Freewheeling: Cycling in Australia explored the history of cycling through the Museum’s collection of bikes, trophies and riding gear.

Freewheeling was on show at the National Museum of Australia from 13 April to 9 July 2017.

The first bicycles arrived in the colonies in the 1860s and Australians were quick to embrace this new technology. French-designed velocipedes were the first human-powered wheeled machines here. Typically built with 2 or 3 wheels shod in iron or wood, these machines had no brakes or gears.

The first bicycle race in Australia is believed to have taken place at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in 1869, although some claim velocipedes were ridden in contests in Sydney two years earlier.

The high-wheeler, known later as the penny-farthing, arrived in Melbourne in 1875. They soon confirmed the speed, excitement and potential of the bicycle. High-wheelers featured rubber ‘cushion’ tyres, so were more comfortable than velocipedes, but were still difficult to manage. Riders sat more than 2-and-a-half metres off the ground. A fit cyclist could sustain speeds of between 16 and 25 kilometres an hour.

By the late 1890s the 'safety' bicycle offered people a cheaper and more comfortable ride and the cycling craze had taken hold. Riding schools and touring clubs formed and cycle racing became a big business.

Women have been captivated by cycling since bicycles arrived in Australia. The bike was a catalyst for emancipation as women enjoyed new independence and freedom.

An early record-breaker was Billie Samuels, a diminutive 23-year-old Victorian, who in 1934 set the women’s record for riding from Melbourne to Sydney when she completed the journey in 3 days and 17 hours. A few months later, Samuels turned around and rode from Sydney to Melbourne, breaking Elsa Barbour’s 1932 record of 3 days and 7 hours.

Another Australian cycling champion, Anna Meares started competitive cycling in 1994 at the age of 11. At 21 she joined the Australian Institute of Sport’s track cycling program and became one of Australia’s most successful cyclists. Now retired, Meares achieved multiple world championship victories, and is a national and Commonwealth, world and Olympic record holder.

Today, Australian women continue to take up cycling in increasing numbers, although professionals receive a disproportionately small share of funding.

Bicycles designed for children were developed soon after the invention of the safety bicycle in the 1880s, but for many decades they were not mass-produced in Australia. Children rode tricycles and adult bikes until the 1950s, when bicycles came to be seen more as a child’s toy or a way for young people to get around.

In the decades after the bicycle arrived in Australia, cycling competitions became big business. Talented riders including Hubert Opperman and Ken Ross abandoned their amateur status to vie for cash prizes in major competitions in Australia and overseas.

Cycling's popularity declined in the mid-20th century, but underwent a major resurgence from the 1980s, with government funding for high-performance programs.

Australians continue to perform well in the Tour de France, with yellow jersey wearers including Phil Anderson (1981), Stuart O’Grady (1998 and 2001), Bradley McGee (2003), Robbie McEwen (2004), Cadel Evans (2008, 2010 and 2011), Simon Gerrans (2013), Rohan Dennis (2015), Jai Hindley (2023).

Australia's first Olympic cycling medal was won by Dunc Grey and the Museum's collection includes a UCI World Championship medal won by Sue Powell. Sue, a multiple world champion medallist, also won gold in the 3-kilometre individual pursuit (C4 classification) and silver in the road race at the 2012 Paralympics.

Getting out of town to explore the bush has always been part of cycling in Australia. Early riders tackled many different surfaces and as the numbers of cars increased from the 1950s, cyclists became more determined to go 'off-road'. Mountain bikes reached Australia in the early 1980s and quickly became popular with a new generation of cyclists.

The first cycle races in Australia were novelty events at athletics carnivals. By the 1880s newly formed cycling clubs were organising meets and by the early 20th century, competitive cycling clubs with track and road racing programs, had formed across the country.

Earlier divisions between amateur and professional riders have eroded over time and in 2017 there were about 200 cycling clubs in Australia, with nearly 50,000 members.

