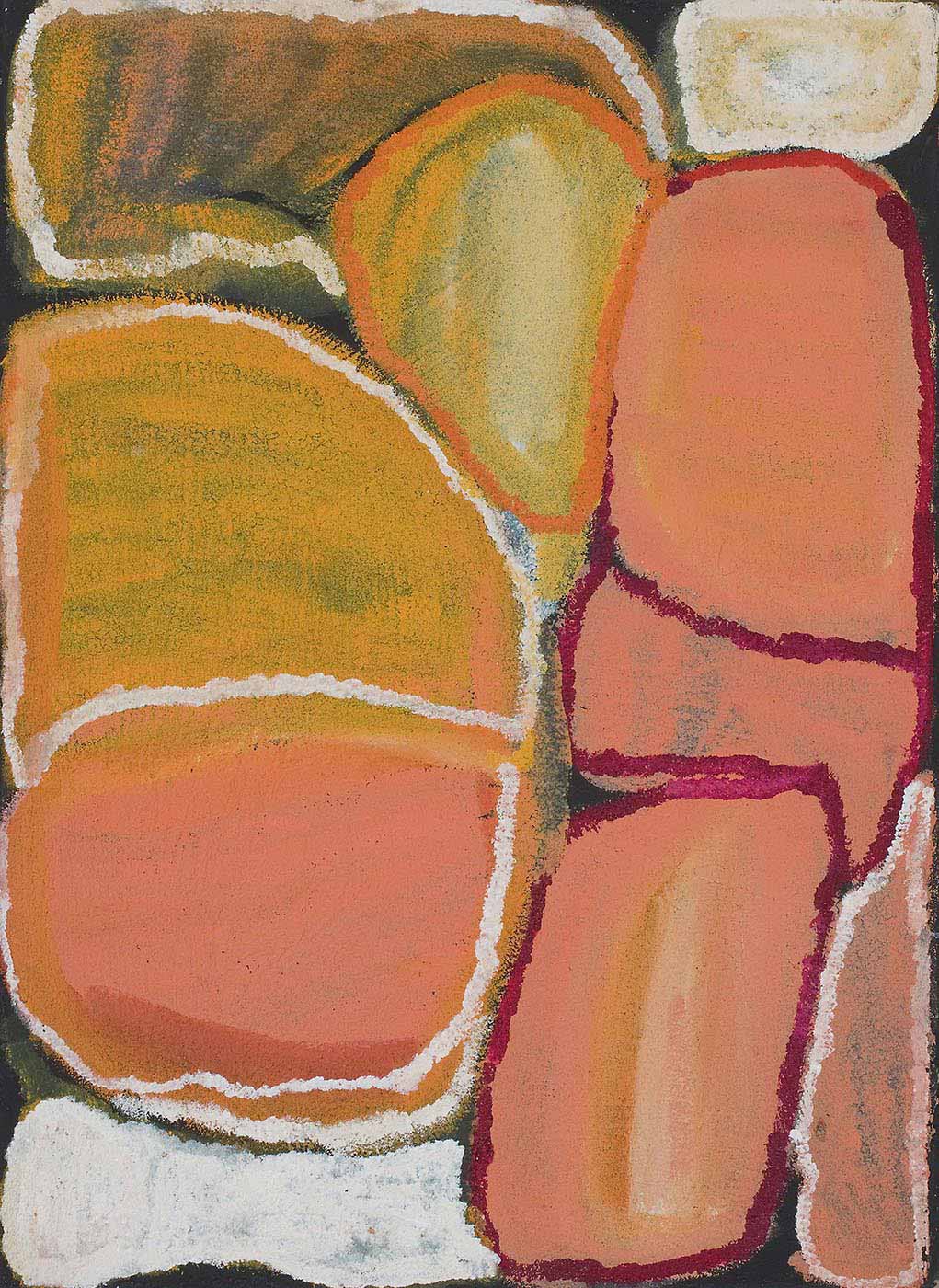

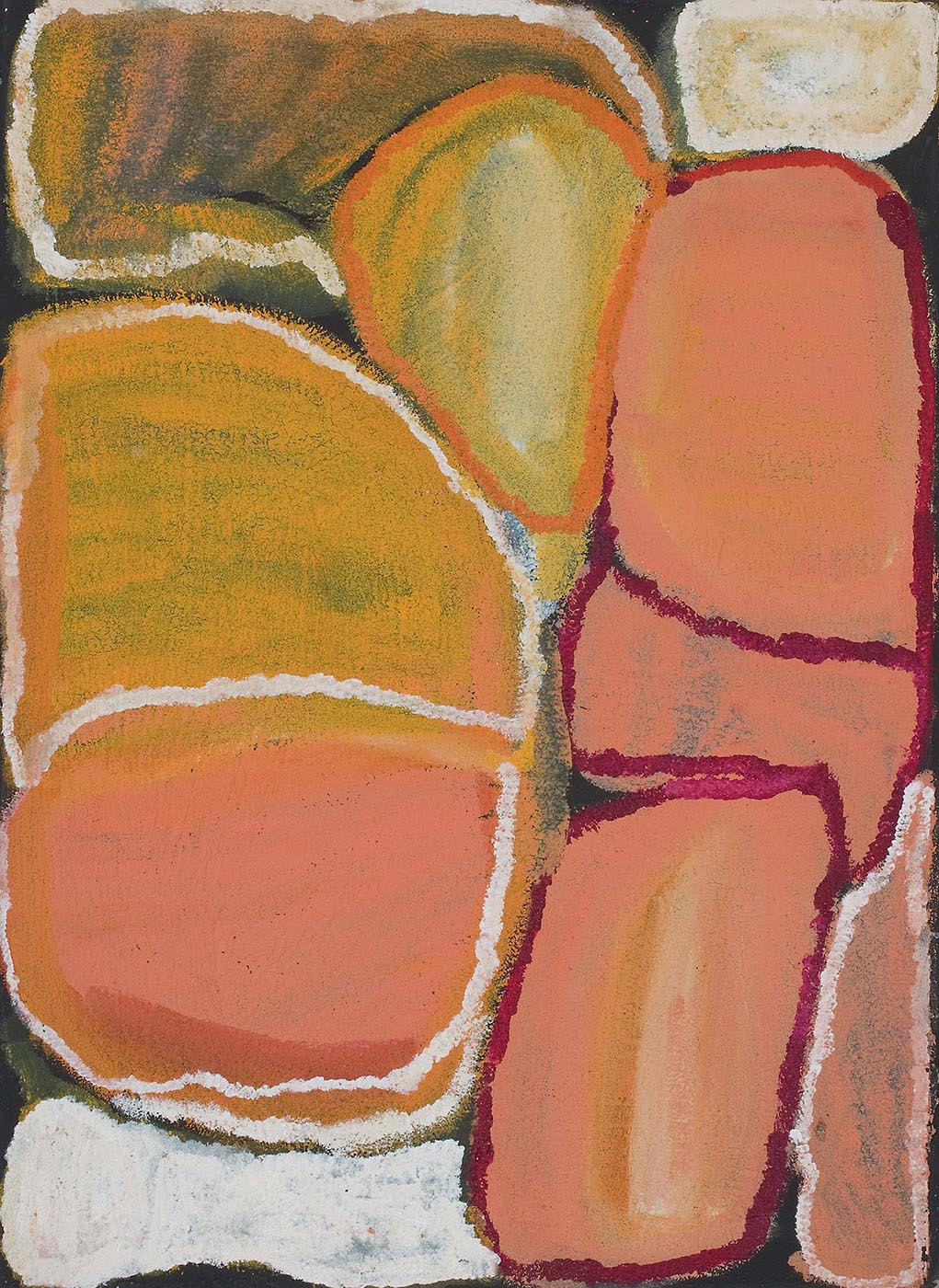

Kumpaya Girgaba, Parnngurr, 2009:

People all scattered, travelling on that Canning Stock Route. That’s why everybody left. All gone everywhere: Wiluna, Jigalong, Fitzroy, Balgo, everywhere.

This painting depicts Nyilnigil, a big water in Nyangkarni’s country, which is surrounded by white gum trees called tinjilypa. Nyangkarni was among the last of the desert people to travel north from her homeland in the jila country to the Fitzroy Valley.

