By Wally Caruana, an independent curator, author and consultant specialising in Indigenous Australian art. For nearly 20 years he was the senior curator of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art collections at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

A short article in The Times of London on 17 August 1948 reported on the success of a scientific expedition to Arnhem Land and alluded to a number of rock paintings by Aboriginal ‘old masters’. [1]

Under the leadership of the anthropologist Charles P Mountford, the multi-disciplined expedition collected some 600 bark paintings and sculptures, which were later distributed to Australian state art galleries and museums, and to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. A number of these bark paintings are among the earliest works in Old Masters: Australia’s Great Bark Artists.

At the time these works were collected, anthropological interest in Aboriginal societies was growing and bark paintings were considered the quintessential form of Aboriginal art.

The first collections of bark paintings made on the basis of artistic and aesthetic merit, as opposed to ethnographic interest, were put together from 1912 by Walter Baldwin Spencer when he visited the buffalo hunting camp of Paddy Cahill at Oenpelli (now Gunbalanya) in western Arnhem Land. Spencer made several collections for the Museum of Victoria.

The artists

We know few of the names of the early painters that Spencer collected, but they would have included the fathers and uncles, brothers and cousins of a number of ‘old masters’ in this exhibition.

In this context, the term ‘old’ reflects two salient facts: these artists were born before the incursions of white settler society on their land and culture, and they carried one of the oldest continuing traditions of art known to humanity into a new era.

They experienced at firsthand the trauma of facing a foreign culture, one that was dominant and intending to settle.

