One place, two histories

Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Cultural Centre, 2015:

The elders call their people to one place so they listen and learn the stories, songs and dances that connect them to the land. They direct evidence of people’s right to live in this country through their corroborees. They make people feel strong and proud.

The Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Cultural Centre hosts a biennial festival to promote the richness of Kimberley culture and celebrate living in country for more than 20,000 years. The final years of the 19th century, however, were defined by violence, as colonists advanced into Kimberley Aboriginal country.

Neil Carter, Gooniyandi and Kidji, 2013:

Our culture has been not devastated – it is still here – but interrupted.

The objects from that time are inevitably caught up in conflicting understandings of the Kimberley. British collectors saw the region as a place with a remarkable but dying culture; Kimberley Aboriginal people understand this time very differently.

June Oscar, Bunuba elder, 2015:

We know that each object displayed ... has conjured a range of contradictory emotions for Indigenous people ... joy and wonderment at our remarkable living cultural heritage, and pain, outrage and resentment emanating from the colonial wars ... that saw countless violent deaths causing profound cultural and societal loss and intergenerational grief ... I know those emotions firsthand; I have been part of this exhaustive and meaningful journey every step of the way.

Old objects

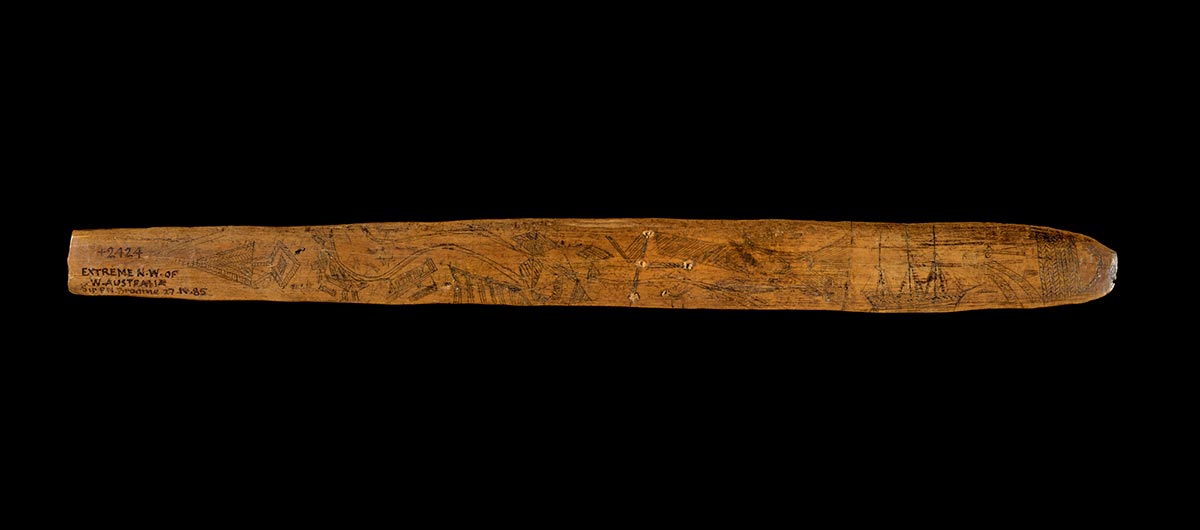

Message stick

Among the things collected, and now in the British Museum’s collections, is a message stick (above) that Sir Frederick Napier Broome, Governor of Western Australia, acquired during a visit in 1884 to the towns of Derby and Roebourne, and to the Yeda and Liveringa pastoral stations.

The message stick was among 13 Aboriginal objects Broome donated to the British Museum during a return visit to England in 1885. Message sticks intrigued Lady Mary Anne Broome, the governor’s wife. She describes this one in her 1885 book Letters to Guy:

Perhaps the ‘message sticks’ are the most curious, with their smooth surface of which all the news of the place is neatly and carefully drawn ... it really is the newspaper of the district.

You see ... two or three rude houses which constitute the nucleus of what is going to be a great city, perhaps ... an unmistakable bit of a harbour, and the fleet of pearlers is just coming in ... There are some trees ... men stand by an open grave, horses are picketed behind, and there is a rude cross in the corner.

