Transit of venus

The phrase 'transit of Venus' refers to the passage of the planet Venus across the face of the sun, as seen from Earth. Such transits occur in pairs 8 years apart, with an interval of over 100 years between the pairs.

In 1677 the English astronomer and mathematician Edmund Halley, drawing upon the work of mathematician James Gregory, proposed that an accurate measurement of the time it took for Venus to cross the sun would provide a measurement for the distance of Earth from the sun (known as the astronomical unit, or AU), and thus allow for an accurate determination of the size of the solar system.

Halley worked out that the next transit would occur in 1761, by which time he might reasonably expect to be dead. In 1716 he read his famous 'Admonition' paper to the Fellows of the Royal Society.

It set out the importance of organising expeditions to observe each transit from a number of locations around the world and described the calculations necessary for determining Earth's distance from the sun. This paper was published that same year in volume 29 of the Philosophical Transactions.

Orrery demonstrating the transit of Venus

The first object in this section was a model of the transit of Venus dated to about 1760 and made by Benjamin Cole of London.

The model is a mechanical planetarium, or orrery, and was built to demonstrate the principles of the transit of Venus. The model is not to scale, but shows the essential relationships between Earth, Venus and the sun for the period of the transit. Turning the handle causes Venus to pass across the face of the sun, while Earth rotates about its axis. The slanting line inscribed around Earth indicates the southern limit of potential observation sites, while the clock face below shows the transit duration.

The time taken for the transit – over six hours when viewed from Tahiti – was a major factor in the selection of sites from which observations would be made. This model was donated to the Royal Society by one of its Fellows, John Boyle, 5th Earl of Orrery and Cork.

Despite extensive preparations, the observations taken of the transit of Venus in 1761 proved inconclusive. Poor weather conditions hampered the taking of observations in many places, and in some locations the sun had set before observations of the transit could be completed.

The Royal Society therefore resolved to make the most of the transit expected on 3 June 1769 by sending out an expedition to observe it from the South Seas, where the six-hour transit would fall during the middle of the day. The cost of mounting such an expedition was beyond the Society's resources, so it approached King George III for financial assistance in February 1768.

