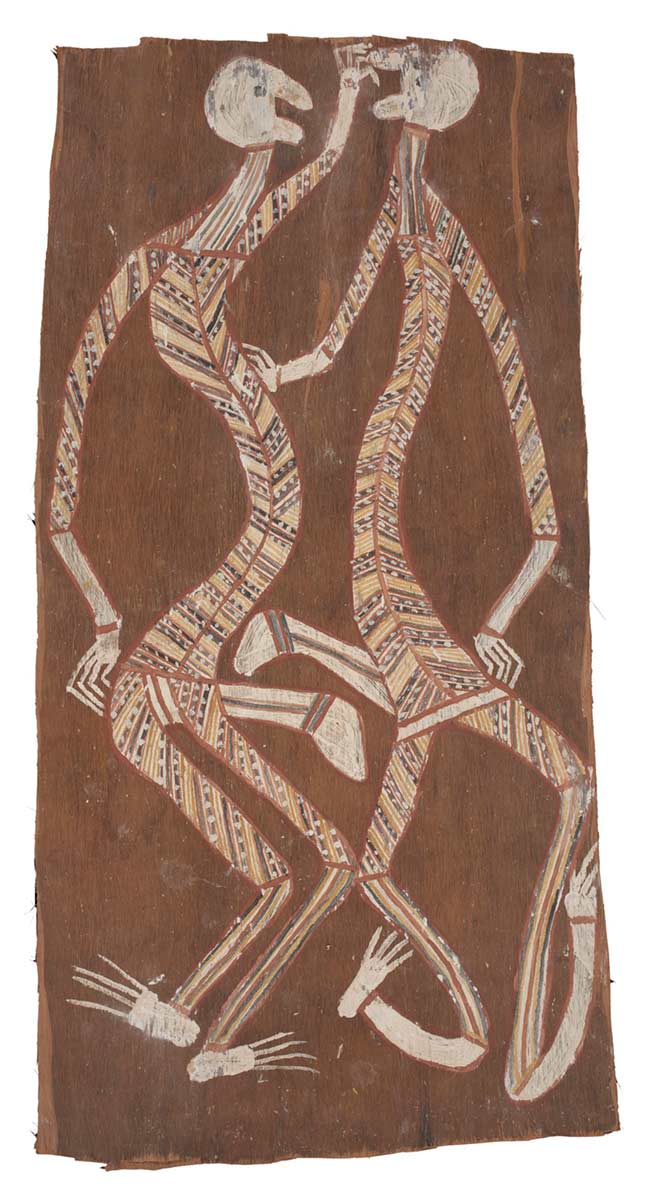

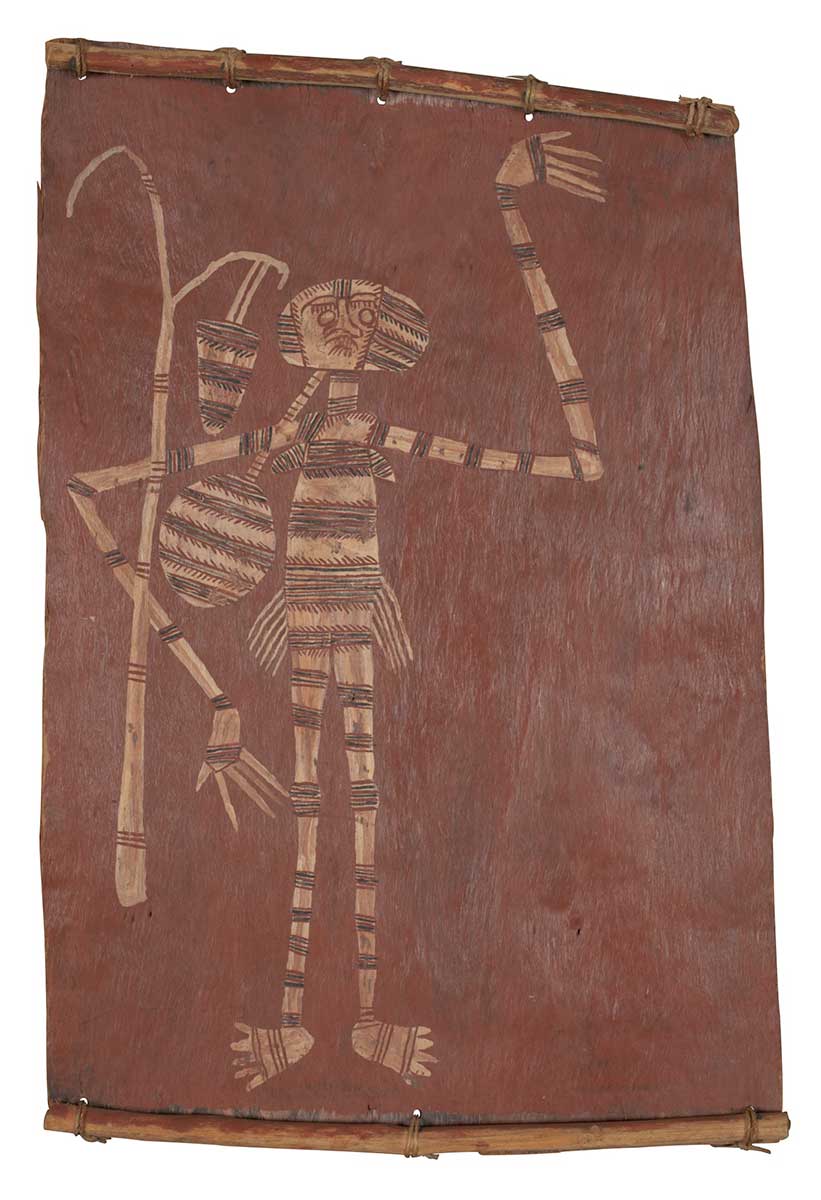

Yirawala’s impetus to paint for the public stemmed from a need to reveal his culture to non-Indigenous Australians so that it could be understood and respected. He was a gifted painter of high ritual authority, which allowed him to innovate on the art traditions of the Kuninjku people. Among his main innovations are his exquisitely rendered variations on conventional rarrk (crosshatched) clan patterns.

Although Yirawala had an extensive repertoire of subjects at his command, the majority of his work is associated with the major regional ceremonies, especially the Mardayin, which involves both Duwa and Yirridjdja moities.

