Letter from James Cook to Sir John Pringle

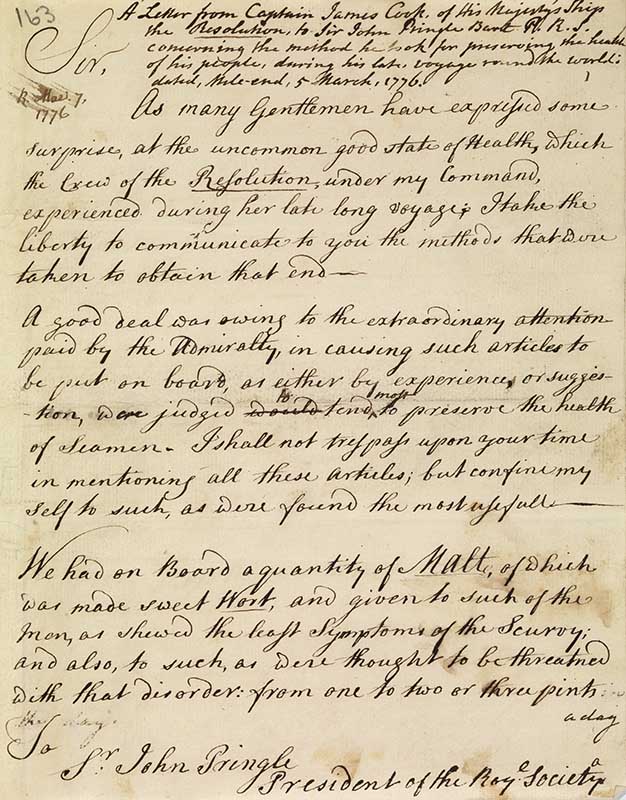

The section of the exhibition that examines Cook's role as a Fellow of the Royal Society began with a six-page letter, titled 'How health was kept aboard the Resolution', written by James Cook at his house at Mile End and sent to then President of the Royal Society, Sir John Pringle. The letter was read at the Society's meeting of 7 March 1776.

The advances made in preserving the health of those on board the Endeavour during Cook's first Pacific voyage had been overshadowed by the terrible death toll caused by fevers contracted at Batavia (Jakarta) after the ship left Australian waters.

On the second voyage, however, Cook was able to perfect the methods he had experimented with on the first, and despite months spent circumnavigating the globe in Antarctic waters, out of sight of land and lacking fresh supplies of fruit and vegetables, none of his crew died of scurvy.

Letter from James Cook to Sir John Pringle (extract):

As many gentlemen have expressed some surprise at the uncommon good state of health which the crew of the Resolution, under my command, experienced during her late voyage; I take the liberty to communicate to you the methods that were taken to obtain that end.

At this time, scurvy was a terrible scourge for society generally and for those at sea in particular. The various methods Cook employed to maintain the health of seafarers fill the letter, but he was careful to give first mention to 'wort of malt' – a remedy promoted by Pringle in his own publications (but one which contains no vitamin C).

Reading Cook's letter carefully, it is clear that he found ways to get his crew to eat fresh fruit, vegetables and meat at every opportunity. The letter was subsequently published in volume 66 of the Philosophical Transactions, but Pringle has been accused of 'editing' the published letter in such a way as to emphasise the wort of malt remedy, rather than the others outlined by Cook.

In 1776 Cook was awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society for his success in avoiding outbreaks of scurvy among his crew during the arduous 1772–75 Pacific voyage.

James Cook's Royal Society election certificate

A visitor to the exhibition could then view James Cook's Royal Society election certificate. In November 1775, Cook was proposed for membership with the following recommendation:

Election certificate of James Cook:

Captain James Cook of Mile-end, a gentleman skilfull in astronomy, & the successful conductor of two important voyages for the discovery of unknown countries, by which geography & natural history have been greatly advantaged and improved, being desirous of the honour of becoming a member of this Society, we whose names are underwritten, do, from our personal knowledge testify, that we believe him deserving of such honour, and that he will become a worthy & useful member.

