Clocks and chronometers, furniture and musical instruments, glassware and crockery, dolls and toys, bark paintings and stone tools – all these and more come under the care of conservators working in the objects and paintings lab.

These conservators look after the greatest variety of objects in the National Museum’s collection. The range of skills required of conservators continues to grow as more modern materials and technology items are added to collections.

Conservators Andrew Pearce, Peter Bucke and Natalie Ison describe their backgrounds, training and work at the National Museum of Australia.

Some conservators specialise in a particular material or object type – for example metals or furniture – but many are multi-skilled and able to treat a range of objects.

The same person might switch from peering through a magnifier to dismantle a clock with tweezers, to repairing the mechanical parts of a parasol, reassembling an old television camera, or using a brush-vacuum to clean a grass sculpture.

Conservators working in all areas of the Museum practise minimal intervention. This means treating the object as little as possible to make it stable and preserve its significance.

Caring for canvases and bark paintings

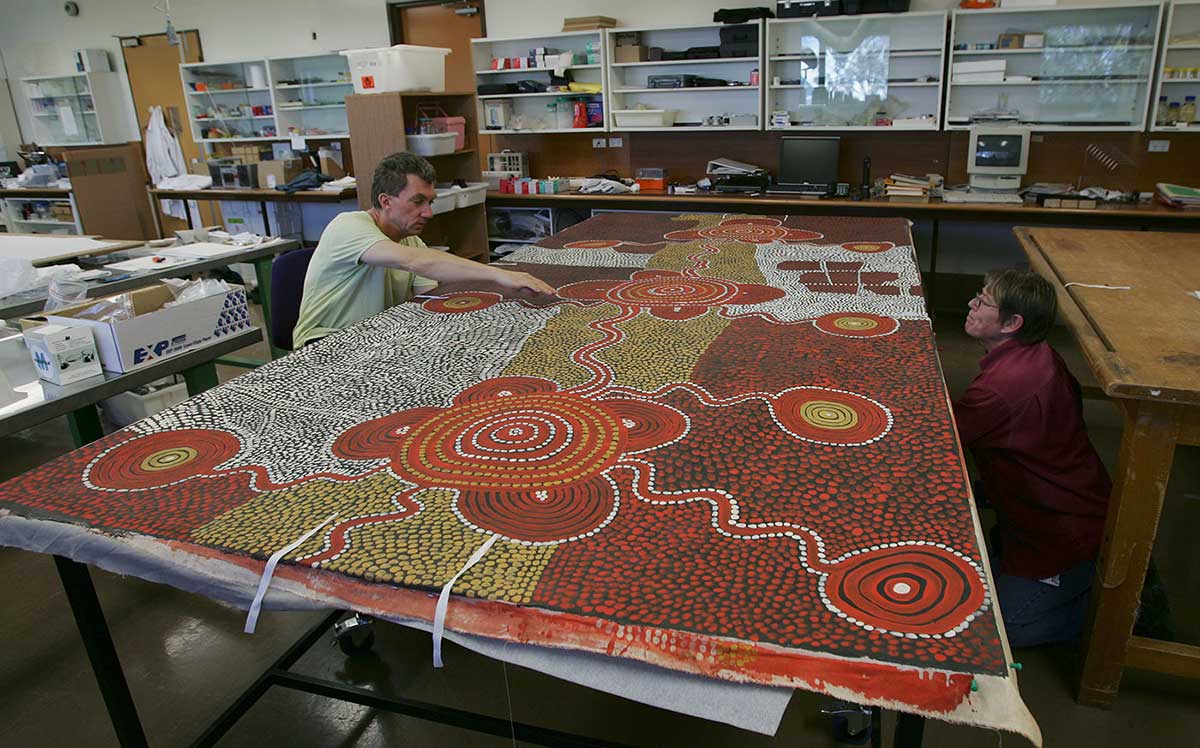

Conservators in the objects and paintings lab stretch paintings to keep canvases taut and prevent damage during storage or display. Loose canvases respond to changes in humidity, which can cause paint layers to separate from the surface. Paintings can be stretched on either stretchers or strainers.

Conservators opt for stretchers because, unlike strainers, they are adjustable. Keys in the corners of the stretcher allow tension to be fine-tuned as the canvas expands and contracts, preventing it from becoming too taut or slack. All stretchers are custom-made to fit the artworks.

The Museum also holds an extensive collection of Aboriginal bark paintings. These works are inherently unstable. The bark can split and crack with changes in temperature and humidity, causing extensive structural damage to the object. Traditionally, plant resins and animal fats were used as binders to hold together the particles of ochre pigment and fix them to the surface of the bark. Resins and fats can deteriorate over time, causing the paintwork to flake or crumble.

Conservators carry out structural repairs to the bark in several ways, including using splints of Japanese repair paper. Then individual flakes of pigment are meticulously reapplied to the bark using tiny dots of adhesive.

Chronometer conservation

Eleven chronometers were dismantled, examined, cleaned and serviced during Museum Workshop.

The Tobias model was made around 1830 which makes it one of the oldest chronometers in the Museum's collection. The movement is unique as it has two separate bridges, one housing the fussee and mainspring barrel, and the second housing the wheel train and escapement.

The movement was in poor condition, with old lubricants restricting its operation. It was disassembled, cleaned, adjusted and relubricated was was restored to working order.

Storing glass plate negatives

Masters student Steven Kramer describes his internship project on the storage of the National Museum's glass plate photography collection.

You may also like