10°43’21” South 142°23’56” East

This small island is part of the lands of the Kaurareg, Gudang Yadhaykenu, Ankamuthi and other clan groups, who continue to care for it. Some of their ancestors were on the island on the day James Cook landed and claimed possession.

Traditional Owners explain the social and cultural significance of Possession Island for their clan group and discuss the ways every member of the clan had a role to play in gathering food. Produced by the ABC in partnership with the National Museum of Australia. View transcript

One island, many names

The island Cook named ‘Possession Island’ has older names used by different clan groups. These names include Bedanug, Bedhan Lag, Tuidin and Thunadha. It is part of a network of islands lying between Australia and New Guinea.

Kuarareg/Gudang Yadhaykenu Traditional Owners show important food sources they gathered from Possession Island. Produced by the ABC in partnership with the National Museum of Australia. View transcript

Whose land?

James Cook, 22 August 1770:

We saw on all the Adjacent Lands and Islands a great number of smooks a certain sign that they are Inhabited.

Although he observed evidence of people all around him, Cook claimed possession of Australia’s east coast here.

At that time, British possession was based on legal assumptions that have become known as ‘terra nullius’, or ‘land belonging to no one’. Throughout his journal Cook described the presence of Indigenous people along the Australian coast. Cook's ignorance of their complex cultural and land management practices meant that he saw the land as being unused and therefore open to British territorial claims.

Gudang Yadhaykenu Traditional Owners take us to the Cook monument on Possession Island, where Cook planted the Union Jack. Produced by the ABC in partnership with the National Museum of Australia. View transcript

An agent of empire

Cook’s act of taking possession was at odds with the advice he had received from James Douglas, President of the Royal Society, which had sponsored the voyage. Douglas’s advice was clear:

They [Indigenous peoples] are the natural, and in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several Regions they inhabit.

Cook’s actions, as a Royal Navy officer, were part of a bigger colonial process, in which Britain and other European powers sought to expand their empires through territorial acquisition.

Charles Woosup, Milton Savage and Nicholas Thompson reflect on Cook's Endeavour voyage. This video has no sound. View transcript

Connected islands

People who live in this area are connected across the islands by family and trade.

Traded objects included bows and arrows like those carried by a man Cook observed on Possession Island.

James Cook, 22 August 1770:

We saw a number of People upon this Island … one man who had a bow and a bundle of Arrows, the first we have seen on this coast.

Smoke and mirrors

Long before Cook arrived, people from this region dealt with unexpected visitors. Tribal warfare, raiding parties and even occasional visits from earlier European explorers were not uncommon.

Clan groups had ways of communicating between islands to warn of impending danger. As well as smoke signals, the blowing of a bu (trumpet shell) and the flashing of a pearl shell’s mirrored surface might have brought news of the Endeavour.

Call to arms

On the islands, clan chiefs would sound bu (trumpet shells) to rally their people. It was a call to arms, urging them to prepare for battle.

Bu were also used by people acting as sentries, watching for anyone approaching from land or sea.

Endeavour Voyage 01 Jan 2020

Bu shell

Written in light

James Cook, 22 August 1770:

Two or three of the Men we saw Yesterday [on Possession Island] had on pretty large breast plates which we supposed were made of Pearl Oysters Shells.

At that time, pearl-shell ornaments showed who was a clan group leader or who had gone through initiation. They also have a practical use: because their shiny surfaces can reflect sunlight over long distances, they can be used to convey messages by flashes of light.

Warriors on the hill

When the Endeavour crew anchored off Possession Island, they noticed a group of men watching them.

Joseph Banks, 21 August 1770:

9 were armed with lances as we had been usd to see them, the tenth had a bow and arrows; 2 had also large ornaments of mother of Pearl shell hung round their necks. The 3 Indians plac’d themselves upon the beach opposite to us as if resolvd either to oppose or assist our landing.