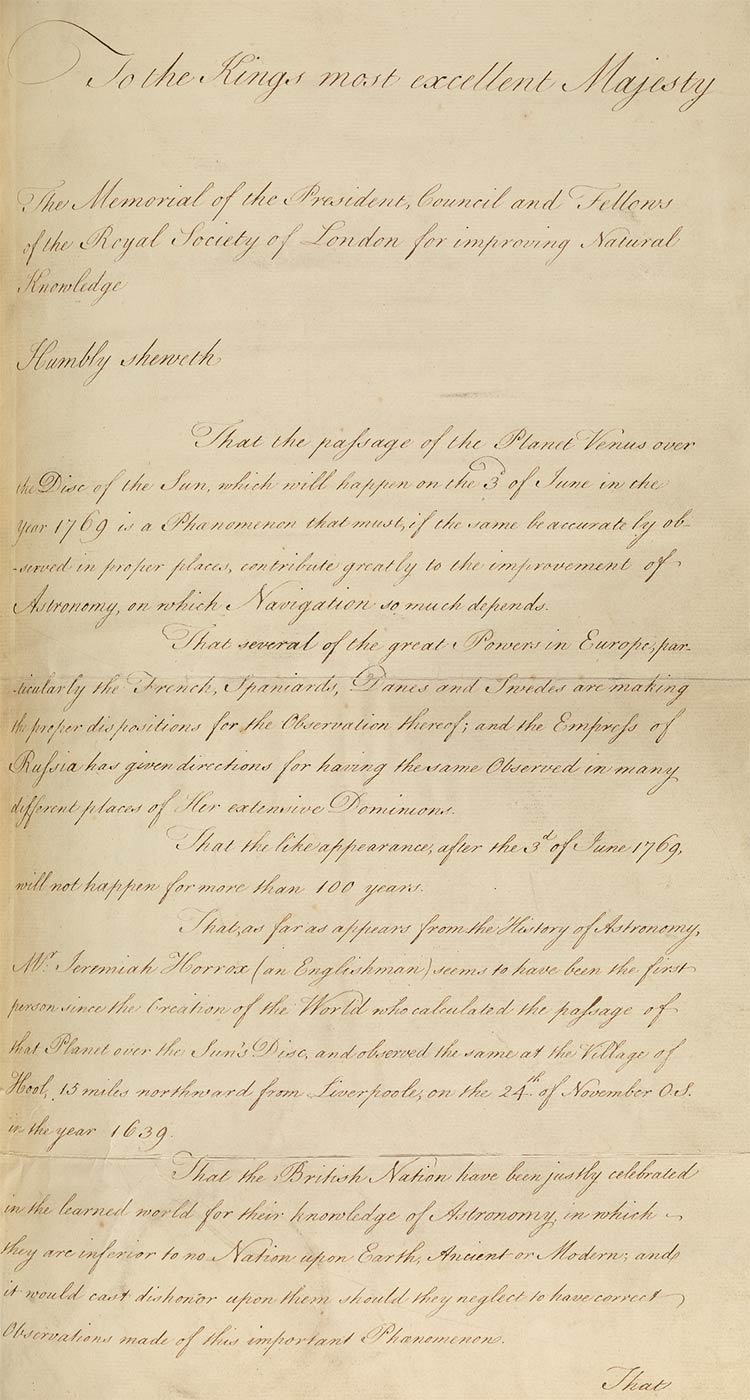

Memorial presented to King George III by the Royal Society

The Fellows' petition, titled 'Memorial presented to King George III by the Royal Society requesting financial assistance to undertake an observation of the transit of Venus from an island in the South Seas', stresses the significant advantages to navigation that would arise from an increased knowledge of astronomy, and concludes with an appeal to national pride:

The British Nation have been justly celebrated in the learned world for their knowledge of Astronomy in which they are inferior to no Nation upon Earth, Ancient or Modern; and it would cast dishonour upon them should they neglect to have correct Observations made of this important Phenomenon.

Under diplomatic pressure from Spain, which was once more asserting its customary 'ownership' of the Pacific, as bestowed by Pope Alexander VI in the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), George III was happy to have the 'purely scientific' excuse the petition supplied for a venture into the South Seas.

The king gave his assent to the petition within a week: not only did he agree to underwrite the costs of the voyage and to provide funds to cover the salaries and expenses of the astronomers, as requested, he also made available a Royal Navy ship, with officers and crew, and fully provisioned with victuals and stores.

Joseph Banks, a wealthy gentleman botanist, was permitted to join the voyage; he spent an estimated £10,000 of his own money (more than the amount spent by the Crown) hiring and equipping the civilian scientific party that accompanied him.

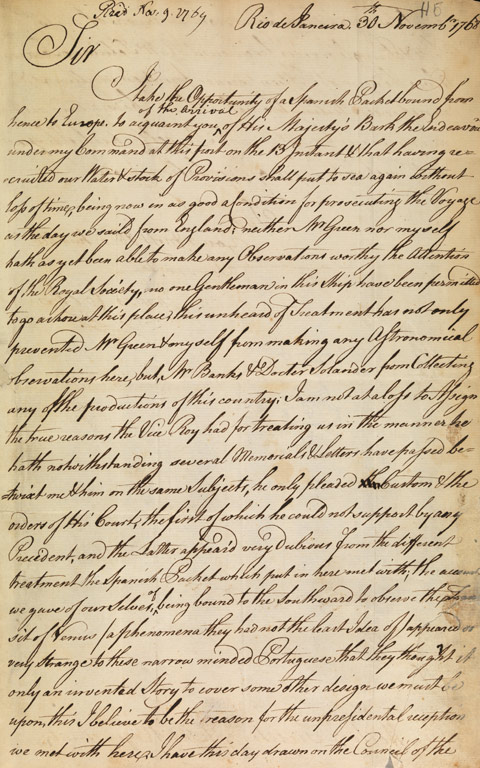

Letter from James Cook to Charles Morton

The visitor came next to a letter from James Cook, Rio de Janeiro, to Charles Morton, Secretary of the Royal Society, dated 30 November 1768.

Cook's letter informed the Royal Society of the poor treatment those on board the Endeavour had received from the Portuguese viceroy at Rio de Janeiro.

The viceroy refused to believe that the British king would have sent a ship to the South Seas on such a fool's errand as the observation of an eclipse and concluded that the Endeavour's real purpose was smuggling or piracy.

In the letter, Cook explains to the Secretary of the Royal Society that:

neither Mr Green nor myself hath as yet been able to make any Observations worthy of the Attention of the Royal Society, no one Gentleman in this ship have been permitted to go ashore at this place

He also informed the Fellows that he had expended £15/14/9 on their account. Banks, having been prevented from collecting his botanical specimens, also roundly criticised the viceroy in his letters, using much less temperate language that probably reflected the feelings of all on board. Pointing out the pitiful state of the Portuguese defences, he urged the Royal Navy to avenge this insult by sending ships to Rio de Janeiro to bombard the port into submission.

Letter from Lieutenant James Cook, Rio de Janeiro, to Charles Morton, Secretary of the Royal Society, 30 November 1768.

