Curator Andy Greenslade writes about the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Art collection for the National Museum’s August 2011 Goree magazine.

An extraordinary collection of art – and other things – came to the Museum in 2007. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Art collection, which represents almost 40 years of collecting by various Australian Government agencies for Aboriginal affairs.

After being closed by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Amendment Act 2005, packers and carriers arrived at ATSIC offices around the country to remove assets – the pictures from the walls, the carved animals, the baskets and fibre ware, spears, trophies and posters. In fact, anything that related to art or was considered of enduring interest was removed.

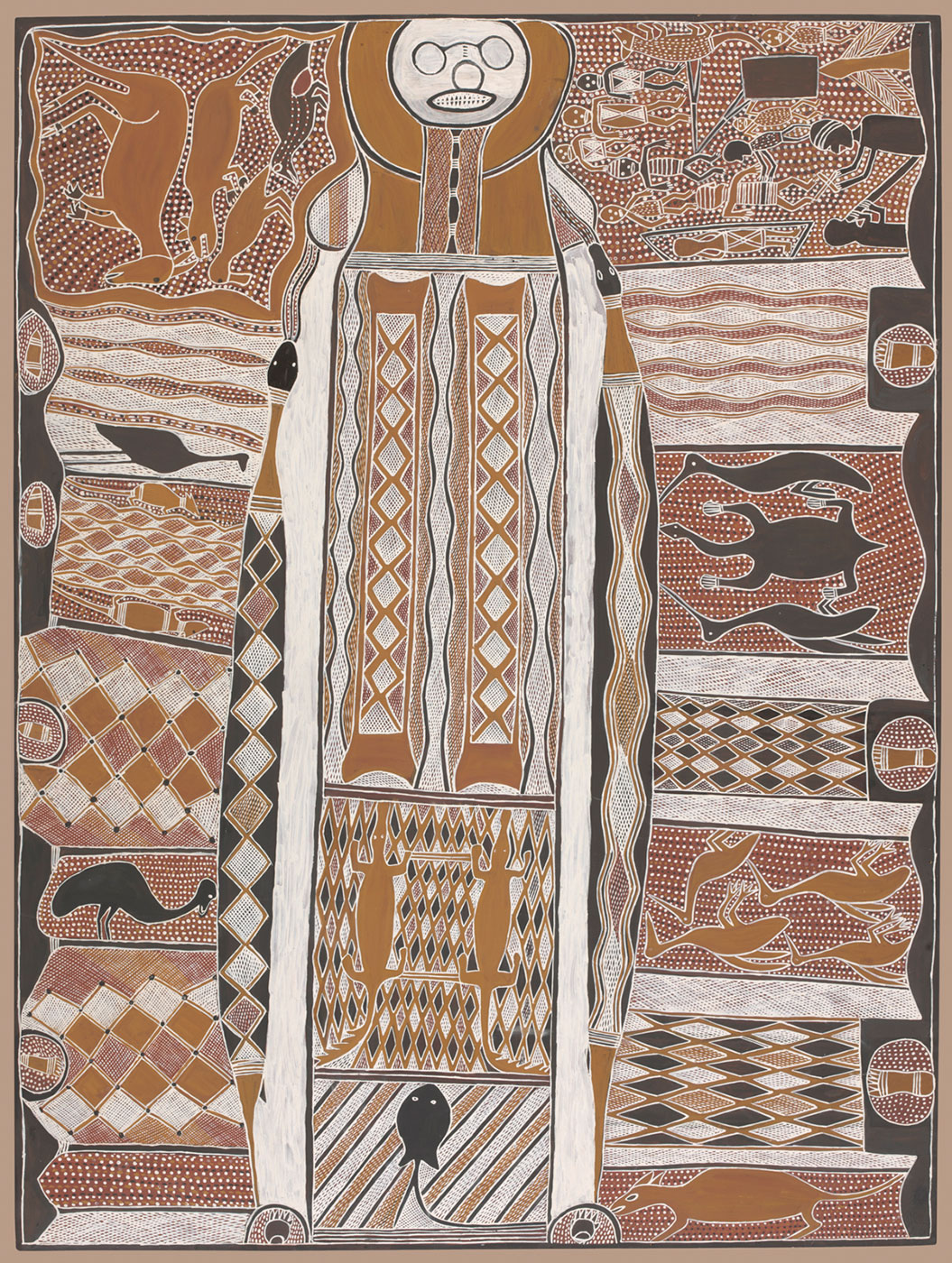

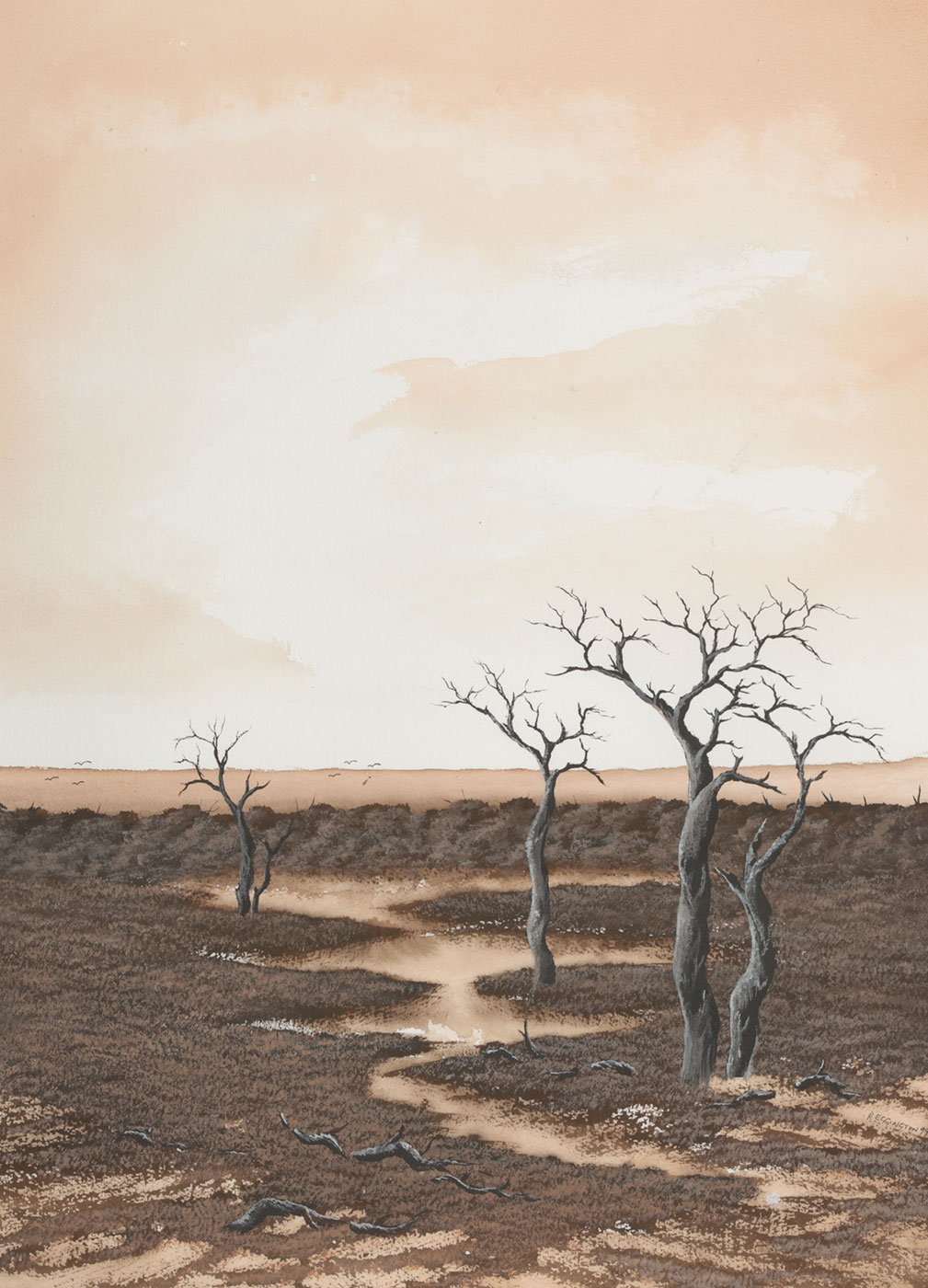

They found most things hanging on the walls of the offices – fabrics and rugs from Ernabella, watercolours from Hermannsburg and from Western Australia's Carrolup art tradition, bark paintings from across the Top End, and paintings from Papunya.

