In late 1922 the esteemed Australian artist Tom Roberts and his wife Lillie Roberts were packing up their north London home to return to Australia after a 20-year sojourn in England.

Yes we are in it; dust, muck, junk. Old broom handles, tins rusty, card boxes (will be so useful to you my dear) papers. a bottle of bitter. Correspondence of years. Post cards.

Sketches to fire away – Ambitious canvases begun – fire – Cleansing fire wipes the devils out.1

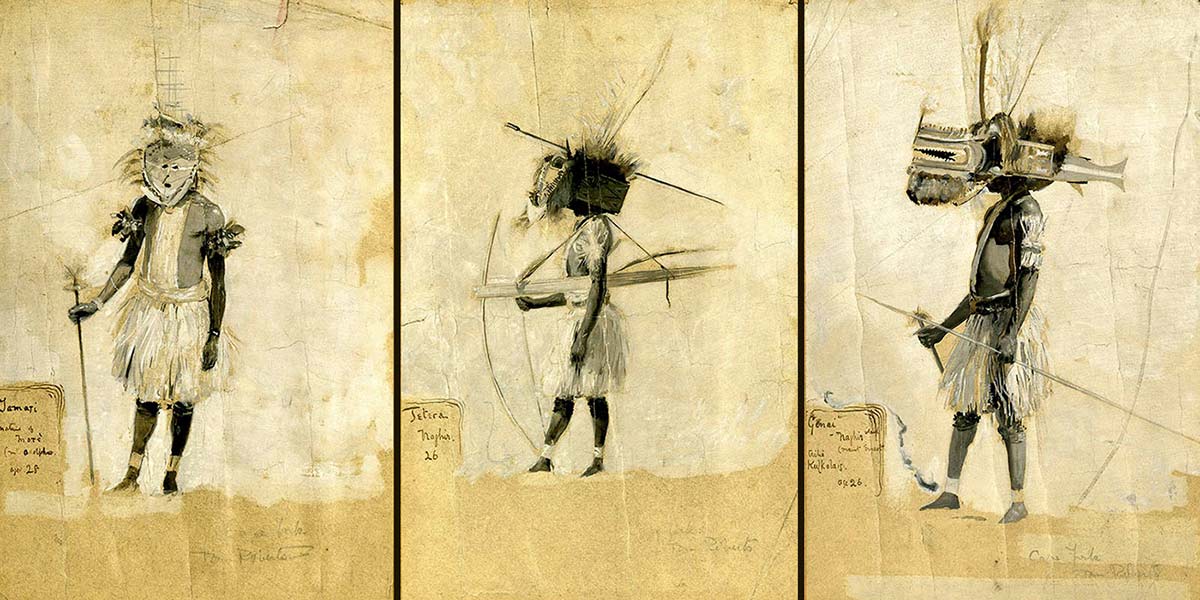

Among their possessions were mementos of a brief trip Roberts had made to the Torres Strait 30 years before. These included 3 gouache portraits of Torres Strait Islander men at Somerset, Cape York, wearing elaborate headdresses, a larger gouache work depicting a night-time ceremony Roberts had witnessed on Mer (Murray Island) and 18 ‘ethnographic’ objects from the Torres Strait.

Like many of the Indigenous things featured in the Encounters exhibition, research brings to light the complex worlds that these objects are connected to.

The couple had kept these paintings in their home for many years, taking them to London in 1903 when Tom was completing The Big Picture – his famous depiction of the opening of Australia’s first parliament. On the eve of their final return to Australia, this was a time to sort through their possessions, to let go of things; and in August 1922 Roberts donated both the paintings and the objects to the British Museum.

Roberts’s donation was overseen by Thomas Joyce, Deputy Keeper in the British Museum’s Department of Ceramics and Ethnography. Joyce had firm views about which objects were appropriate for the museum’s collections, and a clear view about the purpose of this material:

… from a museum point of view, old & used specimens are the most valuable … we have no use for objects manufactured 'for sale' by the natives; the purpose of the national museum is to show as far as possible the native method of life of the tribes that Britain controls.2

The museum’s interests would have been primarily in Roberts’s ethnographic objects, and in placing the four artworks in the Department of Ceramics and Ethnography rather than the Prints Department, Roberts would have been aware that the artworks were being accepted primarily for their ethnographic significance, rather than their aesthetic value.

His collection of this material, and his taking it back to England, and his retaining it for some 30 years suggests his strong attachment to it – whether for its ethnographic interest or as souvenirs of his experiences in the Torres Strait, or both. It suggests that the trip north continued to resonate with him.

Today, as well as their importance for Torres Strait Islander communities, these powerful artworks also shift our understandings of Roberts life and work.

You may also like