We continue to revisit and rethink James Cook’s 1770 encounter with Australia. As time passes, our stories change.

We asked what does the Endeavour’s voyage represent in 2020 — for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. See recent artworks created by Indigenous communities and school children and Cook memorabilia and souvenirs created over many years.

Which Cook do we see?

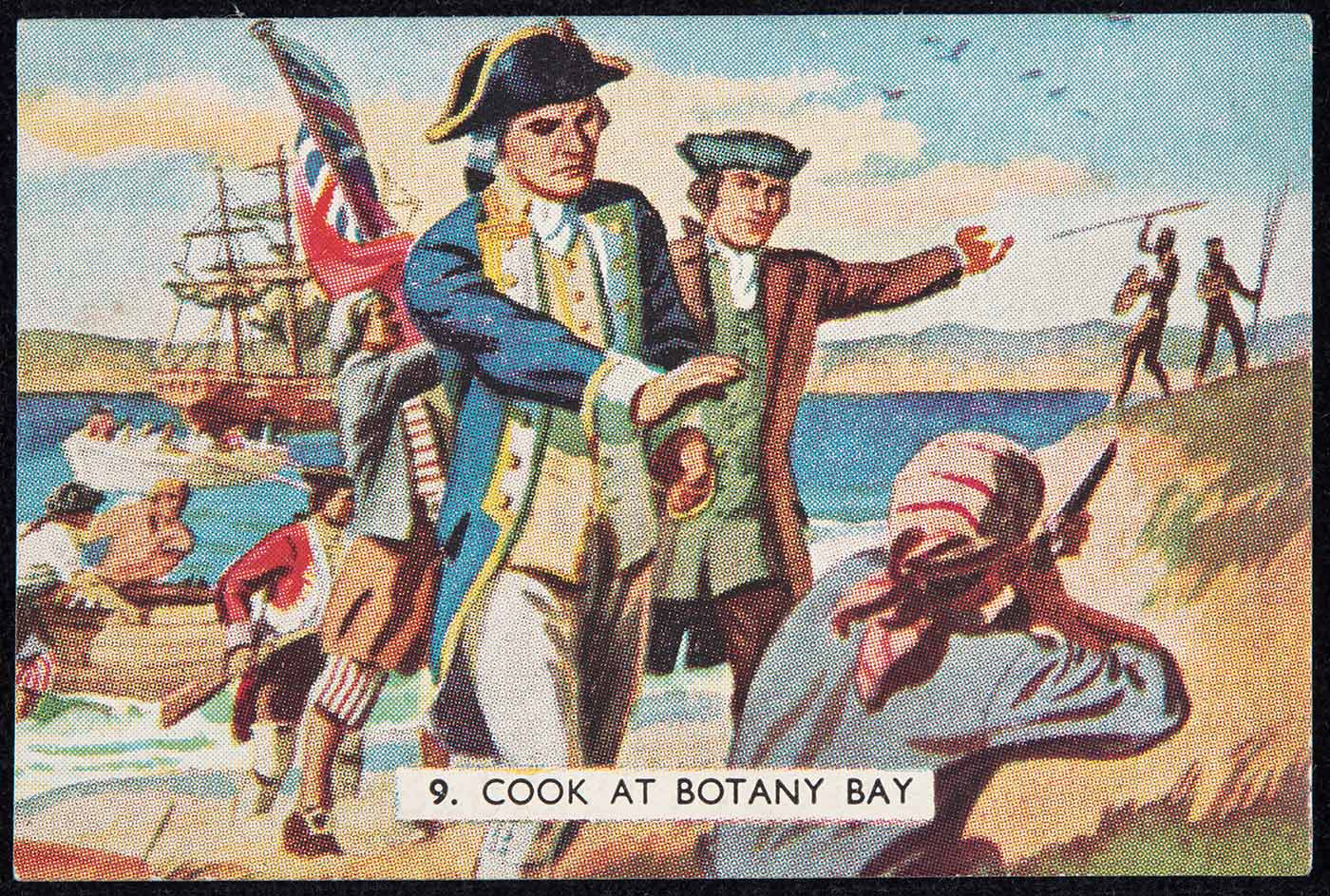

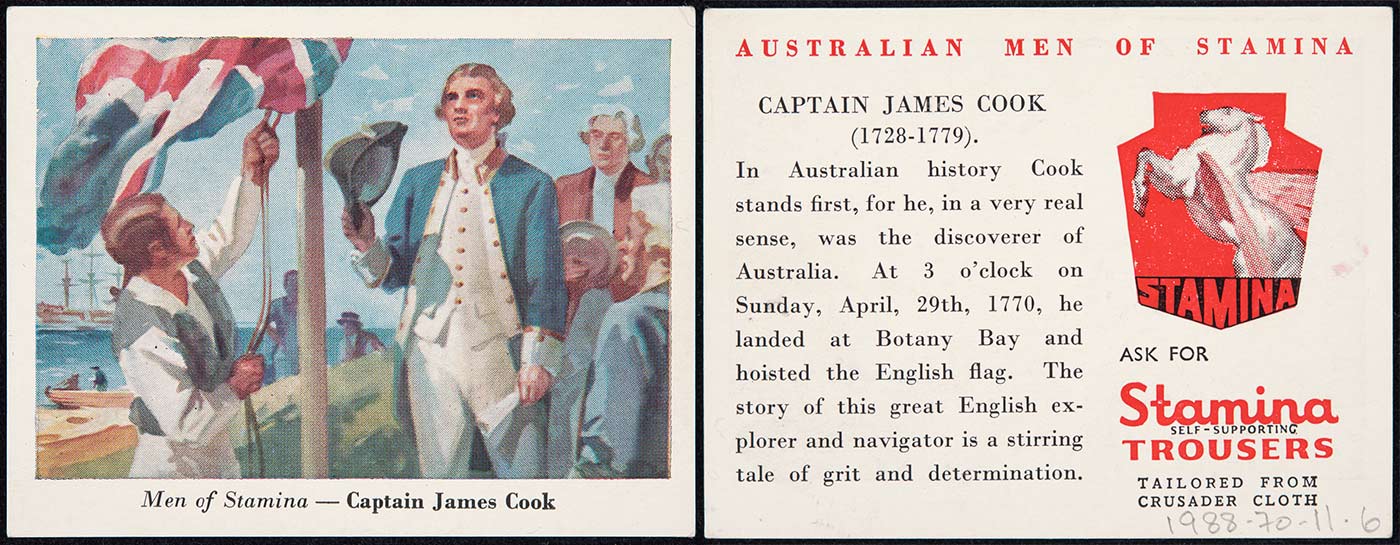

A 1952 swap card and Vincent Namatjira’s Cook portrait offer contrasting views on what Cook represents. As a ‘man of stamina’, Cook is the discoverer of Australia and his achievements are cast as a ‘stirring tale of grit and determination’. The card shows him gazing up at the British flag that he has just planted on Possession Island.

By contrast, Namatjira reimagines Cook seeing new things — things that he missed in 1770. He looks across the water, seeing into the very heart of Australia — red earth and ghost gums.

