The results of James Cook’s first Pacific voyage were many and far-reaching. Cook and the Endeavour voyage soon became triumphant emblems of the British Empire.

Emblems of the British Empire

The Endeavour left Australian waters in August 1770, arriving back in England in July 1771. Cook’s detailed navigational charts and observations, the botanical collections of Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, and the natural history drawings of Sydney Parkinson all brought this ‘new’ continent into the realm of Georgian England.

Matthew Flinders, 1814:

This voyage of Captain Cook, whether considered in the extent of his discoveries and the accuracy with which they were traced, or in the labour of his scientific associates, far surpassed all that had gone before.

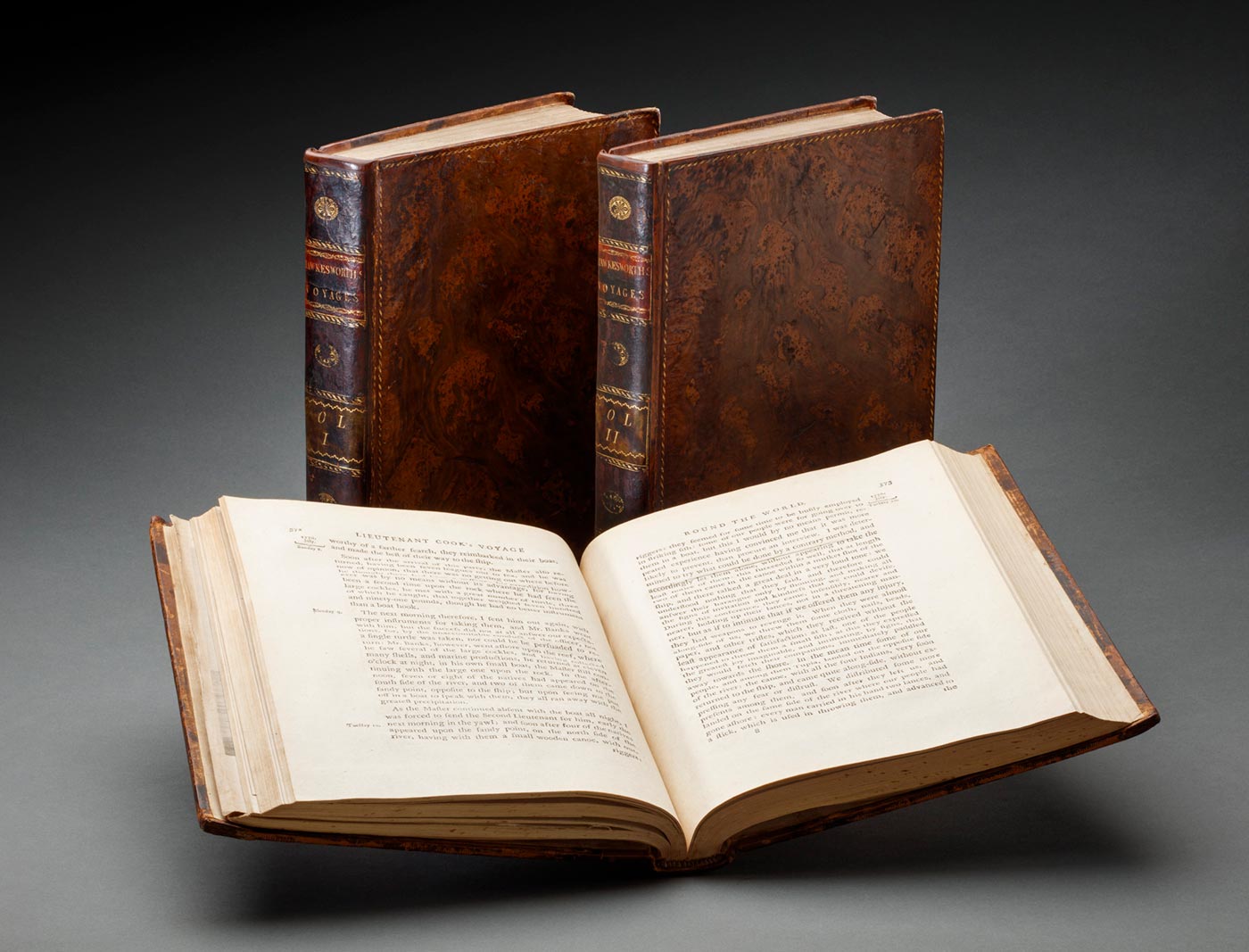

After the ship returned John Hawkesworth was commissioned to edit an account of the Endeavour’s voyage. It was soon published, although Hawkesworth embellishment of parts of Cook’s and Bank’s journals was controversial.

Cook’s fame quickly spread across Europe as readers devoured local translations of the voyage’s account. Marquis Jean-Joseph de Laborde, a wealthy French financier, was fascinated by the tales of Cook’s navigation and discoveries. He had a bust of ‘Jacques Cook’ made in the classical style. He installed it in his garden in 1788 in northern France as a memorial to Cook.

Biripi artist Jason Wing offers a different Cook bust:

I was taught that Australia was discovered by Captain James Cook. This colonial lie is further reinforced by a huge bronze sculpture in Hyde Park, Sydney, which is situated on a massacre site. Etched in stone are the words ‘Captain James Cook Discovered Australia 1770’. I feel physically ill every time I see this monument so I decided to create my own monument to Captain Cook, who personifies colonisation.

Seventeen years after the Endeavour had arrived back in England, the British return to Australia’s shores to establish a penal colony at Sydney Cove. This was the beginning of British colonisation of this continent. It also set off a catastrophic chain of events that continues to impact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people today.

Dr Jackie Huggins Bidjara/Birrigubba Juru:

We cannot deny our history. It’s a history that’s never fully been taught to us in our country. I know that when I went to school I learnt about the kings and queens of England long before I learnt about my people.

Cook portraits

Nathaniel Dance’s portrait is the most familiar image of James Cook. It was commissioned by Joseph Banks in 1776 and reflected the close relationship between the two men. Cook sat for the painting while in London between his second and third Pacific voyages. The portrait hung in Banks’s home in Soho Square, London, for many years.