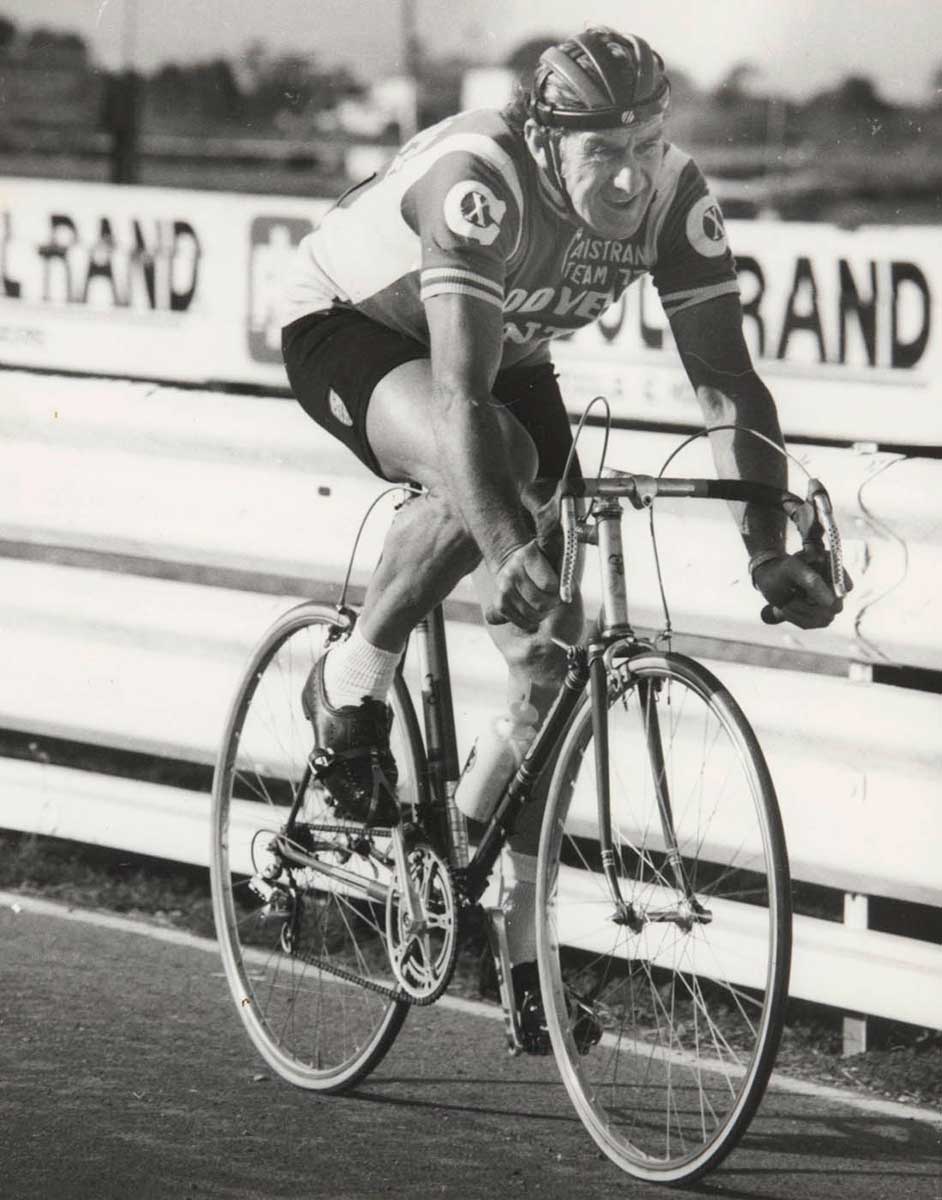

Freewheeling featured the story of amateur cyclist Jim Coyle, who enjoyed his greatest success as a veteran after a comeback from retirement. He won the Australian and Victorian road racing titles several times during the 1970s and 1980s.

Since the 1870s, generations of bicycle-riding explorers, adventurers and athletes have tested their wills, bodies and machines against the vast distances of the Australian continent. Some have pushed themselves to the limit for glory, some to earn sponsorship dollars, and others simply because they wanted to get from one place to another.

As the number of bicycles increased during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Australians took up touring, rambling from town to town on leisurely longer rides. Cycle touring declined in popularity after the Second World War, as many people started travelling in cars.

By the 1980s, however, long-distance recreational rides made a comeback through mass participation events and randonneuring, a non-competitive sport in which cyclists aim to complete a set course within a specified time limit.

Freewheeling told the story of Hubert Opperman, one of Australia's most successful long-distance cyclists, and an international cycling celebrity after his performance in the 1928 Tour de France. The exhibition also profiled a more contemporary record breaker, Peter Heal.

- Last updated: 21 February 2015

- 3 programs