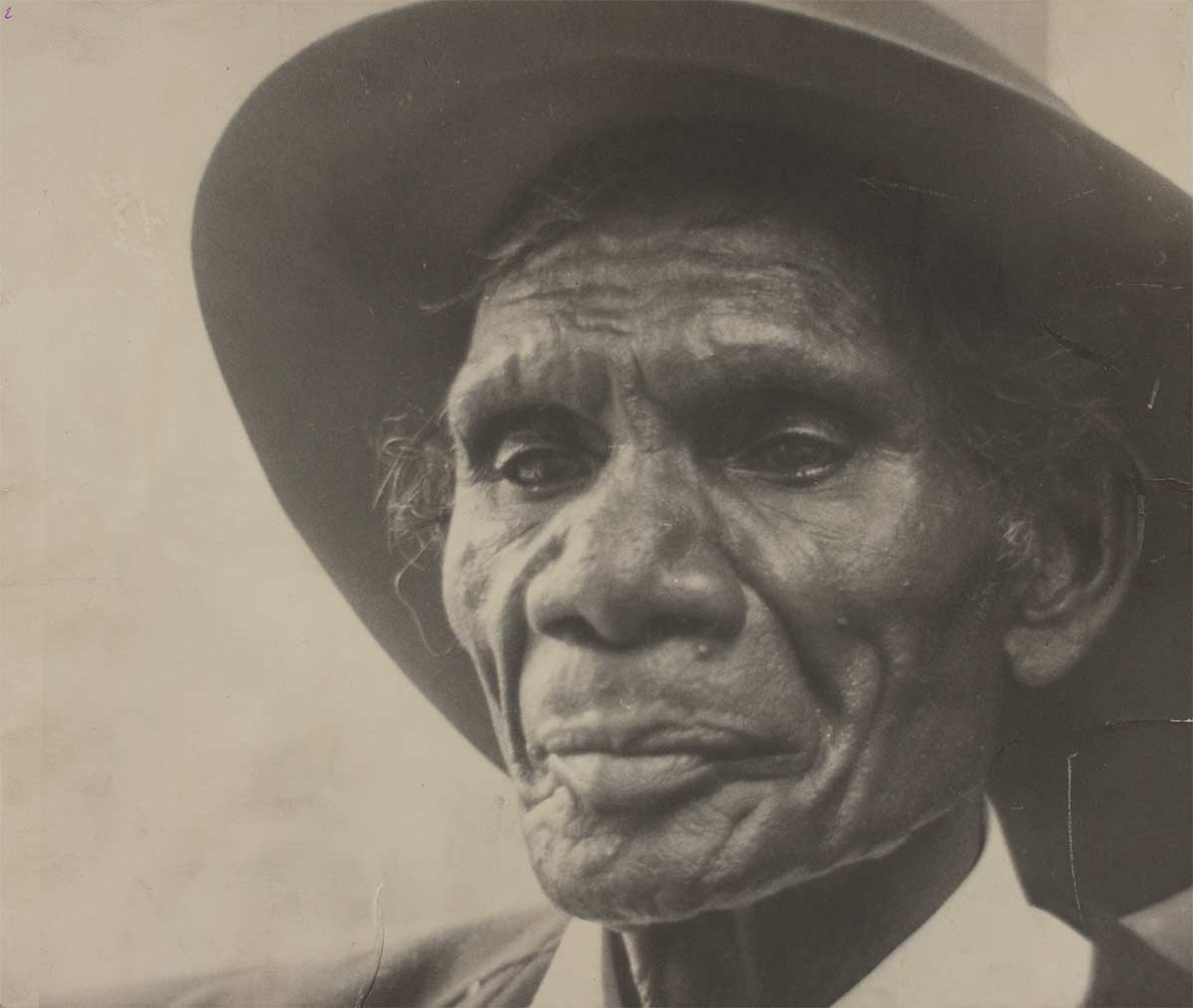

Yet senior men, such as Yirawala, Mawalan Marika, Muŋgurrawuy Yunupiŋu, Narritjin Maymuru and, in later years, Gawirrin Gumana and Jack Wunuwun, demonstrated their belief that art was an eloquent and effective means of bridging the gulf that separates the two cultures. Many of these men were ritual leaders, statesmen and cultural advocates as well as artists.

Yirawala, for one, painted so that balanda (non-Indigenous people) might appreciate the profound nature of Aboriginal culture and the essential bond that people have with the land.

Many painted for land rights and human rights: in 1963 the Yirrkala Church Panels, depicting the main ancestors of the Dhuwa and Yirritja moieties, stood on either side of the altar in the local mission church, reminding Yolŋu of their ancestral birthright; in the same year, the petitions on bark, which are surrounded by clan designs, proclaimed Yolŋu’s unique relationship with the land in the face of mining; and The Aboriginal Memorial (1988) stands as a testament to the Indigenous lives lost while defending their lands since 1788.[2]

A number of the artists in this exhibition were prominent contributors to these watershed moments in the history of Arnhem Land art and in the developing relationship between Aboriginal people and balanda.

In an effort to appreciate the magnitude of the artistic achievements of these men, curators and art historians have resorted to comparisons with the elite of Western European art: Yirawala has been known as the ‘Picasso of Arnhem Land’,[3] and Jack Wunuwun, the ‘Michelangelo’.[4]

Indeed, Yirawala along with Narritjin Maymuru form the backbone of this exhibition. In their time, both these men were at the forefront of the social and cultural struggles experienced by Indigenous Australians, and were supremely gifted, innovative and influential artists whose legacies continue to this day.

Styles and techniques of painting

Broadly speaking, the art of bark painting is based on a series of unique but related visual languages. In western Arnhem Land, the connection to rock art has resulted in the predominance of figurative imagery, reliant on the artist’s draughtsmanship.

