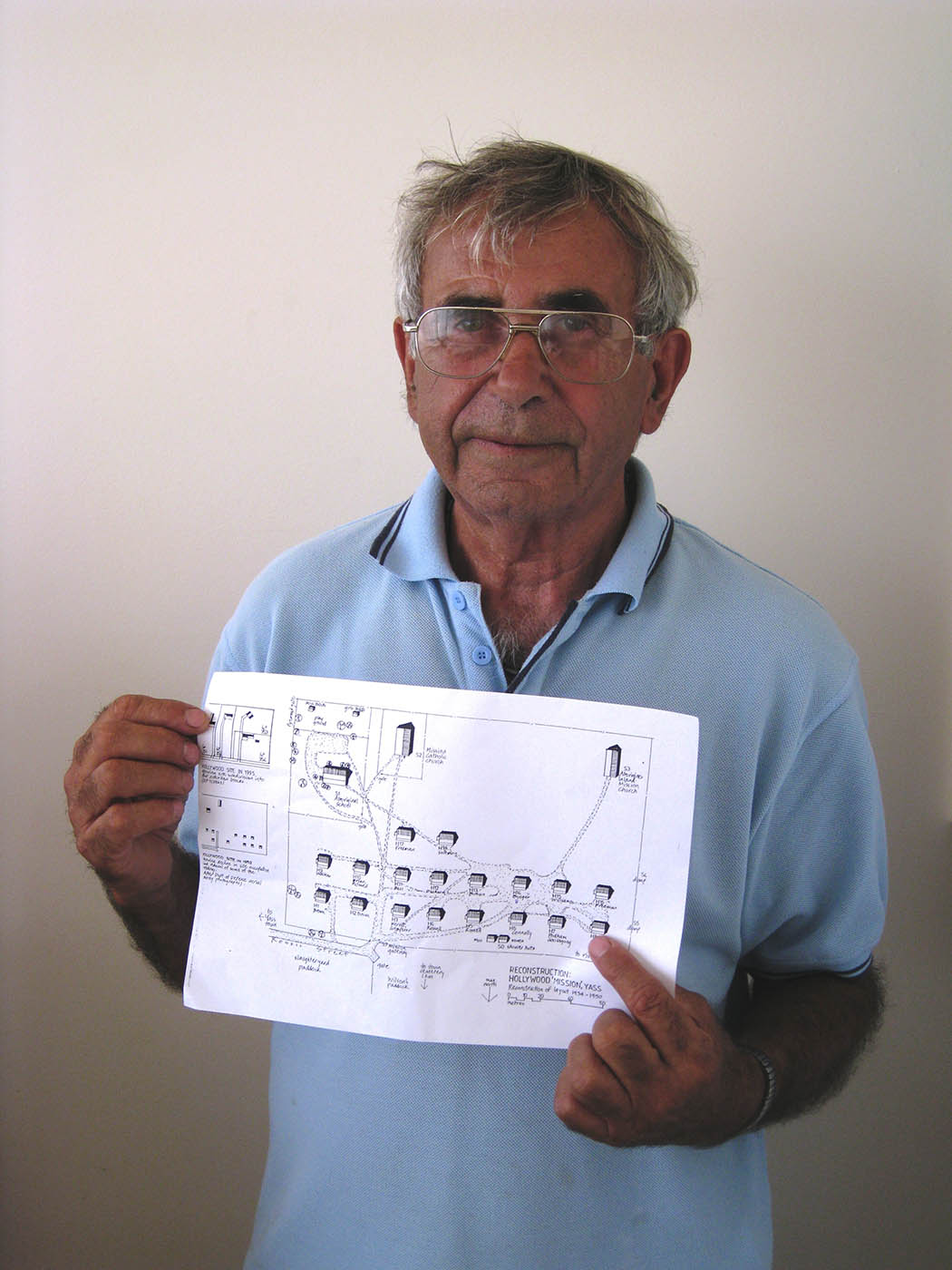

National Museum curator Karolina Kilian met Eric Bell at the Hollywood Mission site, in Yass, New South Wales

In 2009 I had the pleasure of visiting Eric Bell, a Ngunnawal elder, to record his childhood memories of growing up on an Aboriginal mission. Eric, like many Aboriginal Yass residents, grew up on Hollywood Mission, on the outskirts of town. Today, he is one of only a few people to remember what life was like on Hollywood Mission.

Eric recalled:

We never had any choices back in those days. We was told to do what we had to do. It wasn't a good place to live. It was very difficult.

The Man Behind the Iron Sheet

Eric is well known as a proactive, passionate advocate for the preservation of local history and culture, and it was in this capacity that he first approached the National Museum about representing the story of Hollywood Mission.

Eric donated to the Museum a sheet of ripple, or corrugated, iron that was used to tell the story of missions in From Little Things Big Things Grow.

The word 'mission' is used in Aboriginal English to refer both to church missions and government-run reserves. Hollywood Mission was government-run.