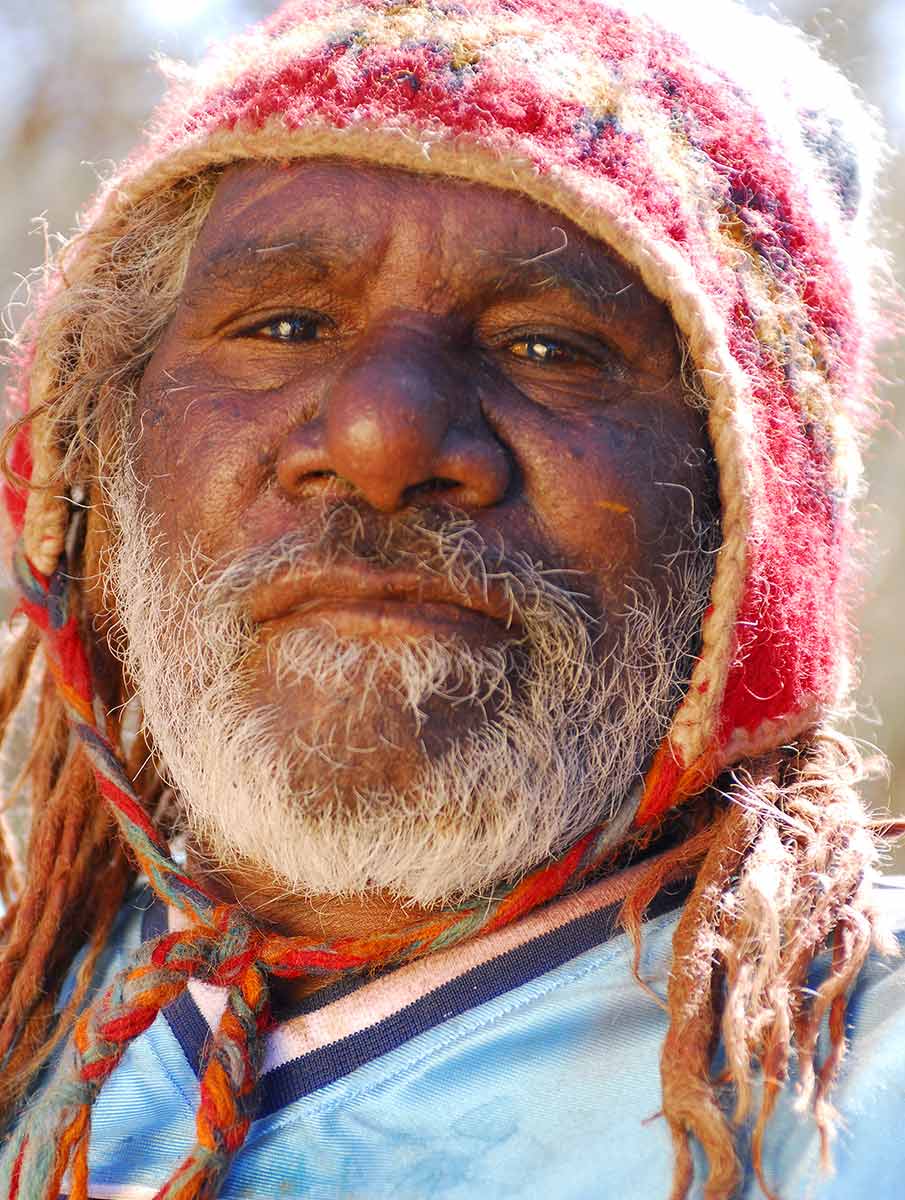

Nyangkarni Penny K-Lyons:

We are lost in our country. Nobody’s here.

In this human drought, a pair of murderous Aboriginal men were preying on the few people remaining in the desert. The artist was kidnapped by one of these men, who killed her grandmother and took Nyangkarni as his wife. She cleverly led him north to the cattle stations where she was re-united with her family.

The Canning Stock Route story revolves around water. Alfred Canning needed to find significant water sources, a day’s walk apart, where wells could be dug. The drovers following Canning would need to water up to 800 head of cattle at each well. These herds could consume more than 30,000 litres of water at a time.

To colonists, desert water was a commercial resource necessary for a successful stock route. To the people of the desert, these waters were the social, spiritual and economic bases of their existence.

The wells built by Canning often made vital waters inaccessible to desert people who relied on them for survival. Such waters, therefore, became sites of conflict between cultures.

In 1907 a member of Canning’s party, Michael Tobin, was fatally speared at Natawalu (Well 40) by a man called Mungkututu who Tobin shot moments before he died. Many other tragic events would occur around these wells in the decades that followed.

While the Natawalu incident was documented by Canning’s party, many other conflicts around the Canning Stock Route were not. They are, however, remembered by desert people. Today desert art provides the means for such stories to be told and recorded.