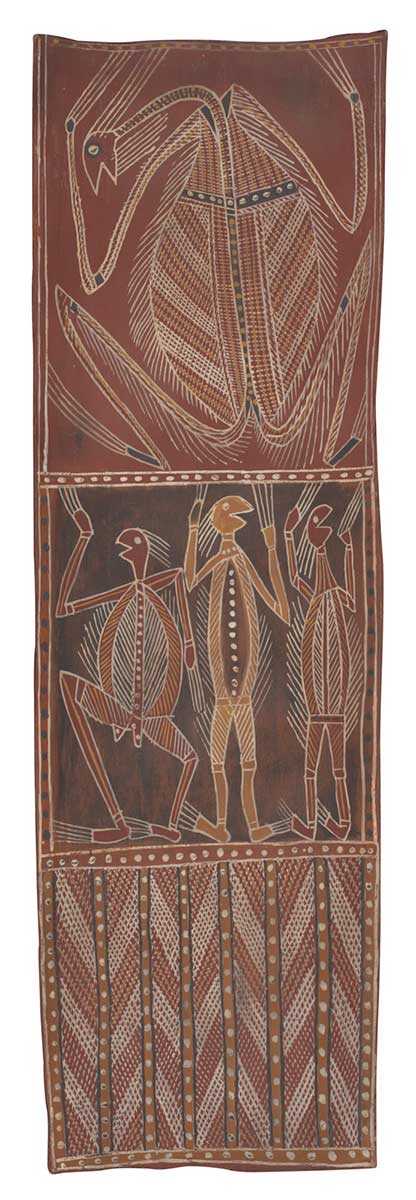

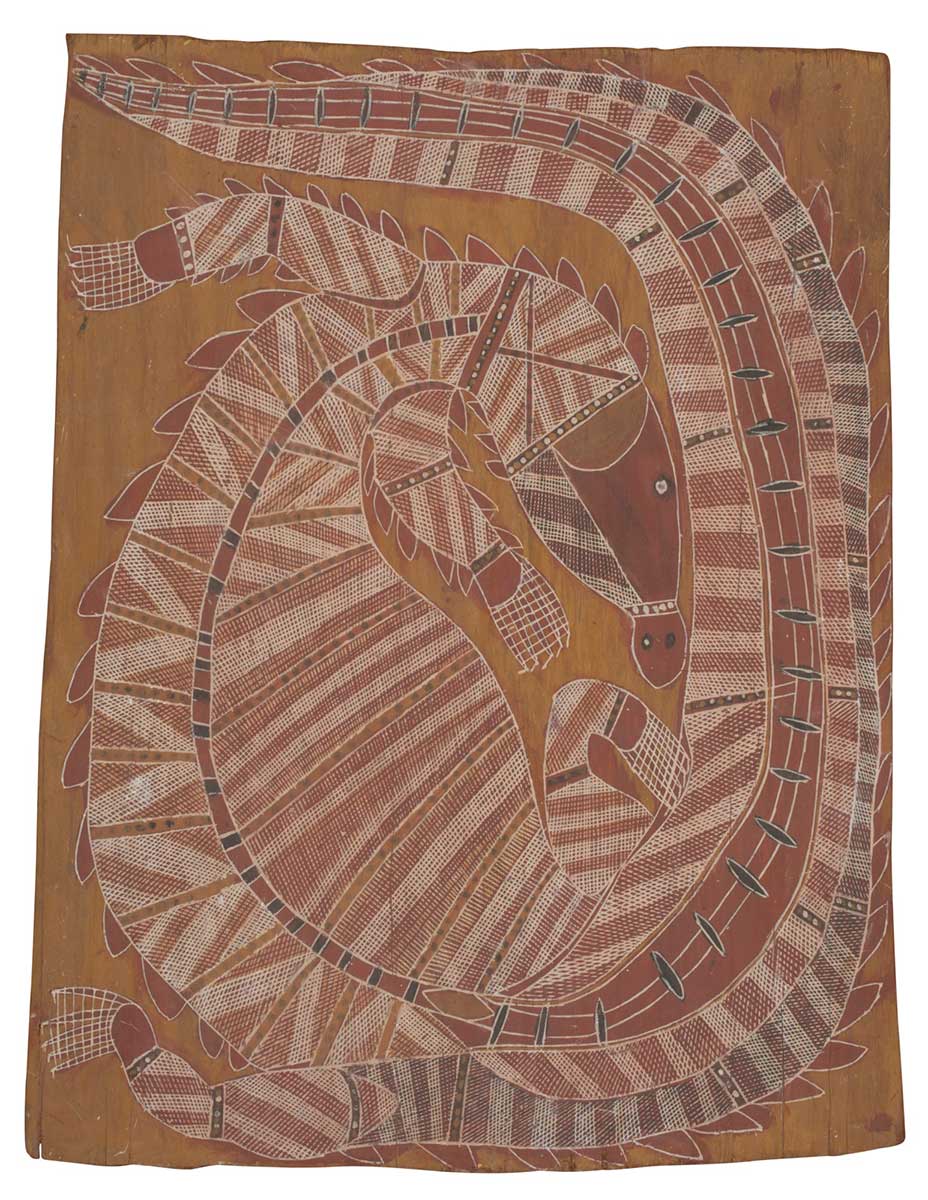

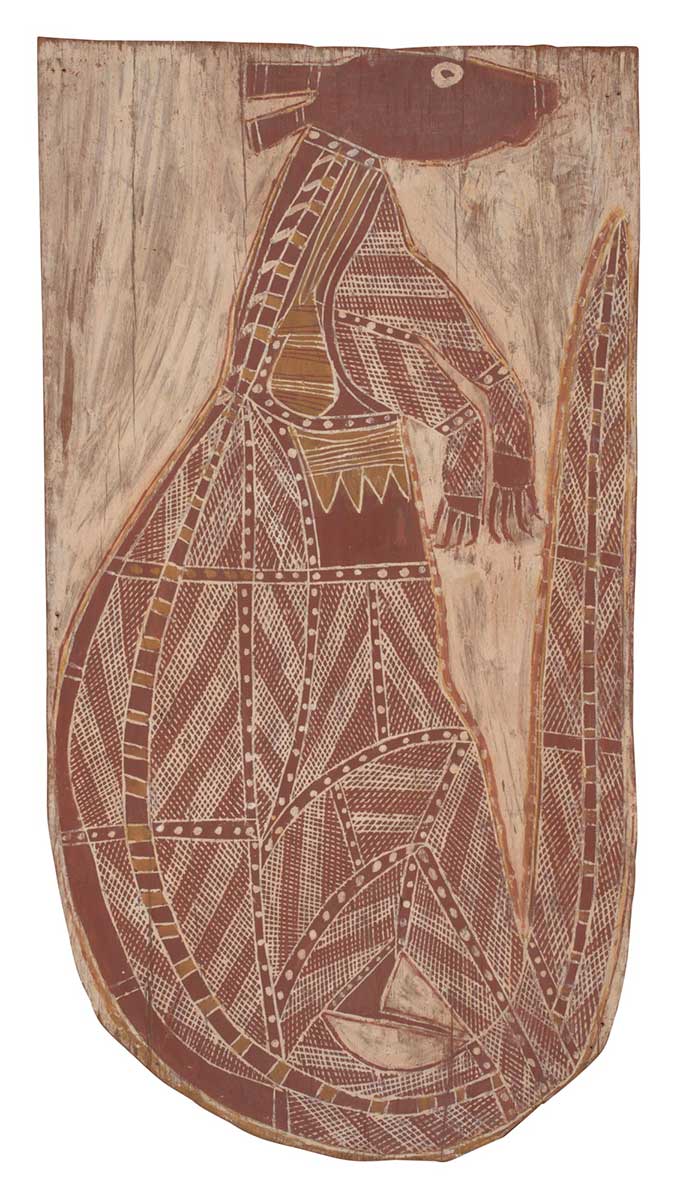

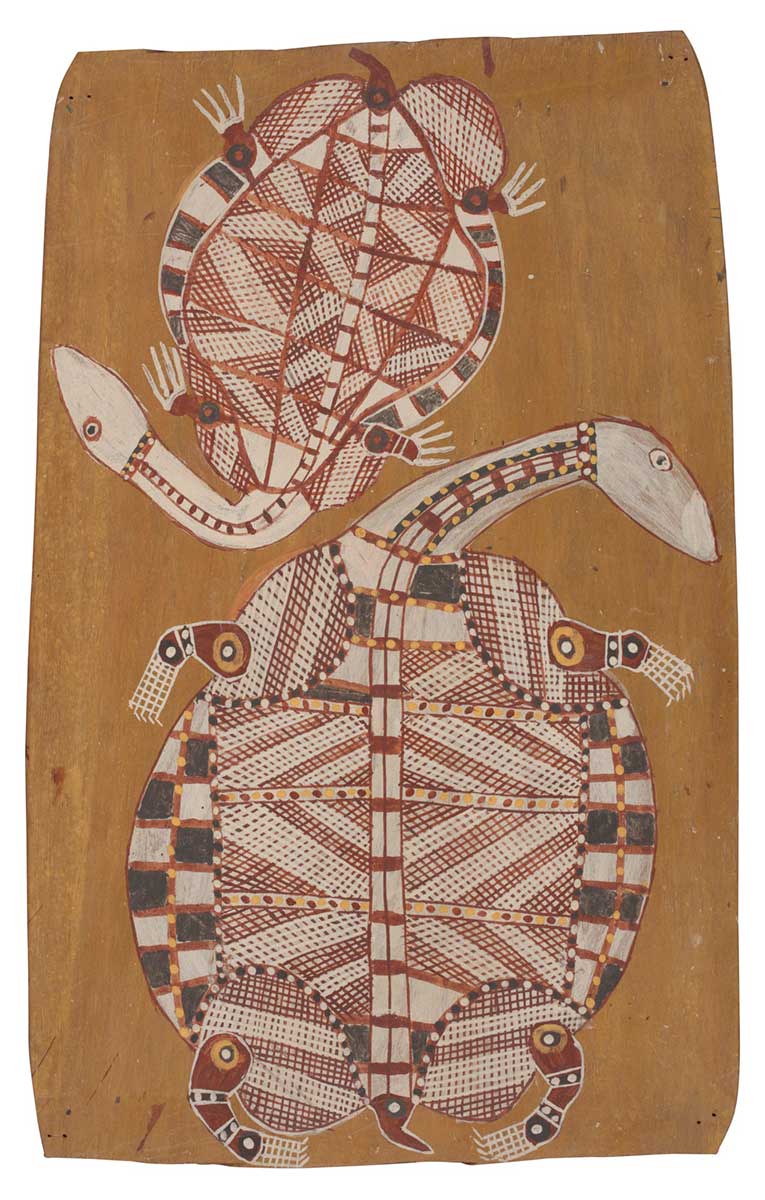

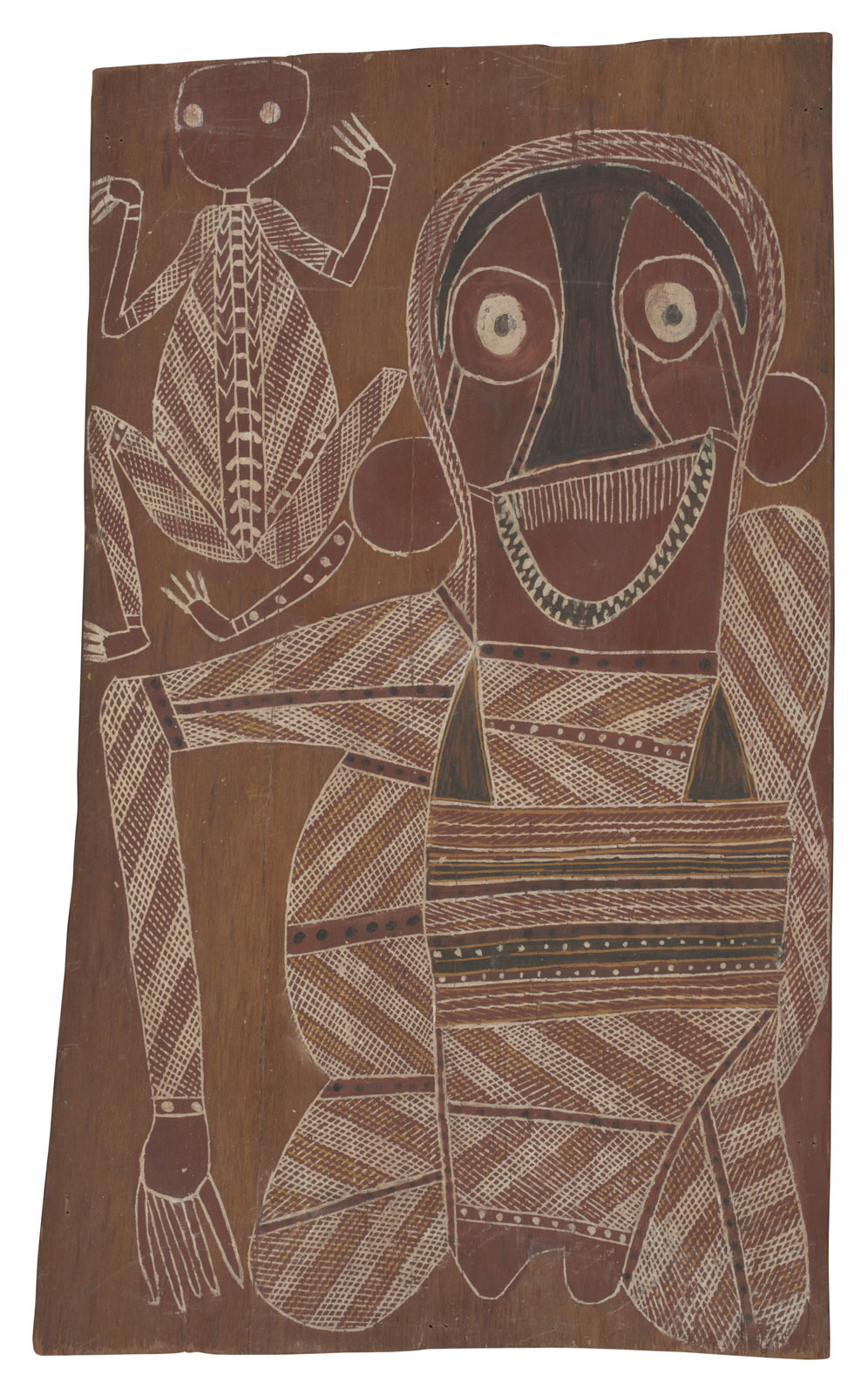

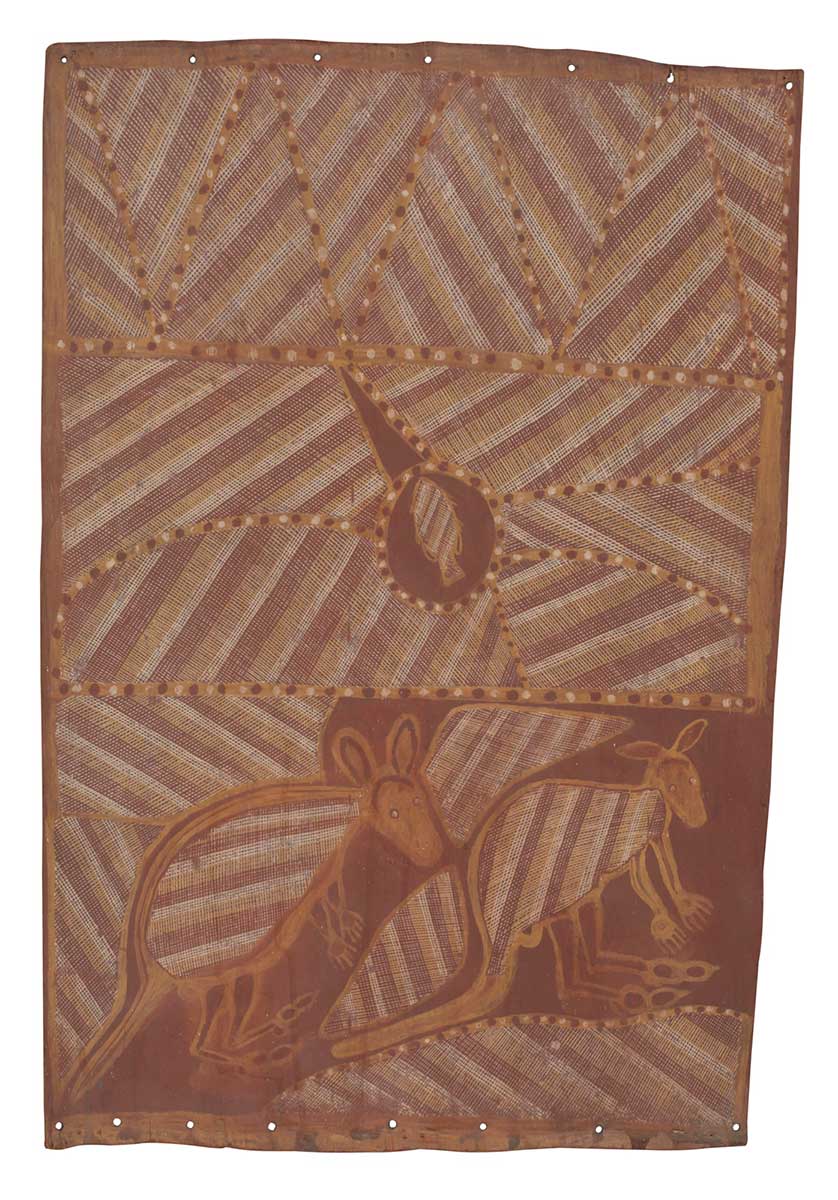

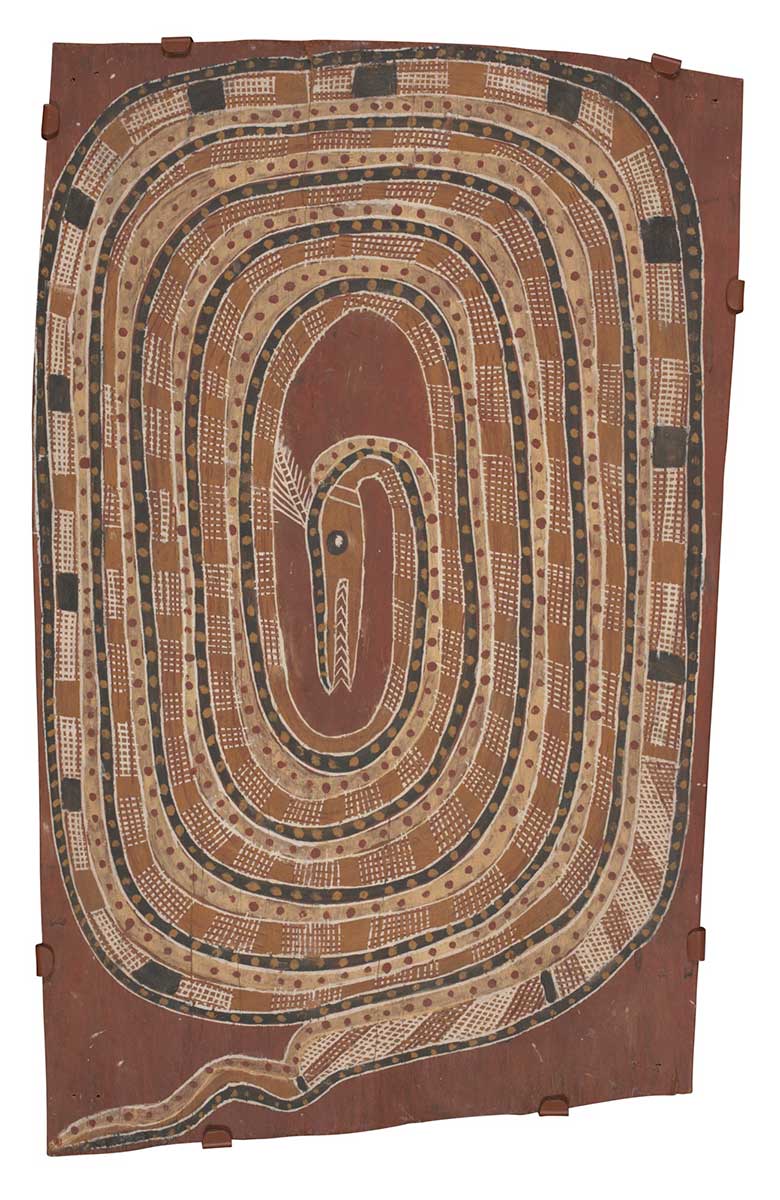

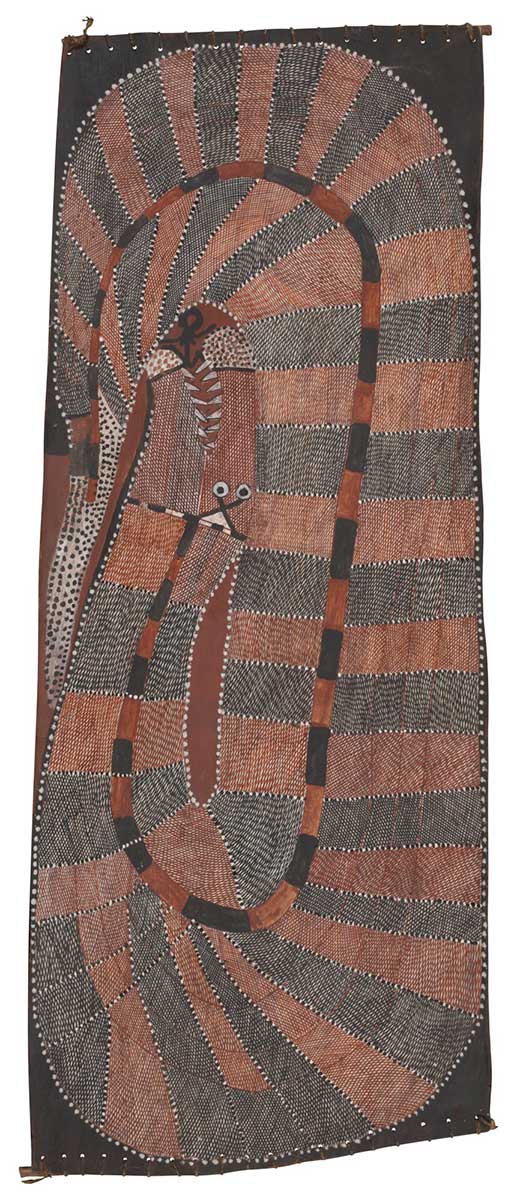

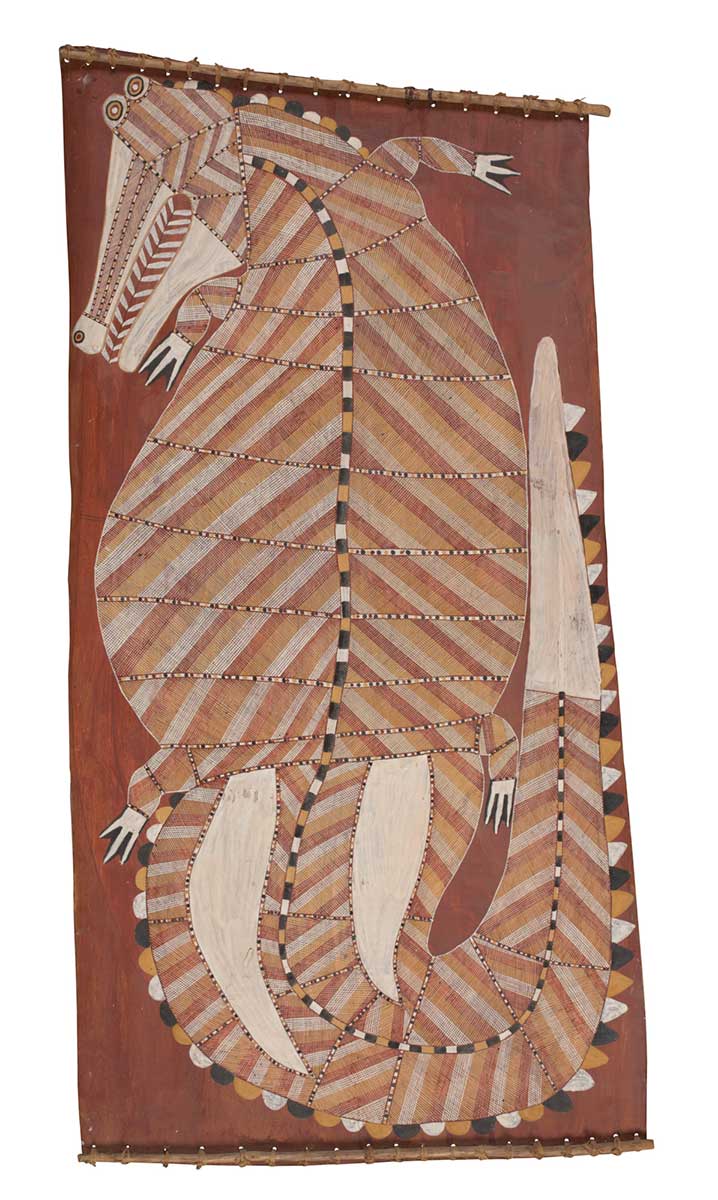

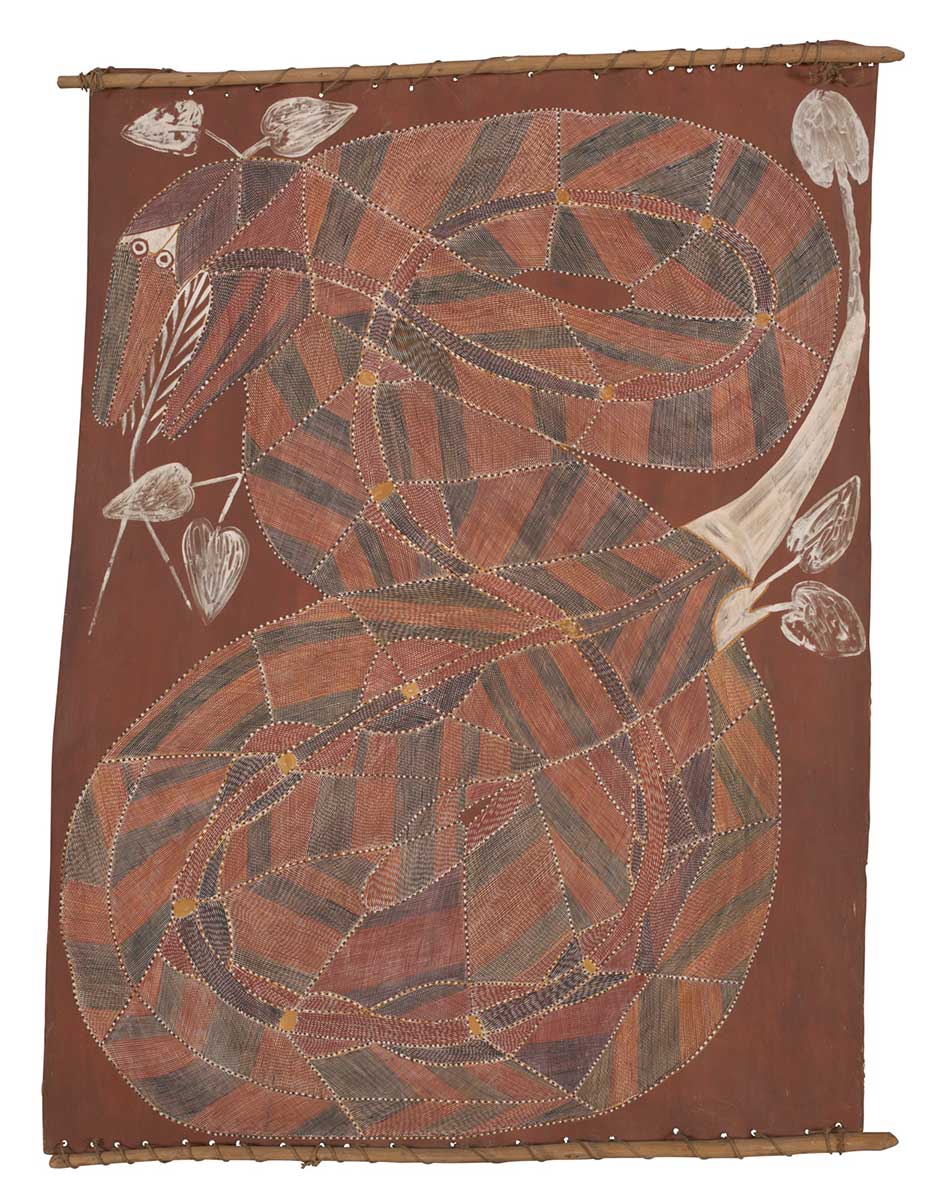

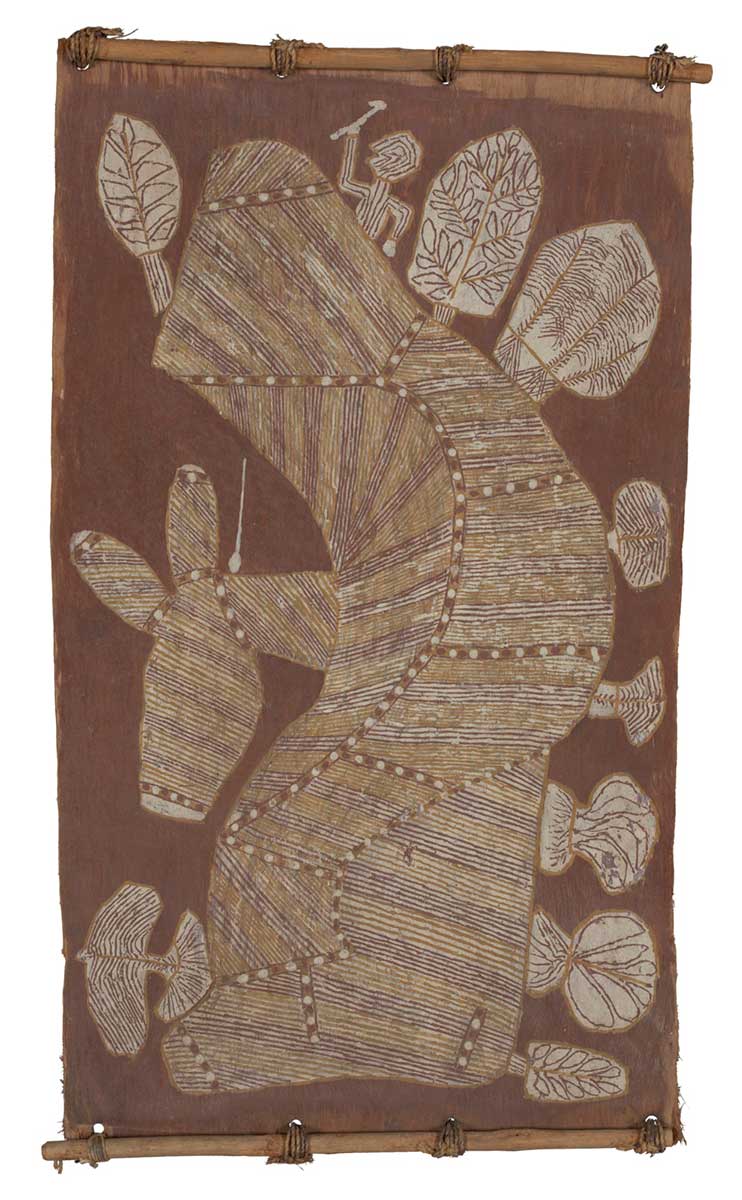

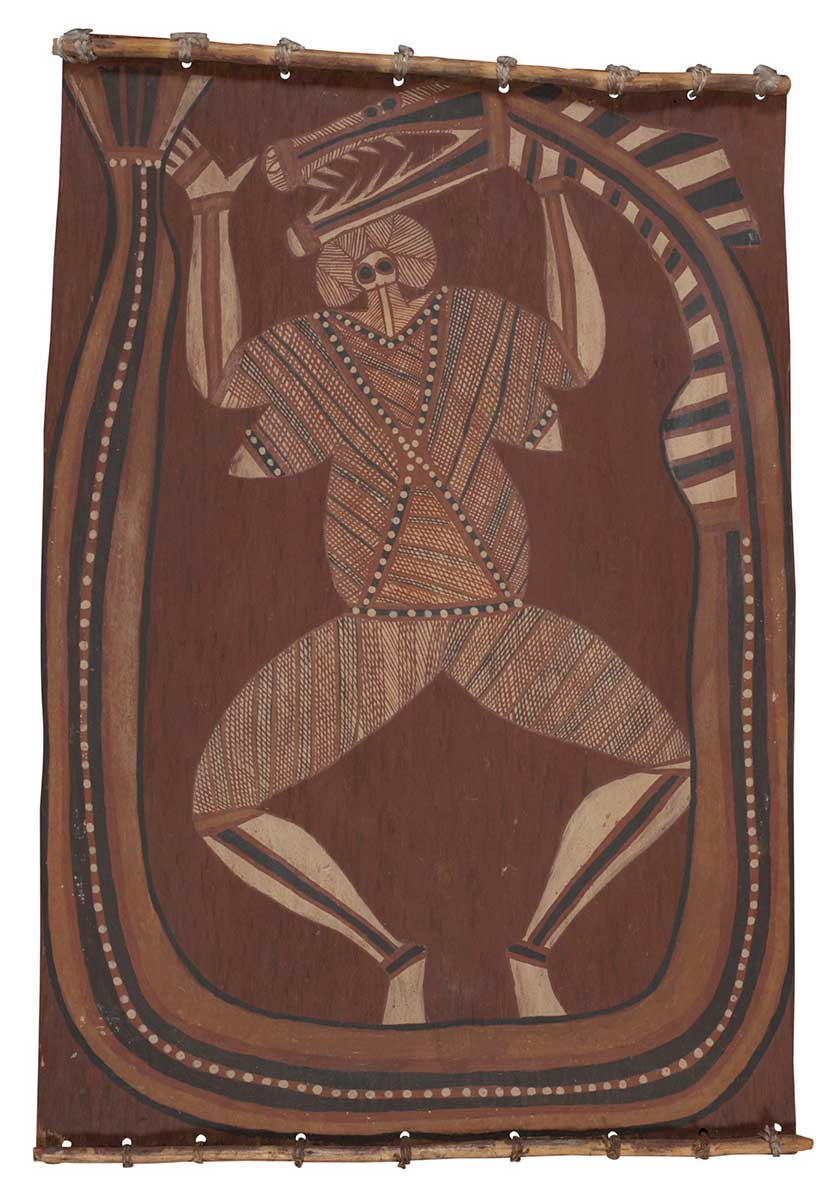