Retaking possession

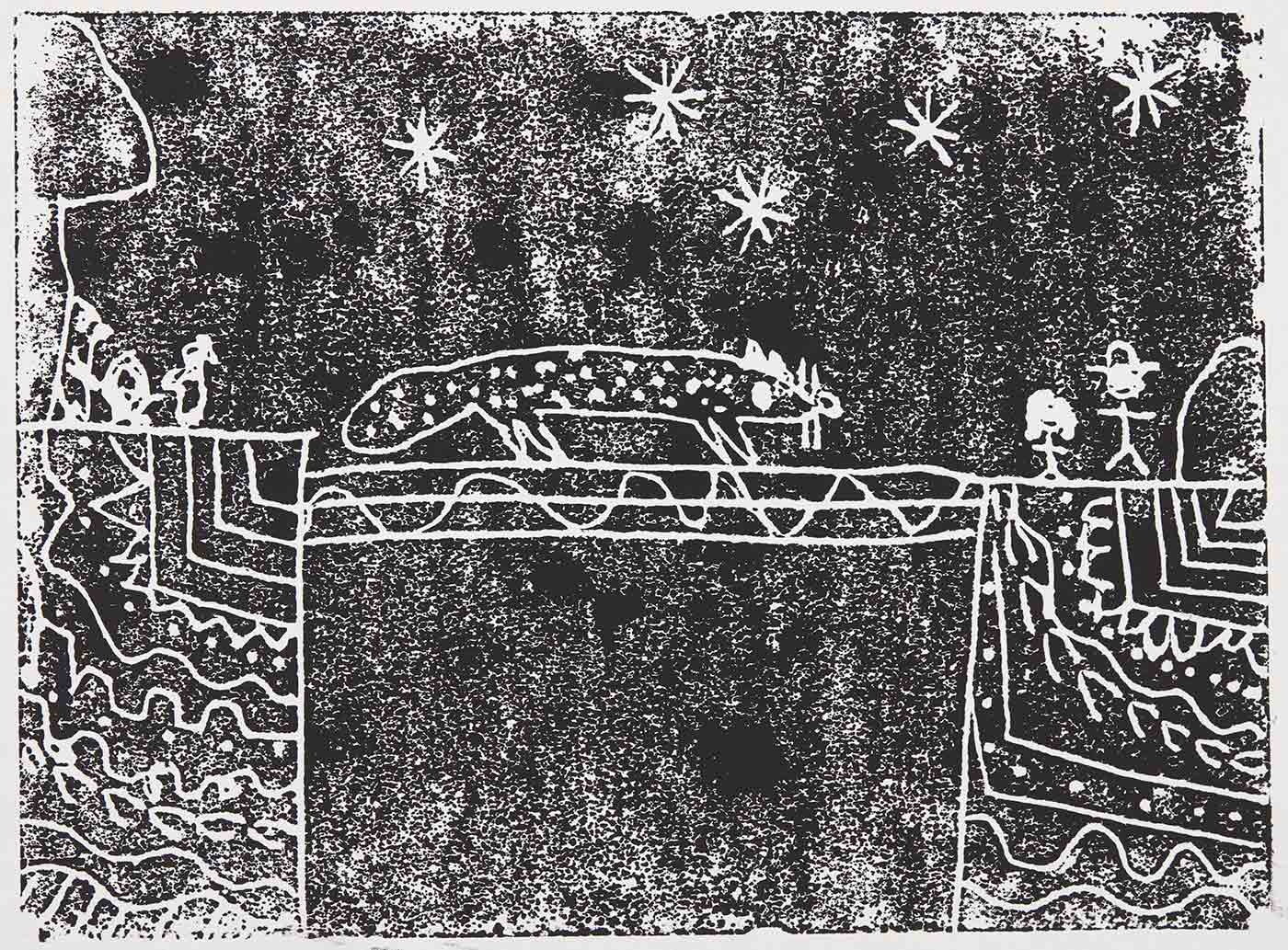

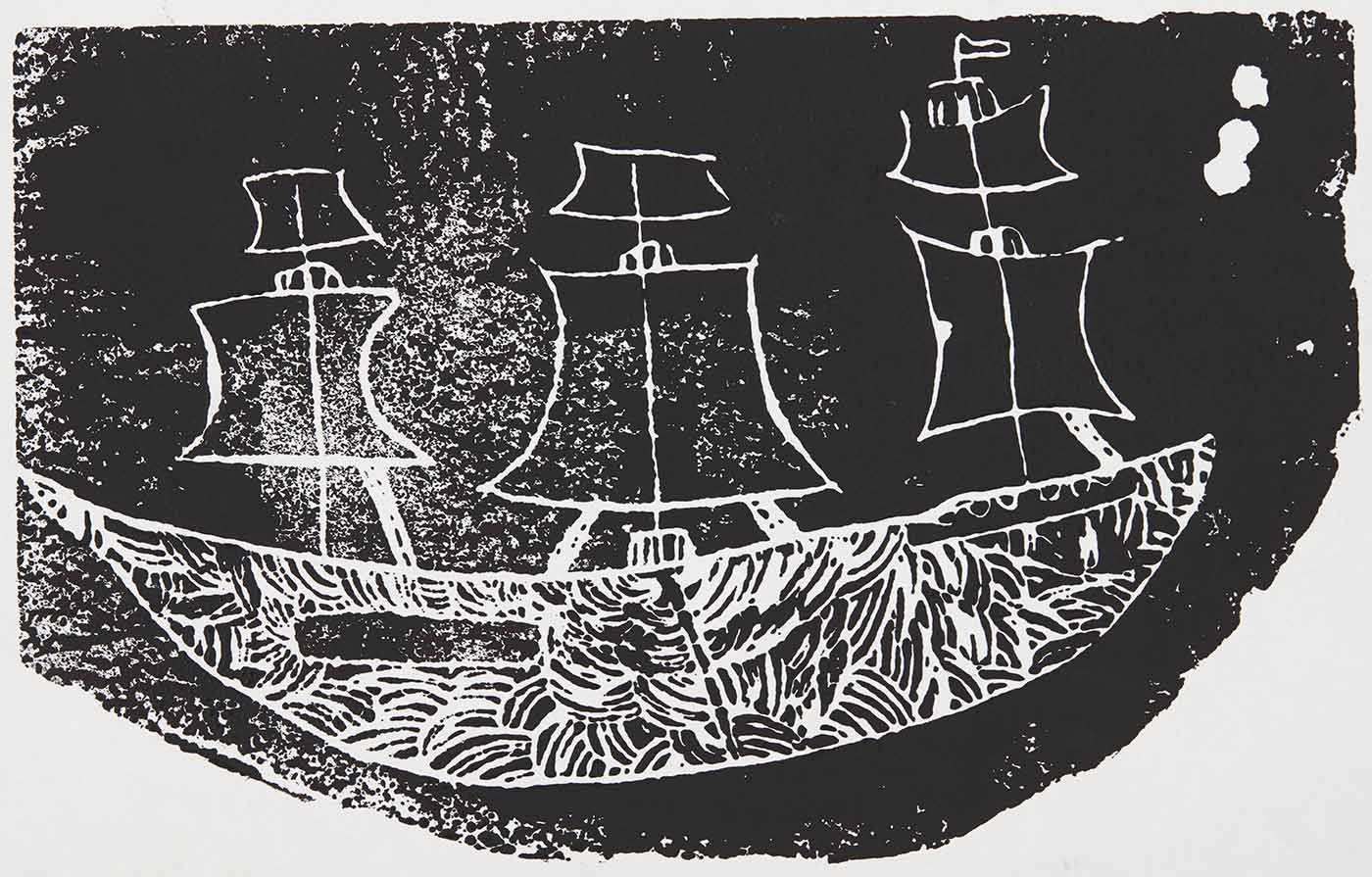

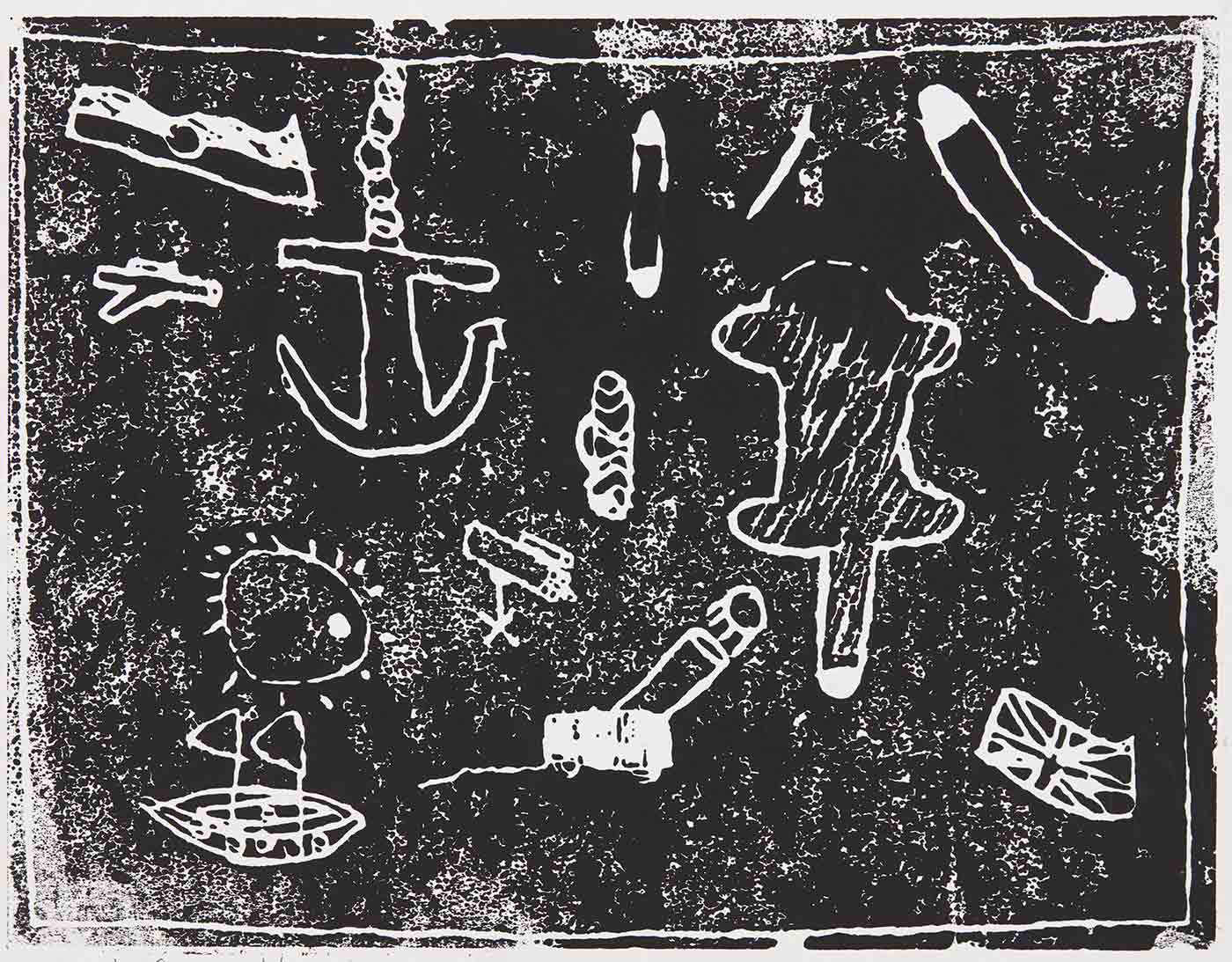

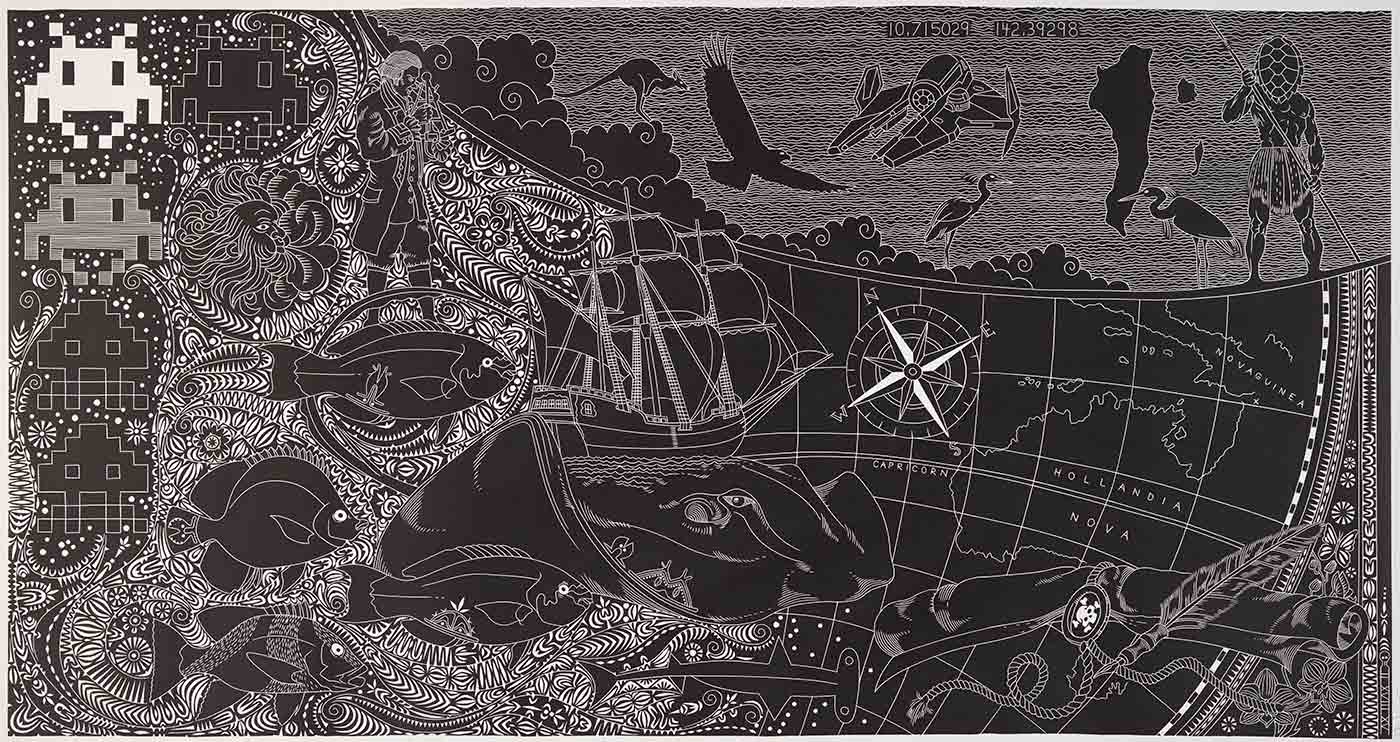

In this print, Torres Strait artist Brian Robinson creates a rich vista inspired by Cook's landing at Possession Island.

Drawing on traditional motifs of the Kaurareg people and traditional symbols of discovery, Robinson challenges the viewer. Was Cook an explorer or a space invader? Were his efforts to chart the coast an act of cartography or of piracy? Is the Endeavour a ship or an alien spacecraft?

