We leave them where they lie

Canberra is the host city for the Encounters exhibition. It is also country that has been home to Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri peoples for more than 20,000 years. Some of their stone tools from Canberra’s Mount Ainslie are now in the collection of the British Museum.

The stone scraper (below) travelled from Mount Ainslie to London and back for the exhibition – a long journey, through time and space. The custodians of this place reflect on the meaning of country today.

Old objects

William Kinsela collected this stone scraper during a visit to Canberra in the 1930s. He described his search for artefacts in an article in the journal Mankind, in 1934: ‘[I] had to search diligently to locate the site of any old camp or ‘workshop’ ... either close to creeks and rivers or in the sheltered parts of the hills’.

This scraper is among a few flaked implements he found near Mount Ainslie, ‘showing careful workmanship of secondary finish. Several 'crescents', 'thumb nails', plain scrapers and scarifiers or 'points' were interesting types, but they needed tedious searching to locate’.

He sent the scraper, with some other objects, to the British Museum in 1934, with a request that they be exchanged for ‘several small type specimens of English or Continental stone implements of paleolithic man’.

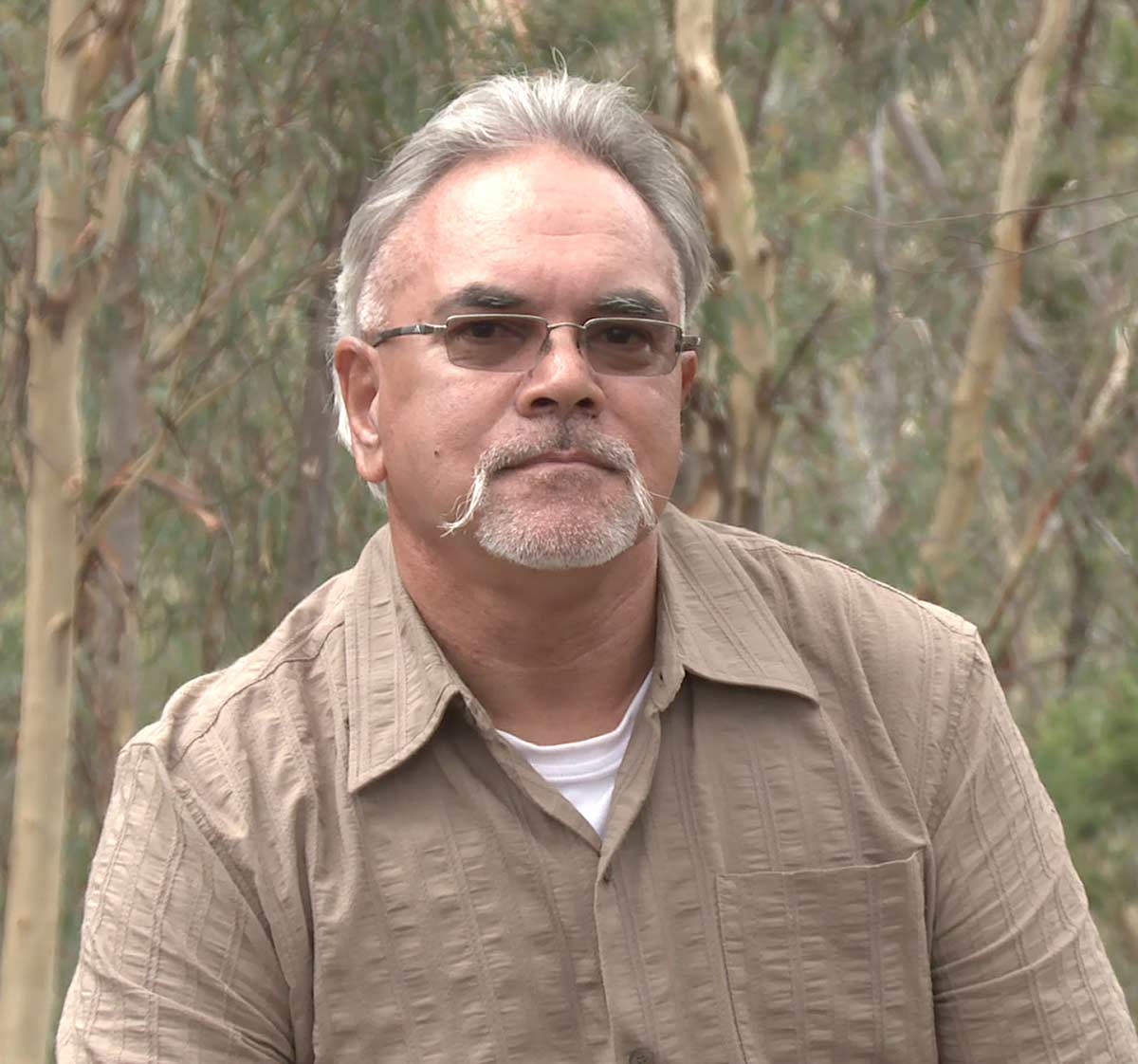

Adrian Brown, Ngunnawal, 2014:

Stone tools are all over the Canberra regions. They are pieces of country. We leave them where they lie so they will continue to be part of Ngunnawal country.