People from here talk about these 10 men as being clan leaders and warriors, waiting for the Endeavour to arrive. After the visitors fired a musket, Banks noted that the men ‘all walkd leisurely away’.

The other side of the story

Seriat Young, Kaurareg:

When you hear it from the elderly people, as soon as you mention Cook, they’ll growl and say, ‘Ah, that bloody no good Cook. He never even set foot on the bloody island!’

Cook’s journal is not the only version of what happened on Possession Island. Some elders connected to the island say they don’t believe Cook came ashore at all. They say he wrapped the British flag around a pistol or a cannon ball and threw it or fired it onto the shore.

Cloth on a stick

Colina Wymarra, Gudang:

The story that my dad told me is when Cook sailed through the Torres Strait he put a flag on Possession Island. The Gudang are seafaring people and they often travel to the island and they saw the ‘cloth on a stick’ stuck in the sand on the beach.

In their innocence, my people’s innocence, they grabbed that and used it as a blanket and covering. ‘Flag’ was not a concept they knew of.

Cook provides evidence

Despite some Indigenous people disputing aspects of Cook’s accounts, parts of the journal have been used to support legal battles for land.

Waubin Richard Aken, Kaurareg:

Going back to 2001 when we entered the Federal High Courts and got our [Kaurareg] native title determination, Cook’s journal entries were used to help our argument and demonstrate that our people were seen on the island way back then.