Spot the difference

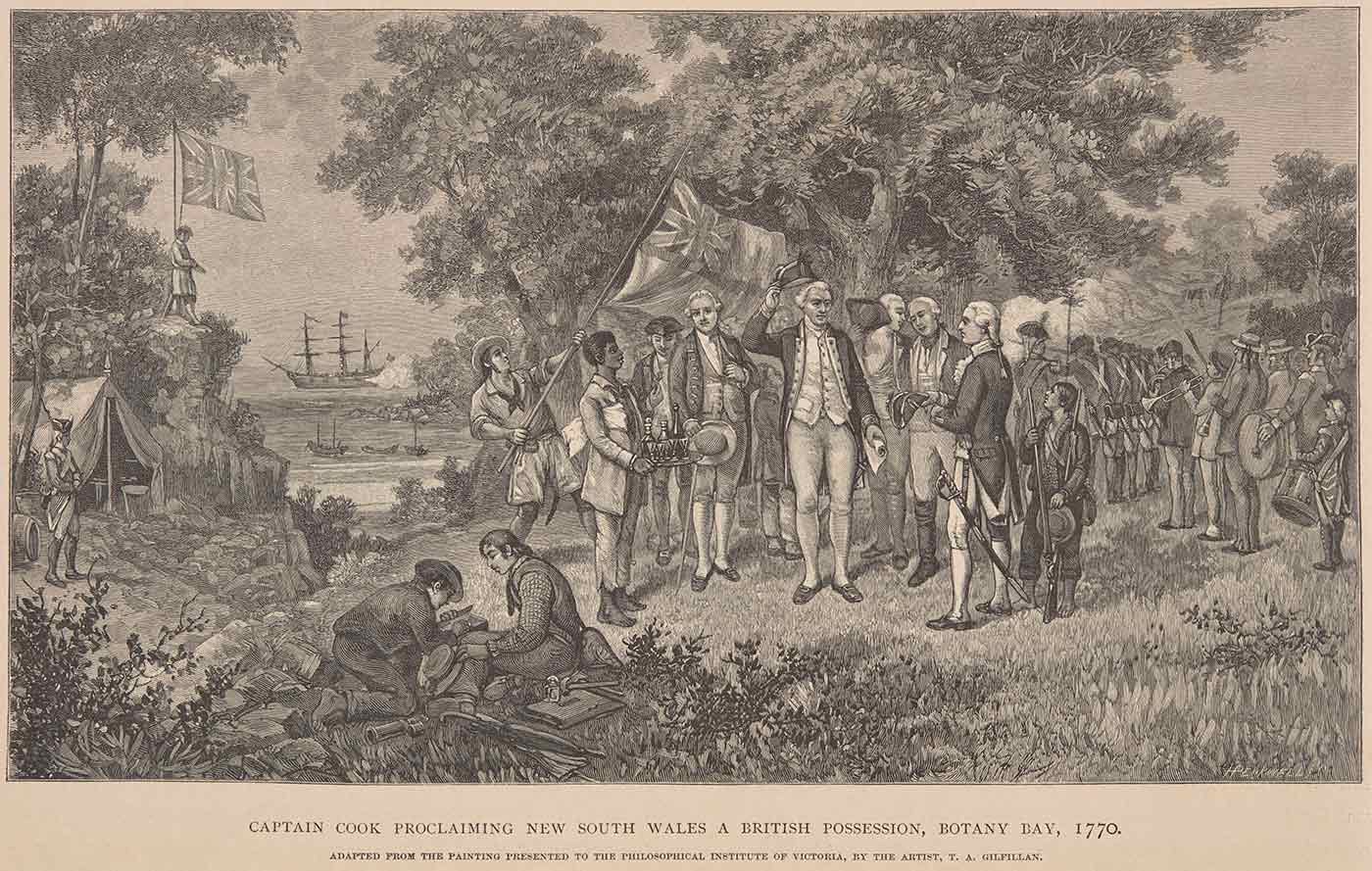

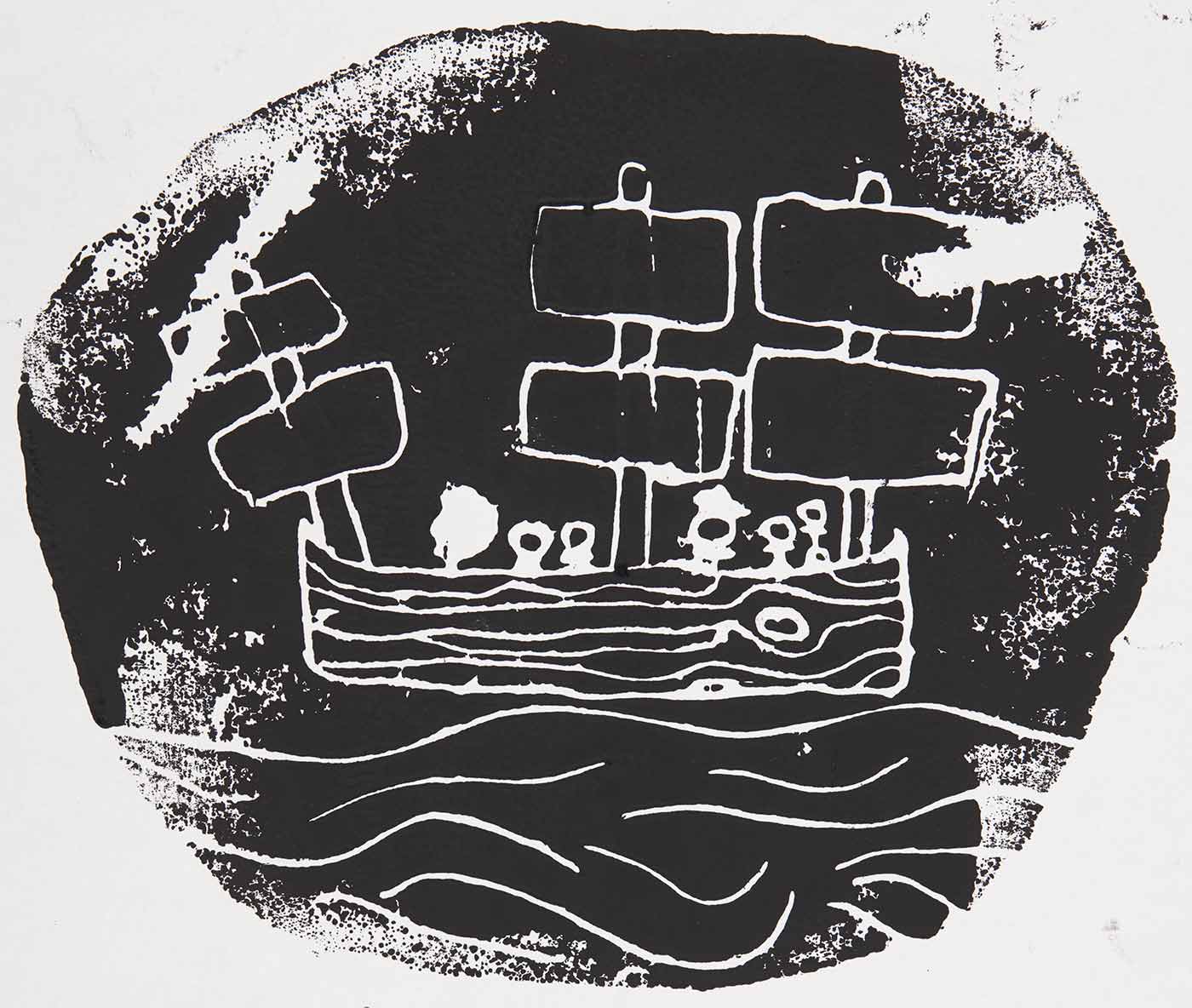

These two prints are based on JA Gilfillan’s grand painting that imagined the moment in 1770 when Cook claimed the land.

Both versions depict a scene of military pomp, but there are significant differences. In Samuel Calvert’s earlier colour version, two Indigenous men have dropped their weapons and cower in terror, while in the background people are fleeing.

In the later black and white version, Australia’s Indigenous people have been removed. The only black person remaining is a servant, holding a tray of drinks. The island has become, in effect, terra nullius.

Inverted invasion

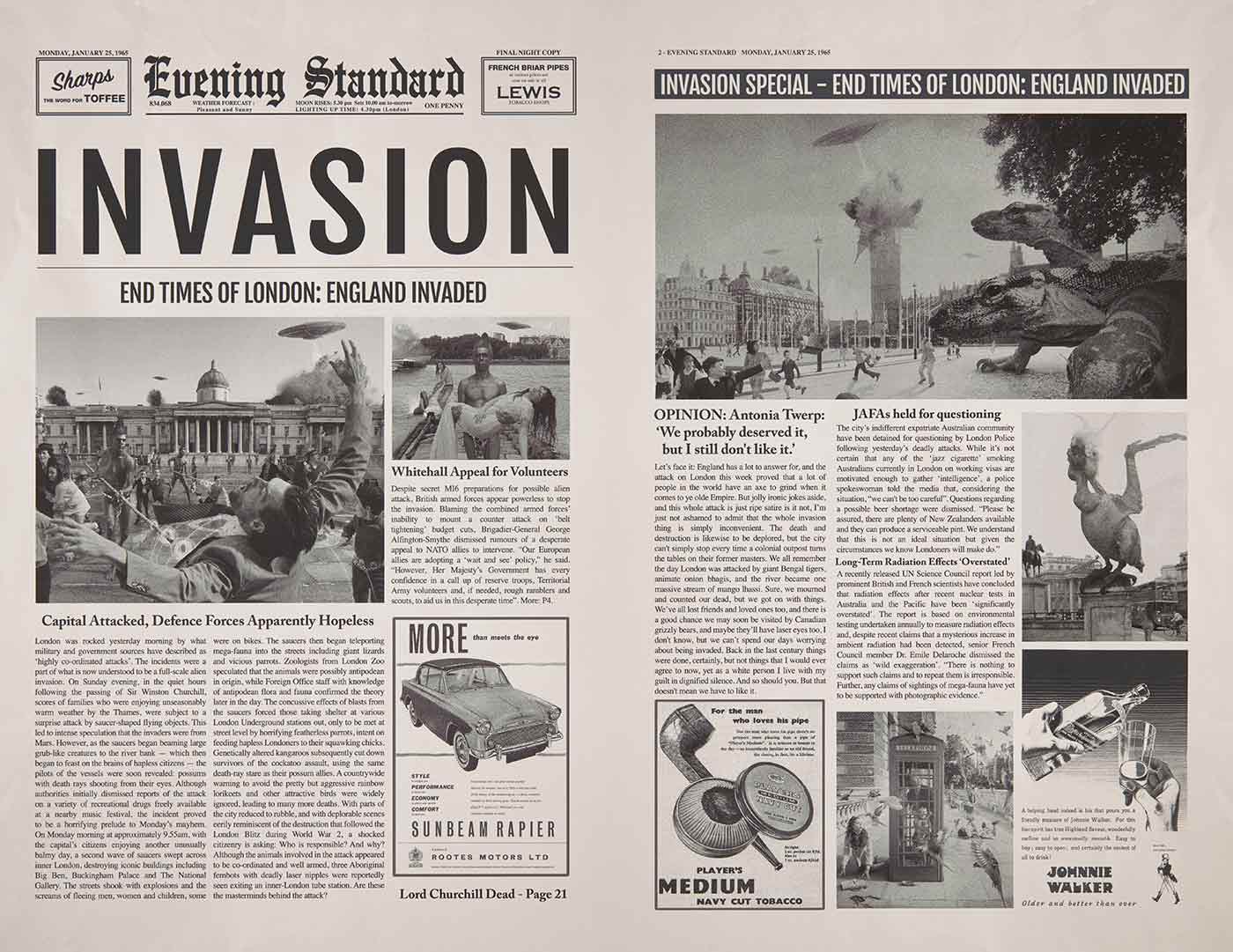

Michael Cook, Bidjara photographer:

These people had pale skin, different hair, elaborate clothing and arrived firing muskets. I wondered, what could be an equivalent to that level of shock, something way outside existing experience, and even imagination.

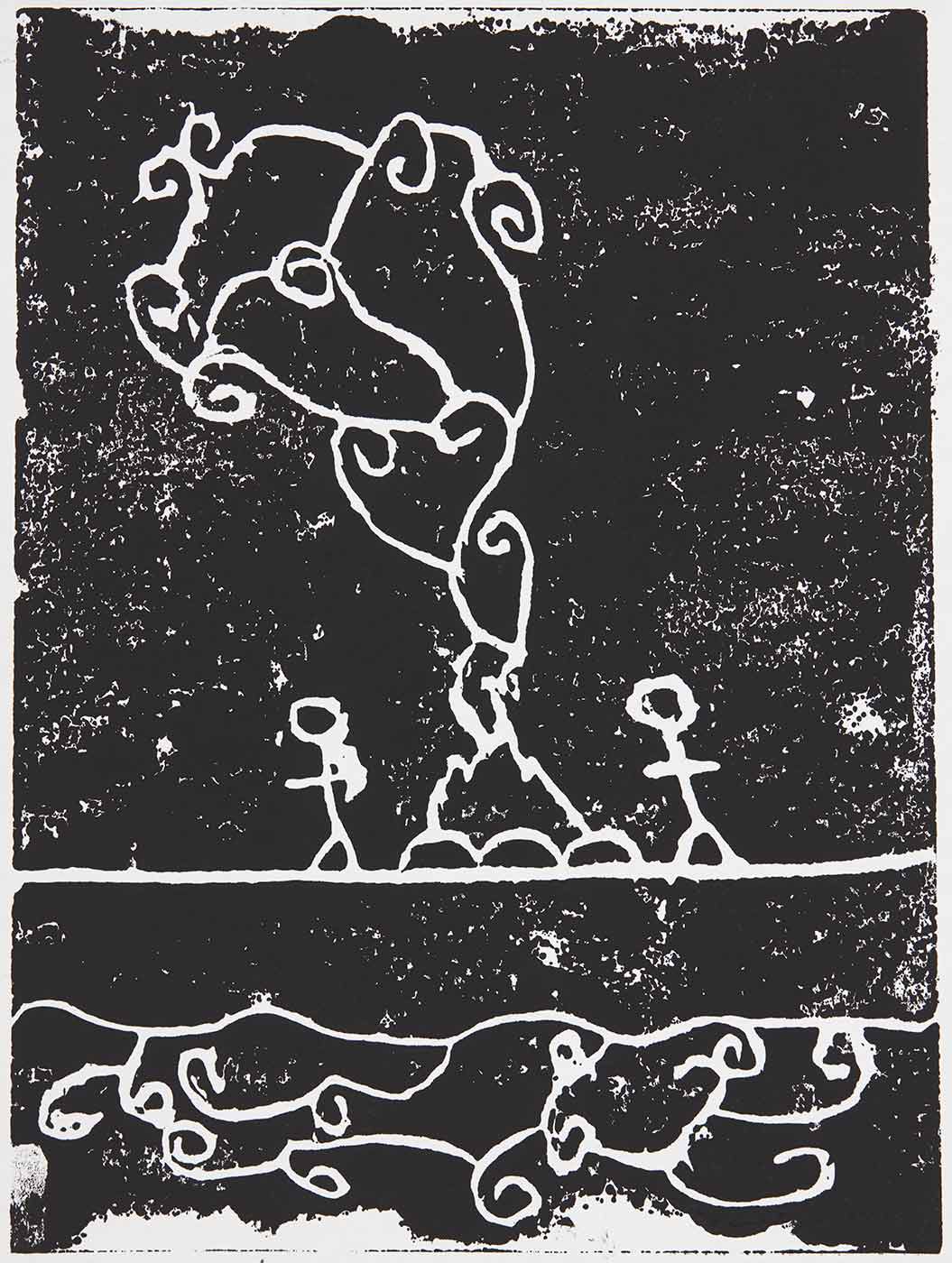

It took Michael Cook eight months to create Invasion, an ambitious photographic series showing an alien incursion into the heart of London.

