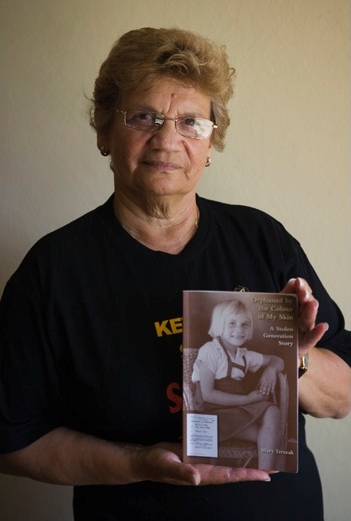

In February 2009, Museum photographer Lannon Harley and assistant curator Karolina Kilian visited Mary Terszak (nee Woods), a Nyoongah woman from south-west Western Australia.

During the visit, they recorded Mary's memories and memorabilia of institutionalisation, as well as her reflections on how being a member of the Stolen Generations has affected her life.

Mary's childhood

MARY TERSZAK: I was put into Sister Kate's in 1944 as a two year old and I left when I was 20, so I had 18 years of institutionalisation.

But first off I was born on the Moore River Native Settlement, so that's one institution, and secondly I was then moved to Carrolup Mission, and from Carrolup Mission I was put in to Sister Kate's, so that was three institutions by the age of two.

Life at Sister Kate's wasn't easy at all. It was regimental style living ...

We were just first family, really, because we knew nothing else, but as far as anybody was concerned about anybody, that didn't take place.

I mean you couldn't go in search of a mother because you didn't have one, you were told you were an orphan.

So life at Sister Kate's wasn't what I would have liked it to be, but then again I don't know any different. That was the way life was – children came in and out, people went, people came, and we didn't really take much notice of what was different for us.

We had our dormitories, we had our chores, did everything we had to do. It was a very sterile way of living.

Then from Sister Kate's I went to the home of the Good Shepherd [a reformatory] at the age of 12, returned when I was 13, and stayed till I was 20, so I had four institutions to live with till I was 20.

Most people who are 20 are going and doing their own thing and understanding the world, but we had no idea, nothing was ever explained to us about what is life, or how do we look at things in a proper way.

All we knew was how to be good housekeepers and that was the role we played because there was no intentions of education for Aboriginal people. There were the farms for the boys and the girls were domestics, and that happened right through.

I did typing when I was in the Home of the Good Shepherd and that got me away from ironing shirts all day long to the sound of the rosaries, but to be locked up in that kind of environment was terrible ... I just don't understand why I was bonded with my mother till I was two and then I had the worst situations living through institutionalisation. You didn't have any social interaction, you just stayed in an institution.

And then when I had to go out at 20, it was very frightening, cause then I was out on my own, and going to work, and then you copped the racism once you got out. We were told they [Aboriginal people] were not nice people anyway, and [we] weren't to associate with them.

How the events of Mary's childhood influenced the rest of her life

MARY TERSZAK: Talking about childhood, it was [a] numb situation, it wasn't anything to walk around and rejoice [about] or anything. Because it's like yourselves – if you live in a home, you only know what happens at home, so the life we had was something we adapted to cause that's all we know.

There is no mums and there is no dads, there's just house mothers, who can't be a substitute for a mother because these house mothers meant nothing to us – they came, they went.

You had to kneel down and say your prayers and bless the house mother before you went to sleep. We used to have to say that religiously – 'and bless the house mother' – and the people in charge of the home, and then get into bed and that was it.

But never 'good night', never, never a tuck-in. And then just 'come on, up you get', that sort of thing. Nothing. As I said, it was just sterile, the whole thing was sterile. Nothing meant anything.

We all got on alright, but no one could console each other, because no one knew how to do that. If one person cried, you didn't really do anything, cause how do you nurture someone when you don't know how to nurture someone crying?

You just say, 'Oh, don't be a big sook', or 'Oh, what are you crying about?', or something like that. And if you had the proper training, you might have been able to be sympathetic to one another about what their needs were, or what they were wanting, but you couldn't.