New objects

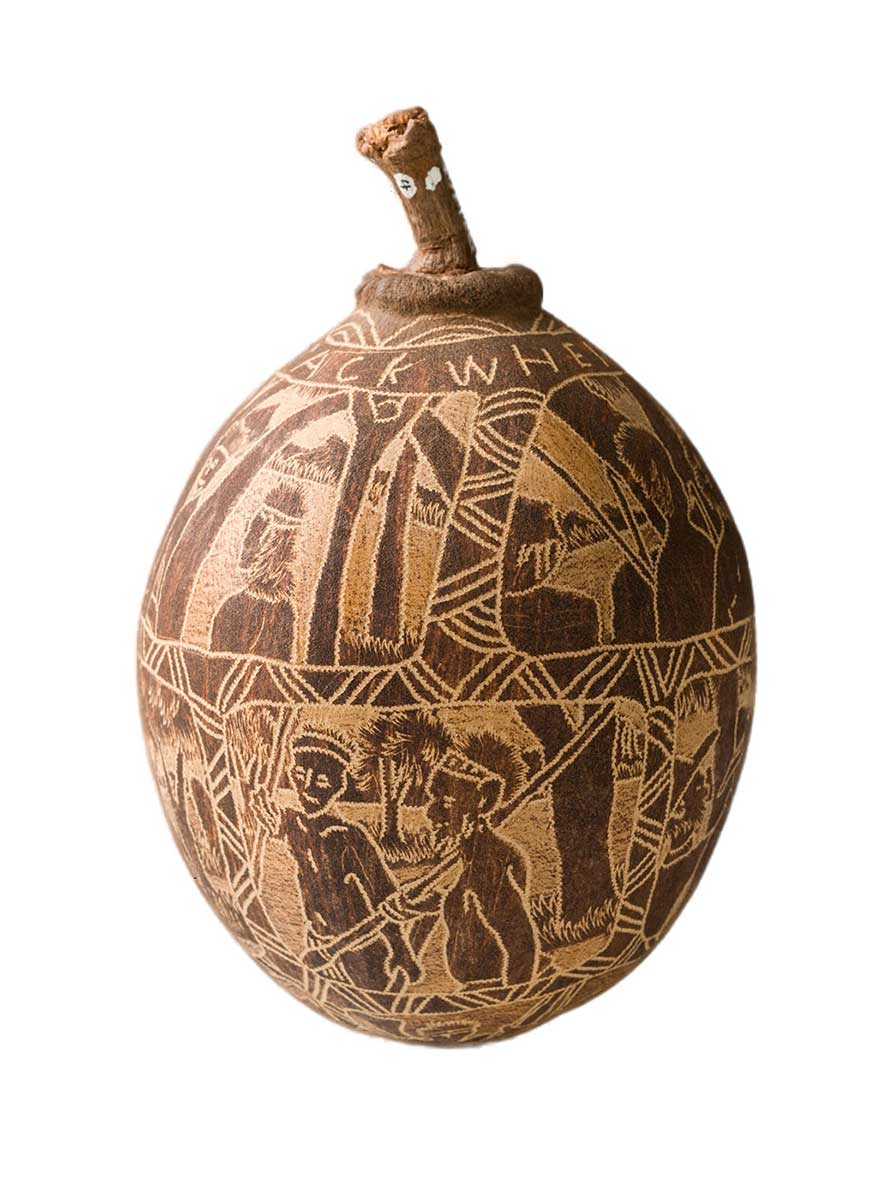

Carving history

Jack Wherra was a renowned carver and artist from the Kimberley region. During the 1960s he depicted his version of Kimberley history in a series of engraved boab nuts (above). His style was influenced by the comics he read while serving time in Broome Gaol.

Some of Wherra’s carvings reflect his interpretation of the violence that was a part of the frontier in the north-west. Two of those pictured here depict Aboriginal people attacking cattle and stockmen. The third shows the changes brought by British settlers, in a scene where police become involved in a traditional dispute over a woman.

Making a message

Joe Brown, Walmajarri lawman, 2015:

The marking ... everything gotta meaning.

You may also like