This statement was read at the meeting held of 23 November 1775, and was made available at 10 subsequent meetings for those supporting Cook's proposed membership to sign.

Twenty-five Fellows did so: Joseph Banks, Daniel Solander, Baron Mulgrave, Seaforth, Charles Blagden, Charles Morton, Henry Cavendish, J Cuthbert, John Hunter, James Burrow, J Lloyd, Nevil Maskelyne, Anto. Shepherd, Matt Raper, S Horsley, John Reinhold Forster, Jno Campbell, James Stuart, Daniel Wray, Philip Stephens, Jno Ibbetson, Alex Aubert, Robert Mylne, Edward Poore and Mat Duane. Cook was elected on 7 March 1776, the day on which his letter was read to the Royal Society.

Portrait miniature of James Cook

Also on display was a portrait miniature of James Cook, rendered on ivory and mounted in an ebonised frame; this was based on the larger oil portrait of Cook that Banks commissioned from Nathaniel Dance in 1776.

The oil portrait hung in Banks' house until his death and is now in the collection of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

It shows Cook, seated at a desk in his dress uniform, examining the map of the Pacific to which he contributed so significantly. The portrait was subsequently engraved many times by a variety of artists and became the authoritative portrait of Cook.

Most reproductions, like this one, emphasise Cook's stern features, but if you look closely the original actually shows Cook smiling. The miniature is a reminder of the close and important relationship between Banks and Cook.

Banks may have been at the dinner party where Cook declared his wish to command a third Pacific voyage, in preference to taking up an appointment at Greenwich Hospital. His subsequent death on the voyage heightened the grief of those who felt responsible for sending him to sea again. Certainly, Banks used his position as President of the Royal Society from 1778–1820 to memorialise Cook and build upon his celebrity.

