Voyages of the Resolution

Although the observation of the transit of Venus did not provide the clear results that had been hoped for (owing to the phenomenon known as 'black drop effect', which made it difficult to determine the exact moment at which Venus began to cross the edge of the sun), Cook's expedition was a great success.

Two ships were chosen for this second Cook expedition of 1772–75, a precaution warranted by the Endeavour's near destruction on the Great Barrier Reef in June 1770. The ships were named HMS Resolution and HMS Adventure. Cook was captain of the Resolution, the larger and faster ship of the two, and Tobias Furneaux, who had been on the voyage that discovered Tahiti in 1767, was captain of the Adventure.

It had also been Banks' intention to return to the Pacific in the Resolution, and he paid for considerable additions to the ship's accommodations. When these works were found to have made the ship unseaworthy, they were summarily removed and although Banks protested to the First Lord of the Admiralty, and even to the king, they were not restored. Banks withdrew from the voyage, and Johann Reinhold Forster and his son Georg were given the role of 'Scientific Gentlemen' on board the Resolution instead.

The extensive natural history and ethnographic collections gathered by Banks' party, the useful maps, charts, views and drawings that had been created, the scientific readings and accurate calculations of longitude for many parts of the Pacific, and the new territories claimed for Britain – all these successes provided powerful arguments for a speedy return voyage to the South Seas.

Cook appended an argument (and even an itinerary) for just such a voyage to his Endeavour journal before handing it over to the Admiralty on his return in 1771. The program he outlined – to finally resolve whether the Great South Land of legend actually existed – became the principal aim of the next voyage, but the opportunity to test the effectiveness of chronometers in establishing longitude was also pursued.

Regulator carried by Cook on the Resolution

The long-case astronomical regulator, made by John Shelton, that featured in the exhibition was carried by Cook aboard the Resolution on both his second and third voyages to the South Seas. Regulators were accurate clocks used specifically for timing astronomical events, such as transit observations, to the exact second; this regulator is one of five created by Shelton for the Royal Society for the purpose of timing the transits of Venus in 1761 and 1769.

The regulator measures sidereal time (time measured from the apparent movement of the stars) instead of solar time (time measured from the apparent movement of the sun). In 1828 this regulator was used to compare the strength of gravity at both the top and bottom of a mine in an attempt to find the density of the Earth.

While the regulator was extremely accurate, it could only be used on land. Until John Harrison produced his chronometer H4 in 1759, no simple and effective method existed for accurately calculating longitude at sea. (H4 was the fourth model Harrison created in his pursuit of £20,000 prize offered by the Board of Longitude for an accurate method of keeping time at sea.) In the absence of accurate readings of longitude, maps were inaccurate, ships were wrecked and lives were lost.

The nautical tables provided in 1767 by Nevil Maskelyne, Astronomer Royal, Fellow of the Royal Society and member of the Board of Longitude, had been used by Cook to perform the mathematically complicated but effective method of calculating longitude based on lunar distances during the Endeavour voyage, and his maps of the South Seas were much more useful as a result.

Chronometers used on Cook's second voyage to the Pacific

H4 had undergone sea trials in 1761 and been awarded an interim prize of £2500 by the Board of Longitude, but the Board demanded further tests. Larcum Kendall, a British clockmaker, was commissioned by the Board to create a copy of H4, and astronomer William Wales was appointed to oversee the trial of Kendall's chronometer, known as K1, aboard the Resolution. The timepiece passed with flying colours.

