The Not Just Ned exhibition developed by the National Museum of Australia features stories and objects which document more than two centuries of Irish transportation and immigration.

About half a million Irish men, women and children left their homes to begin the long sea passage to Australia between 1788 and 1921, when Ireland gained independence. About 12 per cent of these people made the journey in the hold of a convict ship.

Stories featured here include Irishman and First Fleet surgeon-general John White, colourful pickpocket and later police chief George Barrington, Young Ireland rebellion leaders Thomas Francis Meagher and William Smith O’Brien, the convict women who made the Rajah quilt, and pioneer chaplain Charles Beaumont Howard.

Transportation

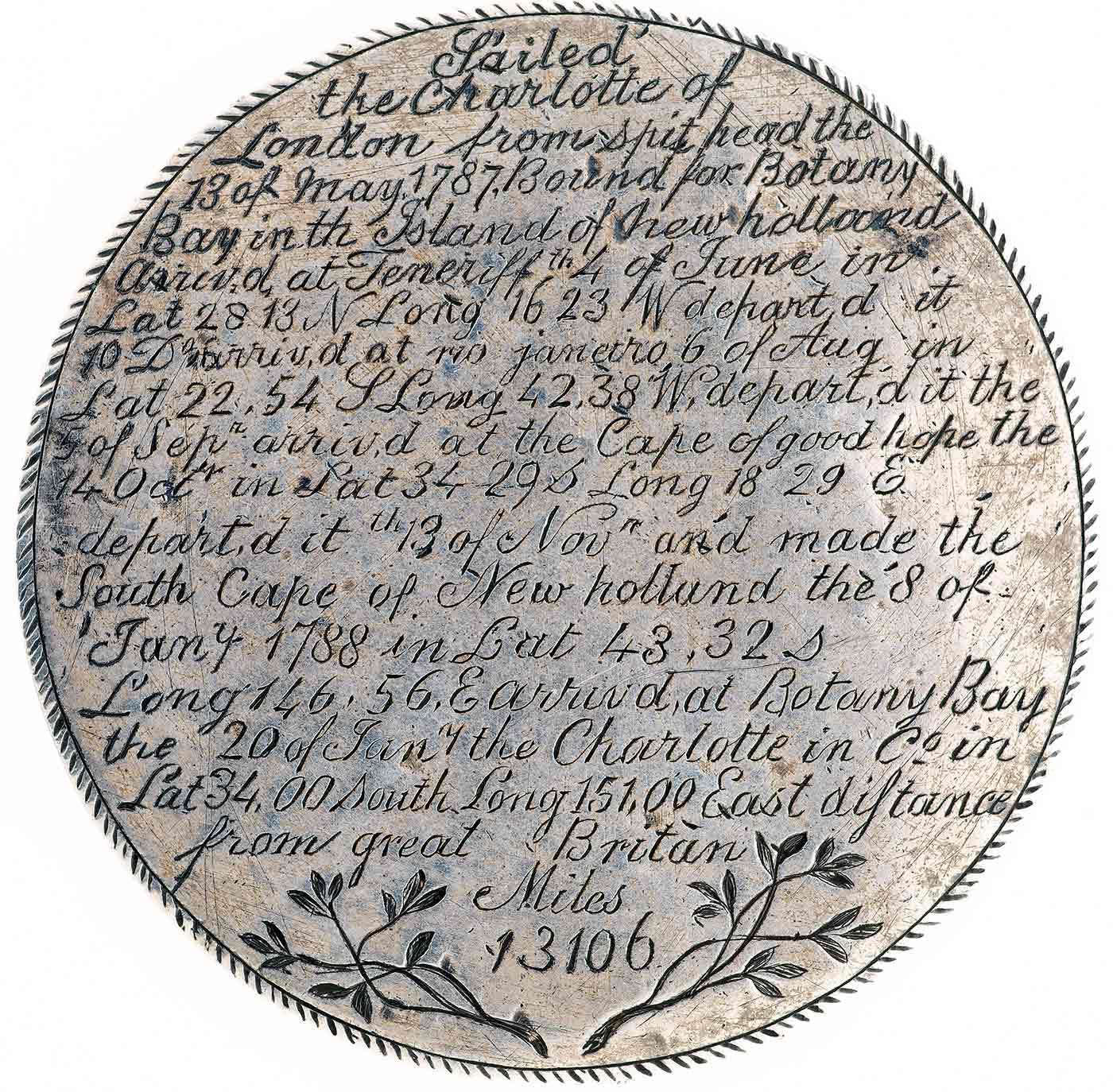

The Charlotte medal

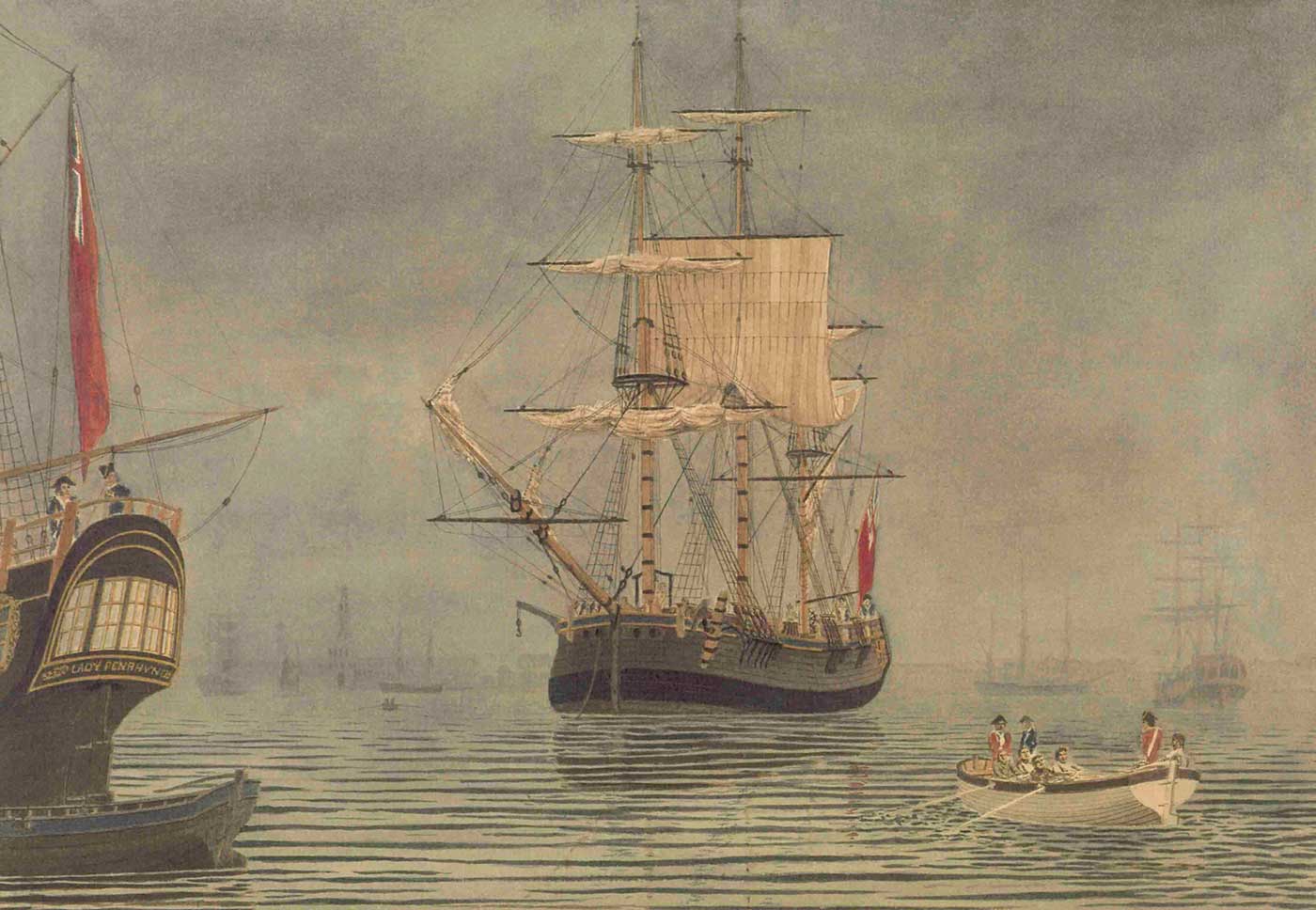

Irishman John White, surgeon-general of the First Fleet, was impressed with the forger Thomas Barrett, who sailed with him in the convict transport Charlotte.

On 5 August 1787, as the ship lay at anchor off Rio de Janeiro, Barrett was caught passing forged ‘quarter dollars’ to local boatmen to pay for food. White was amazed at how Barrett had managed to manufacture these coins without seemingly having had any access to fire or the other equipment necessary for coin-making.

