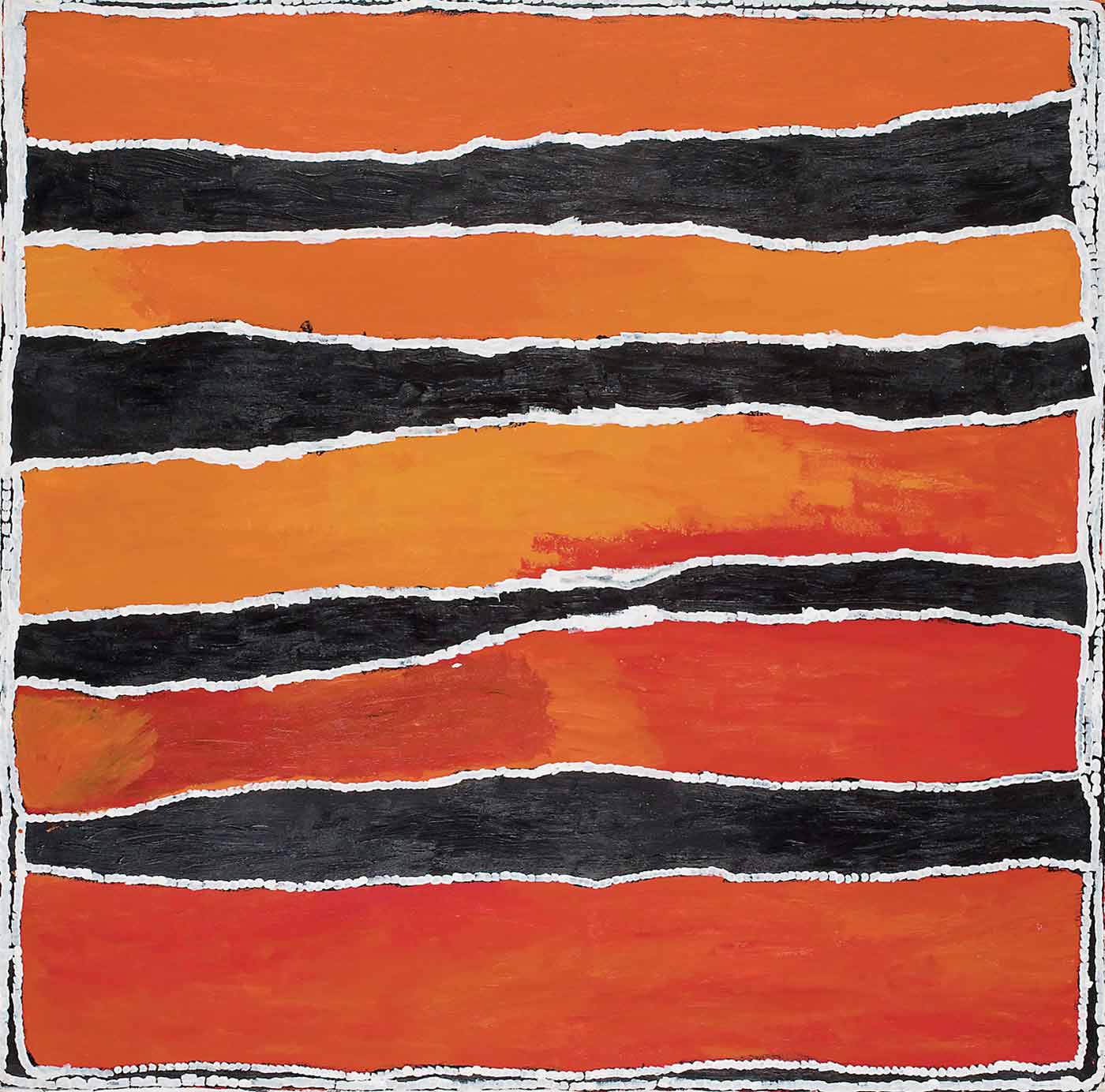

Jeffrey James, Pangkapini, 2007:

They were all soaks … and became to be a well by the Canning. All soaks and rockholes, Martu’s water right through.

Mayapu Elsie Thomas:

At Natawalu an Aboriginal man speared a kartiya [white man], then that kartiya got a rifle and shot him. Right [at] Natawalu. Before there was a well there. That’s the place I painted now. He was just coming to get water ... then he saw that kartiya. He speared him then, near the water.

Alfred Canning, in his evidence to the royal commission, 1908:

We saw a native running towards us fully armed. He was watching Tobin all the time ... and just as the native moved with his spear Tobin raised his rifle and fired just after the native had discharged his spear which entered Tobin’s right breast. The native fell ...

The Canning Stock Route story revolves around water. Alfred Canning needed to find significant water sources, a day’s walk apart, where wells could be dug. The drovers following Canning would need to water up to 800 head of cattle at each well. These herds could consume more than 30,000 litres of water at a time.

To colonists, desert water was a commercial resource necessary for a successful stock route. To the people of the desert, these waters were the social, spiritual and economic bases of their existence. The wells built by Canning often made vital waters inaccessible to desert people who relied on them for survival. Such waters, therefore, became sites of conflict between cultures.

In 1907 a member of Canning’s party, Michael Tobin, was fatally speared at Natawalu (Well 40) by a man called Mungkututu who Tobin shot moments before he died. Many other tragic events would occur around these wells in the decades that followed.

While the Natawalu incident was documented by Canning’s party, many other conflicts around the Canning Stock Route were not. They are, however, remembered by desert people. Today desert art provides the means for such stories to be told and recorded.

Killing the snake

Cross-cultural conflict took different forms on the Canning. Sometimes history and the Dreaming did not simply intersect, but clashed with dramatic and lasting effect. Kulyayi, an Aboriginal water that became Well 42, is the clearest expression of this.

Of the 200 permanent springs in the country on the north-western side of the stock route, about 30 are inhabited by the powerful ancestral beings known as jila or kalpurtu (rainbow serpents).

During the excavation of the well the great rainbow serpent Kulyayi was killed by white men. Some accounts say Kulyayi was killed by explosives, while others suggest he rose up in anger and was shot dead. Recent accounts also stress the human impact of the cultural clash.

Lloyd Kwilla, Wangkatjungka, 2009:

It’s like an icon, like Sydney Harbour Bridge. If someone came and bombed that, blew it away, people would be devastated, empty. That place would be changed. Well, people felt empty when he [Kulyayi] was gone. They felt something not there anymore, they can’t come back. They moved away. Animals moved away. People, animals, they're connected. Something valuable was lost, you can’t replace it.

The story of Kulyayi challenges a common view of the Dreaming as mythic events outside of ‘history’. It reveals the environmental logic of Aboriginal beliefs: the death of the rainbow serpent expresses the profound impact the Canning Stock Route wells had on the ecology of desert country.