Royal Society Cook Medal and Papers

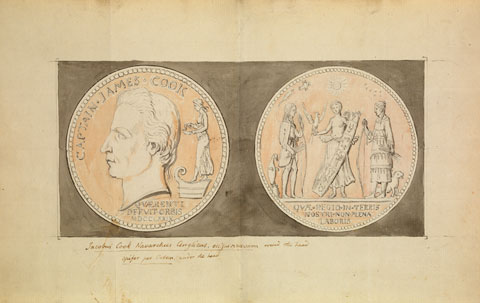

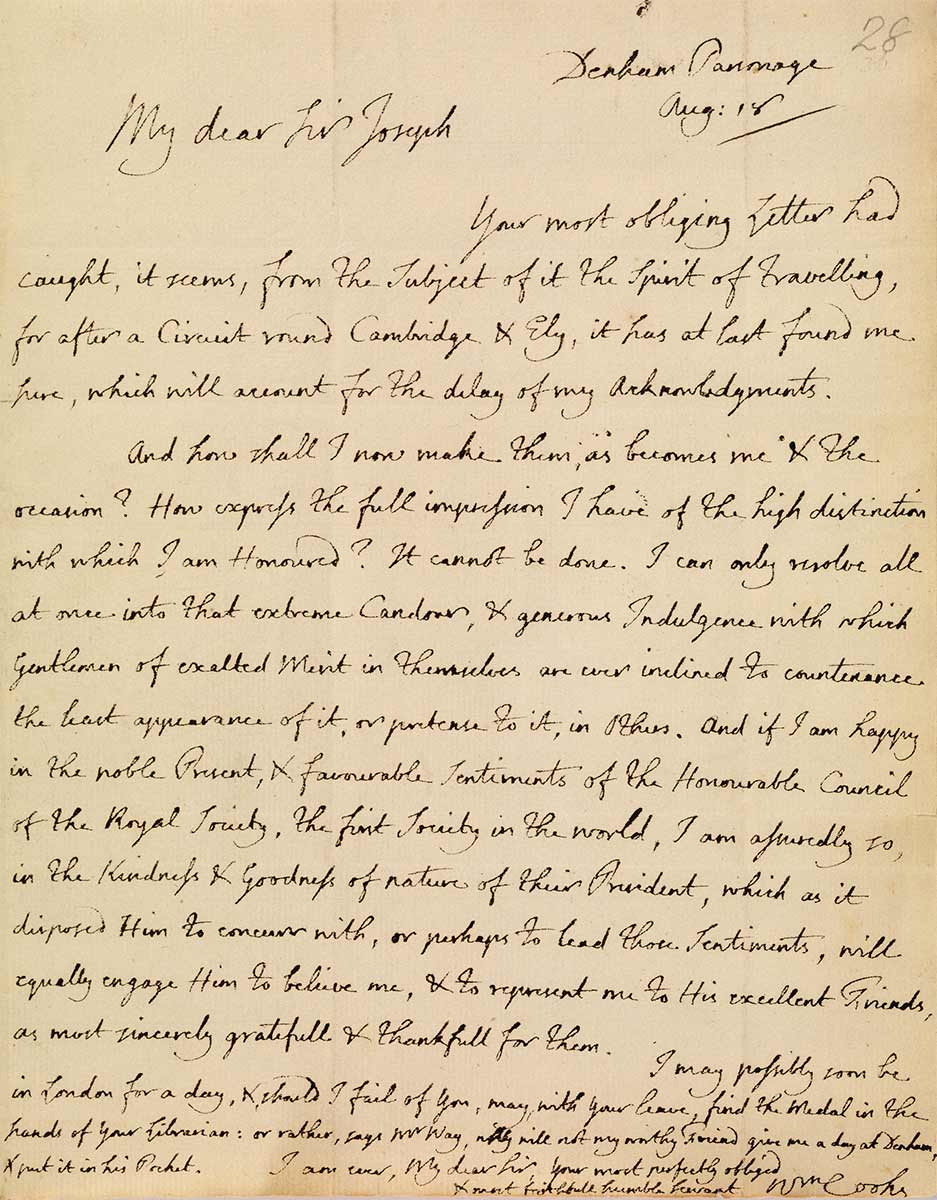

Examples from the Royal Society Cook Medal Papers 1784–85, including designs for the commemorative medal that Lewis Pingo later produced, and a letter from Eliza Cook to Sir Joseph Banks, dated 1784, were also displayed with the Royal Society's copy of the bronzed copper medal.

The medal features on its obverse a profile portrait bust of Cook in uniform, and on the reverse, Fortune (sometimes identified as Britannia), leaning upon a column with a spear in the crook of her arm and holding a rudder on a globe. The decision to create the medal was made by the governing Council of the Royal Society shortly after news of Cook's death in Hawaii reached London on 10 January 1780.

At their next meeting on January 27, the Council decided that a medal, 'expressive of his deserts', would be an appropriate memorial to Cook.

To lessen the financial burden on the Royal Society, a voluntary subscription was opened (but to members only). This was the first, and so far the only, time that the Royal Society has decided to commemorate the death of one of its Fellows in this way.

At its meeting on 17 February 1780, the Council decided that the medal would be struck in different metals, with subscription rates set at 20 guineas for a gold medal and 1 guinea for a silver medal or two bronzed ones, and that each member would receive a free bronzed medal, in addition to any others he had subscribed for. Banks headed the list of subscribers, putting in an order for one gold, 23 silver and 13 bronzed medals. In all, it seems that 22 gold, 322 silver and 577 bronzed medals were created.

Ten days later, the Council resolved:

that it is the opinion of the Council that the very signal services performed by the late Capt. Cook – a very worthy member of this Society in the many and extensive Discoveries he has made in different parts of the Globe merit some public act on the part of the Society as a mark of the high sense they entertain of the importance of those services and to testify to their Zeal for perpetuating the memory of so valuable and eminent a man.

References

Philosophical Transactions, vol. 66, pp. 402–06.

Election certificate of James Cook, EC/1775/27.

Quoted in Richard L Smith, Royal Society Cook Medal, Wedgwood Press, Sydney, 1982, p. 6.

You may also like