New objects

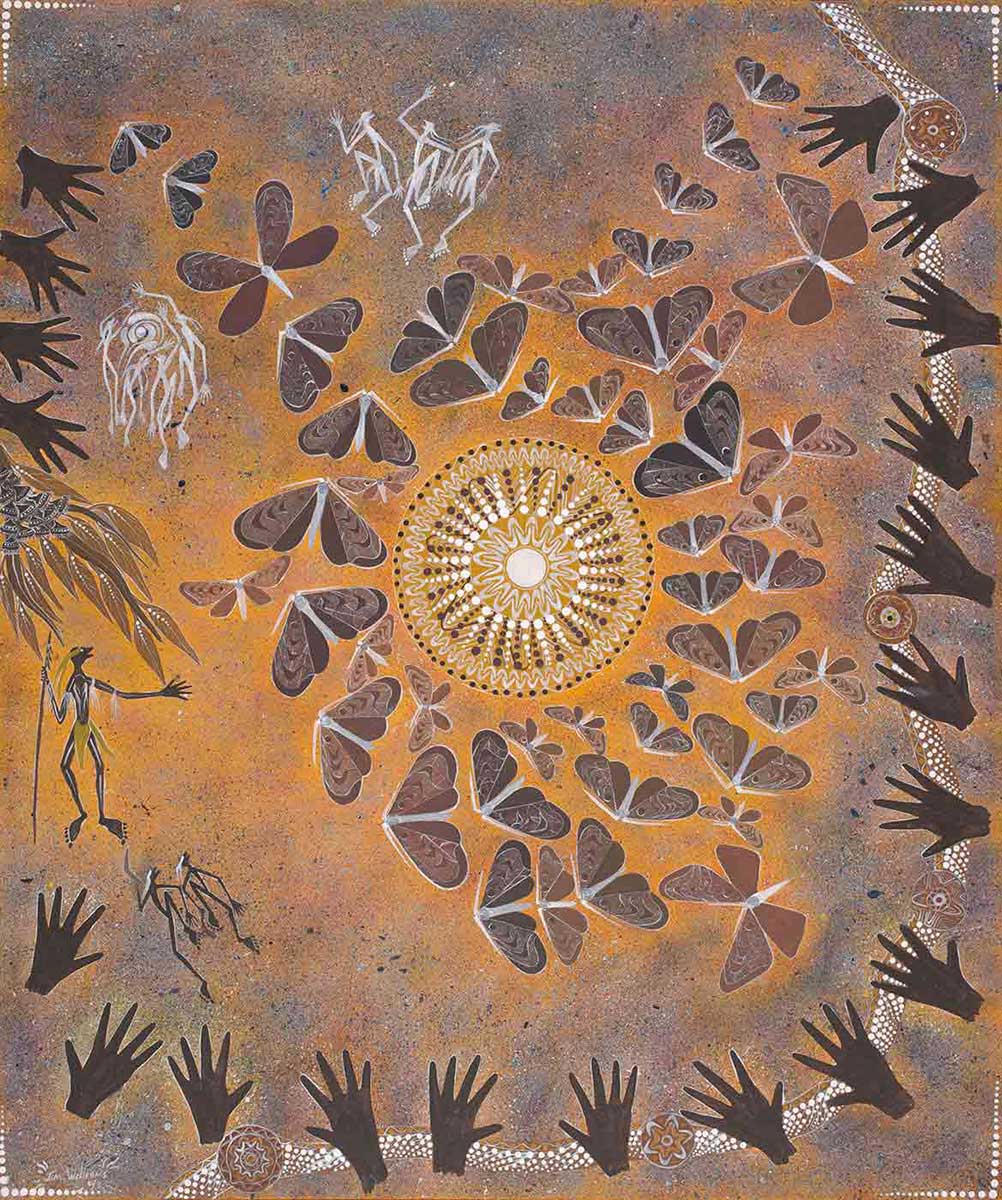

My Country, Ngunnawal Country, 2015

Adrian Brown, Ngunnawal, 2015:

These are the colours of my country. Every stroke in the painting has meaning and connects to that part of my country. The clapsticks are significant because that sound resonates out, calling people, connecting my spirit to country and to ancestors.

Mulanggang (platypus), 2015

Wally Bell, Ngunawal elder, 2015:

Our culture is a living culture that’s still developing and growing within itself. We’re learning every day still. As time progresses things are changing. We’re always learning to be adaptable to those changes ... Aboriginal culture is not stagnant like most people think it is.

Kicked out of Parliament, 2003

For thousands of years, Ngambri people have gathered in the high country near Canberra each summer to celebrate the arrival of the bogong moths on their migration south.

Attracted by the cool of the mountain climate, moths in their millions seek shelter in rocky crevices and overhangs. Providing an important seasonal food for the Ngambri and other peoples, they were collected in nets and roasted on fires.

Despite graziers and settlements impeding the movement of Ngambri people across the region, thousands continued to gather in the high country during the bogong season.

William Kinsela, 1933:

Among the hills near Mt Ainslie, at Canberra, [I] collected a few ... flaked implements, showing careful workmanship of secondary finish – Perhaps after six hours careful hunting on one site the reward might only be twelve artifacts.

You may also like