The artworks turn the tables on the events of 1770. They imagine 1960s London invaded by Australian Indigenous people and animals in alien spacecraft. The whimsical, B-grade horror-movie aesthetic belies the underlying message of a catastrophic attack with earth-shattering consequences for a peaceful, civilised place and people going about their daily lives.

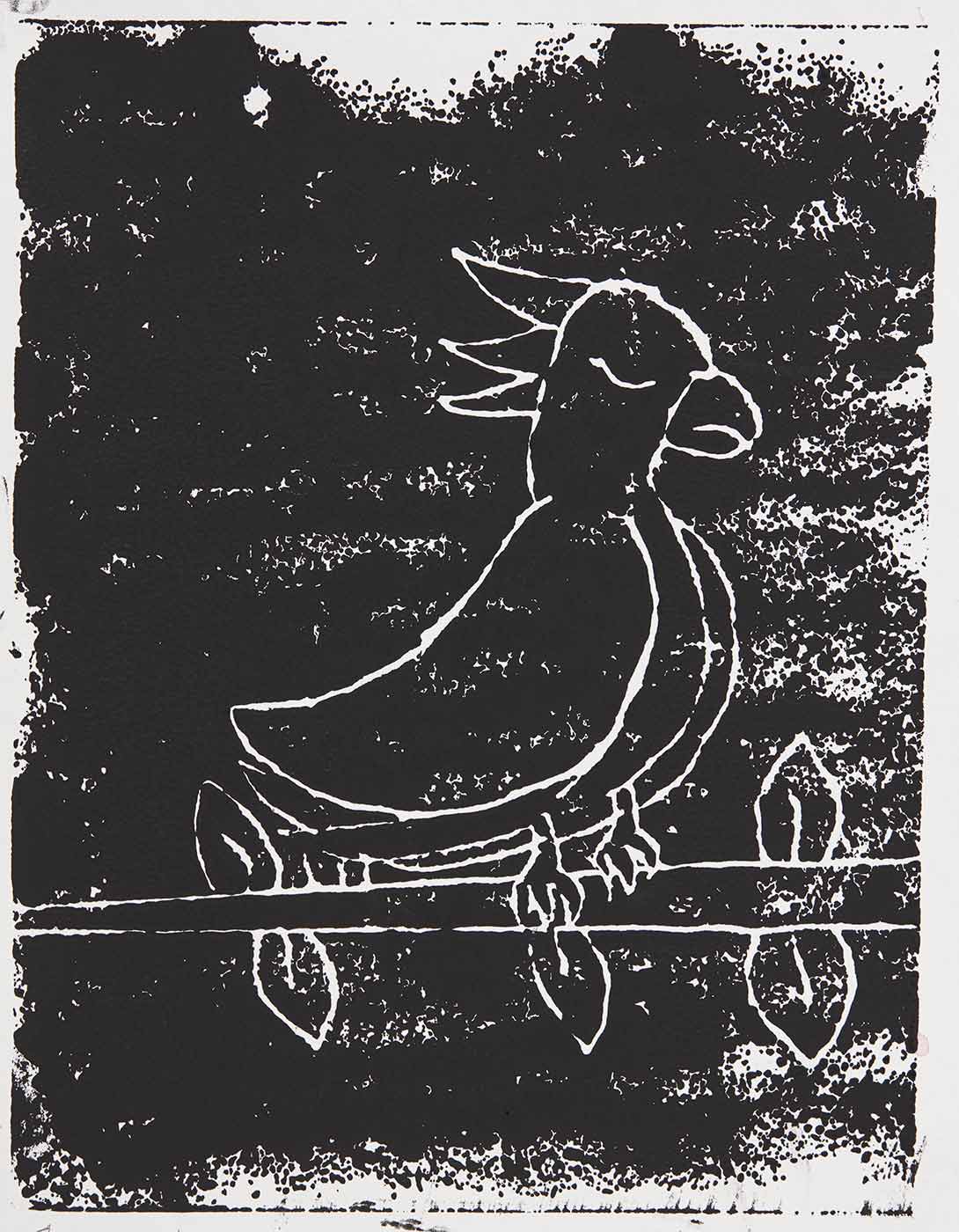

On the beach

It is on the beach where stories about Cook come alive. These organic works by artists from the Bana Yirriji Art Centre, south of Cooktown, offer new perspectives.

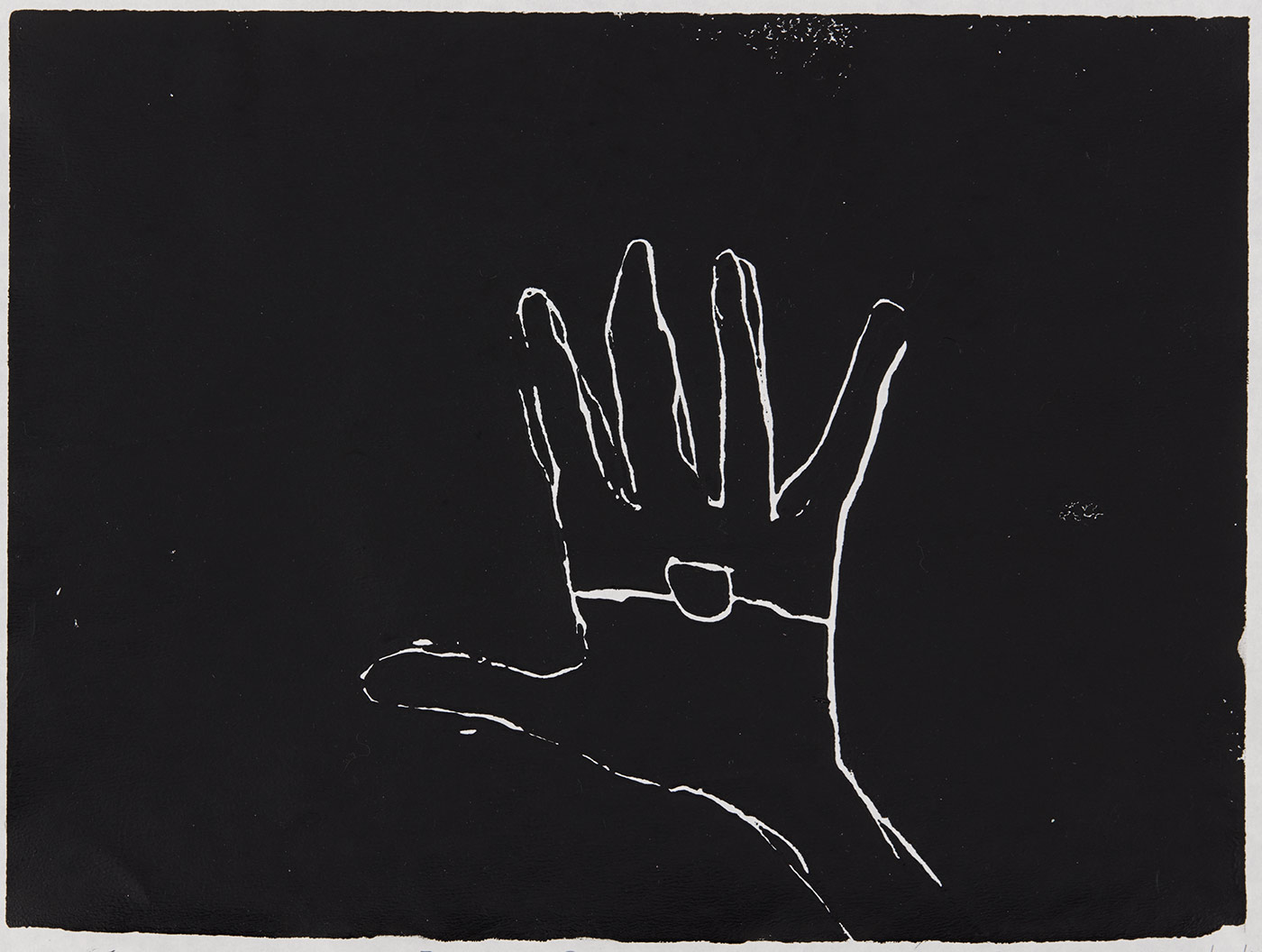

Explore the worksCook’s calming hand

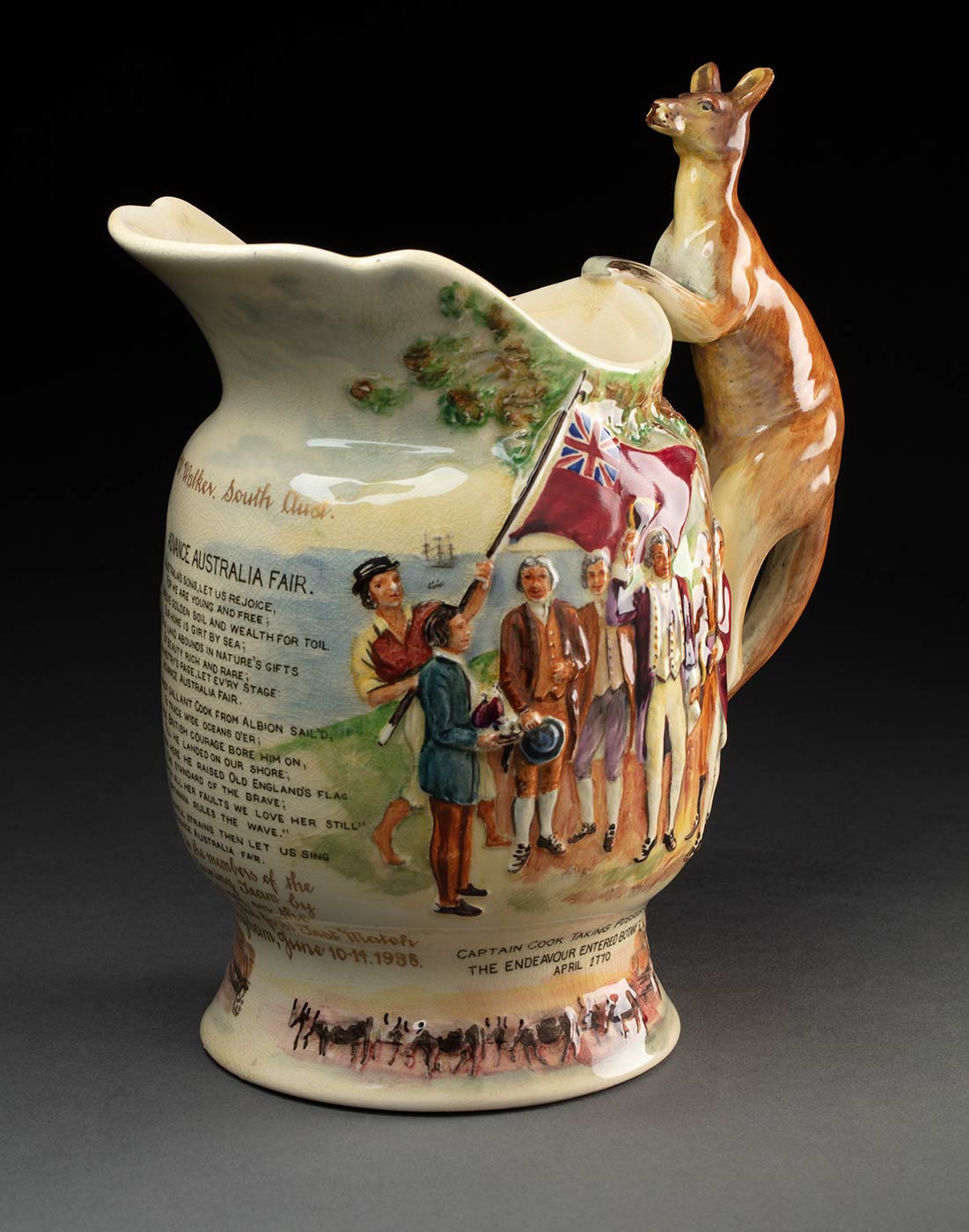

The dramatic moment when Cook and his crew sailed into Botany Bay and stepped onto the Australian mainland has been endlessly imagined and reproduced on memorabilia and souvenirs. These objects all show parts of that drama.

The shield presents an Indigenous perspective. Cook and his crew remain in their longboats, prevented from landing by men brandishing spears.

The cup and the card show Cook taking control in a potentially volatile situation. He raises his hand to calm a marine firing on the Indigenous men. The jug displays the moment of the raising of the British flag over Dharawal land.

What did Cook really look like?

The figure of Cook we find so familiar today has evolved over time. The wig, the cocked hat, the uniform, the map — whether he is depicted as a man or a small furry animal, Cook is instantly recognisable. Maps and map-making, symbolising knowledge, ownership, access and control, feature in both these collectable objects.