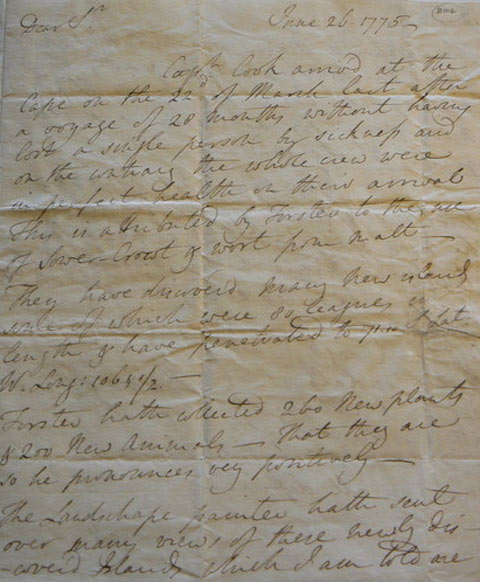

Letter from Daines Barrington to Dr Charles Blagden

Particularly fascinating for its glimpse of relations between the Royal Society's Fellows is the letter from Daines Barrington to Dr Charles Blagden, dated 26 June 1775.

Barrington's letter informed Blagden – a Fellow and later Secretary of the Society – of news he had just received of Cook's arrival at the Cape of Good Hope on 22 March, noting that in a voyage of 28 months not a single person had been lost to sickness, many new islands had been discovered, and 260 new plants and 200 new animals had been collected.

The letter mentions the work of the expedition's landscape painter, William Hodges, as masterly, and provides possibly the first record of Cook's attitude to Omai, a young Polynesian man who had accompanied the Adventure on its return to Britain in 1774.

Barrington tells us that Cook considered Omai to be 'a very great blackguard' (a term used to denote his low social status) and advises Blagden not to disclose this particular detail to 'his patient', Joseph Banks, for fear that Banks might call Cook out to a duel. In a postscript, Barrington, who was also a Fellow of the Society, added that Cook had found Kendall's watch (K1), together with the lunar tables, to be a 'most faithful guide' during the voyage.

The breathless tone of Barrington’s letter to Blagden conveys the excitement and expectation with which the arrival of the Resolution was greeted, and the voyage’s successes ensured that a third expedition would proceed, this time to investigate whether a navigable passage existed at high northern latitudes between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

Such a passage, if it existed, would greatly facilitate trade, and so, in 1776, Captain Cook sailed once more for the Pacific in the Resolution to resolve yet another major geographical question. This time he was accompanied by the Discovery under Captain Charles Clarke. The third voyage had the additional purpose of returning Omai to the Pacific.