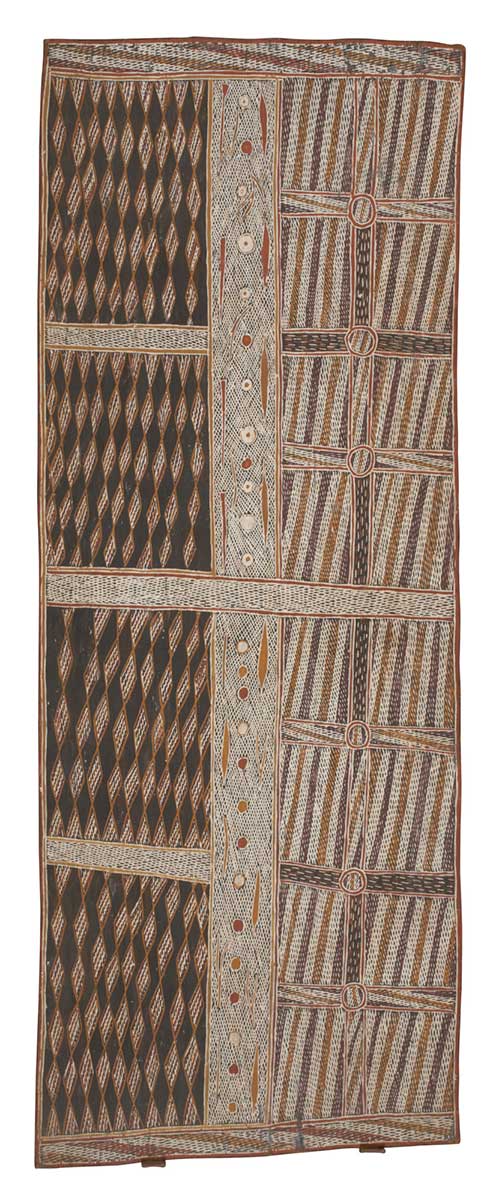

In eastern Arnhem Land, bark painters prefer geometric compositional templates with an emphasis on patterned clan designs.

In central Arnhem Land, artists tend to combine both approaches. In fact, figurative, abstracted or geometric imagery exists in all areas.

Arnhem Land paintings are characterised by the use of fine crosshatched patterns of clan designs that carry ancestral power: the crosshatched patterns, known as rarrk in the west and miny’tji in the east, produce an optical brilliance reflecting the presence of ancestral forces.

These patterns are composed of layers of fine lines, laid onto the surface of the bark using a short-handled brush of human hair, just as they are painted onto the body for ceremony.

The artist’s palette consists of red and yellow ochres of varying intensity and hues, from flat to lustrous, as well as charcoal and white clay. Pigments that were once mixed with egg yolk or orchid juice as a binder have, since the 1960s, been combined with water-soluble wood glues. Nonetheless, some artists, such as Wally Mandarrk, insist on using traditional binders.

The bark, the artist’s canvas, is stripped from Eucalyptus tetrodonta (stringybark) during the wet season, then cured over fire and flattened under weights.

Physical environment

The physical environment of Arnhem Land is diverse. In the west the rocky escarpment that extends into Kakadu National Park is home to hundreds of rock overhangs, shelters and caves bearing paintings – veritable ‘cathedrals of art’ – that date back 30 millennia. The practice of rock painting continues to this day, and Najombolmi, Bardayal Nadjemerrek and Wally Mandarrk are among a number of rock painters represented in this exhibition.

To the east, across to the Goyder and Glyde rivers, lie the savannah forests and the Arafura Wetlands of central Arnhem Land. In 1993 the pristine wilderness of the wetlands gained environmental protection through World Heritage Listing based on its unique ecology and its cultural value to the Ganalbiŋu and related groups in the area.

From here, chains of islands lead to the eastern coast of Arnhem Land and south to Blue Mud Bay, where the full metaphorical and physical forces of fresh water meeting salt water are evident in the landscape and out to sea, and are played out on bark.

Societies

Despite the variety of languages and dialects spoken across Arnhem Land, clans in the region share much in the way of connections to ancestors, belief systems, ritual practices, exchange ceremonies and social structures.

The peoples of the west are known by the collective term Bininj, while those in central and eastern regions refer to themselves as Yolŋu. The exhibition follows this distinction, with the main artists, Yirawala and Narritjin, belonging to the Bininj and Yolŋu groups respectively.

Arnhem Land societies are complex in their structures, but fundamentally they are divided into two halves, known by the word ‘moiety’, an anthropological term derived from the French moitié (half). In eastern and central Arnhem Land the moieties are called Dhuwa and Yirritja, and Duwa and Yirridjdja in the west.