Dark portraits

A hundred years and a gulf of experience separates these two portraits. Across the north of Australia, from the Gulf to the Kimberley, Indigenous stories and performances present the arrival of Cook as the starting point of frontier violence and dispossession.

Senior Garrwa man Dinny Nyliba (McDinny) often painted works about violent events he lived through on cattle stations near Borroloola in the Northern Territory. His dark portrait of Cook emerges from the Indigenous stories and performances that extend well beyond the east coast of Australia. By contrast, the portrait by Sydney postman and self-taught sculptor John Baird sits firmly in the traditional European portrayal of the ‘great man’.

Steaking a claim

At Point Lookout on North Stradbroke Island, a nondescript brick monument with a bronze plaque marks Cook’s naming of this feature.

On 26 January 2019, David Yowda Stevens, a traditional owner from the island, made a political protest, removing the plaque and using it as a barbecue plate to cook a steak. After sharing photographs on Facebook, he was charged with wilful damage and theft.

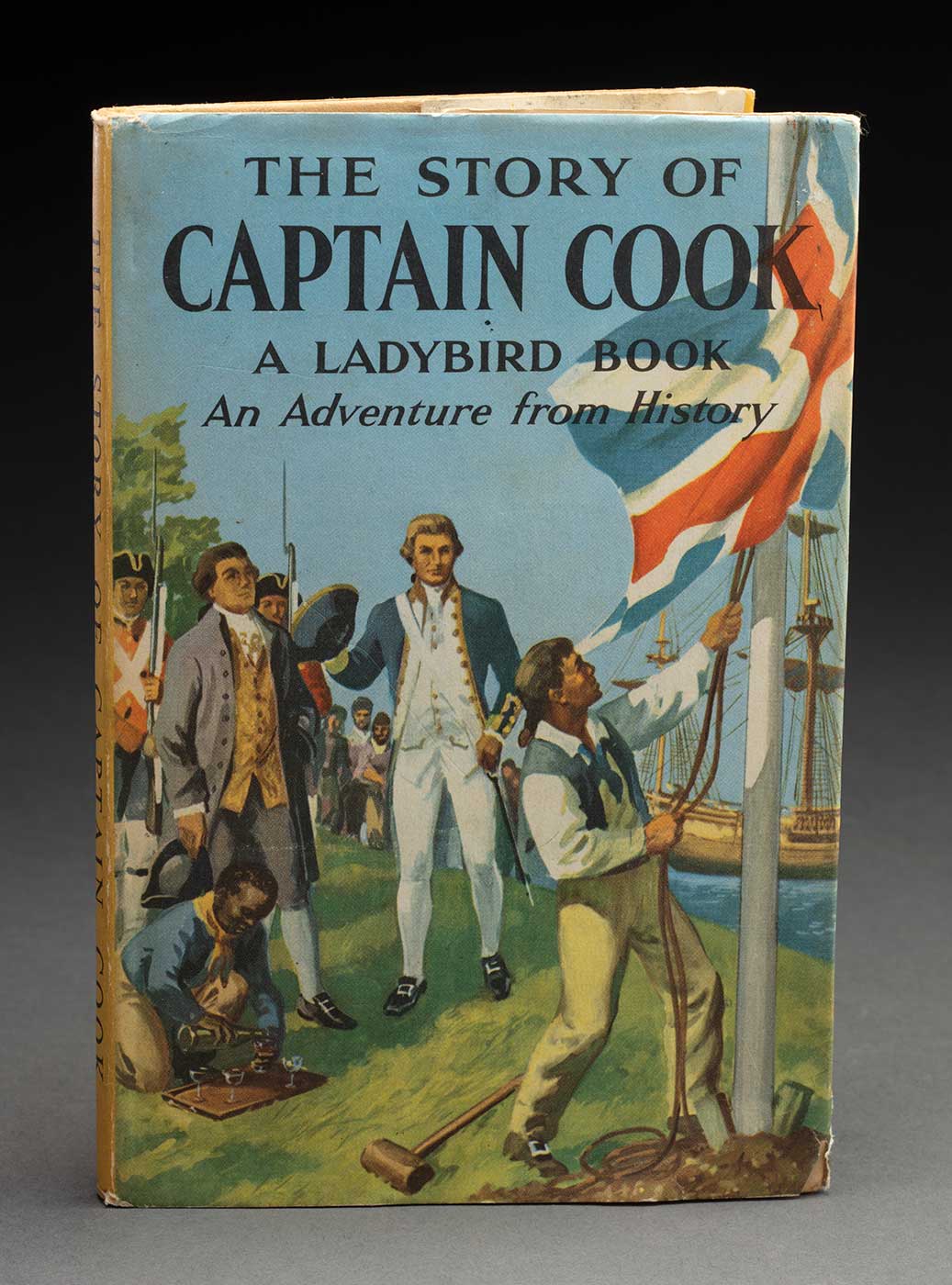

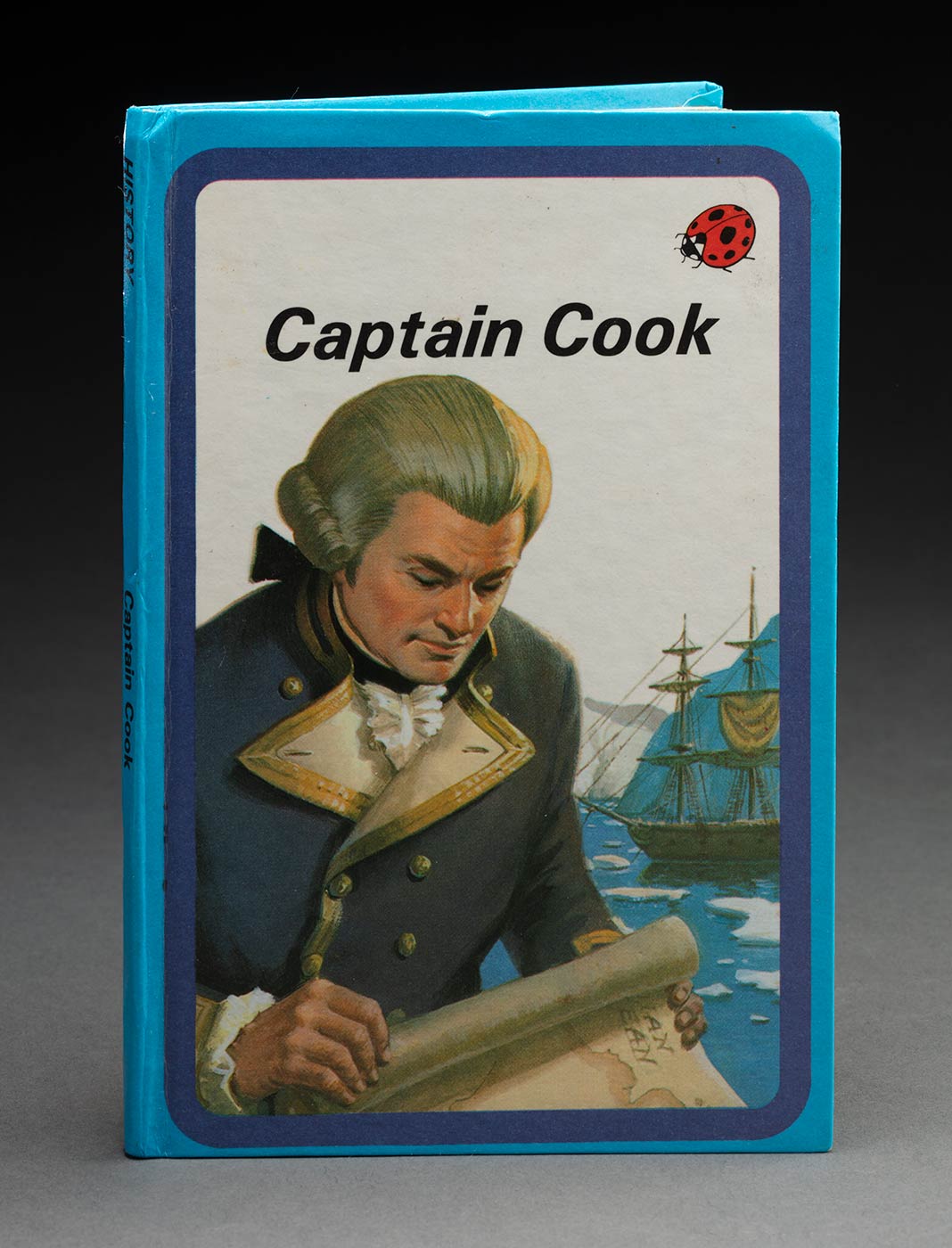

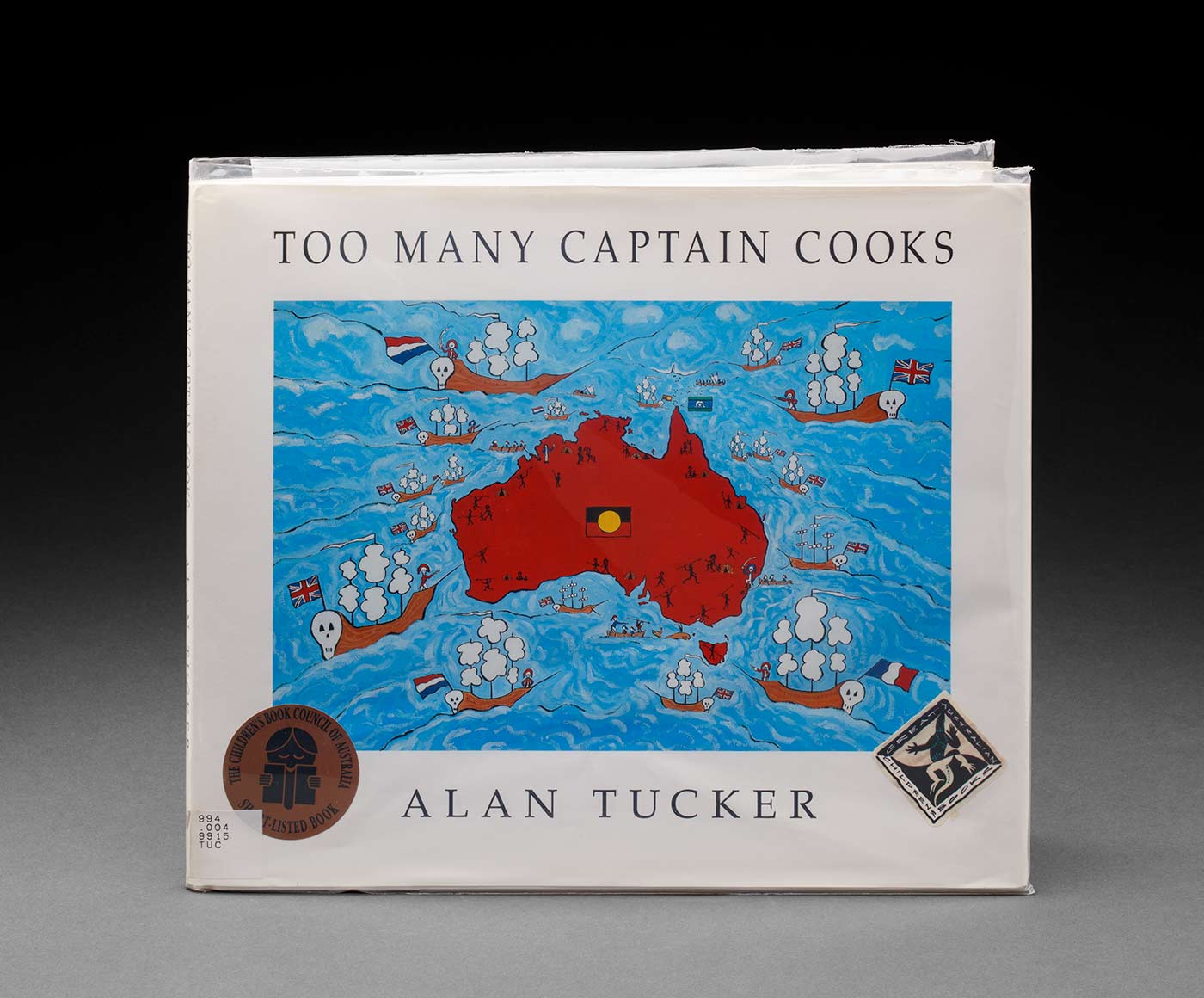

Children's books

The stories we choose to tell our children reflect how we see ourselves and our history. Up until about 20 years ago, children’s books about Cook were simplistic narratives of heroic exploration and empire.

More recent books, such as Alan Tucker’s Too Many Captain Cooks, have started exploring Indigenous perspectives on colonisation, European settlement and dispossession.