Childhood to me was nothing and it didn't give me anything that I could walk away with and cherish. I used to play the song called 'Nobody's child' because that's how I felt it was.

I think that's why when I had the children it was so precious to have them, you know, something of mine. John used to say 'our children' and I would say, 'No, mine', 'Yes, but they are ours' and I would say, 'No, mine' cause that was all I needed, I needed something in my life.

And I was very over-protective – didn't let them climb a tree, wouldn't let them do anything, and she [Mary's daughter] used to say to me, 'Mum, how come you could climb a tree?', and I said, 'Because no one cared, but I care, and that's why you don't.'

I was just frightened something might happen to them, you know, cause it's a pretty rough world – you can do all the right things, but something can always happen, so as long as I could protect them as long as I could, you know, and then they make their own stance and then they move on.

How institutionalisation made Mary a stronger person

MARY TERSZAK: I think you become a survivor, you have to ... I had to do that for my children. If I didn't have the children, I could be drinking and doing whatever, cause there would be no other reasons.

I mean, I drank in my young years, and I felt good because it hid my Aboriginality. I didn't worry about it then, but it was there the next morning, I can't take it away. I've said I wear my uniform every day, you know, that's who we are as a people, the Aboriginal people, you can't white wash us or do anything else.

And the strange part, I always say, is people want their tan, but it get[s] you into trouble. Why would you want a tan when it was a 'no no' for us to be tanned, you know.

And I think we learn to joke about our feelings and get on with things and you have to. If you don't have a joke and carry on, then you might as well lie down and die, cause life hasn't been that good.

But I know we have to make the most of it, so in my studies I am trying to make the most of what I can out of a bad situation. And having the children and having the grandchildren, I have a wonderful relationship with them all, and beautiful friends.

Mary's feelings about reconnecting with her family

MARY TERSZAK: It was a culture shock, the biggest culture shock I've ever had, you know. Beause I think I visualised my mother as a white person, I think, because I was told my dad was black and I thought 'she must be like me then'.

And then when I saw her, I thought 'it can't be, it's not my mother'. Because the child was looking for a pretty woman, and all this sort of thing, you know. But that wasn't to be. So that was really, that shot me down some.

And I think the hard part, too, today for me at my age, is [that] I have never, ever, said 'mum' to anybody. And you know, when I look at her, I could probably say it, but it's only making her feel happy. It's not really from the heart that I'm doing it, cause she only gave me birth.

I think they [Mary's family] was expecting everything, it was gone be a joyous time, but it wasn't, no. Because I'm perceived as being different and I know that – I dress different, I talk different, we live different, you know. But that's my upbringing and that's the white trait that I have and that overrules that Nyoongah baby.

You know, I was two years as an Aboriginal child and then all taken away. I now, as I said, stand here not as the person that I was born to be – I am a changed, programmed into the disciplines of white society.

Friendships with 'family' from Sister Kate's Children's Home

MARY TERSZAK: I think we [the children from Sister Kate's] are growing up and seeing a lot of things differently now. And I, maybe I grew up mentally too, or saw something that's different. It's like any family – there is no rule in the book that says you have [to] still love one another. You know what I mean? Families break up.

I'm still in touch with a few of them, we still have time when I go home to Perth, but, em, I think now, for me, I can live outside of sister Kate's, finally. I don't have to be living where one person tells me I have to, I can make my own decisions now.

And I've found some wonderful friends along the way who have helped me in very personal issues through my studies, a lot of things, and in that [Sister Kate's] newsletter it said I've found my own, 'Mary has met her own new family and friends', and I thought that's terrible, I am 60 odd years of age, I think I'm entitled to have my friends.

I've lived here [New South Wales] for 40 years by myself, isolated, away from everything that was close to me from a child, and to live here and feel very sad, not having any family [except for her children] to talk to or even a cup of tea, and being beaten by my partner – you know, living with domestic violence, and an alcoholic, that was terrible, I couldn't go anywhere.