All of these and more were taken to Sydney for storage until a decision could be made on what to do with these works, which are considered of national interest.

The Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination (OIPC) became the next custodian of the collection and it was charged with the task of finding a permanent home for the collection's approximately 2,000 objects.

After a period of negotiation with various institutions it was decided that the collection would be transferred to the National Museum, where it would be kept together in perpetuity in the National Historical Collection.

The collection as historical record

It was an unusually large collection – much larger than the Museum would normally accept. But this collection is much more important than the sum of its individual artworks. The collection is an 'historical record', charting the years over which it was collected.

Objects as witnesses

The paintings, posters, carvings and weapons had witnessed all the comings and goings in the offices of various, now-defunct, Aboriginal Affairs agencies. These objects watched silently as politicians and community representatives, who had formed policy, argued over the best way to support communities, and how to service programs within communities. Just as those objects were silent witnesses to that history in the making, they have also come to reflect the human aspects unique to each of the local offices.

Missing elements

This collection is remarkable, yet there is surprisingly little documentation on a good proportion of the works. There is also a lack of information on procurement processes and even the rationale behind the gathering of such a large collection.

In the absence of a clear story, we use the objects to draw our own conclusions about their purpose and what they witnessed, or even their significance in local and national events.

Some objects may not represent any theme or purpose – perhaps they were just acquired to adorn the walls of the offices and in support of then fledgling art movements, some of which grew into significant movements in the international art scene.

There are, however, some solid facts that stand alongside any assumptions we make about this collection as a whole and the individual objects within.

Much more than the 'ATSIC collection'

To refer to it as the ATSIC collection is a misnomer, for the collection was not all acquired by ATSIC and much of it was inherited from earlier institutions. In fact, there were many more years of collecting art and objects than ATSIC existed. Pieces were acquired by a number of different bodies. They were the Council for Aboriginal Affairs (CAA), the Office of Aboriginal Affairs, the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, the Aboriginal Development Commission and, later, ATSIC.

The earliest purchases were by the CAA soon after its formation following the 1967 referendum. Dr 'Nugget' Coombs, Professor WEH Stanner and Barrie Dexter, who had been invited by Prime Minister Harold Holt to form the CAA, decided that they would only hang Aboriginal art on the office walls. Dexter, who recently visited the Museum to see a part of the collection that is in storage, mentioned that if there was any money left in the CAA budget, towards the end of the financial year, it would be put towards adding to the collection.

This early period was clearly an exciting time in arts as well as in politics. The announcement to begin building the National Gallery of Australia was made in 1967 and, in 1973, Jackson Pollock's famous and controversial painting, Blue Poles, was purchased for a record sum. Perhaps this atmosphere, and the formation of the Aboriginal Arts Board (AAB) in 1973, inspired the CAA to purchase the artwork to decorate its offices. In fact, a number of items in the collection bear the marks of acquisition through the Arts Board.

Changing character of the collection

The character of the collection changed as it passed from one agency to the next during the 38 years between the establishment of CAA in 1967 and the closure of ATSIC in 2005.