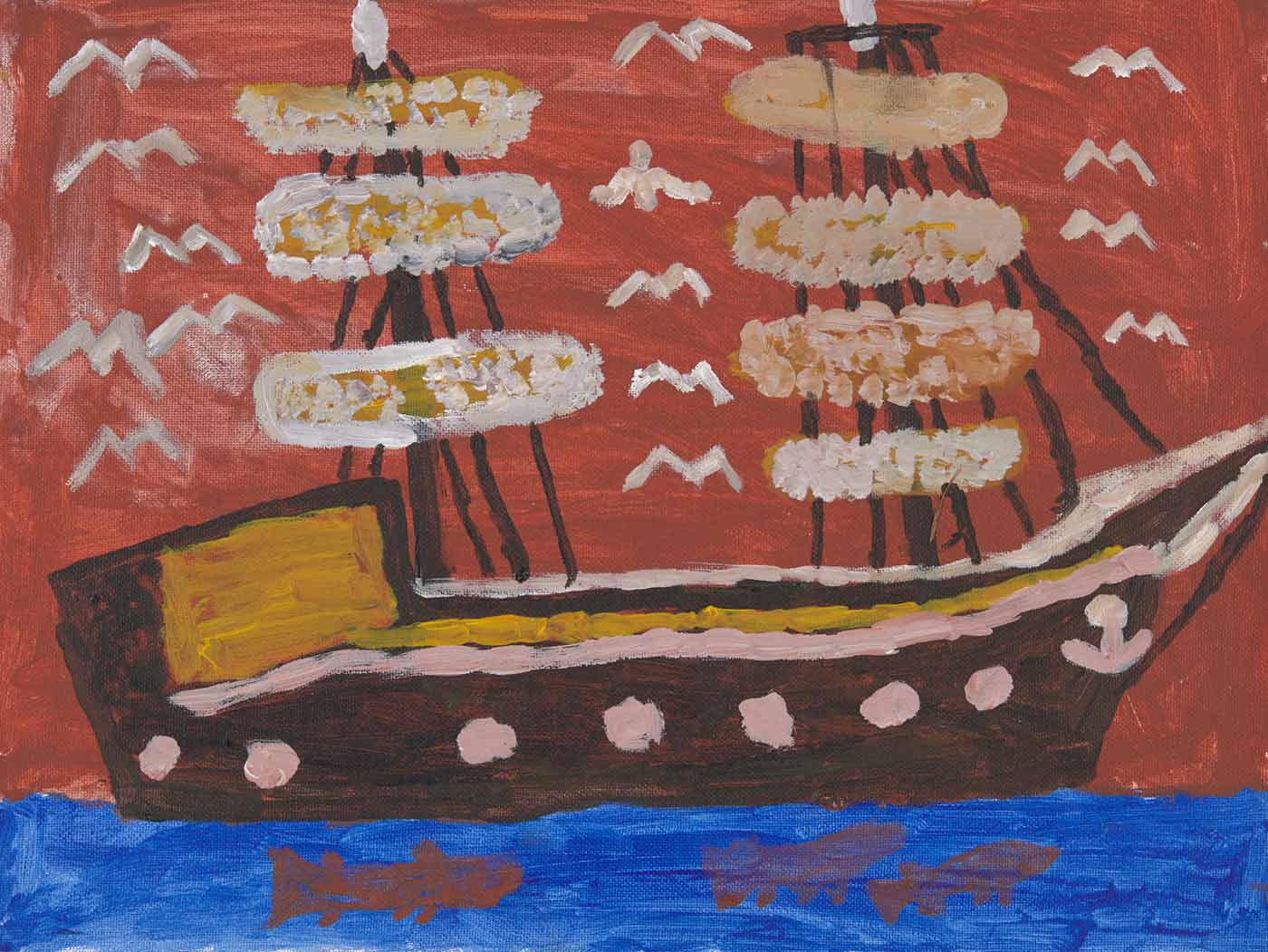

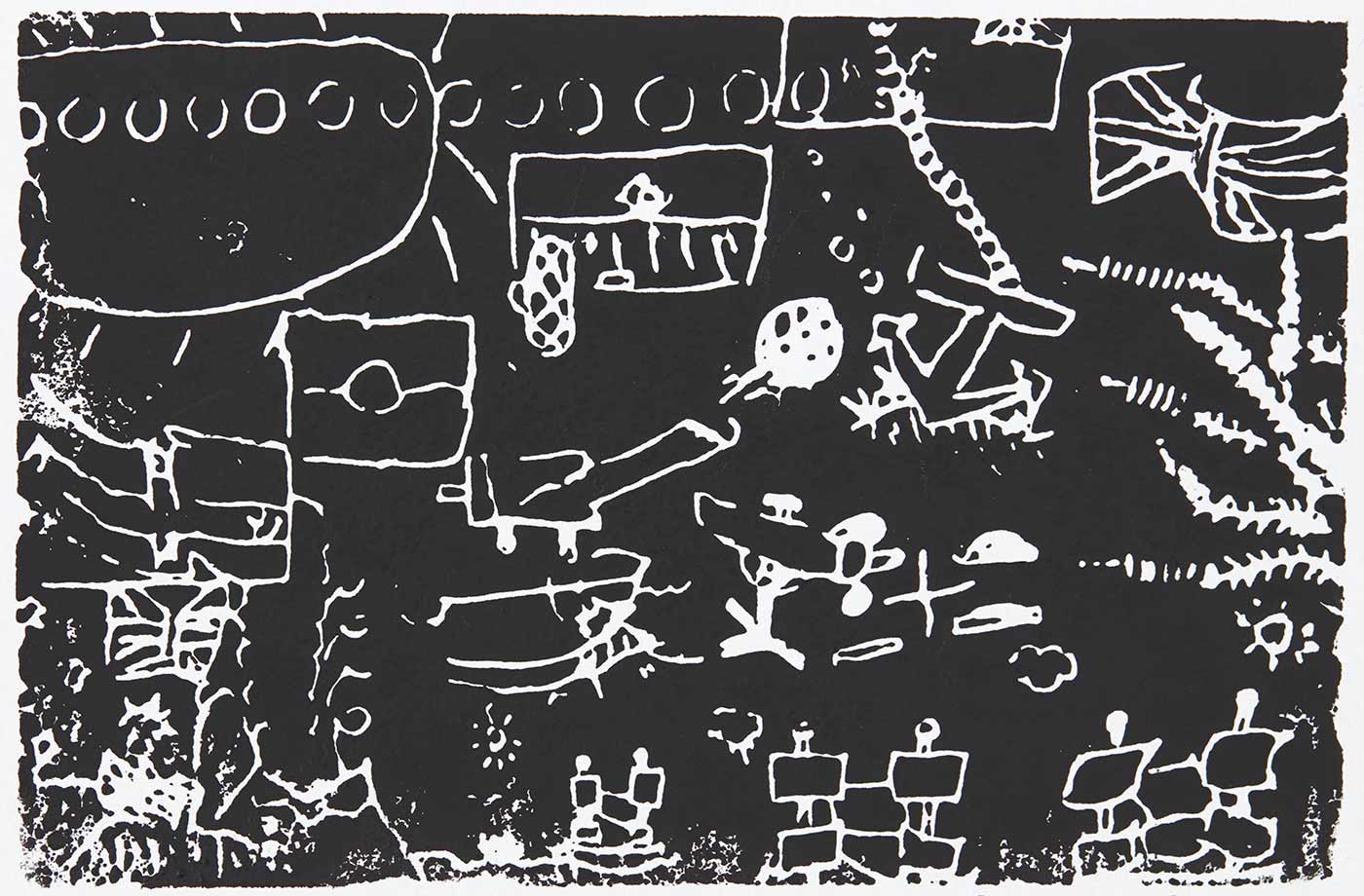

What do the children think?

In the lead-up to 2020, the Museum worked with children in schools in Canberra, La Perouse and Cooktown to create artworks inspired by the Cook and Endeavour stories.

See more children's artworks from students at Cooktown State School

BabaKiueria

The 1986 film BabaKiueria is a mockumentary in which roles are reversed: Indigenous people are the colonisers and white Europeans are the colonised. It was awarded the United Nations Media Peace Prize in 1987.

More than 30 years after it was created, the film still offers a different way of thinking about the politics of first contact. Directed by Don Featherstone, it starred Michelle Torres, Bob Maza and Kevin Smith.

Watch an excerpt from BabaKiueria on the National Film and Sound Archives website.

1970: Celebration and protest

Many Australians marked the Endeavour bicentenary with enthusiastic celebrations. Re-enactments were staged, statues unveiled and flags raised.

A pivotal moment occurred on 29 April 1970, when the Royal Yacht Britannia sailed into Botany Bay carrying Queen Elizabeth, the Duke of Edinburgh and Princess Anne. Proceedings included a re-enactment of Cook’s landing, followed by speeches, a tree-planting ceremony, fireworks and a formal reception.

Across the bay at La Perouse the event was marked differently. Declaring a day of mourning, Indigenous activists gathered to throw wreaths into the water.

The Australian, 30 April 1970:

White Australians lit the sky over Sydney Harbour with fireworks — black Australians stared back down a dark corridor into genocide.

See photos from 1970 and 2018 commemorations at Waalumbaal Birri (Endeavour River)

