Brisbane Courier, 13 August 1913:

Mission stations had a splendid display, which speaks well for the training the aboriginals are obtaining … The exhibits came from Mapoon, Weipa, and Arukun. The work was exceptionally good … comparing favourably with the work in the schools section. In the collection was a chair made by a boy named Albert Mackenzie, and presented by him to the P.W.M.U. for the president’s use.

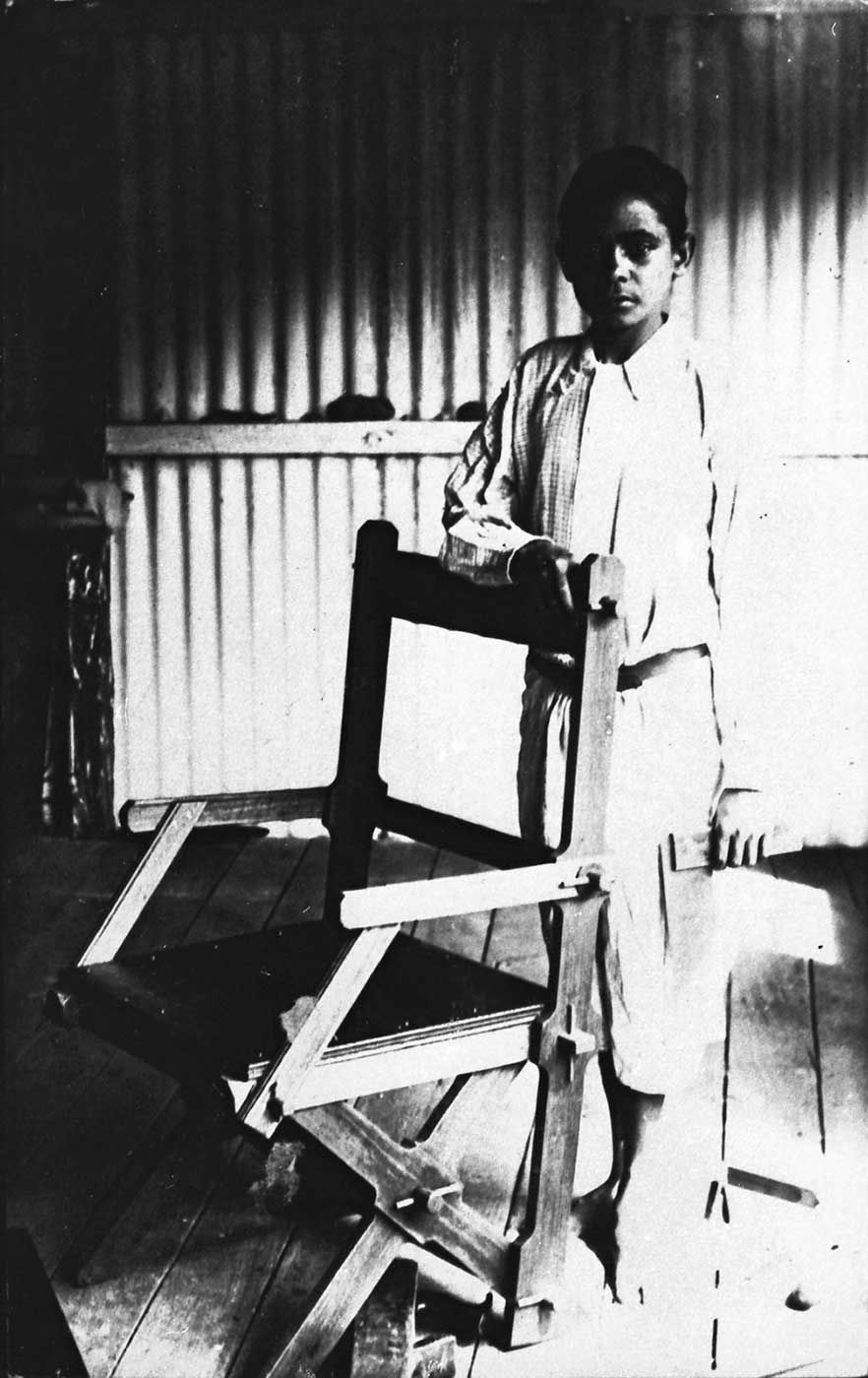

The missionary chair

Albert Mackenzie, a 15-year-old boy from the Weipa Presbyterian mission in far north Queensland, made this chair without using any nails. It was exhibited at the Brisbane Exhibition in August 1913 and reminds us how missionaries trained Aboriginal children to be ‘productive’ in ways that were valued by the colonising society. Boys were taught woodwork, leatherwork, welding and brickmaking, and girls learned to sew, crochet and cook. The chair was presented to the president of the Presbyterian Women’s Missionary Union (PWMU) of Queensland, to thank this philanthropic group of women for their financial support of the mission.

The ladies of the PWMU had been resourceful and successful fundraisers for about 20 years. Their most lucrative initiative was a cookbook, which sold more than 225,000 copies and was revised in 22 editions until 1981. From 1894 to 1900 the cookbook raised about £1500.

White Queenslanders learned about the local Indigenous communities through displays at the Brisbane Exhibition: in 1912, when Brisbane’s population was about 70,000, some 163,000 people attended show week. Most, however, had little direct contact with Aboriginal people, who had been driven out of the city.

Albert Mackenzie’s skilled work surprised many visitors. Newspaper reports commented on the ‘quality and range of the work’, and presented the samples of Aboriginal work on display as evidence ‘of the advance shown by the natives in the difficult process of emerging from their state of primitive barbarism into a condition approaching semi-civilisation’. The displays in the exhibition’s ‘Aboriginal Court’ enabled the state government to give the impression that Aboriginal people were compliant, useful workers, who not only could be taught new skills that contributed to the state’s economy, but were also safely segregated on missions and reserves.

While the chair was seen as a symbol of gratitude, respect, skill and appreciation, the ‘benign’ impression conveyed through such displays of craft was in striking contrast to the lived reality of many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Most Indigenous Queenslanders knew forced removals, high mortality rates on reserves, missions ravaged by epidemics and control imposed on their communities by the Aboriginals Protection Act of 1897.

The minutes of the PWMU meeting held in St Paul’s Hall on 5 September 1913 describe the president, Mrs Stewart, sitting in Mackenzie’s chair for the first time. In 1990 the chair was moved into the vestry of St Paul’s Presbyterian Church, Brisbane. In 2010 it was donated to the National Museum of Australia.

In our collection

Explore more first peoples