The iron was originally used as building material at Hollywood and is now one of the few remaining pieces of the mission's fabric.

When the mission began to close in the early 1950s, residents started to be forcefully moved out and the corrugated iron sheets, which had comprised their homes, were reused by the remaining residents.

The sheet donated by Eric is now one of the few remaining pieces of the mission's fabric.

Homes made from this type of iron, which was used as building material on many New South Wales missions, were freezing cold in winter and baking hot in summer.

Eric Bell:

They was just the ripple iron on the outside and nothing on the inside. So what all the men used to do – well I know, I did it with my Dad – cross over into the old rubbish tip and find as much of the hessian bags as we could find and then nail them onto the walls and go down to the paddock where there was a lot of whitewash. We would then come back and paint it. And the ceiling as well to help to keep the cold out, because it gets very cold. This was on top of the hill and the wind would really blow up that hill.

During my visit, Eric used sketches and old photographs to recount his memories of how mission houses – including his own childhood home – were constructed, laid out, and enhanced by their occupants to make them more habitable.

Eric Bell:

1955 was when everybody was moved out of there. As you can see the houses started to disappear. What a lot of people did, what a lot of men did, was pull all these other houses down when they were left and use the corrugated iron or the ripple iron out of it to build on rooms because they had big extended families. Some families had eight or nine kids and there wasn't much room in a two-bedroom house.

Dangers and difficulties of growing up on a mission

Generously taking me around the boundary of the old mission site and surroundings, Eric described the dangers and difficulties of growing up on an Aboriginal mission. He pointed out the bushy area where the mission kids used to hide so that they wouldn't be taken away when government officials visited. Sadly, two of Eric's sisters were removed.

Eric pointed out the site of the old slaughter-yard and the cemetery, which sat just opposite the mission and contributed to the unpleasant conditions. He also showed the section of river that he and his cousins had to cross almost daily in the middle of winter to check if their rabbit traps had yielded anything for tea.

Eric Bell:

A lot of the women used to keep these houses really clean. They would get sandsoap or something and they would scrub those floors. It would be cleaner than this table here. But we had to, because the welfare department would come along. And they can walk into your house any time they like, the same with the equivalent of DOCS now. They could come in and they would always bring the police with them, you see, so we couldn't say anything – or the parents couldn't say anything about it because they had the police, they were protected. This is why everything was so clean.

Pleasures of life in an Aboriginal community

Apart from these difficult memories, however, Eric also recounted the pleasures of life within the close Aboriginal community, and of childhood in the local landscape.

Pointing towards the rushing river and the surrounding hills, he recounted the great times he used to have going for swims, bushwalks, exploring and hunting with other kids from the mission.

Eric recalled that when the water ran out at the mission, the women used to all go down to the river and do the washing together, while the men fished.

He also recounted how the kids always tried to 'make a bit of fun' for themselves without squabbling or resorting to vandalism.

Hollywood Mission closed in 1960 and its site has since been subdivided into four suburban blocks.

Eric Bell:

We as kids always enjoyed ourselves up there. In the winter time we didn’t go swimming of course, but we went hunting a lot – always chasing rabbits and all that kind of stuff. We’d go out along the rivers and fish, take a long hike, go to the rubbish tip. That was a good little adventure that, about four or five kilometres. And we would find something out of there that was any good, we would bring it home or play with it as a game and always play down the paddocks at night time, played on the mission, games of rounders and things like that. We all enjoyed ourselves as kids.

As a member of one of only six Aboriginal families permitted to stay in Yass after the mission closed, and as one of the last people old enough to remember life at Hollywood, Eric's memories and association with place are themselves a part of Indigenous and local history.

Eric Bell:

Well they only kept six families here. They built some houses in north Yass, six houses, and I think the reason why they let those families stay here was because the husbands were employed. They had jobs. The others, if they didn't have a husband, they were moved on to places like Cowra, Walgett – places like that, other missions. Some of the ladies told me that they were told that either you move out – one lady told me that she had to move to Cowra and that if she didn't go to Cowra they were going to take her kids off her. She didn't want to lose her kids so she went to Cowra. But I think she had a brother living there, so it made it a bit easier. She knew a lot of people and there was quite a few relatives – but, no place like home. We never had any choices back in those days. We was told to do what we had to do, you know. We had no choice.

Keeping the memory of Hollywood alive

Speaking of his contribution to the exhibition and his work in perpetuating the memory of Hollywood, Eric said:

I'm proud to be able to tell the story of Hollywood mission. It needs to be told. The area where the mission was has changed now and there are no landmarks or visual indicators that an Aboriginal mission was ever there. It is all private homes now with new landscaping. If you never lived in Hollywood Mission and didn't have those memories of living there, you would never know where the site was ... the area has changed so much.

A quote from Eric's invaluable recollections and an image provided by him were used in the exhibition to contextualise the sheet of iron which Eric donated, and to help tell the wider story of missions in Australia.

In our collection

Explore From Little Things Big Things Grow