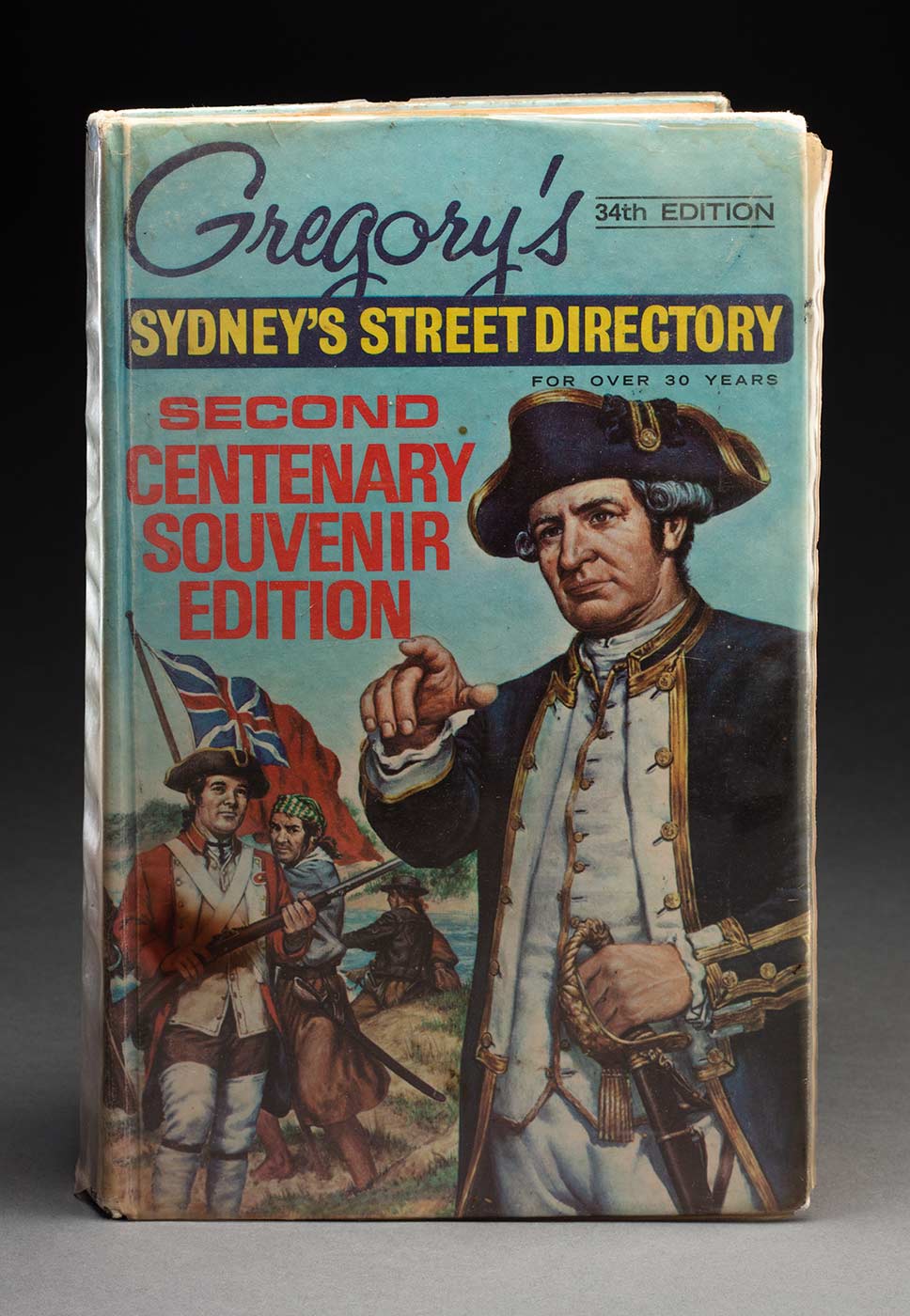

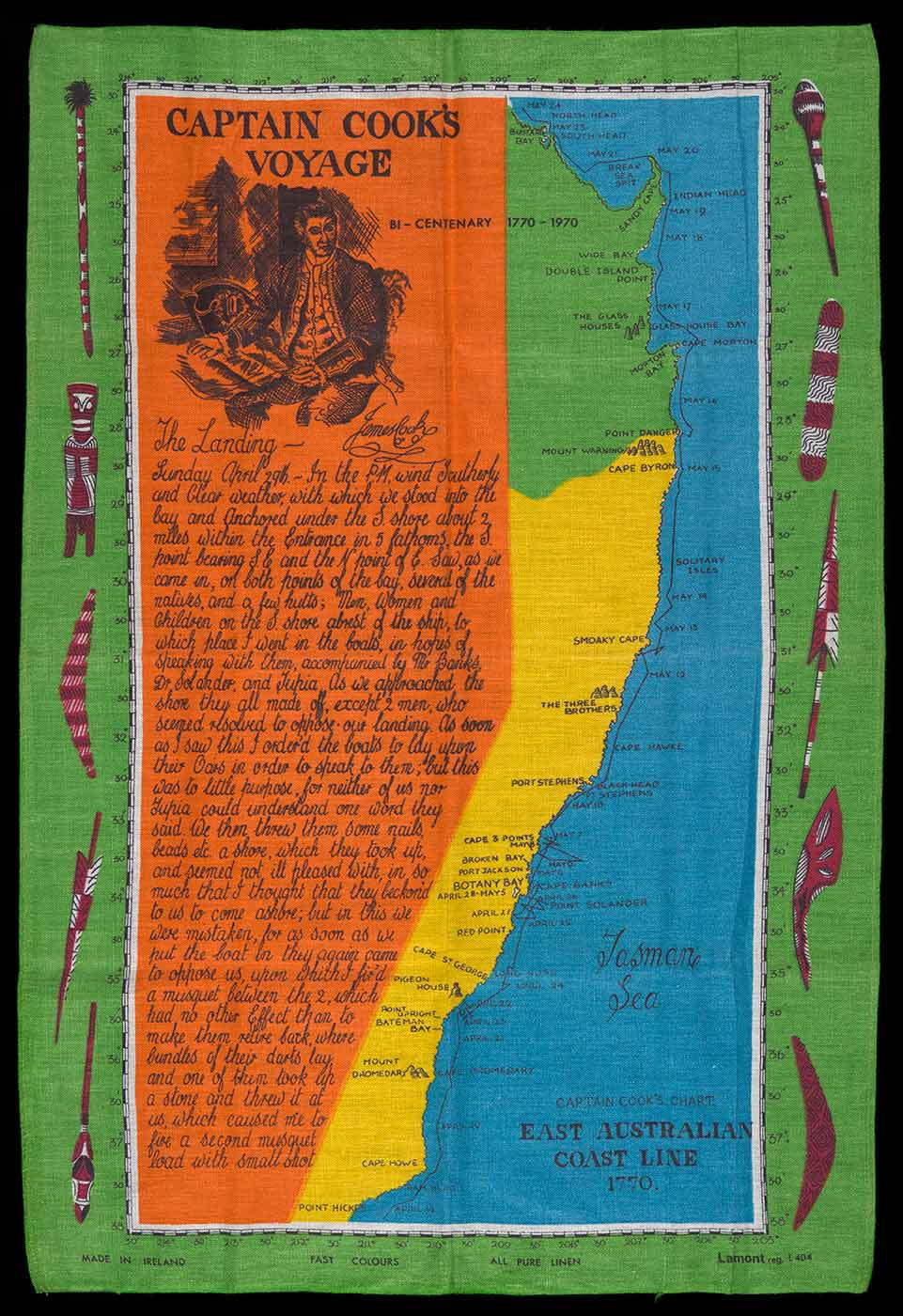

Endeavour bicentenary memorabilia

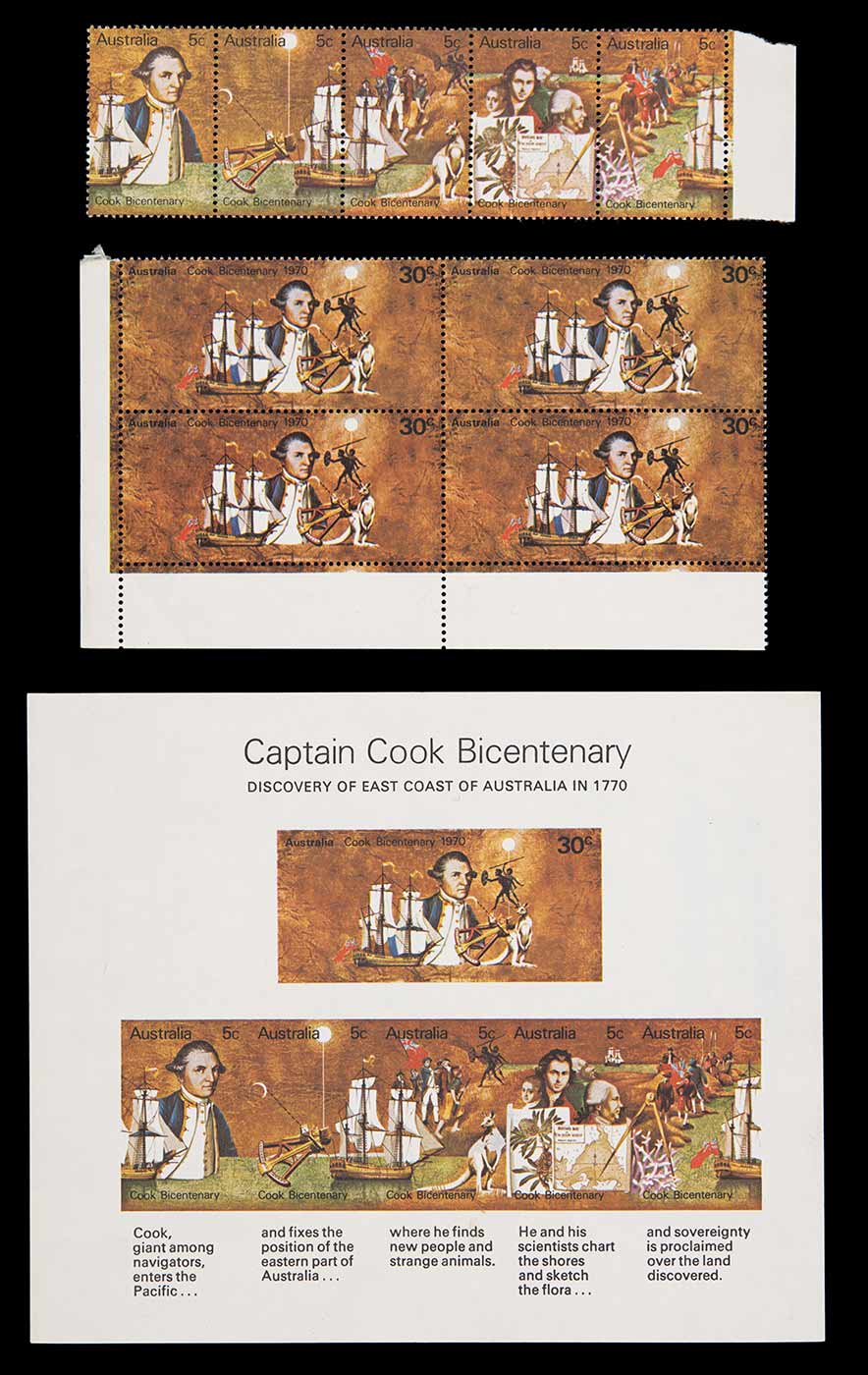

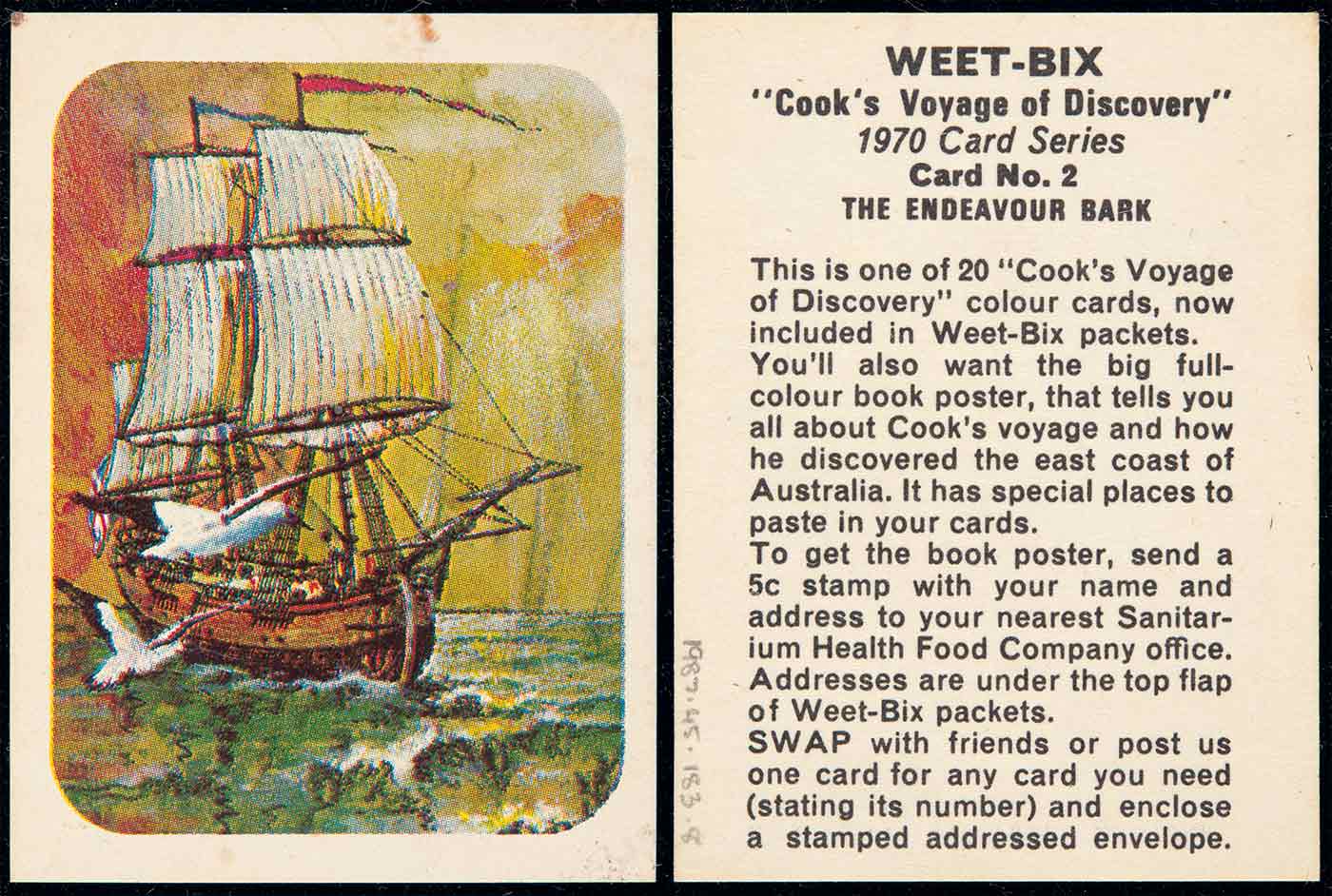

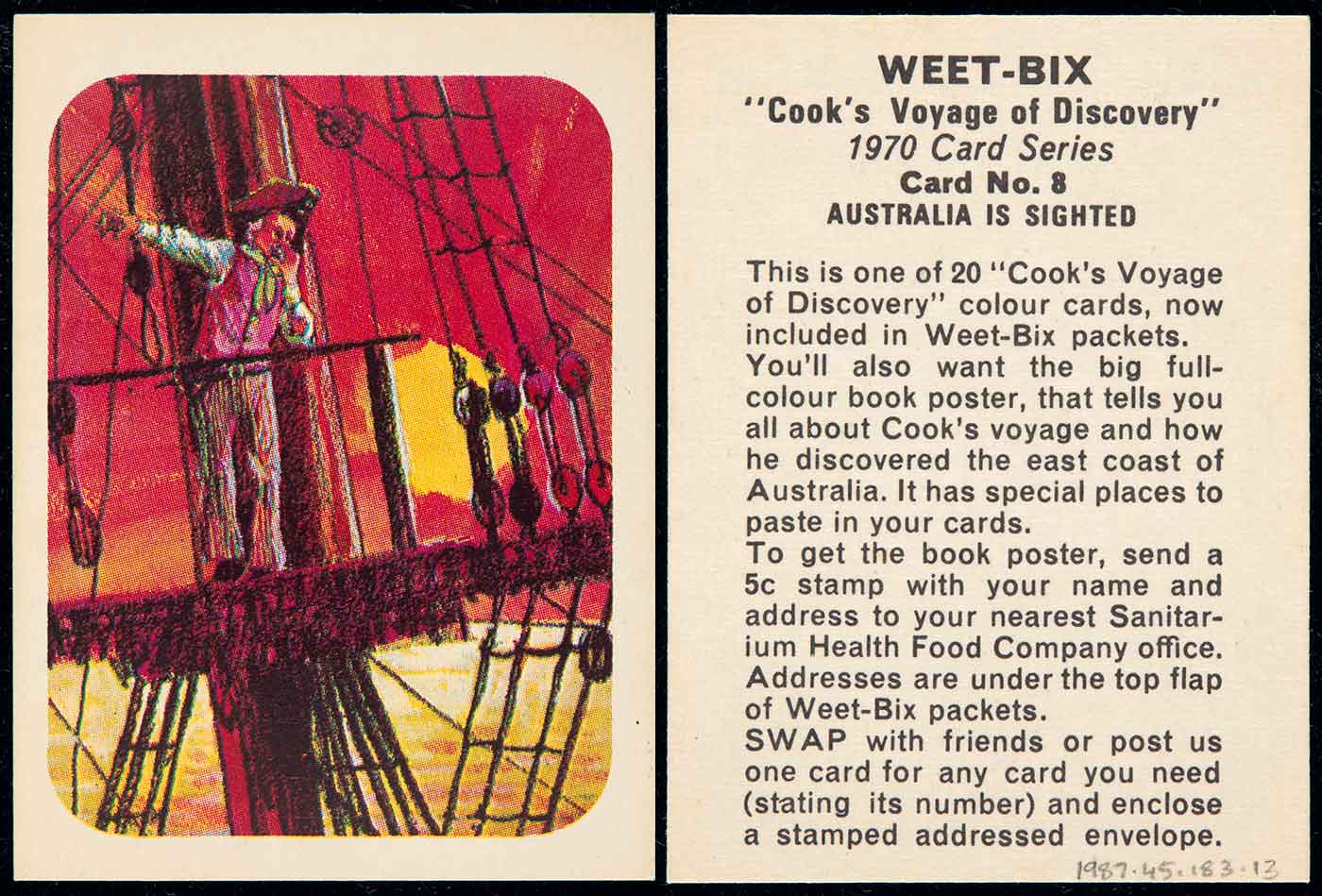

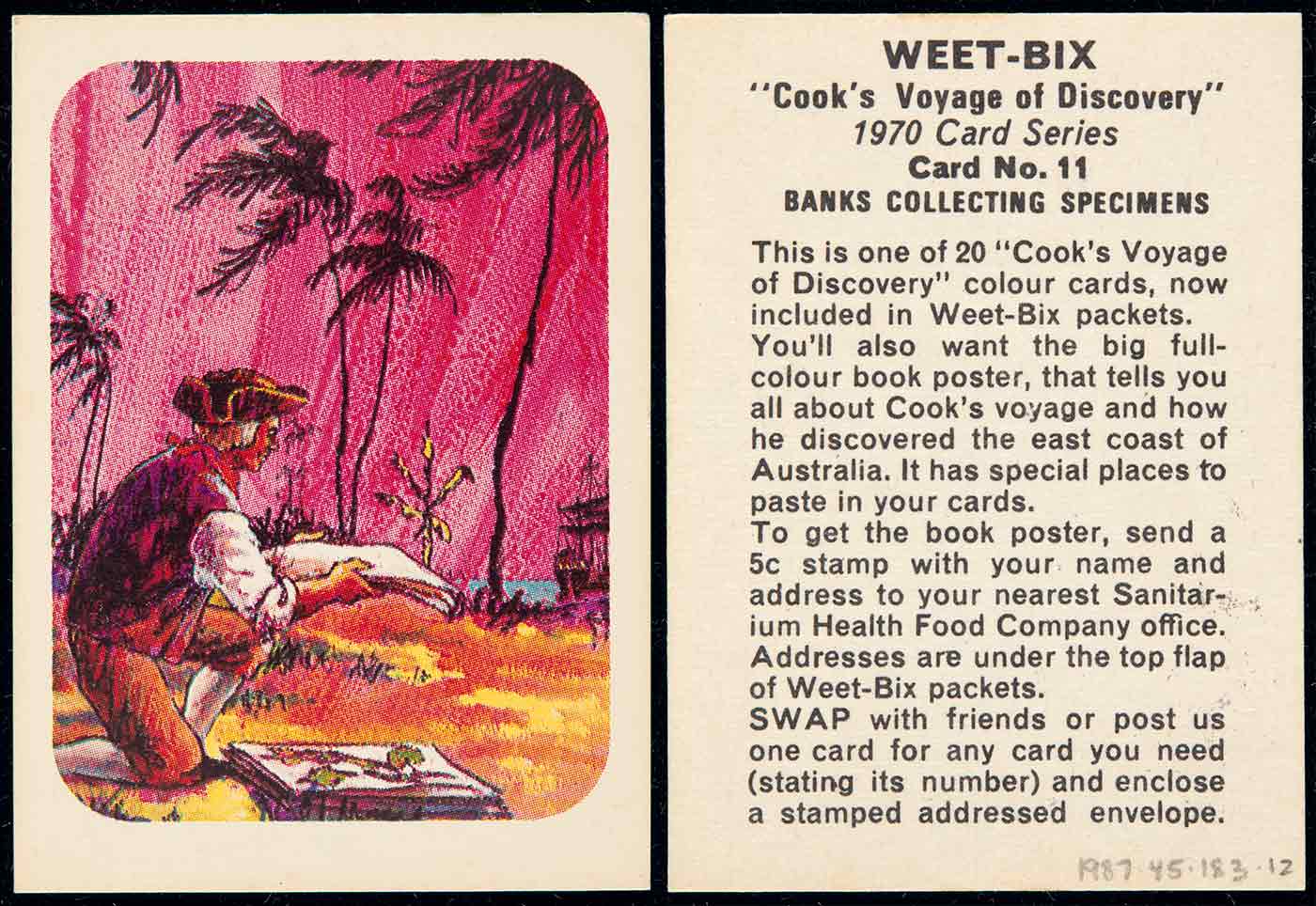

In 1970 Australians were faced with Cook from the moment they searched their packet of breakfast cereal in the morning for the latest swap card, or licked a stamp, or reached into their pockets for one of those funny-shaped new 50-cent pieces.

Those considered the best minds and artists at the time were brought together to produce the official commemorative stamps and coins. The team that designed the lavish Cook bicentenary stamps included novelist Thomas Keneally, artist Robert Ingpen and graphic designer Arthur Leydin.

Australia’s first decimal commemorative coin was the 50-cent piece. It was designed by London-based Australian artist Stuart Devlin and featured the image and signature of Cook and a map of Australia.

Bicentenary stamps and miniature stamp sheet, 1970

Bicentenary 50-cent piece, 1970

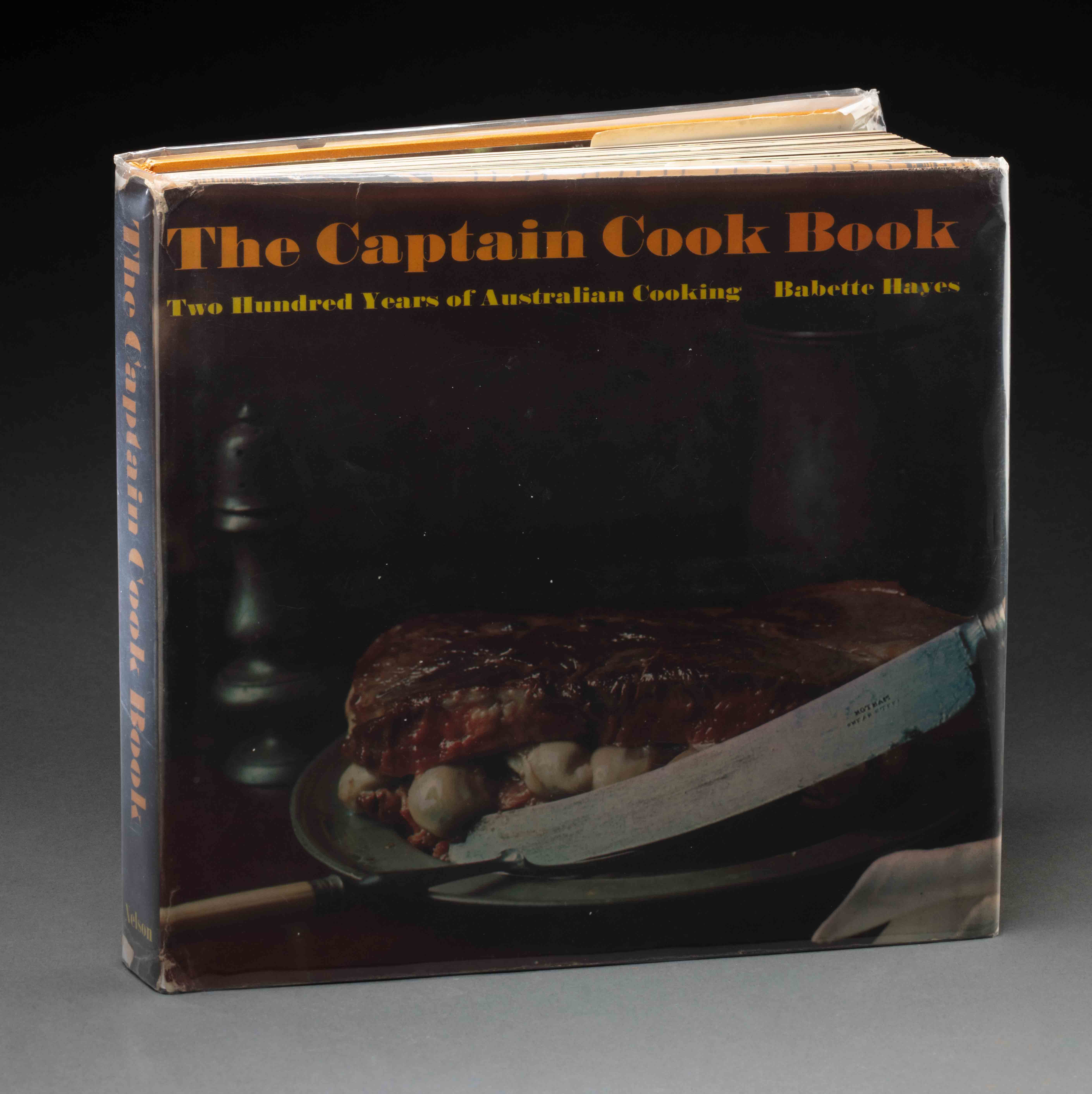

The Captain Cook Book: 200 Years of Australian Cooking by Babette Hayes

‘The Endeavour Bark’ swap card

‘Australia is sighted’ swap card, 1970

‘Banks collecting specimens’ swap card

'New places are named’ swap card

'Saving the Endeavour’ swap card

Joining the dots

James Cook, 23 August 1770:

The Latitude and Longitude of all or most of the principal head lands, Bays &Ca may be relied on, for we seldom faild of geting an Observation every day to correct our Latitude.

As the ship journeyed up the coast, Cook mapped all he saw, filling in the gap between the known points of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) and New Guinea.

Cook caught only a tantalising glimpse of the country beyond and his map is largely restricted to the coastline and immediate surrounds.

Although the map Cook made is accurate, the impression it gives of a singular, homogenous land obscures the fact that the Australian continent belonged to hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations.

The power of naming

Across the length and breadth of the country, the words ‘Cook’, ‘Banks’ and ‘Endeavour’ are commonplace. They are all around us, in the fabric of our natural and built environment.

These names remember the events of 1770, but only from one perspective. They ignore the Indigenous knowledge of this continent.

In recognition of these older connections to country, a growing number of places are being renamed with their earlier Indigenous names.

![Captain Cook taking possession of the Australian continent on behalf of the British crown, AD 1770, under the name of New South Wales [picture] / drawn and engraved by Samuel Calvert from the great historical painting by Gilfillan in the possession of the Royal Society of Victoria. Published Illustrated Sydney news. 1865 Dec. - click to view larger image](https://www.nma.gov.au/__data/assets/image/0004/745798/CDC-10707730.jpg)