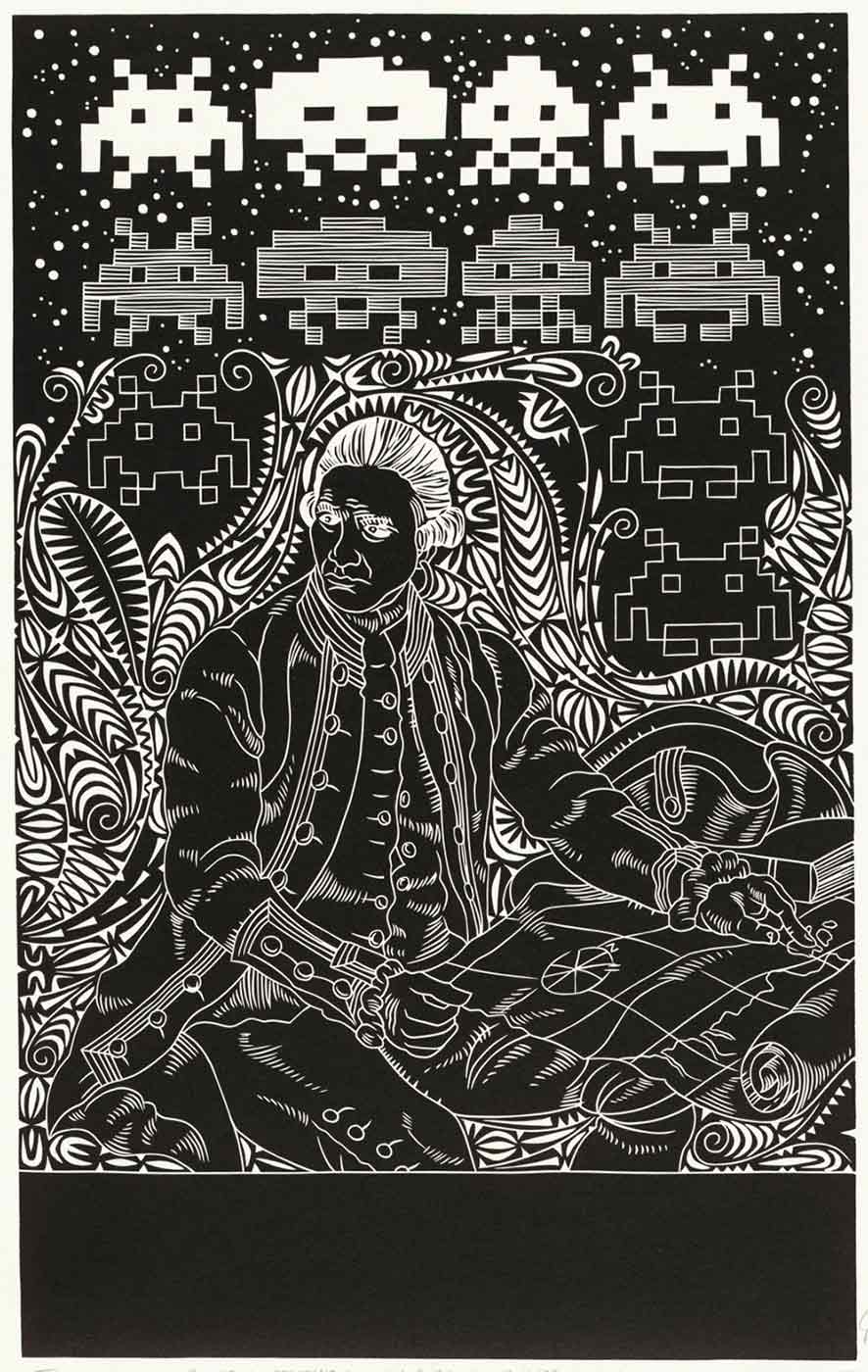

Inspired by Dance’s portrait and the 1970s arcade game Space Invaders, Torres Strait artist Brian Robinson created a new interpretation of Cook.

Stars of the show

JH Mortimer’s painting celebrates the success of Cook’s first Pacific voyage. Commissioned by First Lord of the Admiralty, John Montagu, it depicts three major figures on the Endeavour – James Cook, Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander – with Montagu and John Hawkesworth, who had just been engaged to edit the voyage’s official account. Cook (centre) pays his respects to Montagu and gestures in the direction of his next voyage.

Botany transformed

During the brief moments they were on shore, the Endeavour’s botanists worked quickly to collect the new plants they saw.

Back in England, Joseph Banks began the momentous project of making a complete record of his botanical collection. He employed artists to work with Parkinson’s sketches to create completed watercolour renditions. He then hired 18 master engravers to make 743 copper plates. The project continued for 13 years and cost more than £10,000.

Banks intended to publish the prints, but the final Florilegium was not produced until the 1980s. It has been described as the most important achievement in the graphic arts in the 20th century.