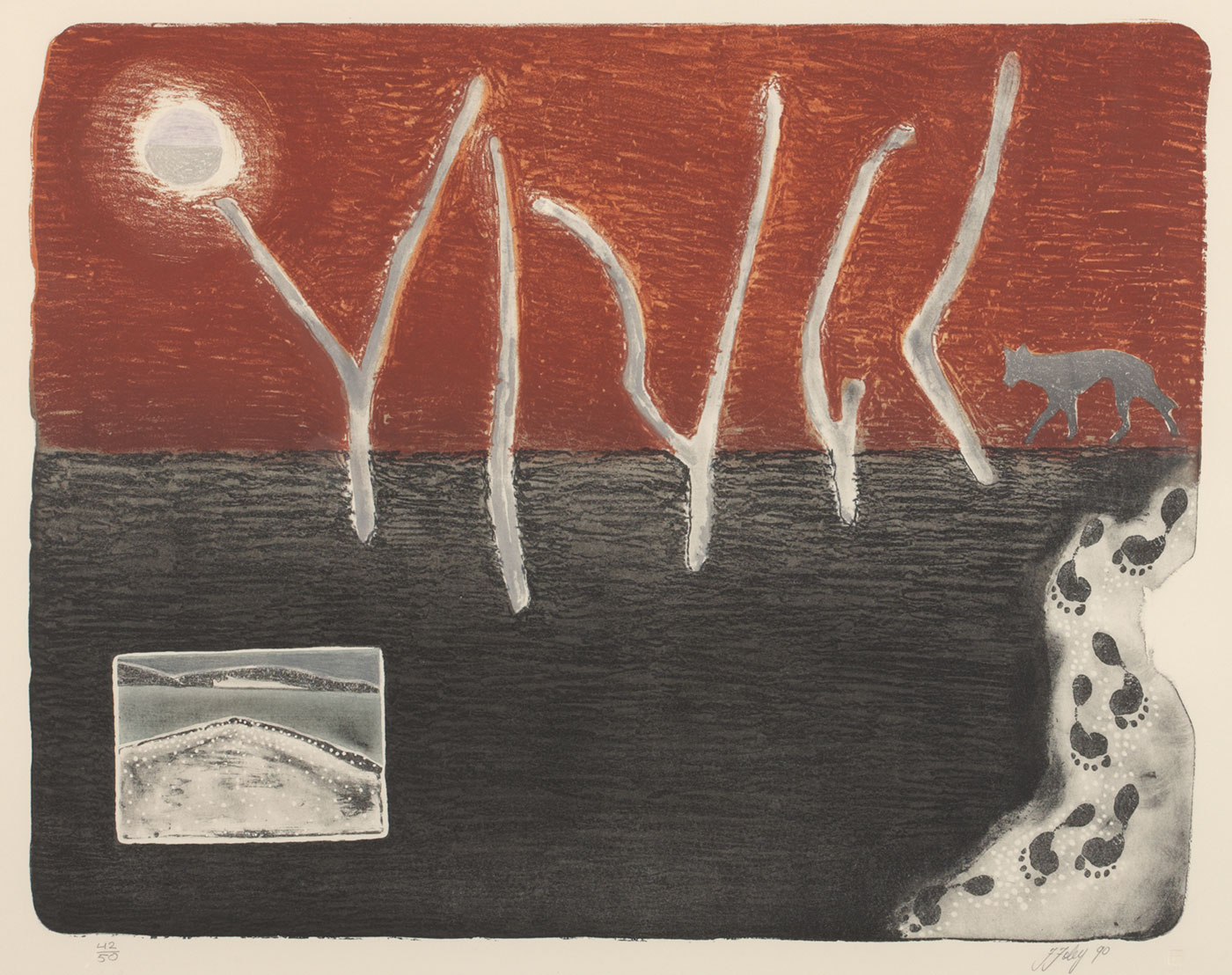

While the early years saw the acquisition of bark paintings, carvings and watercolours, and some of the early Papunya acrylic paintings, artworks collected in later years bear witness to the growth of other movements in art, such as the development of printmaking as a viable medium for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists.

As a result, the collection can be viewed as a 'snapshot' of 38 years of art production that reveals and records, amongst other things, the introduction of acrylic painting to communities across Australia; the demise of wool work at Ernabella and the growth of the centre's iconic batik tradition; an expanding and enduring watercolour movement in Western Australia and in Hermannsburg; increasing production of art for the tourist market; and the spread to many outer and coastal areas of the desert region style of dot painting.