Perhaps it was this knowledge of Barrett’s skill that led White to commission the convict to engrave a medal celebrating the ship’s safe arrival in Botany Bay on 20 January 1788.

The Charlotte medal is regarded as Australia’s first colonial work of art. On one side, it depicts the ship resting at anchor in Botany Bay and on the other, precise details, in terms of latitude and longitude about the major places they either passed or stopped at during the eight-month voyage.

Barrett did not survive long in the colony. After little more than a month, he was hanged for stealing food, an event recorded by White in his famous Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (1790): ‘Barrett was launched into eternity, after having confessed to Rev. Mr Johnson, who attended him.'

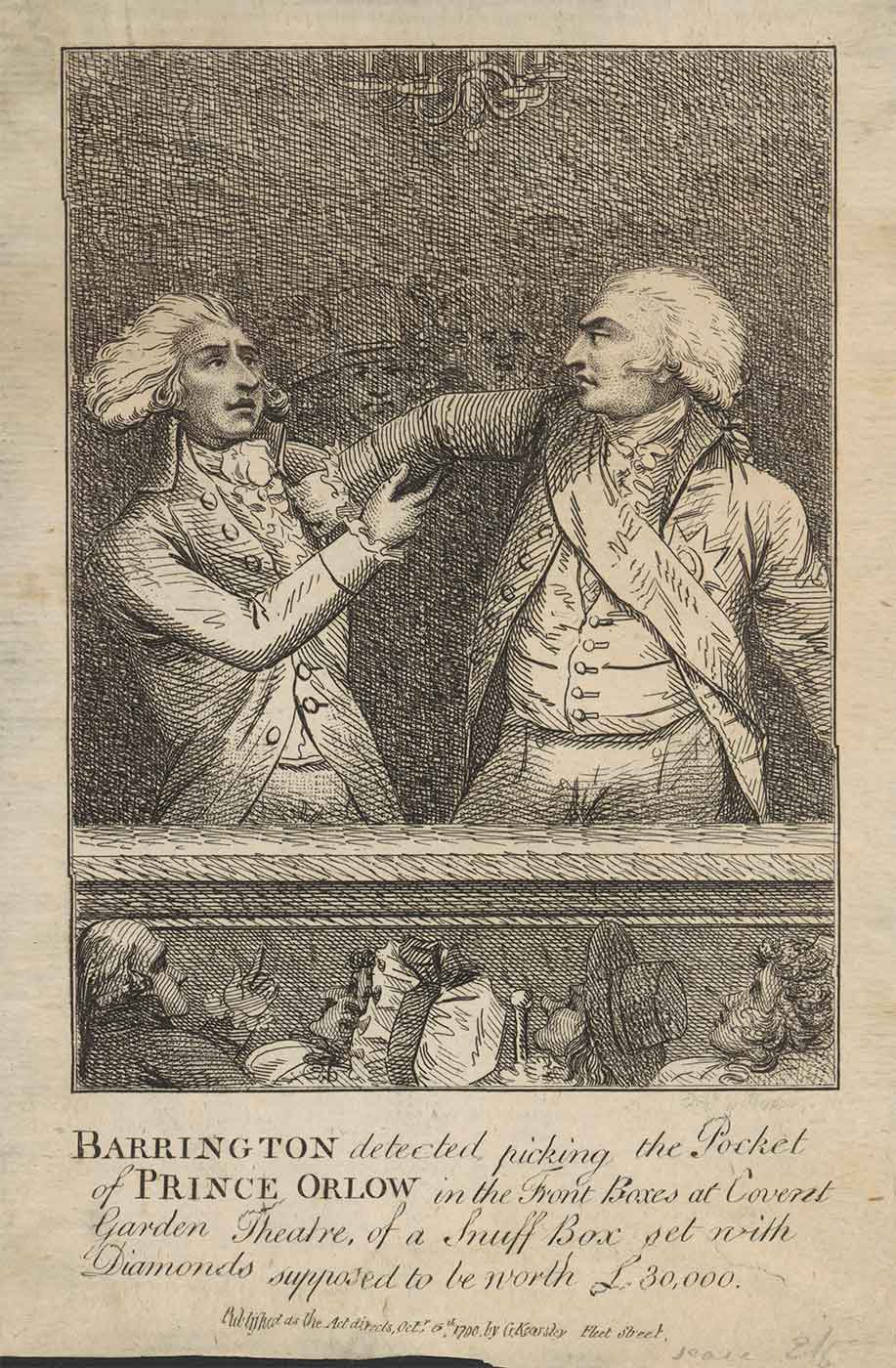

George Barrington, prince of pickpockets

George Barrington’s early life in mid-18th century Ireland has been described as ‘masked by romantic versions of infinite variety’, including a claim to be of royal descent.