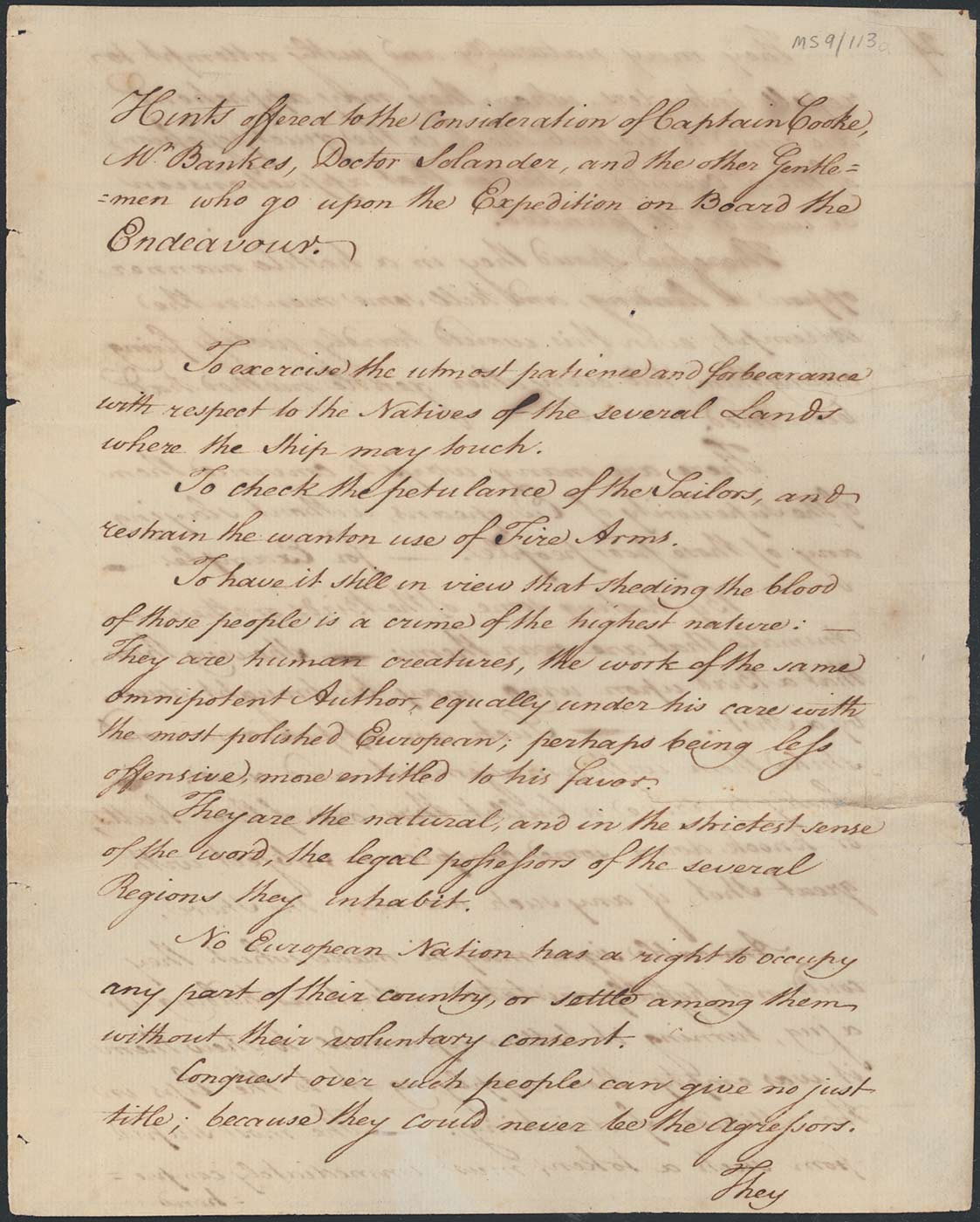

This artwork references Kaurareg people’s continuing fight for their traditional land and waters.

Summing up

At the end of his voyage up Australia’s east coast, Cook reflected on Australia’s Indigenous people. He noted wistfully how they possessed ‘all the necessarys of Life and that they have no Superfluities’.

James Cook on New Holland in Cook's Descriptions of Places and Peoples encountered during the Endeavour Voyage:

From what I have said of the Natives of New-Holland they may appear to some to be the most wretched people upon Earth, but in reality they are far more happier than we Europeans; being wholy unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary conveniencies so much sought after in Europe, they are happy in not knowing the use of them. They live in a Tranquillity which is not disturb'd by the Inequality of Condition: The Earth and sea of their own accord furnishes them with all things necessary for life; they covet not Magnificent Houses, Houshold-stuff &Ca.

they live in a warm and fine Climate and enjoy a very wholsome Air, so that they have very little need of Clothing and this they seem to be fully sencible of, for many to whome we gave Cloth &Ca. to, left it carlessly upon the Sea beach and in the woods as a thing they had no manner of use for. In short they seem'd to set no Value upon any thing we gave them, nor would they ever part with any thing of their own for any one article we could offer them; this, in my opinion argues that they think themselves provided with all the necessarys of Life and that they have no Superfluities — ’

The results of Cook’s voyage were many and far-reaching. His detailed navigational charts and observations brought Australia into the British world.

The voyage also led to the establishment of a penal colony at Sydney Cove 18 years later. This was the beginning of British colonisation of this continent, and it set off a catastrophic chain of events that continues to impact Indigenous Australians today.

Education resources

These resources cater for students in Years 3 to 6 and all activities align with the Australian Curriculum. Years 3 and 4 align with the history content and Years 3 to 6 align with the cross-curriculum priority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures.

![A linocut print titled 'Kaiwalagal' depicting a male figure holding weapons and wearing a headdress in the centre, surrounded by representations of the High Court of Australia, a man holding a Native Title document, dwellings, animals, a man holding a gun, and two people in a canoe. The artwork is printed in black ink on cream coloured paper, with some sections coloured, particularly a shirt, fish and water coloured blue; a shirt, armbands and headdress coloured pink; plants and clothing coloured green; and a turtleshell, weapons, and sections of dwellings coloured brown. Annotations pencilled below the imprint read '1/10 Kaiwalagal DBosun / Solomon Booth [signatures]'.](https://www.nma.gov.au/__data/assets/image/0008/735695/Kaiwalagal-linocut-MA46597564.jpg)