A chronicle of contemporary events

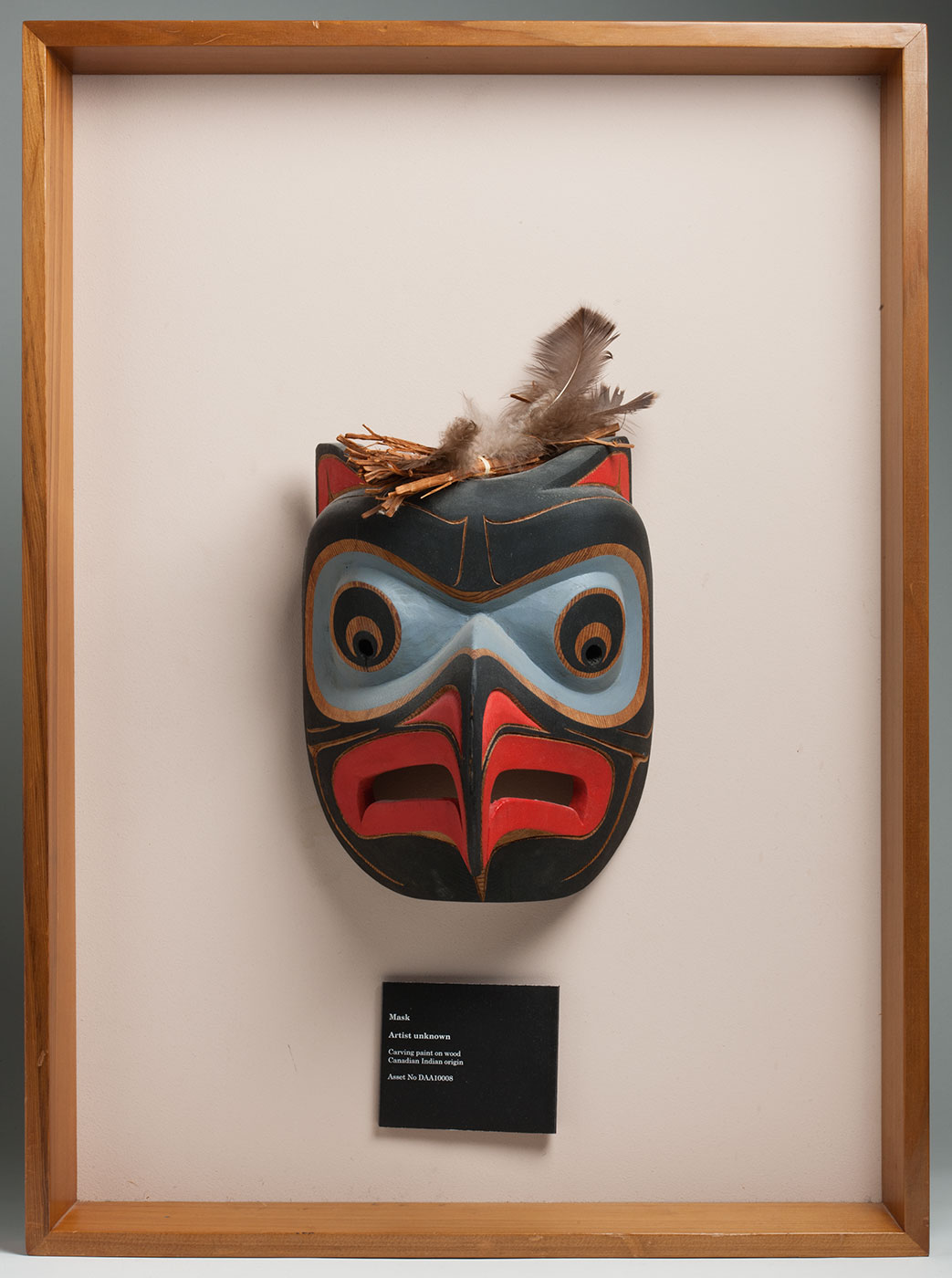

The presence of certain works can also reveal much about the circumstances that existed at the time the object came into the collection. For example, a stunning Canadian First Nations mask was given to Charles Perkins at the World Council of Indigenous Peoples conference that was held in Canberra in 1981.

There is a group of paintings, also, that clearly relate to health issues. We have been told that these were painted when a Northern Territory initiative to promote healthy lifestyle choices was carried out in the 1990s. It is likely that these works were transferred, perhaps to ATSIC, from the then Healthy Aboriginal Life Team (HALT).

What we do know is that copies of these original paintings were used in the communities to deliver essential health messages. Many of these works were painted by Andrew Spencer Tjapaltjarri and his wife Bertha Dickson Nakamarra.

In the collection there is also a small number of documents clearly valued by ATSIC, including copies of the proclamation of recognition in 1995 of both Harold Thomas's Aboriginal flag, and of the companion Torres Strait Islander flag designed by Bernard Namok, under the Flags Act 1953.

Explore more on Off the Walls