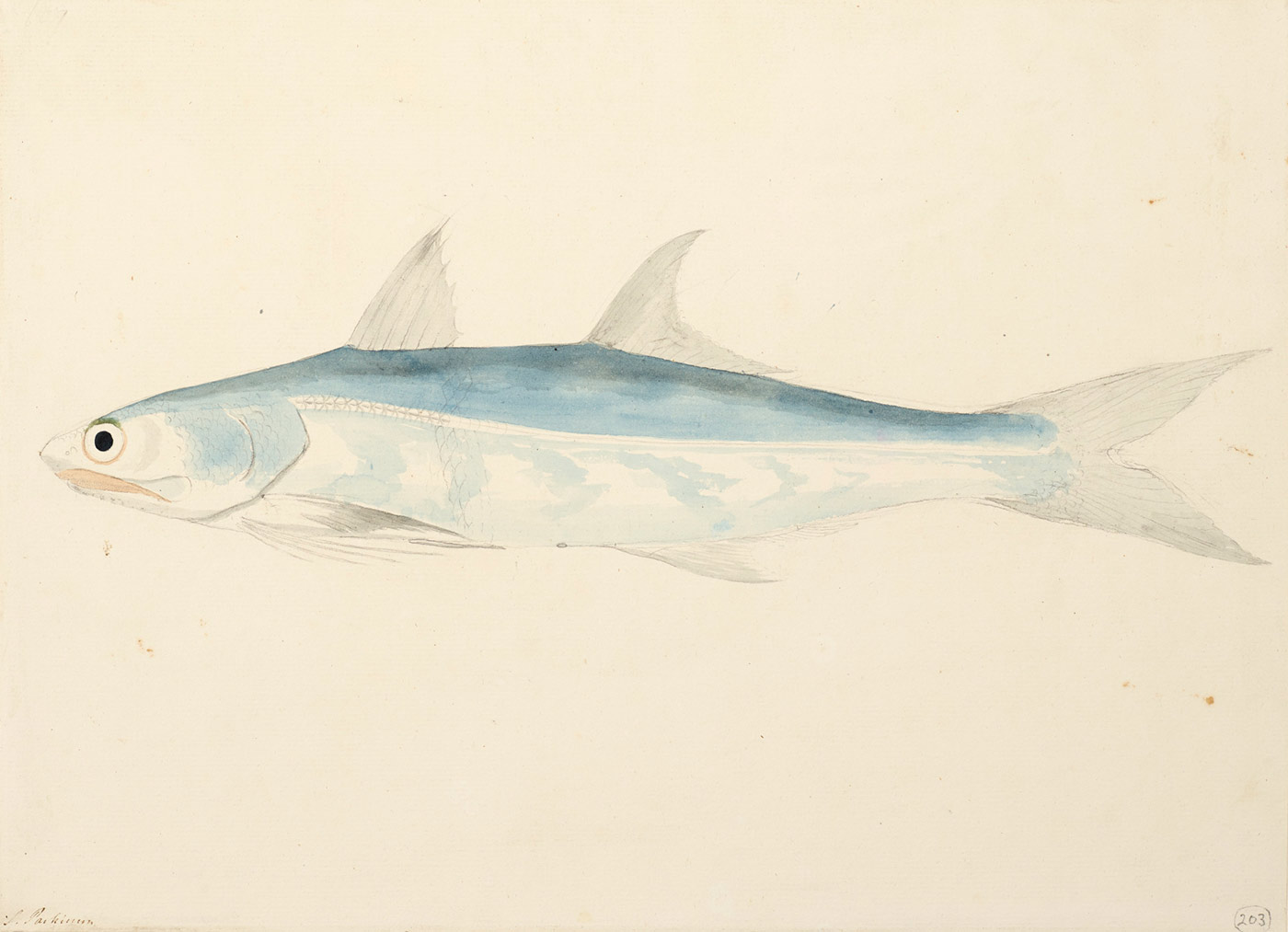

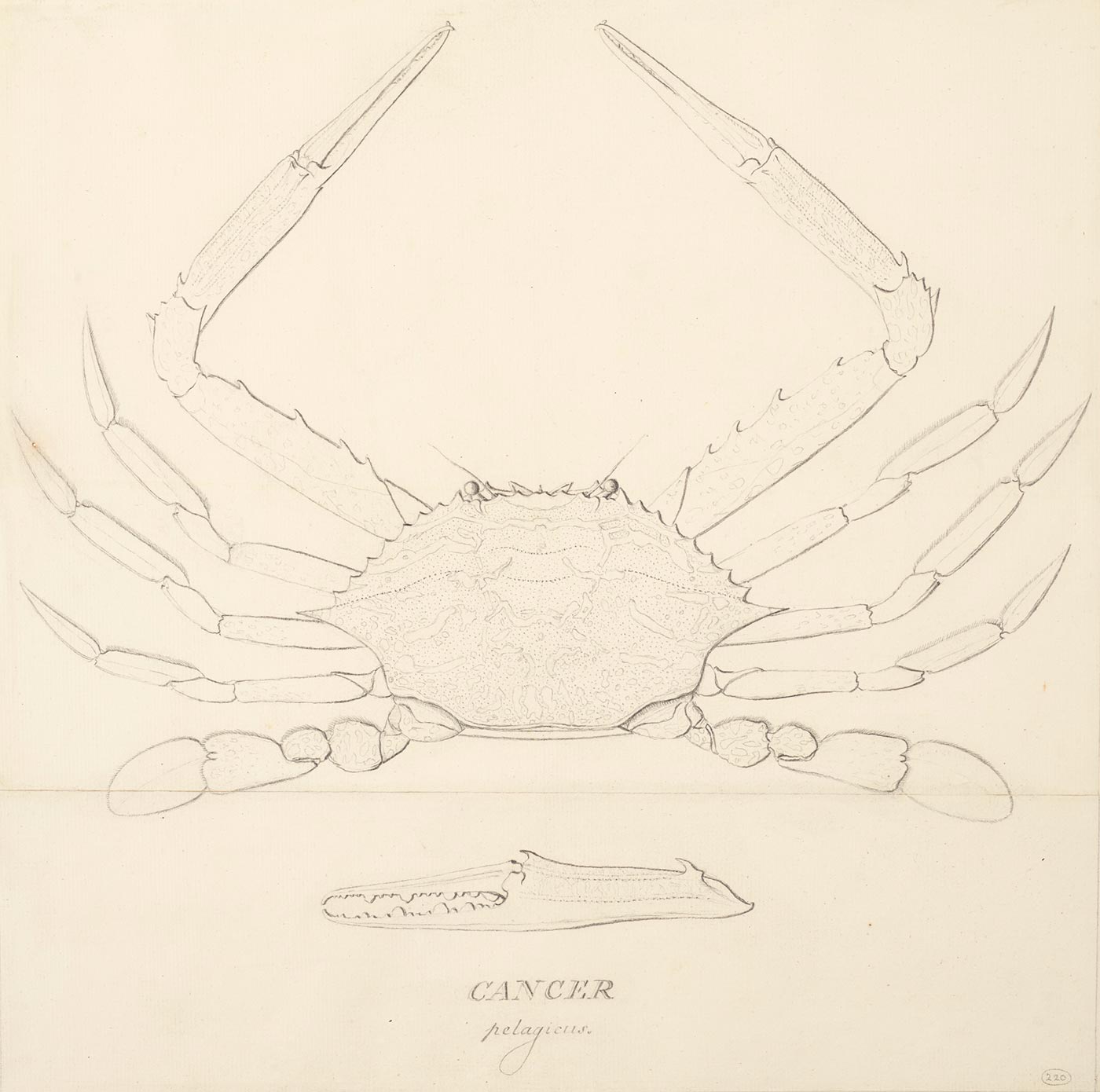

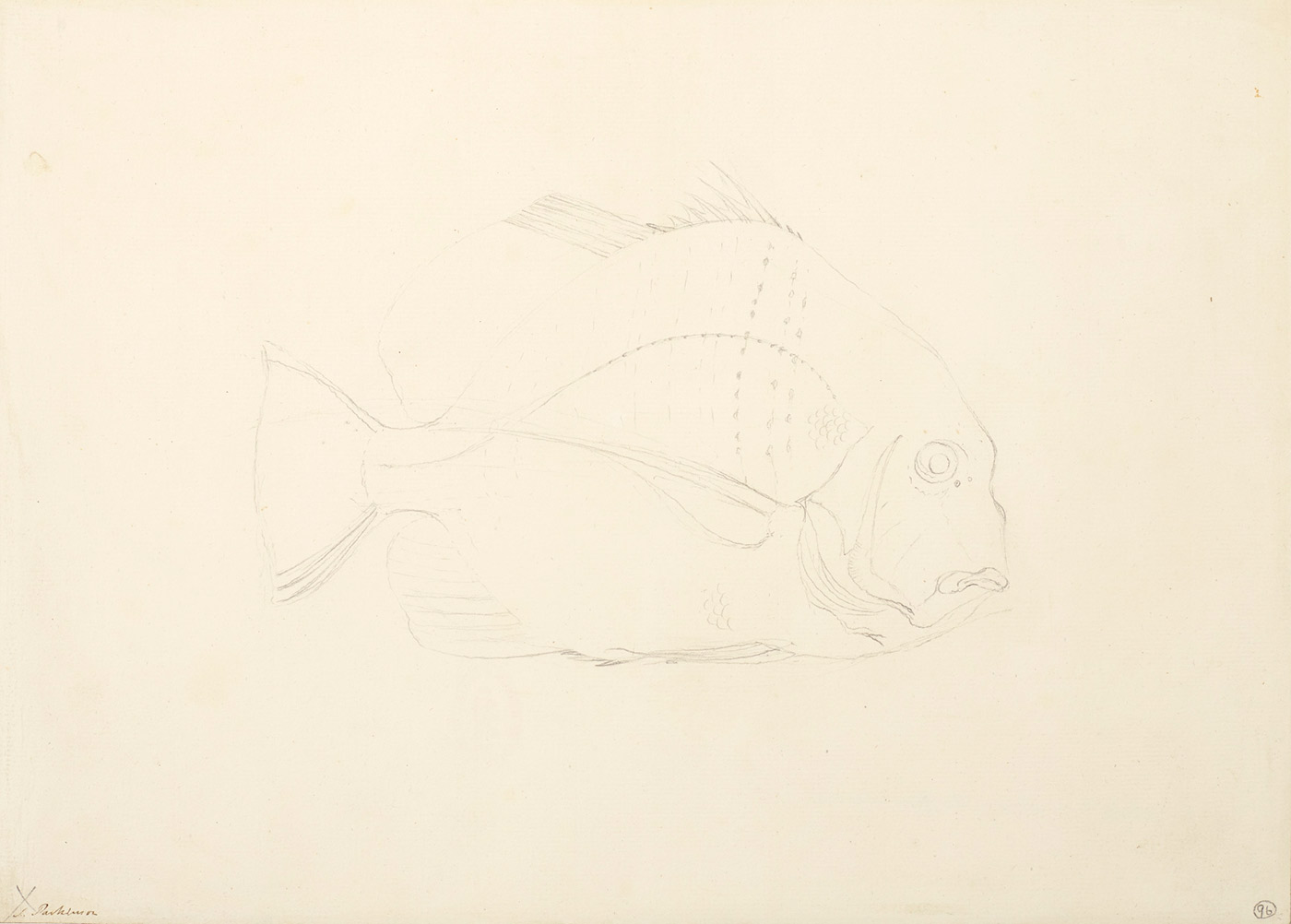

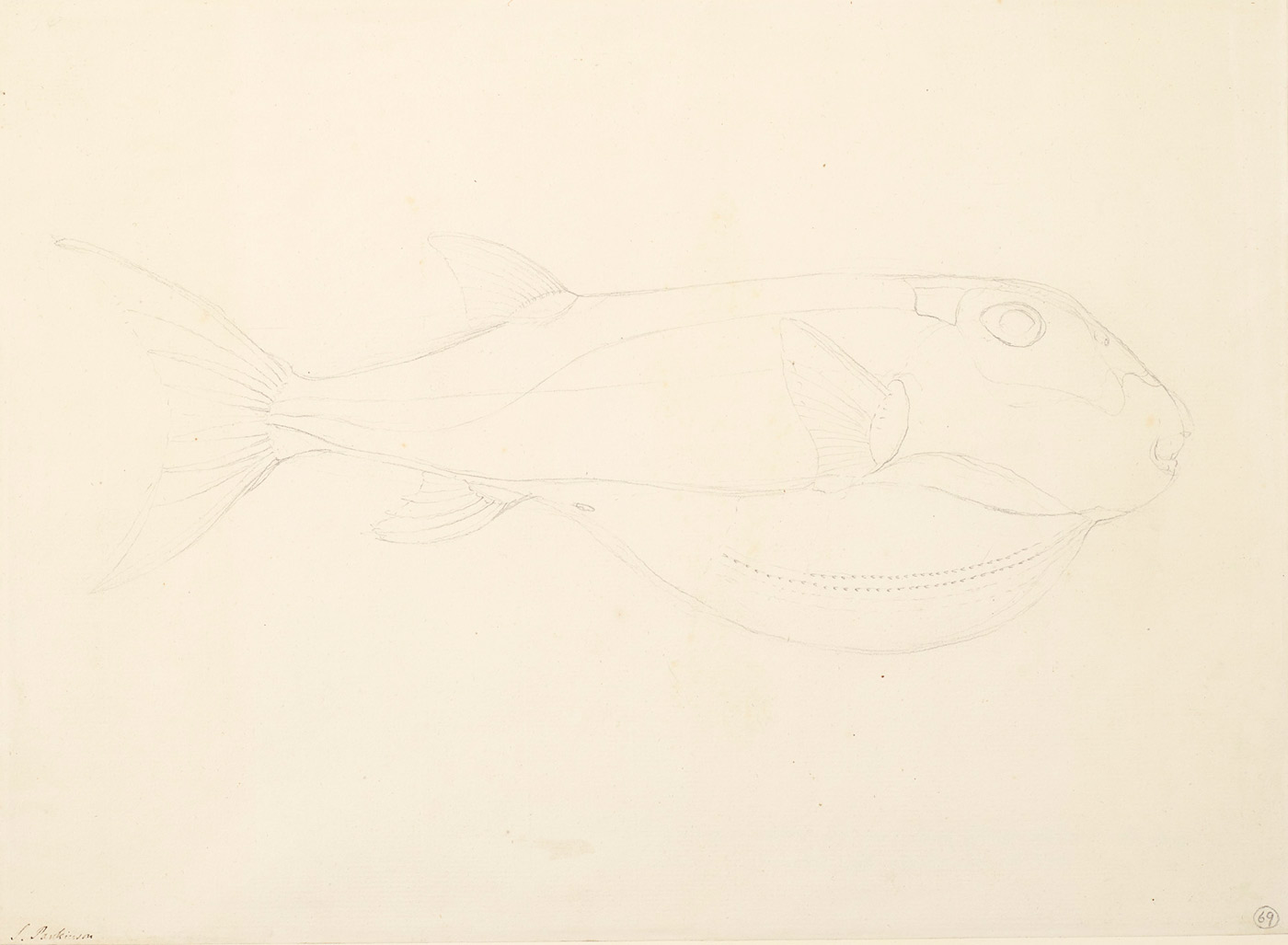

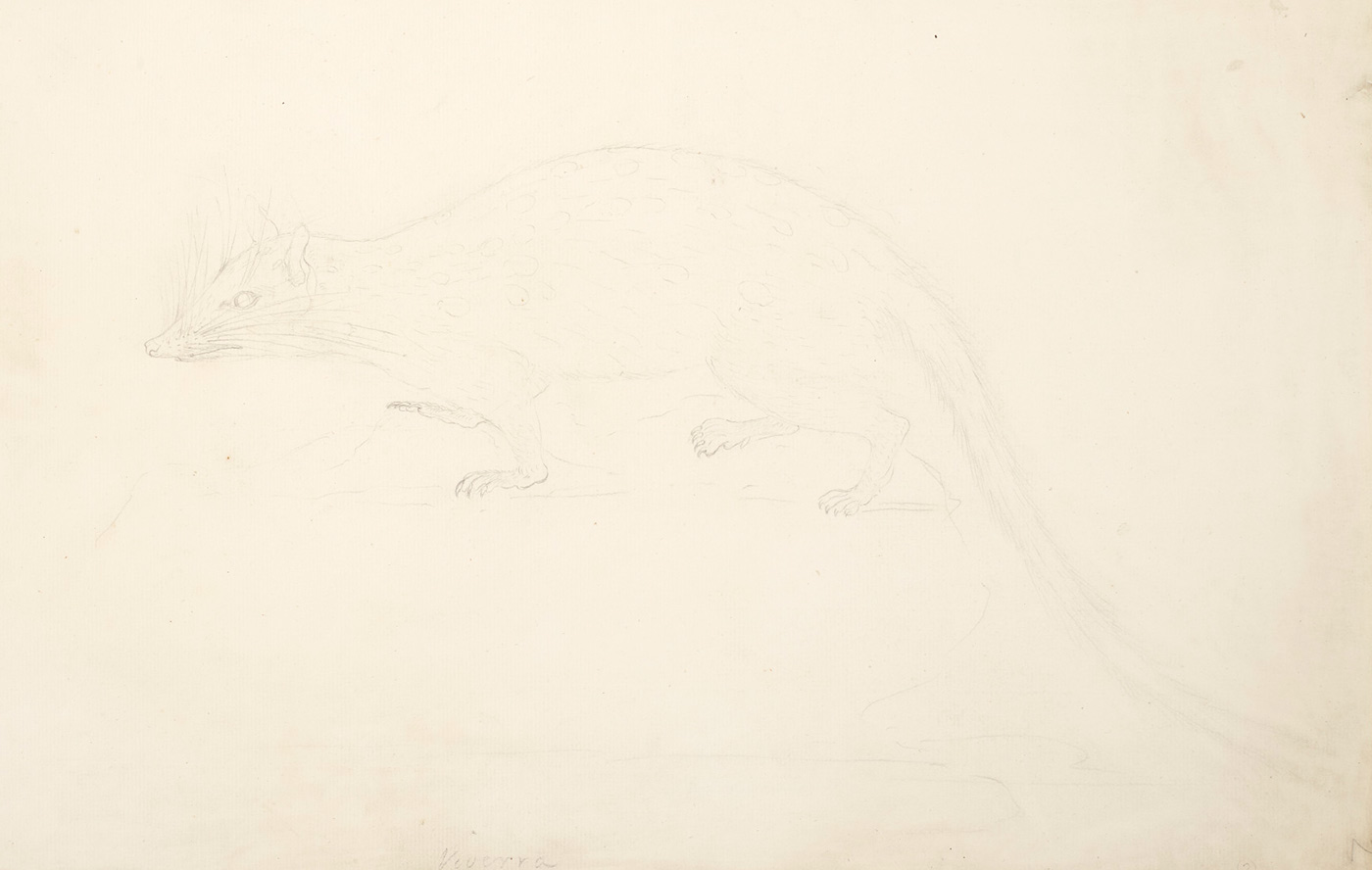

Parkinson sketches

As the Endeavour sailed across the Pacific, Joseph Banks and his team of naturalists ran a mobile laboratory on board the ship, recording the remarkable plants and animals they saw.

Part of their work was sketching and painting the ‘new’ species they collected. Because the voyagers spent most of their time at sea, many of these were aquatic species. Sydney Parkinson made outline sketches of their shape and recorded details of their colour.

Cooktown salmon or blue threadfin (Eleutheronema tetradactylum) from Endeavour River by Sydney Parkinson

Bluefin trevally (Caranx melampygus) from Tahiti by Sydney Parkinson

Crab (Portunus pelagicus) from Nova Cambria (New Wales) by Herman Spöring

Spotted sicklefish (Drepane punctata) from Endeavour River by Sydney Parkinson

Half-smooth golden pufferfish (Lagocephalus spadiceus) from Endeavour River by Sydney Parkinson

Northern quoll (Dasyurus hallucatus) from Endeavour River by Sydney Parkinson

Hawkesworth's account and the stuff of legend

The Admiralty commissioned John Hawkesworth to edit the official account of the Endeavour’s voyage and he secured a £6000 advance from his publisher. Hawkesworth had not been on the ship, so he used the journals of Cook, Banks and others as sources.

Banks criticised Hawkesworth for embellishing events, particularly the crew’s activities in Tahiti. But the book was an immediate bestseller, ensuring Cook’s reputation and helping legitimise Britain’s territorial claims in the Pacific.