Because that's a part of how I grew up – adjusting to everything. And I had to, whether I liked it or not. One would say, 'Why did you stay in that relationship?' It's because I wanted things to be a family, for the kids to have a mum and dad. But it wasn't meant to be.

Why Mary went to university and decided to study in Perth

MARY TERSZAK: It was to find myself and to go home to Nyoongah land – cause that's where I needed to go – back on my own home country, and put my feet on Nyoongah land and say 'I'm home'. And I can do this.

And it was for healing, cause I'm not a Koori, I don't belong in New South Wales, it's my country, the south-west of Western Australia, and that's where I had to learn because that's where all of my history is, in Perth.

So to go home and study at Curtin University and do it and meet all other Nyoongah people, because I had never associated with Aboriginal people for a long time. And it was good that you certainly find out you are not one orphan, you have a family as huge as this [opens arms wide].

Why Mary works with Indigenous children at a local school

MARY TERSZAK: I am just a mentor. As soon as I go into the school, I check every classroom to see if our kids are in, and if they're not I want to know why they are not here.

I have special ones who might need more reading to, but most of the time I just give a good talking and see if they are ok, if anything is bothering them. And if you're ever cranky, we'll just go and have a talk, and we can go in the big yard, and you can tell me you're feeling shitty today, that's ok mate, I'll understand that.

But you can do that with me, you don't have to do it with the other teachers, cause they don't understand where you're coming from. And it's hard because when I first went there, they were called 'nigger', 'black', you know, and I said you can put a stop to that. Not while I'm here you're not gone do that.

To do what I do for the children at the school – it's my own childhood. I am just recapturing, because I sit on the ground, on the classroom floor, when I have got the little ones with me, because I'm no different and I'm on their same level.

Because I am older doesn't mean I have to stand and be any bigger than them. I sit on the floor, and I'm back to my time at school. It's just like being a kid yourself – the kid that you should have been when you were growing up.

Importance of the Stolen Generations speaking about their experiences

MARY TERSZAK: I think it is high time Aboriginal people did have a voice. And I think that is one of the things that I learnt going to university – to be empowered. Because I think for years and years our people never talked.

We were shunned at, or 'don't speak, I am not talking to you', and those types of attitudes, so to now finally stand up and have a voice within your own country ... It's a black Australia and why weren't we given a voice to talk?

And the fears were, if you educate Aboriginal people, this country was gone be in for a bit of a shock, so that's why Aboriginal people never spoke up till we later on got people who found their voices to be activists.

Because it's the only way you can be an Aboriginal leader, an activist, and get up there and raise the awareness of the white people, and we do have the right to speak.

And to talk about the Stolen Generations is important because people think there is no Stolen Generations, they thought that it was in the 'best interest of the child'. Well, that wasn't in the best interest of myself, I know that.

And I think that for myself and for most Aboriginal people, I think that each and every one has their own stories that relate to the fact [that] it wasn't right and it should never have happened.

And why were Indigenous people taken to be with white people? It wasn't as if they were going to have their own culture still because we had a cultural genocide. In the hope that we didn't go back to our own people?

But because there is something missing in your heart, you have got to find out who you belong to. And that goes for any child, irrespective of colour or whatever – they have to find out who they belong to.

So when we find out who we belong to, it's heart-breaking but it also gives us a chance to talk about it and not feel shamed that we do have a voice to be able to talk about what's happened in this country.

In other countries it's known – we learnt about how it was for the Jewish people, which was [the] dreadful Holocaust. We learnt about that, yet we didn't learn about our own backyard, what the history was. So we need to all now stand up, say what it is and be acknowledged as it was for Sorry [Day] – we were acknowledged, at last, as people.

And to me, I think it gives the greatest feeling for people to be aware and understand because they don't really know. They say, 'Oh, we weren't taught this at school, we never learnt about that,' and I say, 'Well, that's why I did my degree.' We had to find out our background and to stay proud now and say it, even though it hurts, it hurts.

But at least I am giving to people a bit of knowledge about what it's all about and hopefully they can walk away and understand that it is happening, it has happened, and we will never ever go back and do it again.

Explore From Little Things Big Things Grow