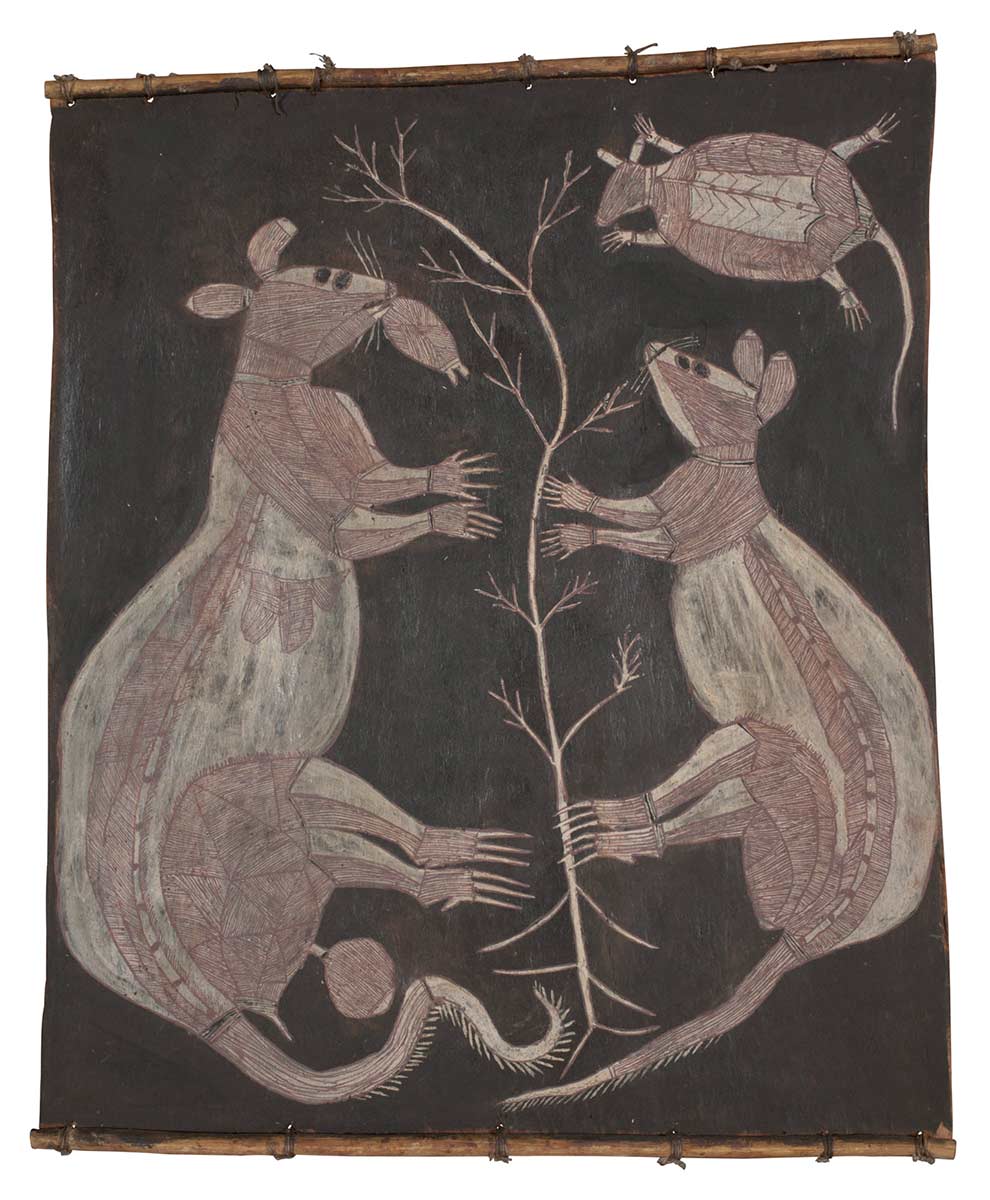

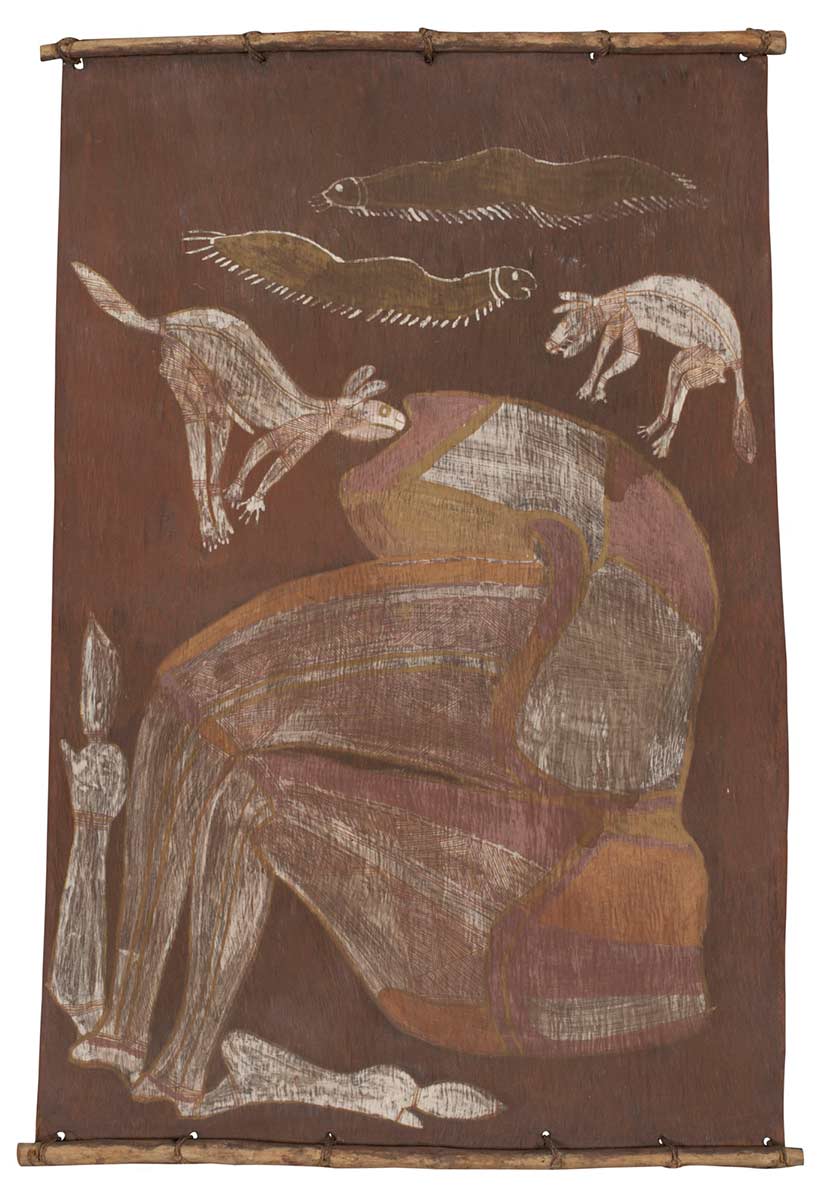

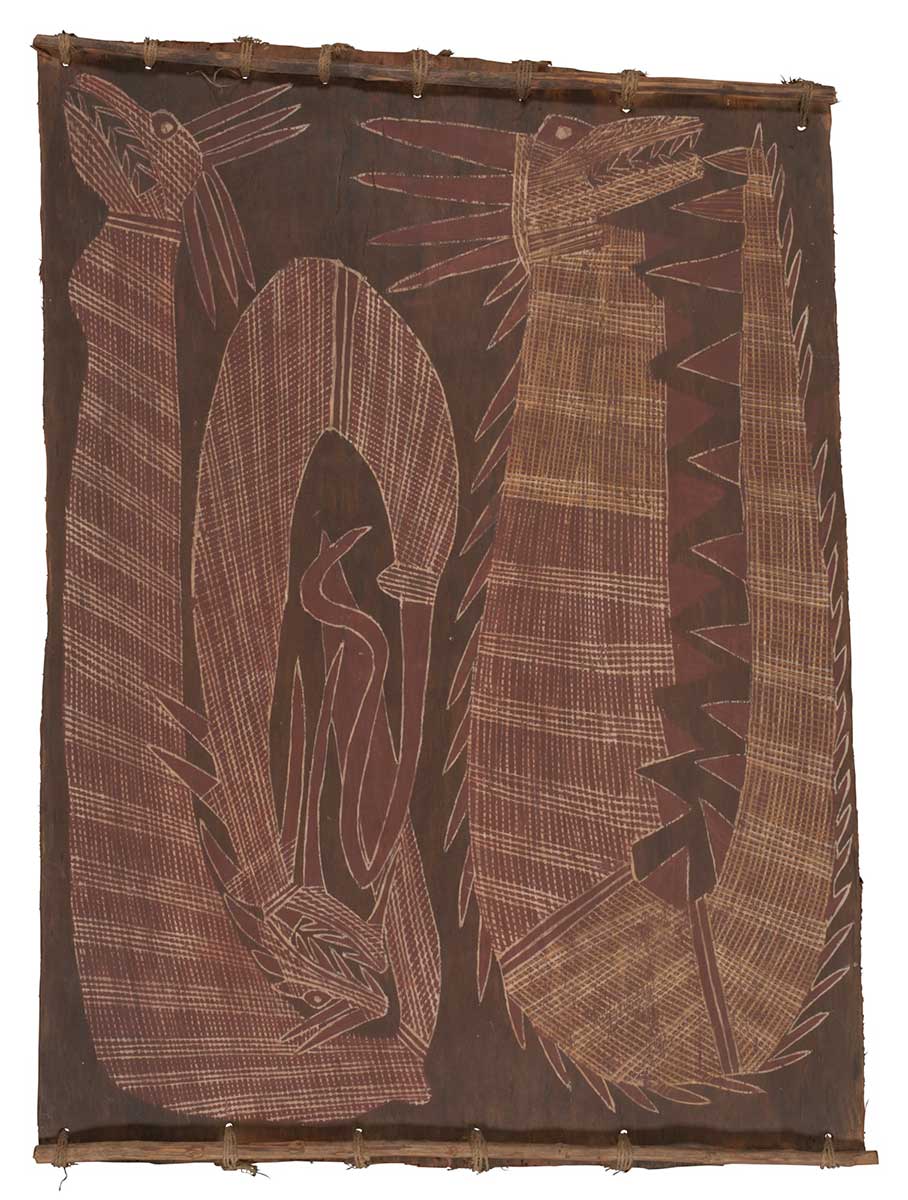

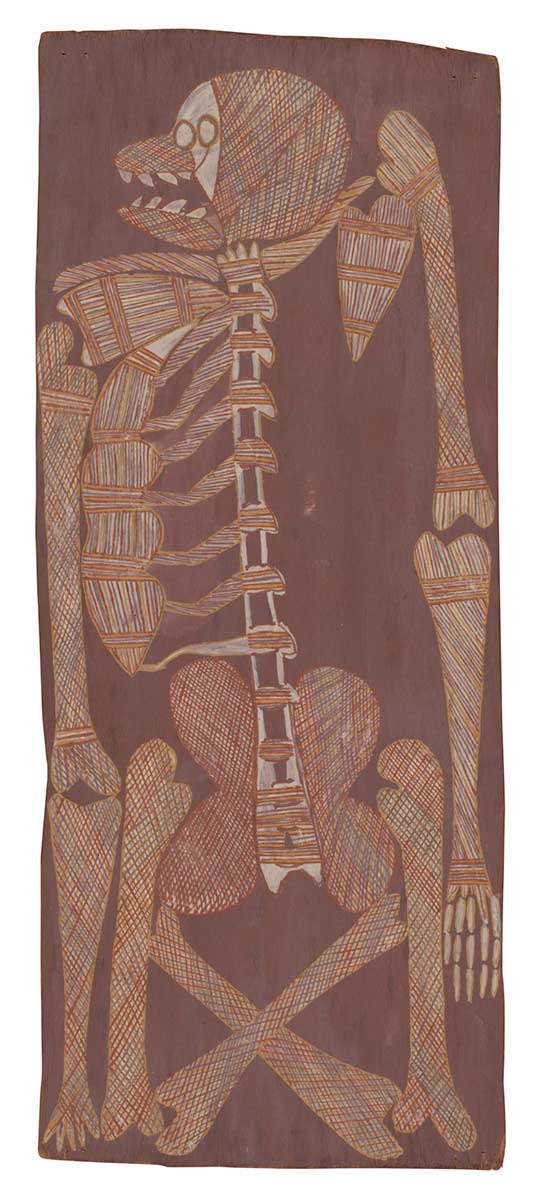

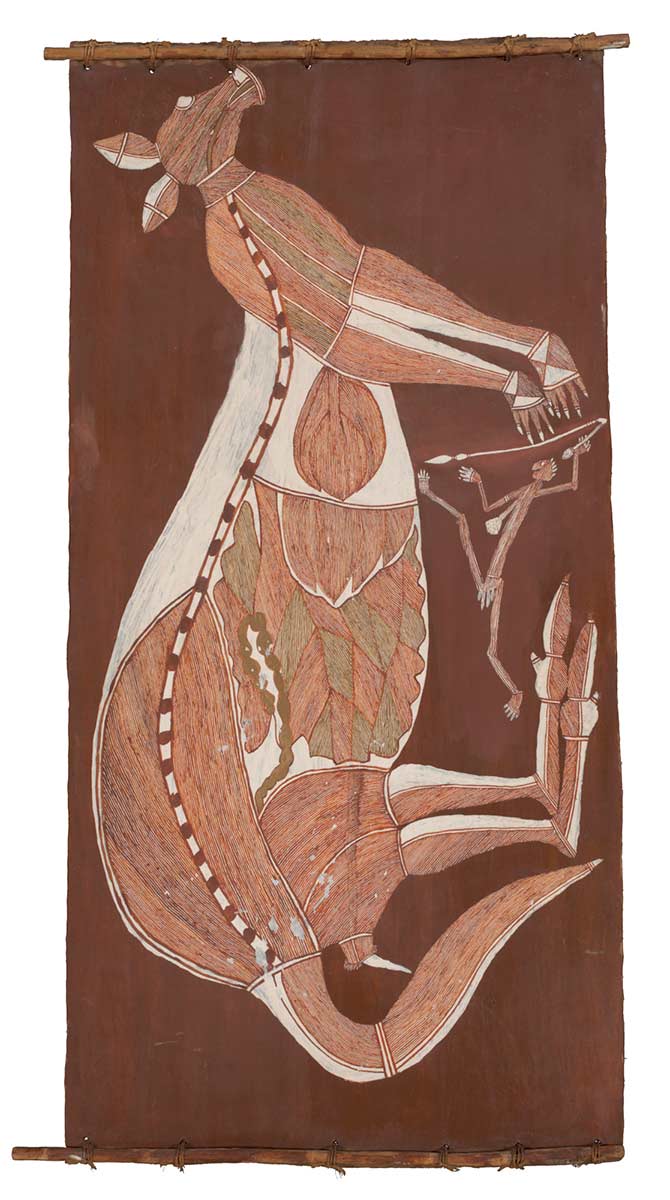

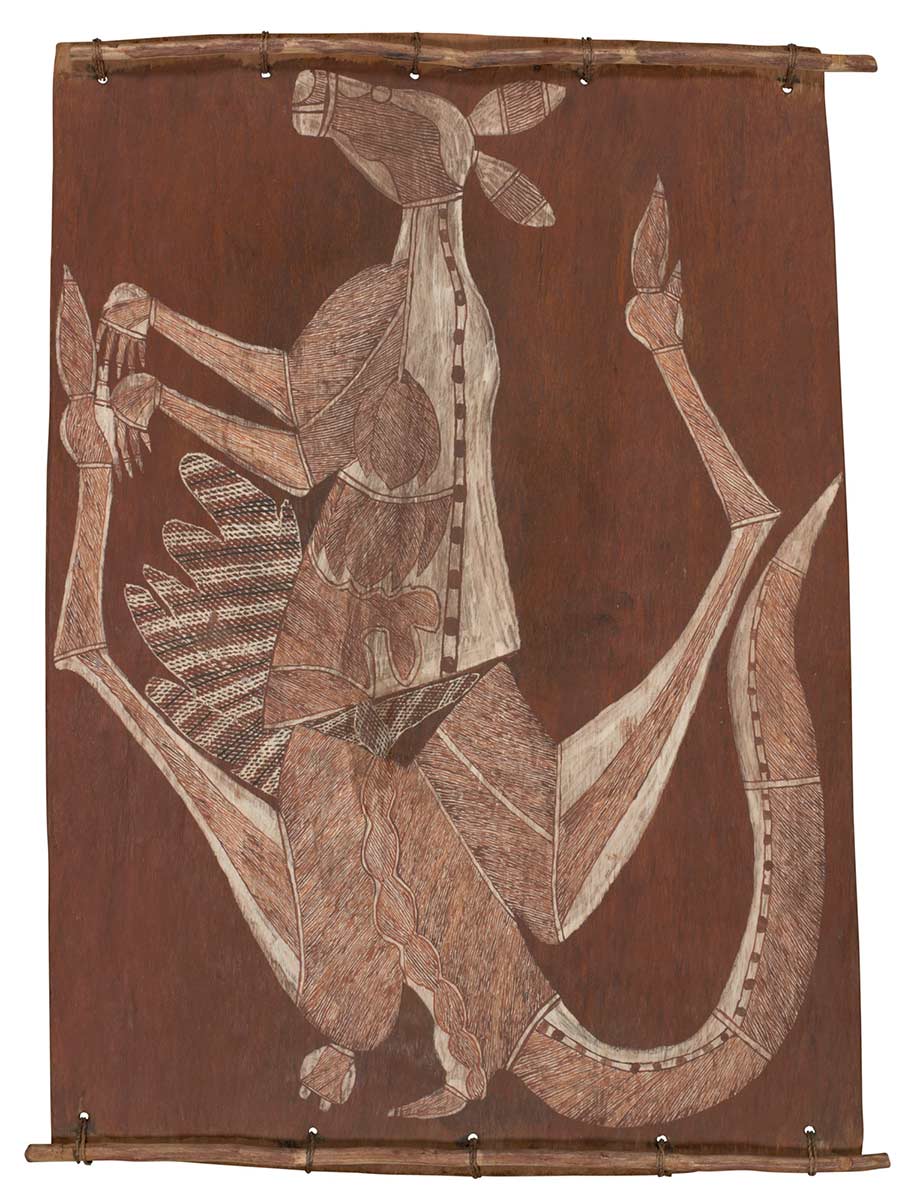

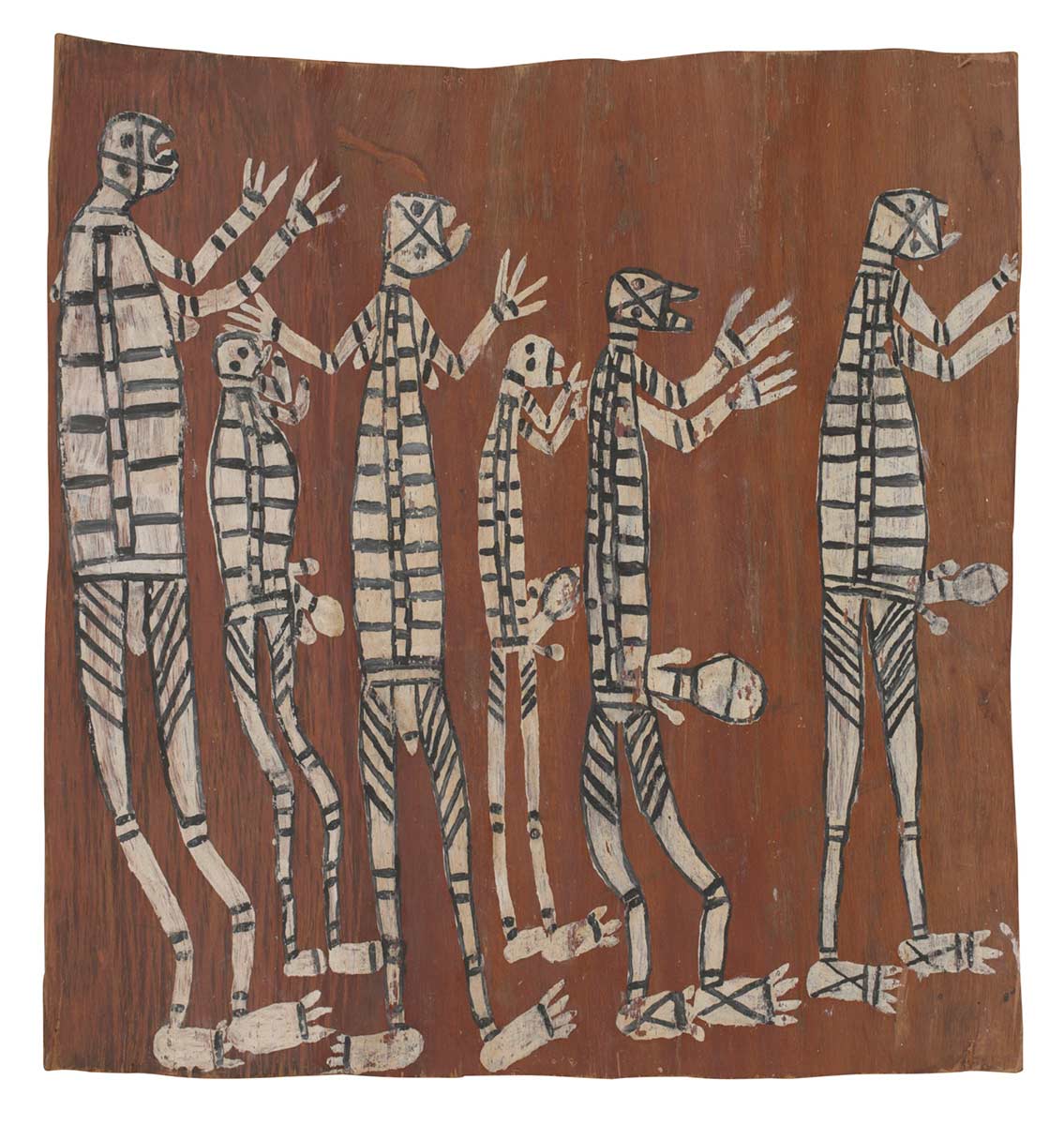

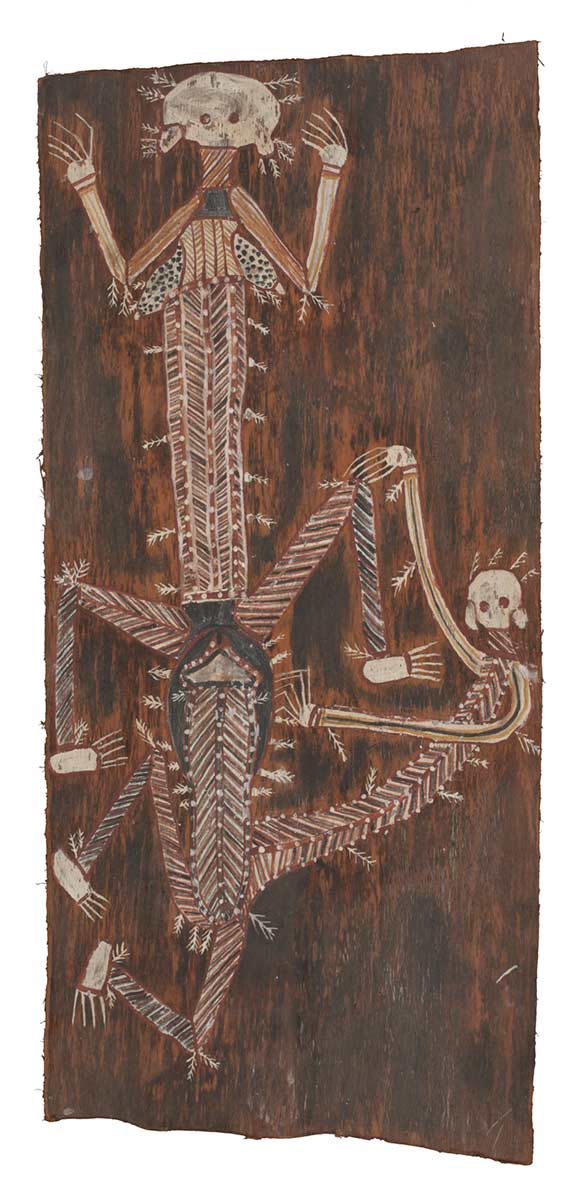

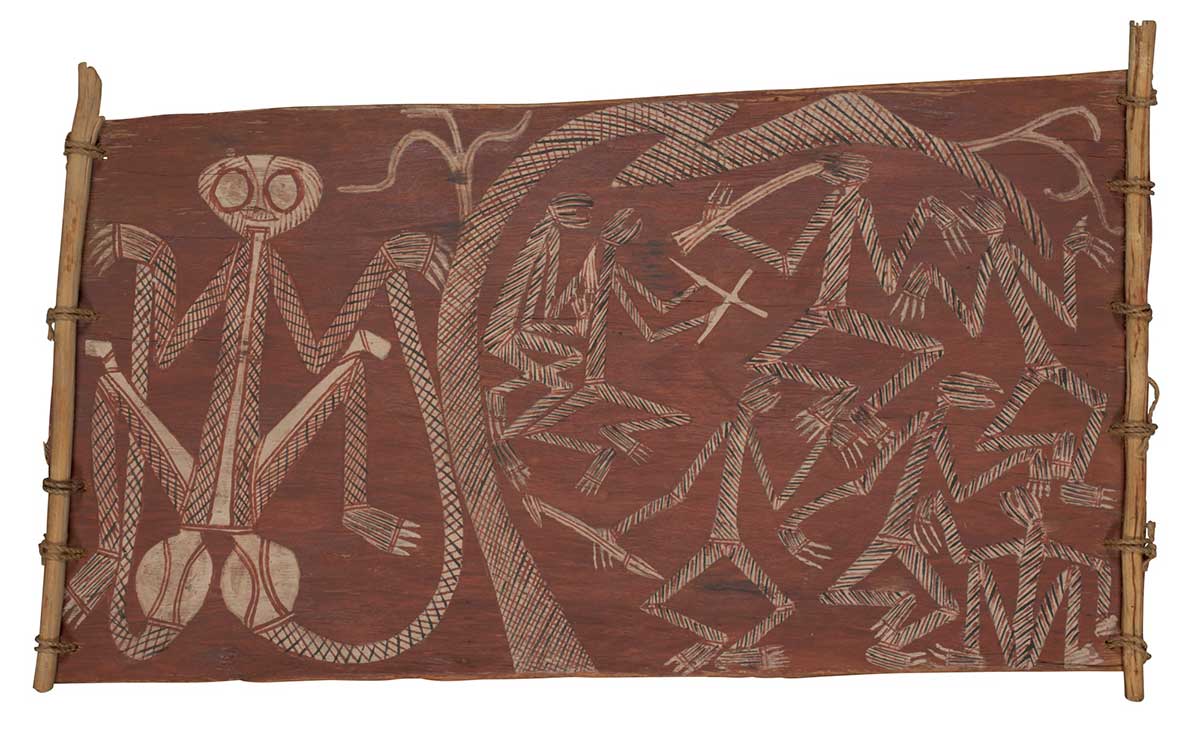

Themes represented in the paintings here include: Ngalyod the Rainbow Serpent, wearing a feather headdress to indicate its connection to ceremony; Lumaluma the