A terrestrial globe produced in 1772 shows how quickly the information that Cook brought back entered the public realm.

Stitching the voyage

A young Englishwoman embroidered the map sampler pictured below. The carefully inked letters record the milestones of Cook’s three journeys, showing the maker had read the wildly popular accounts of his voyages. She may not have read the Australian chapters closely – the positions of ‘Botany Bay’ and ‘Port Jackson’ are swapped on her map.

Child’s play

Robert Davidson, Elements of Geography, 1787:

How can a boy or a man know the excellence and glory of his own country ... without some knowledge of geography? ... Persuade your parents to reward your diligence with a dissected map.

In 1813 John Wallis made a jigsaw featuring the routes of Cook’s three Pacific voyages to sell at his Instructive Toy Warehouse in London. Puzzles like these ensured that the grand story of Cook and Britain’s influence over the world entered children’s playtime.

Elizabeth Cook

We know little about the life of Cook’s wife, Elizabeth, during the long years her husband spent at sea.

In 1780 she was sewing her husband a waistcoat, made from tapa cloth that Cook had collected on an earlier voyage. She was making it for him to wear when attending royal events at court.

The coat remains unfinished. Elizabeth put it aside after she received the news of her husband’s death in Hawaii in 1779.

Elizabeth survived her husband by 56 years and outlived all their six children.

See the waistcoat on the State Library of New South Wales website

Cook’s death

Cook was killed at Kealakekua Bay, Hawaii, in February 1779. It was his third visit to Hawaii. He was weary from 10 long years at sea and relations between the Hawaiians and Cook’s crew had soured. A violent confrontation ended in the death of Cook, four marines and dozens of Hawaiians. In the following days, many more Hawaiians were shot and killed.

News of Cook’s death reached England in January 1780, nine months before his ships returned. Cook’s death shocked the European world. Pictures imagining his final moments soon appeared, and Cook took on mythic qualities, elevated beyond an ordinary mortal. The Hawaiians at Kealakekua Bay saw it differently.

Remnant of an encounter

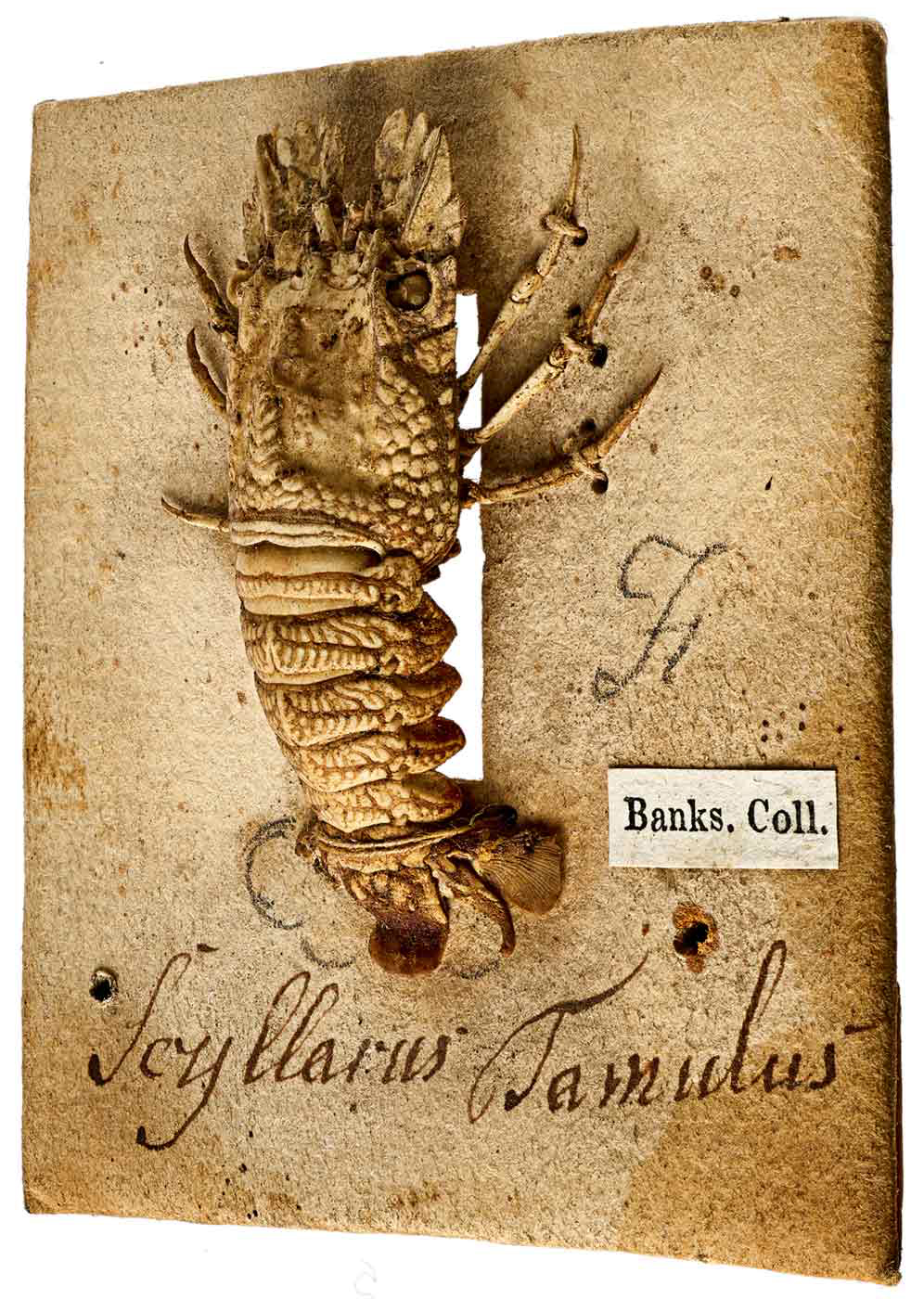

After the Endeavour returned to England, and before Cook’s second Pacific voyage, Joseph Banks had a series of medals made for future voyagers to hand out to Indigenous people that they met and traded with.