Every person, clan and animate or inanimate thing – whether an ancestor, animal, feature of the landscape or natural phenomenon – belongs to one moiety or the other. Ownership of land, ceremonies and painted designs is inherited from one’s father, while custodial or managerial rights are inherited from one’s mother.

A person must marry someone of the opposite moiety, and people belonging to each moiety play different but complementary roles in ceremonies.

A number of sections in Old Masters have been organised according to the artists’ or subject’s moiety affiliation, and the introductory work, The Djan’kawu Cross Back to the Mainland (right), by Djunmal, features designs belonging to both moieties.

Missions and townships

In 1931 the Australian Government declared Arnhem Land an Aboriginal reserve. This was an era when it was believed the Aboriginal race was inferior and would soon disappear. All the bureaucracy could hope to do was ‘smooth the pillow of a dying race’.[5]

Mission stations had been set up across the region: from Paddy Cahill’s buffalo hunting camp at Oenpelli, which became a mission in 1916, to the missions established at Milingimbi in 1923, Yirrkala in 1935, Minjilang (Croker Island) in 1940, and Galiwin’ku (Elcho Island) in 1942. Maningrida was set up as a trading post in 1947, and the township of Ramingining was built in the early 1970s.

With the introduction of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act in 1976, there was a movement away from these main townships. Today, many people live in smaller communities on their traditional lands, which are referred to as homelands or outstations.

The collectors

Mountford’s 1948 expedition to Arnhem Land visited Oenpelli, Yirrkala and Groote Eylandt.[6] The National Museum of Australia’s vast holdings of bark paintings from Arnhem Land include substantial numbers of works that were gathered by the collectors who came after Mountford. Dorothy Bennett accompanied Tony Tuckson and Stuart Scougall in the late 1950s on their pioneering collecting trips on behalf of the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Bennett struck out on her own and, as with all of these collectors, forged close links with the artists, especially around Oenpelli and Minjilang. Karel Kupka, the Czech–French artist and ethnographer, first visited Australia in 1951 with the express purpose of collecting on behalf of European museums. He was one of the first to describe bark paintings in artistic and aesthetic terms.[7]

In fact, anthropologists and ethnographers were the first to record the ‘art history’ of Aboriginal art. Helen Groger-Wurm, an Austrian scholar who collected on behalf of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies,[8] was privileged by the trust that Yolŋu artists placed in her,[9] and Sandra Le Brun Holmes became the patron of Yirawala.[10]

JA (Jim) Davidson, a passionate supporter of the art and artists of Arnhem Land, became a close friend of Mathaman Marika, among others.[11] These are some of the collectors whose efforts, enthusiasm and passion created the great collections from which the Old Masters exhibition is drawn.

Notes

1 Anonymous, ‘Rich finds of Arnhem Land Expedition’, The Times, 17 August 1948, p. 3.

2 The Aboriginal Memorial (1988) now stands at the entrance to the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

3 Yirawala: Picasso of Arnhem Land is the title of a film by Sandra Le Brun Holmes (Morning Star Productions, Sydney, 1982)

4 James Mollison, the founding director of the National Gallery of Australia, quoted in P Ward, ‘The Michelangelo of Arnhem Land’, The Australian, 12–13 September 1987, supplement, p. 3.

5 A phrase that was first used by anthropologist Daisy Bates in her memoir, The Passing of the Aborigines: A Lifetime Spent Among the Natives of Australia, Murray, London, 1938.

6 CP Mountford (ed.), Records of the American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land, vol. 1: Art, Myth and Symbolism, Melbourne University Press, 1956.

7 K Kupka, Un art a l’état brut, La Guilde du Livre, Lausanne, 1962; K Kupka, Dawn of Art, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1965.

8 Now the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) in Canberra

9 H Groger-Wurm, Australian Aboriginal Bark Paintings and their Mythological Interpretation, vol. 1: Eastern Arnhem Land, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1973.

10 S Le Brun Holmes, Yirawala: Painter of the Dreaming, Hodder and Stoughton, Sydney, 1992.

11 JA Davidson, ‘Mathaman: Warrior, artist, songman’, Art Bulletin of Victoria, no. 29, pp. 4–23.