Giant Ogre, whose limbs were cut off and transformed into ritual objects; Kandakidj the Antilopine Kangaroo associated with the Wubarr and Lorrkkon ceremonies; Namanjwarre the Estuarine Crocodile; and images of sorcery.

The school of Yirawala developed as a natural outcome of artists sharing camps and outstations with members of their extended families. Such places contain artists’ studios that are out in the open and surrounded by the daily activities of the family – rather than being locked away in secrecy. The open-air studios provide opportunities for artists to work together and to influence each other. They are also where younger family members learn about art.

Marrkolidjban outstation, in the Liverpool River region, played an important role in the history of the development of the artists tutored by Yirawala. It was here that Yirawala and Curly Bardkadubbu, both members of the Born clan, lived and worked in the early 1970s.

Bardkadubbu learnt from Yirawala to paint on bark and, around the same time, Yirawala taught his own sister’s son, Peter Marralwanga, the intricacies of painting patterns of rarrk. Marralwanga in turn taught his nephew Balang Nakurulk who, as a teenager, had been inspired by Yirawala.

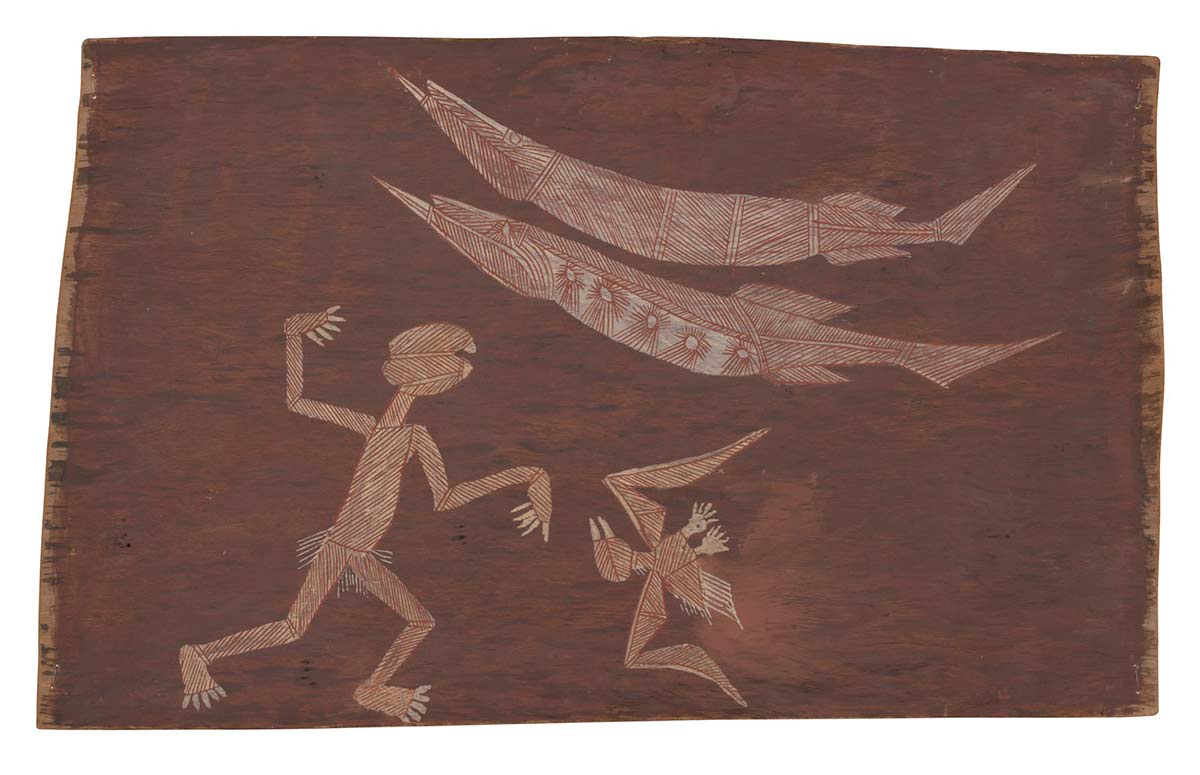

Note the similarities in these artists’ renditions of Ngalyod the Rainbow Serpent and Namanjwarre the Estuarine Crocodile. In each case the sheer power of the creatures is expressed in the drawing of the figures as coiled springs, ready to snap and unleash their herculean powers.

