We are alive, the land is alive

Carol Christophersen, Muran, 2014:

The raindrops and the streams are the tears and the blood of the land. The texture of the stone is the texture of our skin. We are alive, the land is alive. No colonial power can ever rob us of this.

It was Aboriginal people around Port Jackson who first experienced the effects of British rule on this continent.

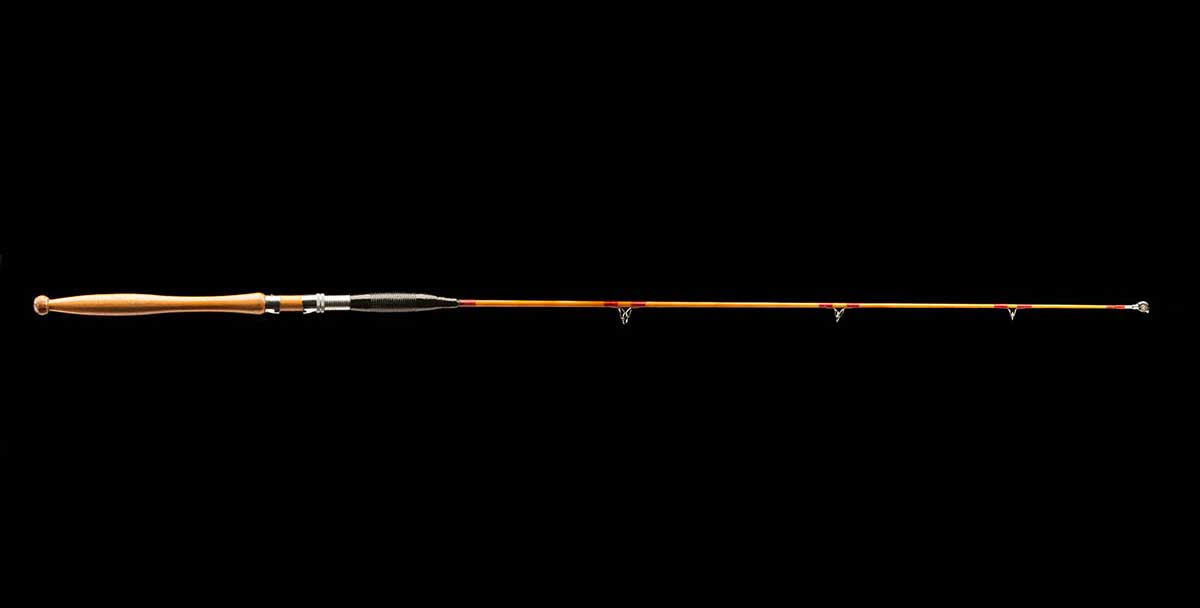

Ralph Mansfield – the likely collector of hunting and fishing implements, including the fishing line pictured below – lived in Sydney from 1825 and was editor of the Sydney Gazette. He witnessed firsthand the effects of the disease, violence and social dislocation that accompanied British colonisation.

Acquired during the early days of British settlement, the objects throw a different light on colonial times. As artefacts of hunting and fishing, they reveal lives lived in country. Gai-mariagal and other Sydney Aboriginal people still fish in Sydney Harbour.

Old objects

In 1834 George Annesley, second Earl of Mountnorris, commissioned Sydney resident Ralph Mansfield to acquire Aboriginal objects for his private collection. We think that this fishing line was among items collected by Mansfield.

Noted collector Henry Christy bought them at an auction of Annesley’s estate in 1852. Christy, who died in 1865, bequeathed his private collection to the British nation and it later became part of the British Museum’s collections.

New objects

Janet Wilson, 2014:

I don’t think [Mary Bundock] particularly thought that she was collecting for a museum. In a sense she was collecting to look after the stories of the people that she loved. I think that was a terrific thing, and we should be really proud of that.

You may also like