Sir

I take the opportunity of a Spanish Packet bound from hence to Europe, to acquaint you of the Arrival of His Majesty's Bark the Endeavour under my Command at this port on the 13 Instant & that having recruited our Water & stock of Provisions shall put to sea again without loss of time, being now in as good a condition for prosecuting the voyage as the day we sailed from England; neither Mr Green nor myself hath as yet been able to make any Observations worthy of the Attention of the Royal Society, no one Gentleman in this Ship have been permitted to go ashore at this place, this unheard of treatment has not only prevented Mr Green & myself from making any Astronomical observations here, but, Mr Banks and Doctor Solander from Collecting any of the productions of this country; I am not at a loss to Assign the true reason the Vice Roy had for treating us in the manner he hath not withstanding several Memorials & Letters have passed betwixt me & him on the same subjects, he only pleaded Custom & the orders of His Court, the first of which he could not support by any Precedent, and the latter appear'd very dubious from the different treatment the Spanish Packet which put in here met with; the account we gave of our Selves, of being bound to the Southward to observe the Transit of Venus / a phenomenon they had not the least Idea of / appeared so very strange to these narrow minded Portuguese that they thought it only an invented Story to cover some other design we must be upon, this I believe to be the reason for the unpresidential reception we met with here & I have this day drawn on the Council of the

[new page]

Royal Society at thirty days sight in favour of Messrs. Scott & Pringle an order for account of Mr Feliciano Teixira Alves the sum of Fifteen pounds fourteen shillings and ninepence Sterling the value there of being laid out in necessaries for Mr Green and Myself which I hope will meet with their approbation I am Sir Your most obedt, humble Servant

James Cook

I am not at a loss to Assign the true reason the Vice Roy had for treating us in the manner he hath ... he only pleaded Custom & the orders of His Court, the first of which he could not support by any Precedent, and the latter appear'd very dubious from the different treatment the Spanish Packet which put in here met with; the account we gave of our Selves, of being bound to the Southward to observe the Transit of Venus [—] a phenomenon they had not the least Idea of [—] appeared so very strange to these narrow minded Portuguese that they thought it only an invented Story to cover some other design we must be upon, this I believe to be the reason for the unpresidential reception we met with here. (Extract)

12-inch astronomical quadrant made by John Bird

A 12-inch astronomical quadrant, by John Bird, used in the transit of Venus observations, was also featured in the exhibition.

The quadrant was intended for use in establishing the latitude and to assist in the calculation of the longitude of Point Venus, Tahiti, where the transit observations were made. It was kept in a tent erected as a portable observatory, itself surrounded by a palisade constructed by the British on Point Venus, at one end of Matavai Bay. A guard stood outside the tent at all times.

Despite these precautions, the quadrant was stolen and Banks (whose command of the Tahitian language and close relationships with the district's chiefs gave him the capacity to negotiate) set off to secure its return.

When the quadrant was finally given back, it had suffered some damage. Fortunately, Herman Spöring, who served as clerk, assistant naturalist, artist and personal secretary to Banks on the expedition, was also a trained watchmaker. He carried with him a set of watchmaking tools and so was able to repair the instrument in time for the transit observation.

Four-pounder cannon from HMB Endeavour, about 1745

A key object included in the exhibition, the Endeavour cannon, is one of the treasures of the Museum's own National Historical Collection.

The cannon was one of six jettisoned by Cook to lighten the Endeavour after it ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef in 1770. Nearly 200 years later a team sponsored by the American Academy of Natural Sciences recovered all six cannon and other ballast from the waters off the north Queensland coast.

The inclusion of one of these cannon here makes the link between the scientific imperative to record the transit of Venus and the British Admiralty's desire that the Cook expedition should explore southern waters and document unknown territories and lands.

And so, after he left Tahiti, Cook ventured south, in accordance with his secret instructions to search for the Great South Land, and circumnavigated New Zealand before sailing east and encountering the Australian continent near what is now known as Point Hicks, on the eastern coast of Victoria.

Plates from Banks’ Florilegium

Three plates from the Museum's own set of the Banks' Florilegium, printed and hand-coloured in a limited edition in 1980–90 by Alecto Historical Editions, in association with the British Museum, were also displayed.

These beautiful illustrations are material reminders of the central role science played in the Cook expedition; more particularly, they remind us of Banks' extraordinary commitment to natural science and ethnographic collecting over the course of the Endeavour's voyage.

He and other members of his scientific party, such as fellow naturalist Daniel Solander, collected thousands of botanical specimens, many of which served as models for Sydney Parkinson's fine watercolours, from which the print plates for the Banks' Florilegium were created.

EXPLORE MORE ON EXPLORATION AND ENDEAVOUR

You may also like