Figures in the landscape is a genre of painting in the western European tradition that seeks to express the connection between people and their environment, and its influence on a person’s identity. The ancestral figures in bark paintings not only inhabit the country, they also created it; they metamorphosed into its features and they deposited their ancestral forces within the earth itself.

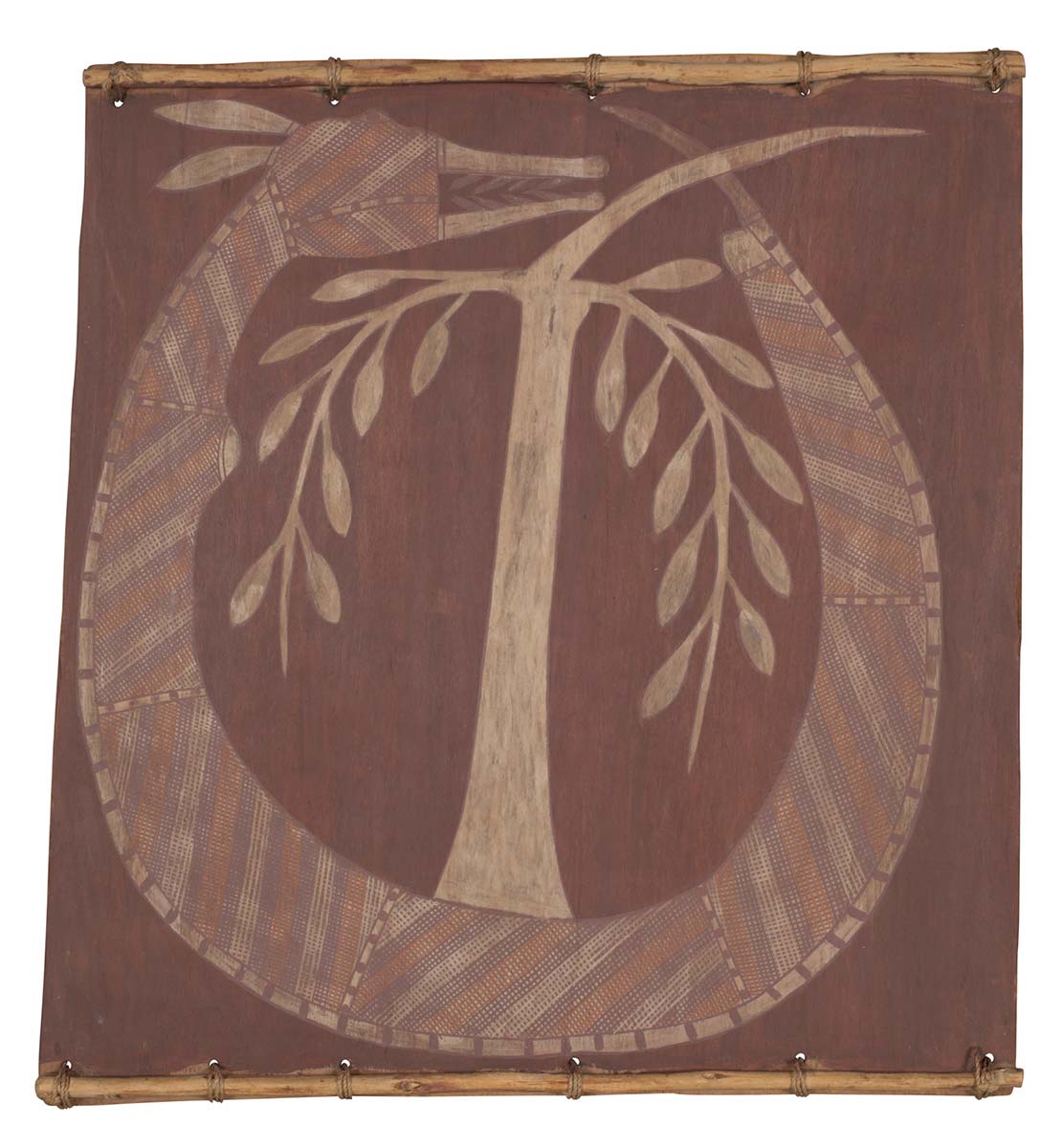

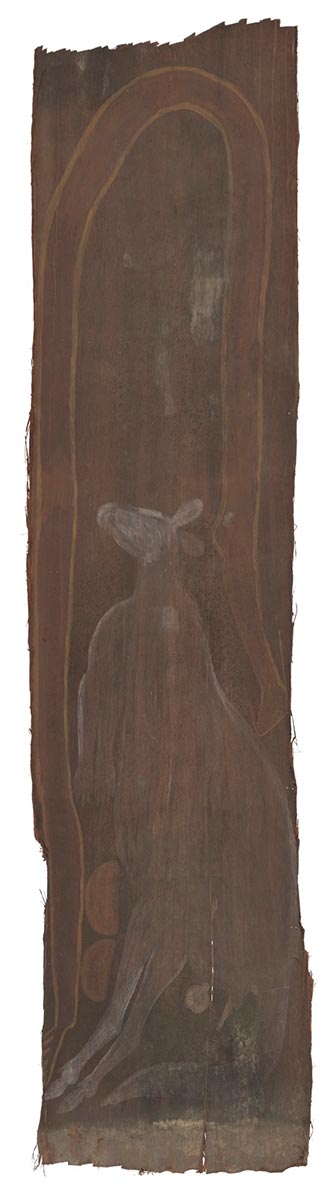

Chief among these creator beings is the Rainbow Serpent, commonly known as Ngalyod, who may appear in several guises. Ngalyod creates sacred sites by burrowing its way through the earth to emerge on the surface, where it encircles and swallows spirit beings. These may be taken into the ground or regurgitated as features of the landscape.

The Rainbow Serpent is sometimes drawn as a composite of several creatures, with the head of a crocodile or kangaroo, an emu’s crop and the tail of a fish. Ngalyod the Rainbow Serpent by Bardayal Nadjamerrek depicts Ngalyod beneath the surface of a billabong. Images of ‘seated’ beings indicate they are giving birth to particular sites.

The artists in this section all lived in and around the township of Oenpelli (Gunbalanya) in the 1960s and 1970s, when most of these paintings were made.