Sent to a Dublin school to prepare him for university, Barrington got into a fight with another boy and stabbed him. Punished with a flogging, he bolted with a stolen watch and some money.

He took up with a group of strolling players, and was taught to pick pockets by their leader, the notorious English swindler John Price.

By the mid-1770s Barrington was well on his way to becoming London’s most colourful pickpocket. He lived in great style, mixing easily with gentlemen, and just as readily stealing their purses. Although he was arrested many times, he used his connections to get acquitted.

One of his most famous exploits was the attempted theft of a diamond-studded snuff box, allegedly worth £30,000 — a vast sum in those days — from the Russian Prince Orlow at Covent Garden. Hauled before the magistrate, Barrington pleaded his case with such a display of emotion that the prince refused to press charges.

The Irishman’s luck ran out in 1790. For the theft of a gold watch he was transported to Sydney, where his ‘irreproachable conduct’ eventually gained him an absolute pardon. In 1796 he was even appointed chief constable at Parramatta — one wonders if he ever arrested anyone for picking a pocket.

The Rajah quilt

The Rajah quilt is an extraordinary testimony to the skill and perseverance of a small group of female convicts who arrived in Hobart in 1841. It speaks to the experience of women during their journey to Australia. It is the only known surviving convict shipboard quilt and one of only a few objects relating to Australia’s convict women.

Thirty-seven of the 180 women on board the Rajah were from Ireland. The quilt’s 2185 fabric pieces were sewn together using needles, thread and patchwork pieces provided by the British Ladies’ Society for the Reformation of Female Prisoners. The quilt was made in the medallion style popular in the late 18th century in England and Ireland. On arrival in Hobart the quilt was presented to the Lieutenant Governor’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin.

More than 9200 Irish convict women were sent to Australia. Most eventually married, raised families and led ordinary lives. To their overseers in the colony there was only one thing worse than an Irish convict man — an Irish convict woman. Governor Philip Gidley King called them ‘thoroughly depraved and abandoned’. Reverend Samuel Marsden saw three evils in the colony: alcohol, the Catholic religion and Irish female convicts.

The National Gallery of Australia in Canberra acquired the Rajah quilt in 1989 and it has become one of the most requested objects for viewing at the gallery. The quilt is very fragile and usually only on display once a year.

Young Ireland

Regarded by the British as traitors, William Smith O’Brien and Thomas Francis Meagher were held in high esteem by their countrymen.

Both were leaders of the ill-fated 1848 ‘Young Ireland’ rebellion, which took place at the height of the Great Irish Famine of 1845–50, and both were sentenced, as convicted traitors, to be ‘hanged, drawn and quartered’. In 1849 this dreadful sentence was commuted to transportation for life to Tasmania.

Three years later, Meagher escaped on a ship to the United States, where his career became the stuff of legend. In the American Civil War he rose to be a general in the Union army, commanding the ‘Irish Brigade’.

To fight for the Union, he declared, was to fight for Ireland, since Ireland could not hope to become a republic without the support of the ‘liberty loving citizens of the United States’.

During the war he was presented with two dress swords by Irishmen wishing to honour his ‘sterling devotion to the cause of Ireland and of liberty’. These swords recall the name given to Meagher in Irish national history — ‘Meagher of the Sword’.

In 1846 this rebel had asserted that armed insurrection against tyranny was justified: ‘I look upon the sword as a sacred weapon ... for at its blow, and in the quivering of its crimson light, a giant nation [the United States] sprang from the waters of the Atlantic.'

Meagher drowned in the Missouri River in 1867 while serving as acting governor of the Territory of Montana. His body was never recovered.

William Smith O’Brien is perhaps the best remembered of the Young Ireland rebel leaders. A member of the aristocratic O’Brien family, direct descendants of Ireland’s great High King, Brian Boru, he initially refused to give his word not to escape in Tasmania and was confined, first to Maria Island and later to Port Arthur.

His defiant stance was driven by the belief that to remain a prisoner would keep the cause of Ireland more directly in front of world opinion. In November 1850, however, he gave his parole and four years later received a ‘conditional pardon’. This allowed him to return to Europe, but not Ireland.

As he was passing through Melbourne, the colony’s Irish residents presented him with a magnificent gold cup produced by a local Irish goldsmith. A carved piece at the top of the cup shows a seated O’Brien receiving a laurel wreath of victory from Hibernia, the symbolic figure of Ireland.