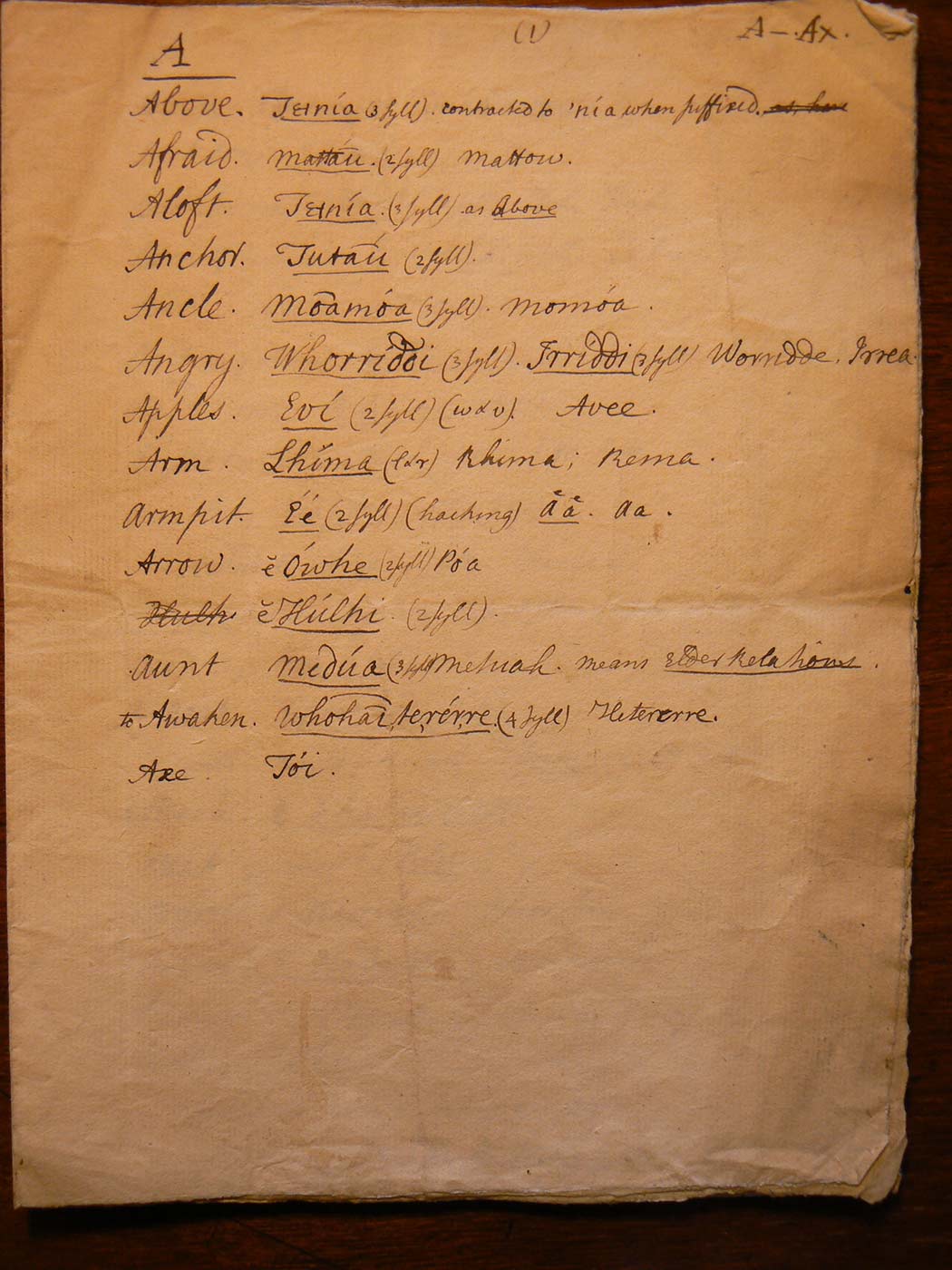

Tahitian–English dictionary

Next to Barrington’s letter was a Tahitian–English dictionary. Found in the papers of Sir Charles Blagden (although he may not have compiled it), the dictionary consists of an unbound sheaf of 20 sheets of paper, each folded in half to create 40 ‘pages’. It lists words in English followed by the equivalent in Tahitian, with pronunciation stresses indicated.

Additional papers relating to the dictionary, which may be the rough notes from which a clean copy was drawn, contain the phrase ‘Omai taiomaitai no Asoso’, which translates as ‘Omai friend good of Asoso’.

Asoso was the name Omai gave Surgeon William Anderson, whom he met on Cook’s second voyage and travelled back to the Pacific with on the third voyage.

Magnifying glass about 1770s

The last item in this section is Captain Cook's magnifying glass, another object drawn from the Museum's National Historical Collection. It was purchased at auction in 2006 and had once belonged to William Bayly, the astronomer on the Adventure during the second voyage, and on the Discovery and then on the Resolution during the third.

Bayly bequeathed the magnifying glass to his 'pupil, friend and executor' Mark Beaufoy. Many years later Beaufoy's son purchased a silver reliquary to hold it; he inscribed the lid with various details, noting that the magnifying glass had been given to Bayly by Cook.

Bayly may have acquired the magnifying glass at the sale of Cook's personal possessions that was held by his shipmates after his death in Hawaii on 14 February 1779. Or it may have originally belonged to Omai, who was given a magnifying glass at a Royal Society dinner in 1776. He may have presented it to Cook or another of his friends on board the Resolution when he left the ship at Huahine in 1777.

You may also like