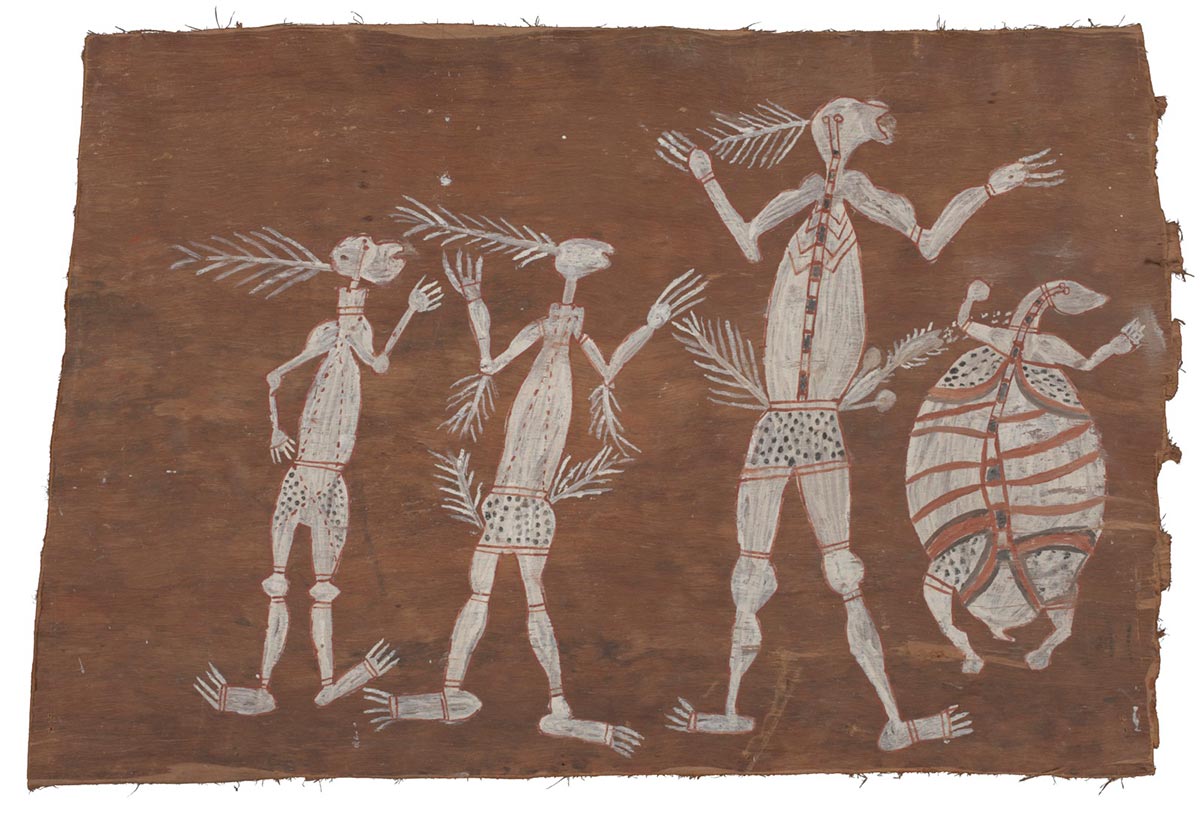

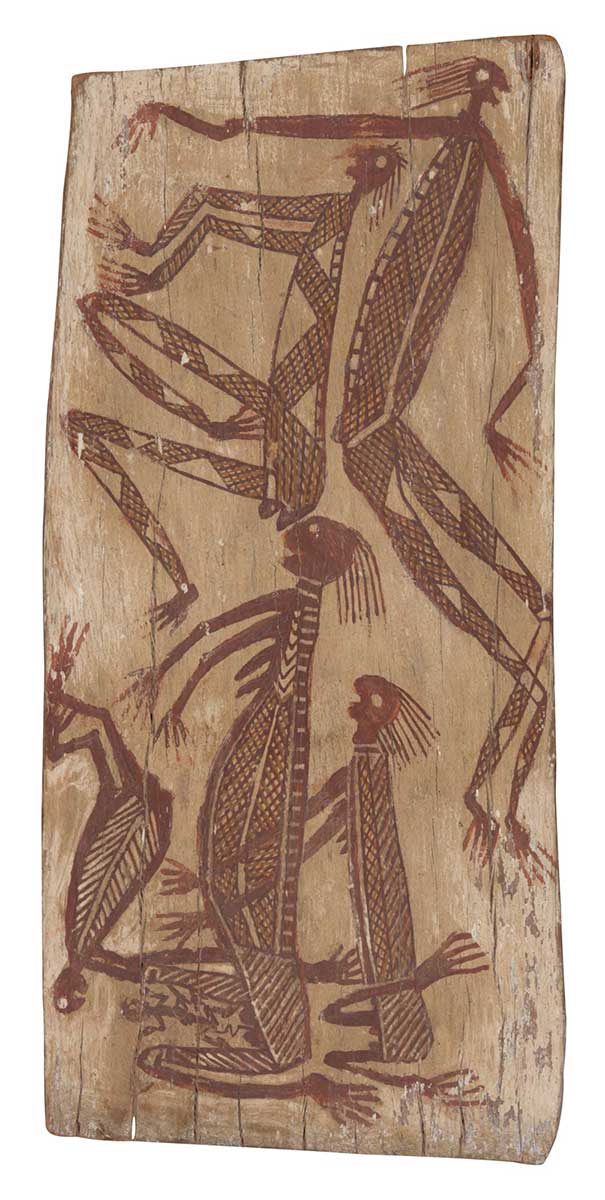

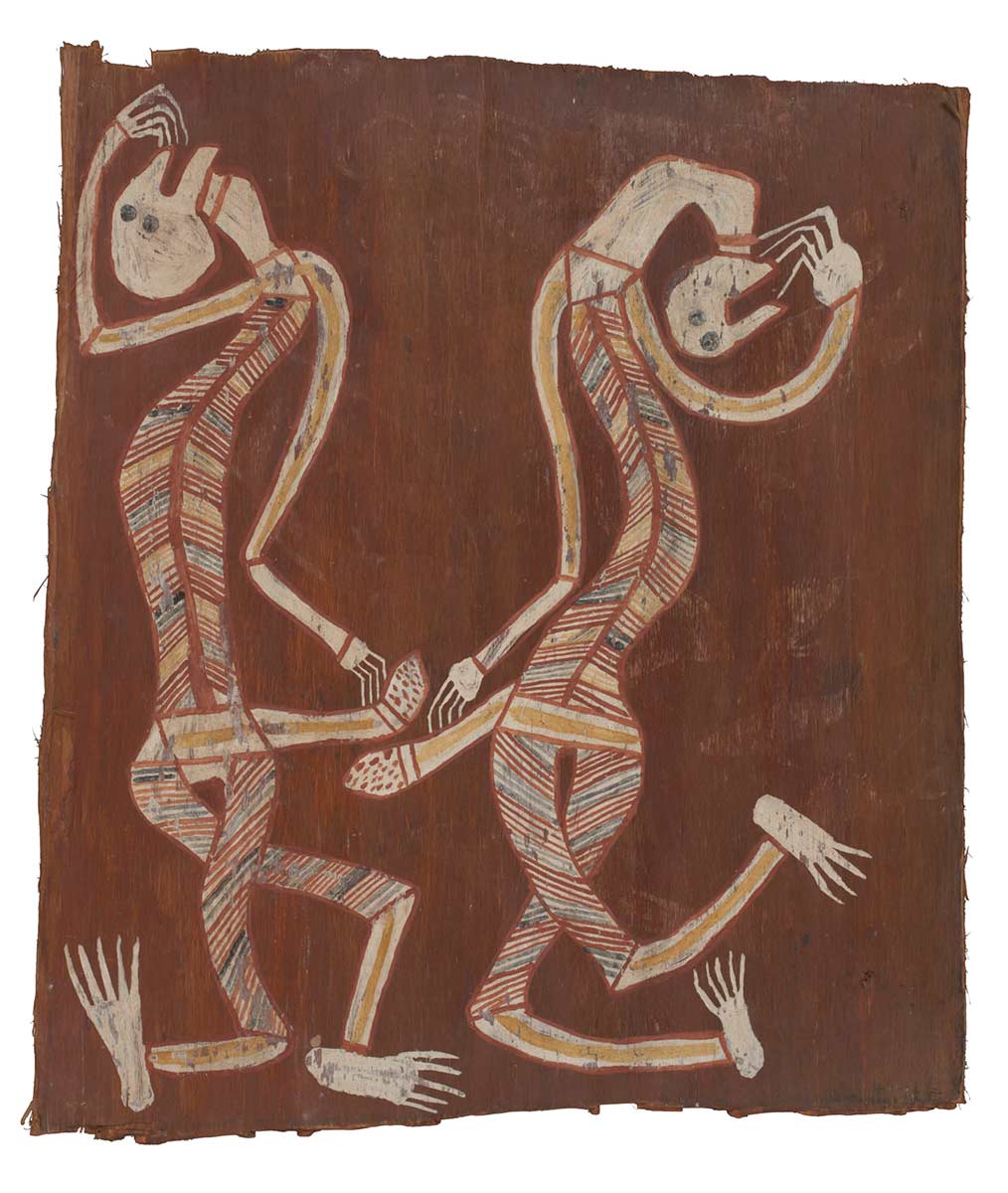

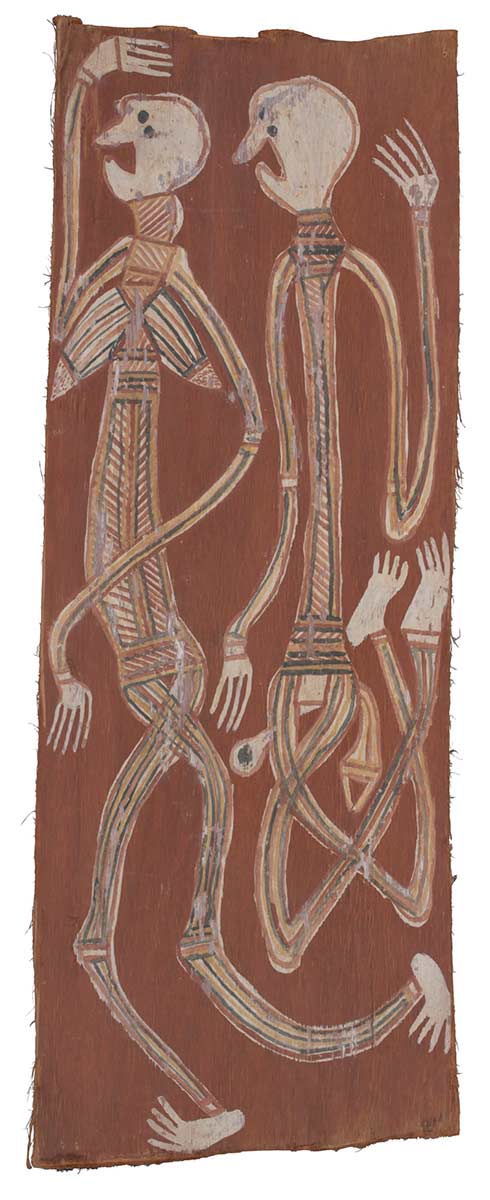

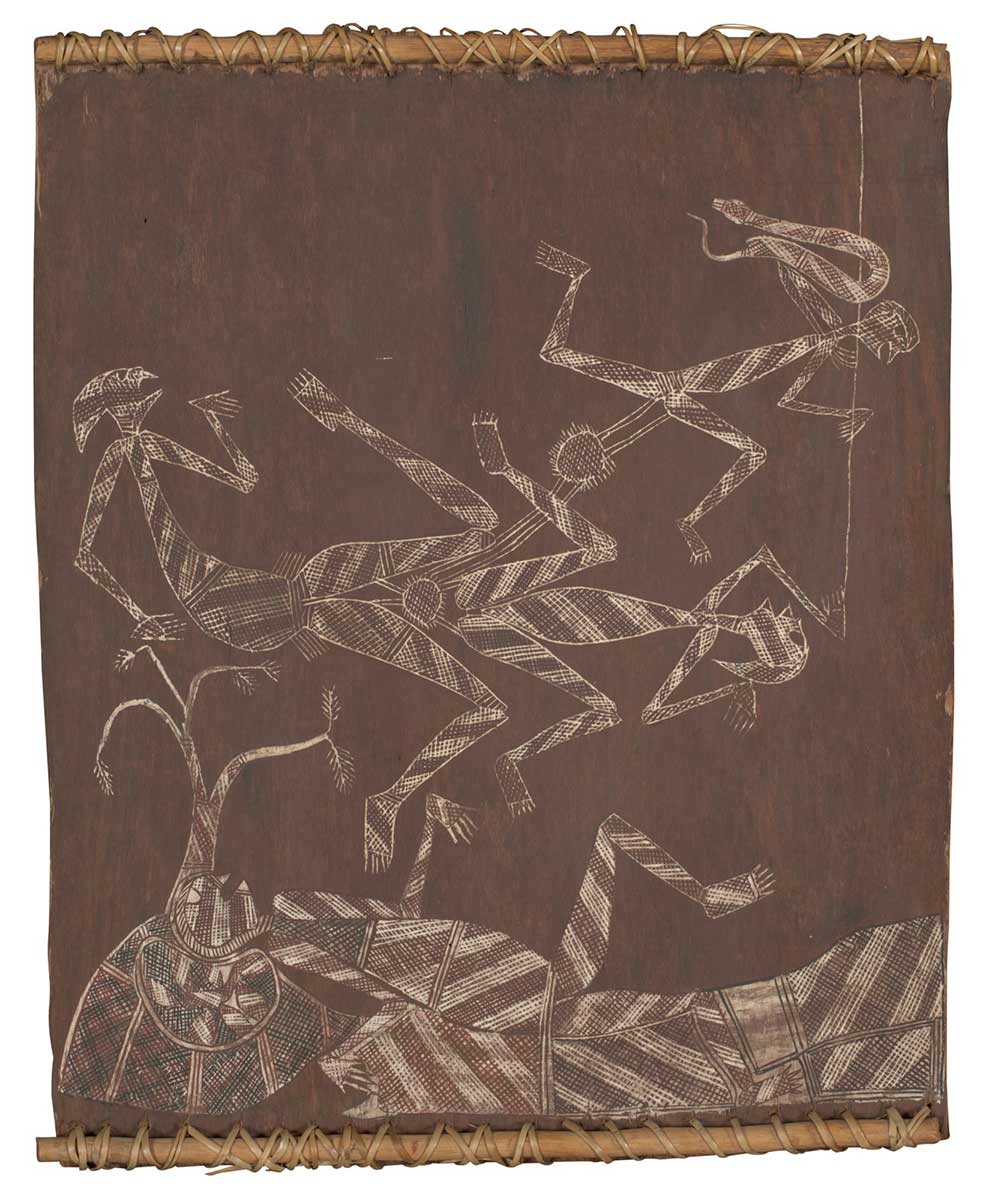

Dynamic figures is a term applied to a style of rock painting in western Arnhem Land that dates back at least 15,000 years. These figures are drawn as though caught in the act of movement, whether running, throwing a spear or dancing. A number of artists in this exhibition, including Najombolmi, Wally Mandarrk and Bardayal Nadjamerrek, also painted on rock.

The figures in these paintings are usually referred to as mimih. These are not ancestral or creator beings but spirits who inhabit the rocky escarpment. Mimih are credited with teaching the Bininj people the arts of living: how to hunt, cook, dance, sing and paint.

A type of painting that appears in the rock art of the region concerns sorcery. Such paintings were often commissioned to bring harm on a person who had wronged another, often for sexual infidelity. In the latter case, images of the culprits are drawn with distended and multiple limbs in awkward postures and occasionally with stingray barbs inserted into the joints and flesh to inflict pain.

The Nganjmirra family is one of the great artistic dynasties of Arnhem Land. Bobby Barrdjaray Nganjmirra was the senior artist of the group in the modern period. The family’s traditional lands lie to the east of Gunbalanya and are the focus of their paintings. Among the most important sites to the Nganjmirra family is Malworn, created by the Yawkyawk Sisters, Likkanaya and Marrayka; the latter is depicted in Barrdjaray’s painting of the same name.

The creation story of this site has similarities to that of the Wägilak Sisters in central Arnhem Land. Nimbuwah Rock is another important place to which the Nganjmirra family has custodial or managerial rights, as opposed to ownership, as it belongs to the opposite moiety, the Duwa.

Mural painting is another form of painting on bark, and stems from the practice of artists drawing or painting on the inside walls of their family bark huts or shelters.

There are two main types of bark shelter in Arnhem Land: one with straight walls, and the other made of walls curved over a horizontal beam (see George Milpurrurru’s Galawu (Stringybark House). Both types are built using large sheets of flattened bark. Painting on bark shelter walls predominated until the early 20th century, when collectors created a demand for more portable bark paintings.

Wally Mandarrk’s Borlung and Kangaroo was a mural made specifically for Mandarrk’s family in a camp at Mankorlod that was later abandoned. It was discovered by a Maningrida art centre manager, Dan Gillespie, in 1973. Two Frogs and a Baby Brolga was also cut from the wall of such a shelter.