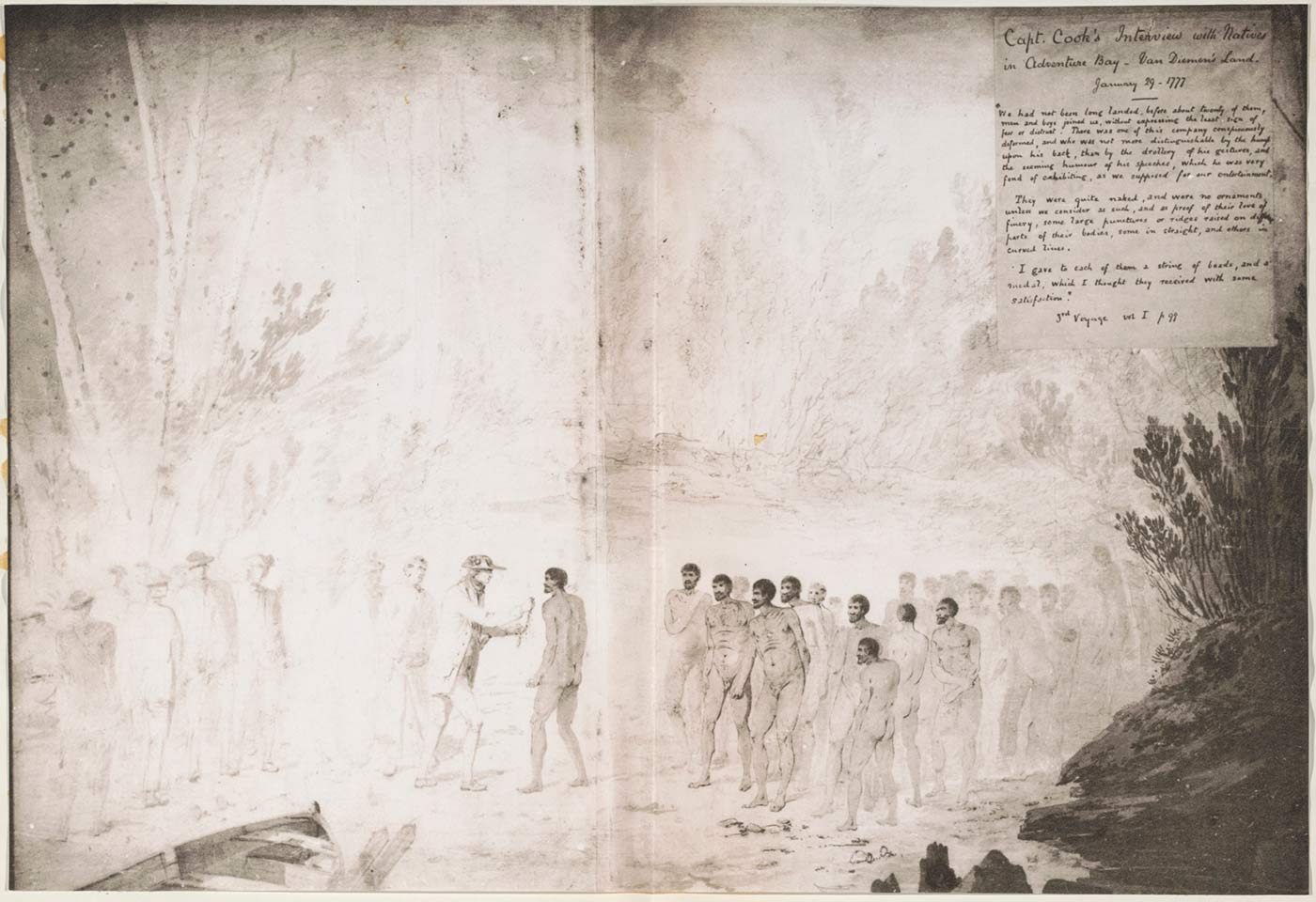

Four-year-old Janet Cadell found one of these in 1914 on her father’s farm on Bruny Island, Tasmania. It remains the only medal from Cook’s voyages to be found in Australia. Cook had given it to Aboriginal people at Adventure Bay, Van Diemen’s Land, when he stopped there during his third Pacific voyage in 1777.

James Cook, 29 January 1777:

I gave each of them a string of Beads and a Medal, which I thought they received with some satisfaction.

Nothing unattempted

After Cook’s death in 1779, the Royal Society commissioned a medal honouring him and his achievements. These were issued to subscribers: 22 were gold, 322 silver and 577 bronze.

A translation of the medal’s Latin inscription reads:

James Cook the most intrepid investigator of the seas’ and ‘Our men have left nothing unattempted.