Immigration

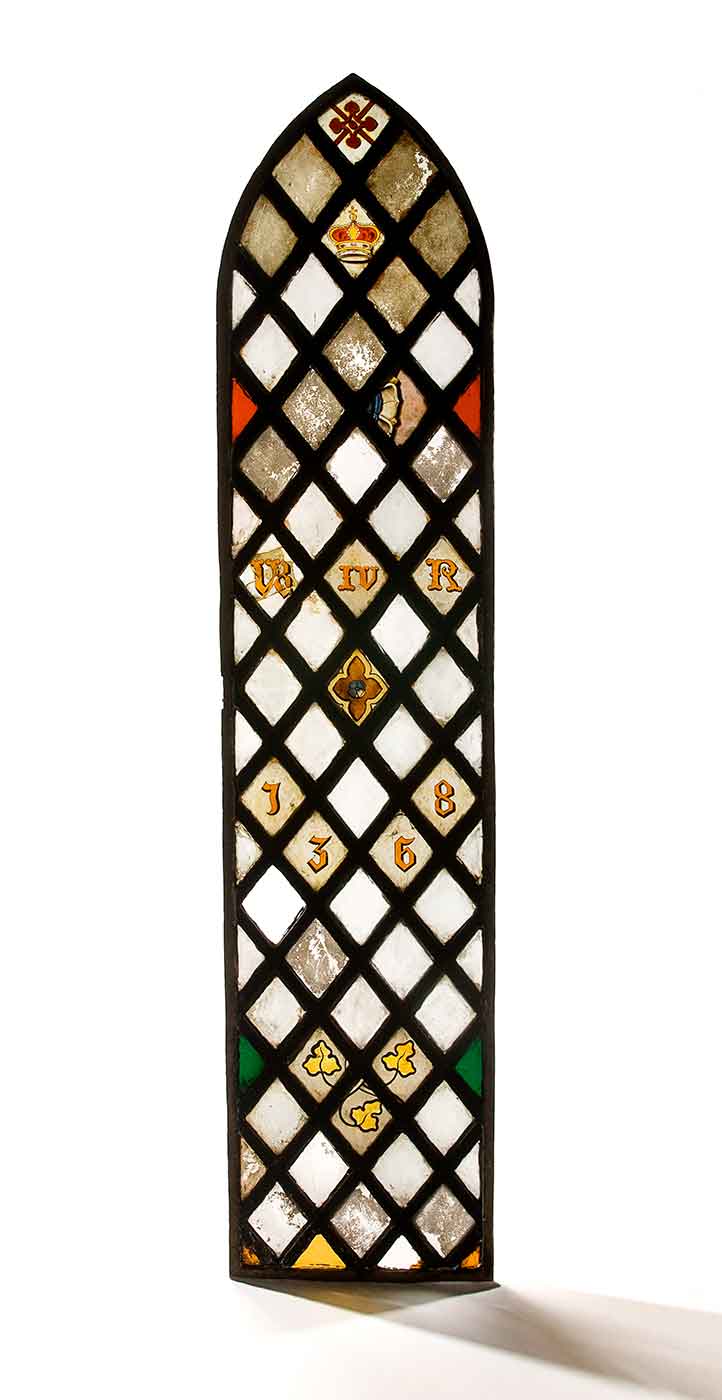

Pioneer chaplain

In colonial South Australia, Irishman Charles Beaumont Howard was known as the friend of anyone in trouble or distress. Howard was South Australia’s ‘colonial chaplain’, an Anglican clergyman who battled to establish his church in the Adelaide bush.

In 1836 a temporary church was sent out with Howard on the Buffalo. However, several weeks of attempting to conduct services in it after he arrived at Holdfast Bay, Glenelg, quickly proved it useless.

And so, in the extreme heat of late January 1837, Howard, assisted by the colonial treasurer, dragged a handcart and sail 12 kilometres through the bush to the site of the new city of Adelaide. There he erected the sail under a tree for shelter, surrounded the structure with tree branches and rushes from the coast and held Adelaide’s first Anglican services.

Howard’s greatest monument is the Holy Trinity Church, which he opened in 1838. But in the Holy Trinity Church collection is an object that perhaps better symbolises Howard’s pioneering efforts. It is a small stained-glass window, intended for the temporary church from the Buffalo, and decorated with the letters ‘WIVR’ (standing for the reigning monarch, William IV) and the date, 1836.