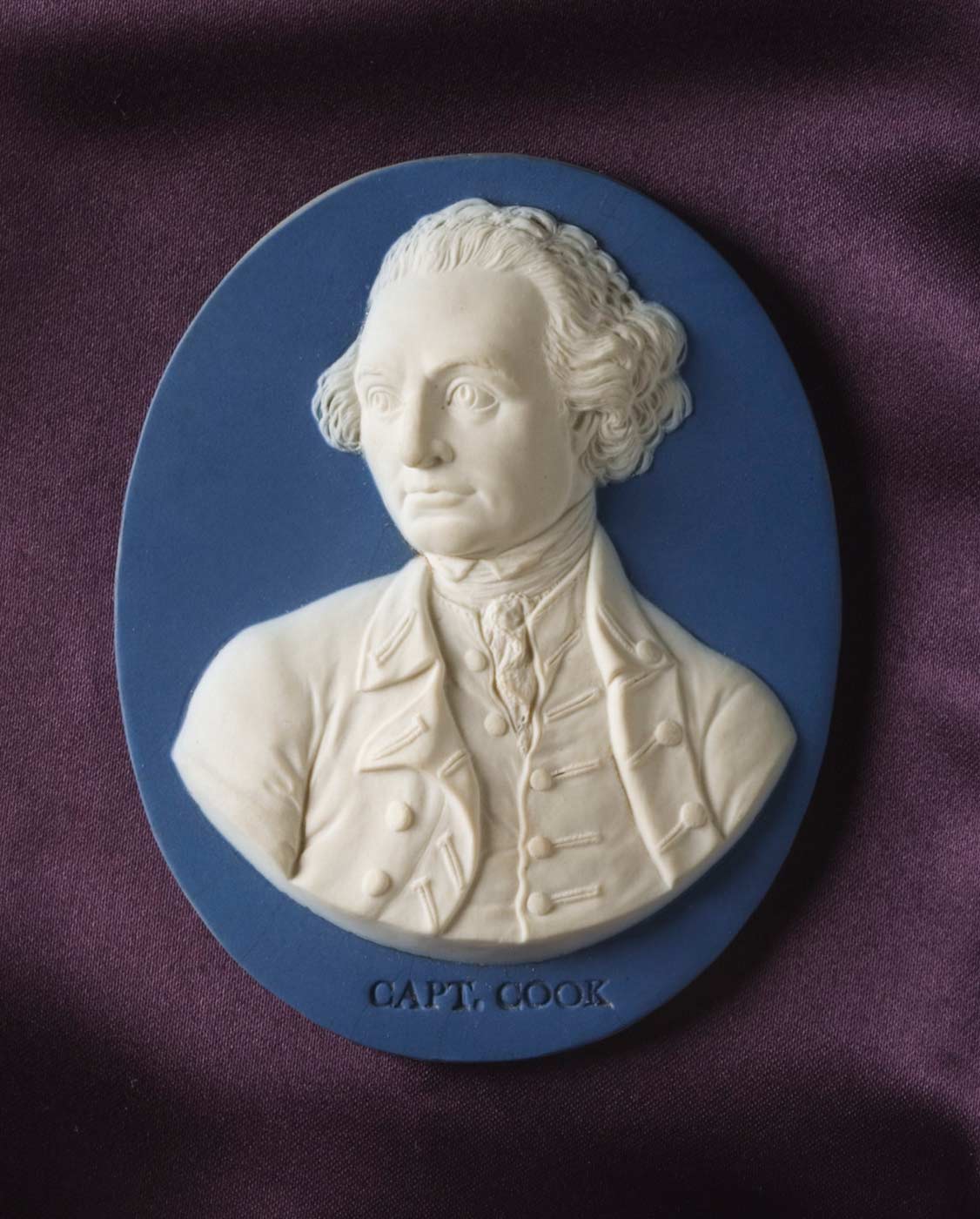

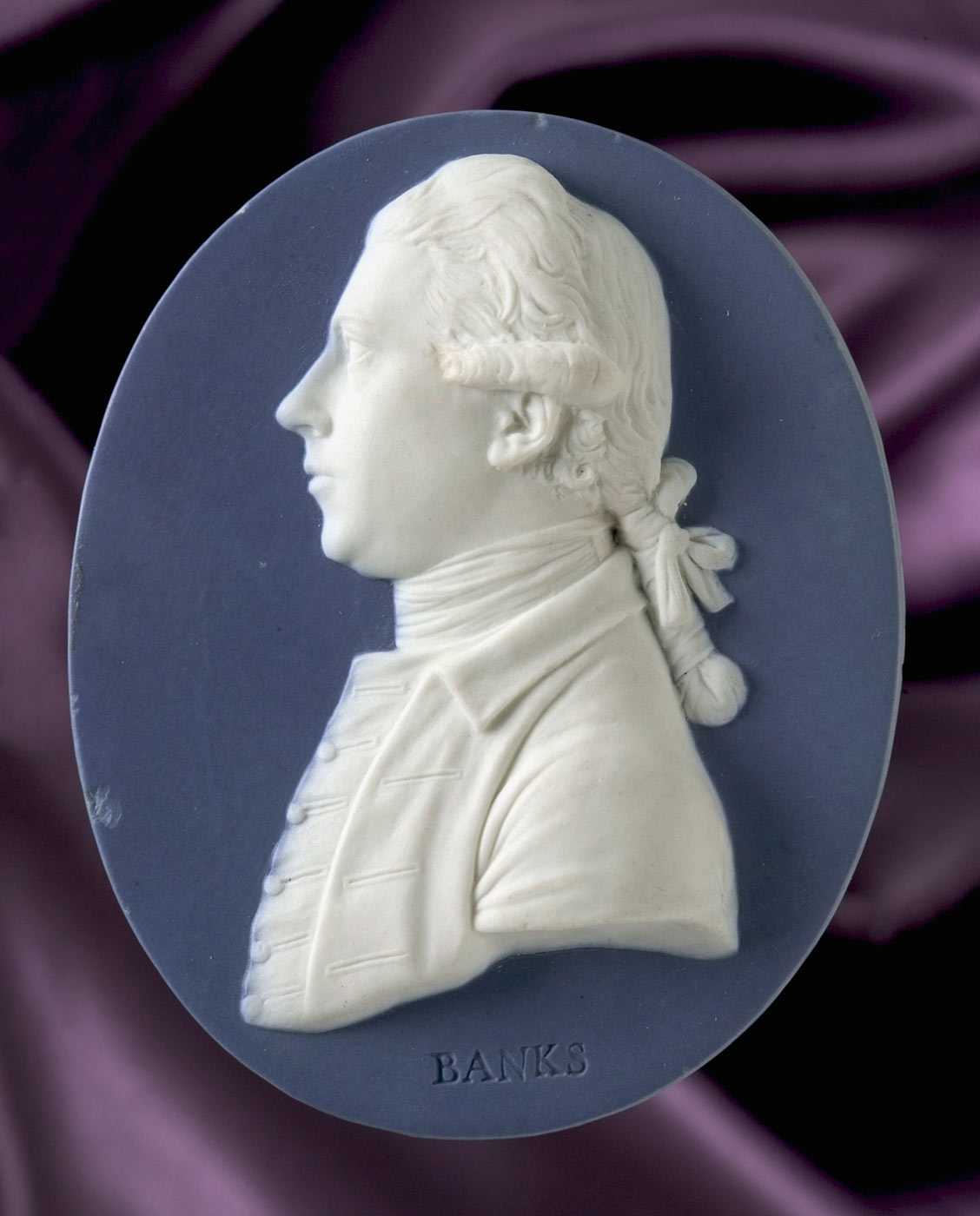

Fixed in clay

The achievements of Cook and the Endeavour’s scientists were quickly celebrated as an important part of Britain’s claim on the Pacific.

Soon after the ship returned to England, Cook, Banks and Solander featured in a series of expensive celebrity portrait medallions made by Wedgwood pottery. The three Endeavour voyagers found themselves in the company of the most illustrious scientists, philosophers, doctors and statesmen of the day.

Representations of Cook were not confined to the drawing rooms of the wealthy. This Pratt Ware portrait of Cook probably hung on the wall of a rural British home in the 1780s. Mass-produced from glazed earthenware, it was a cheaper version of the Wedgwood portrait medallions favoured by the well-to-do.