In August 1963 two bark petitions were presented to the Australian Parliament’s House of Representatives. This was a formal attempt by the Yolngu to have their land rights recognised.

It was also the first time documents incorporating First Nations ways of representing relationships to land were recognised by parliament.

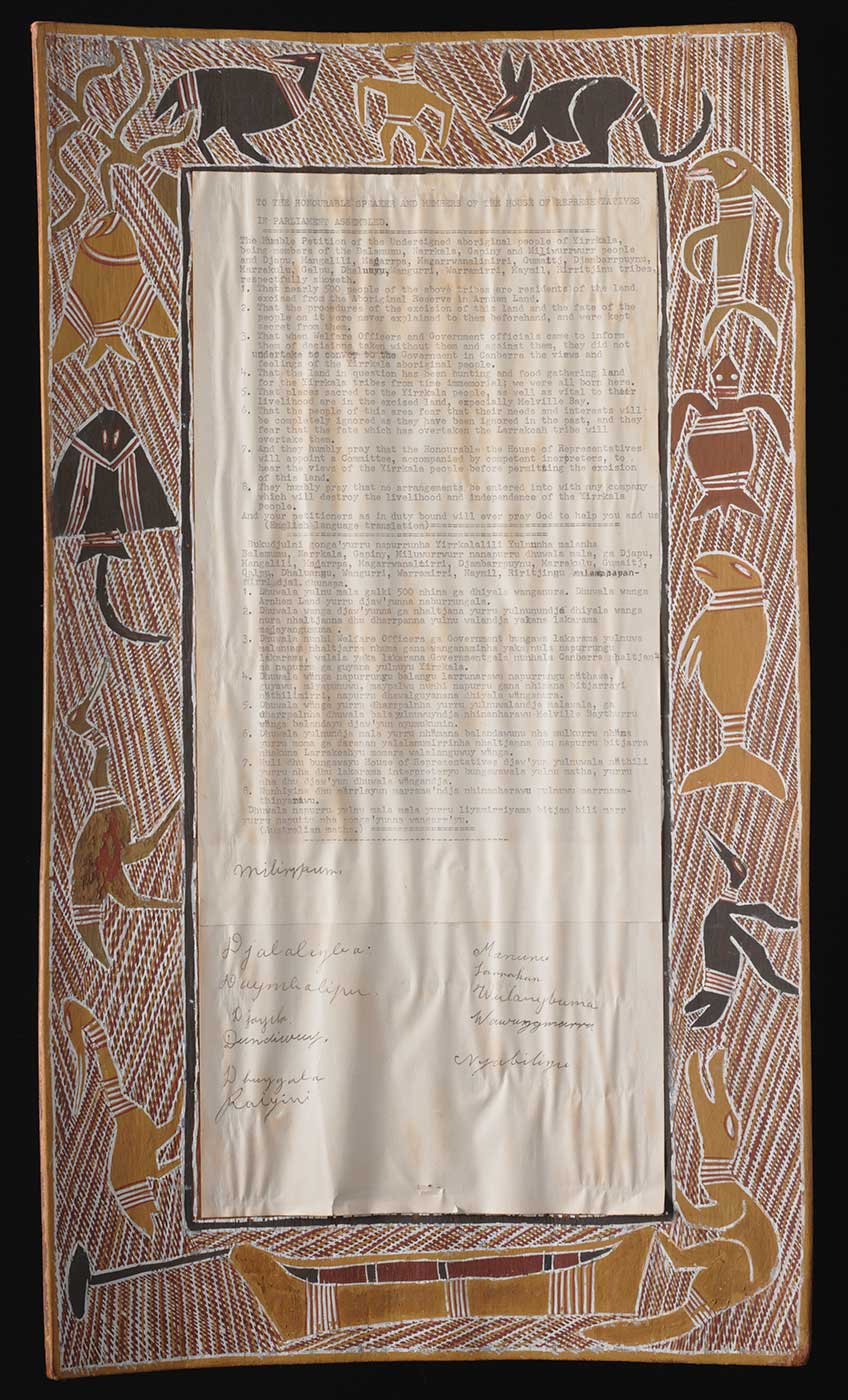

Extract, Yirrkala bark petition, 1963:

… the people of this area fear their needs and interests will be completely ignored as they have been ignored in the past …

The Yolgnu and Arnhem Land

First Nations people believe they have lived in the area we now call Arnhem Land ‘since time immemorial’. Aboriginal people from central and eastern Arnhem Land call themselves Yolngu, which means ‘people’ or ‘human being’ in Yolgnu Matha language. One of the largest Yolngu settlements is Yirrkala, about 700 kilometres east of Darwin.

The Arnhem Land Reserve was established by the Australian Parliament in 1931. A large area of 31,200 square miles (8,080,762 hectares), its purpose was to provide the Yolngu with, ‘adequate land to meet their hunting and other requirements in order to preserve the aboriginal races’.

A Methodist mission was established at Yirrkala in 1935 but otherwise entry to Arnhem Land was strictly controlled.

Discovery of bauxite in Melville Bay

In 1952 large deposits of bauxite were found by the Australian Aluminium Production Commission in Melville Bay, north of Yirrkala. Bauxite is rock composed mainly of aluminium bearing minerals. Most of the world’s aluminium is extracted from bauxite, so the Arnhem Land deposits were extremely valuable.

After this discovery, legislation controlling access to Aboriginal reserves in the Northern Territory was amended to allow entry for miners and prospectors. The Northern Territory Mining Ordinance 1939–1960 was also amended. This enabled the granting of mining leases and the resumption of land for mining in Aboriginal reserves. The legislation also set out a system of royalties for Aboriginal people, should mining proceed.

From 1953, mining prospectors began appearing around Yirrkala.

Bauxite leases in Arnhem Land

In November 1958 the first bauxite mining lease in Arnhem Land was granted to Comalco. This lease was subsequently cancelled for nonfulfillment of conditions.

In February 1963, Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced the Federal Government had approved plans for the mining and processing of bauxite in north-east Arnhem Land, near Yirrkala.

A total of 140 square miles (36,260 hectares) was removed from the Arnhem Land reserve for bauxite mining leases. Another mining lease was signed with the Gove Bauxite Corporation, a subsidiary of French company Pechiney, the largest producer of aluminium in Europe.

Until this point, the Yolngu were unaware of the development plans or that the government had made it legal for the land to be removed from the reserve for mining.

Australian politicians visit Yirrkala

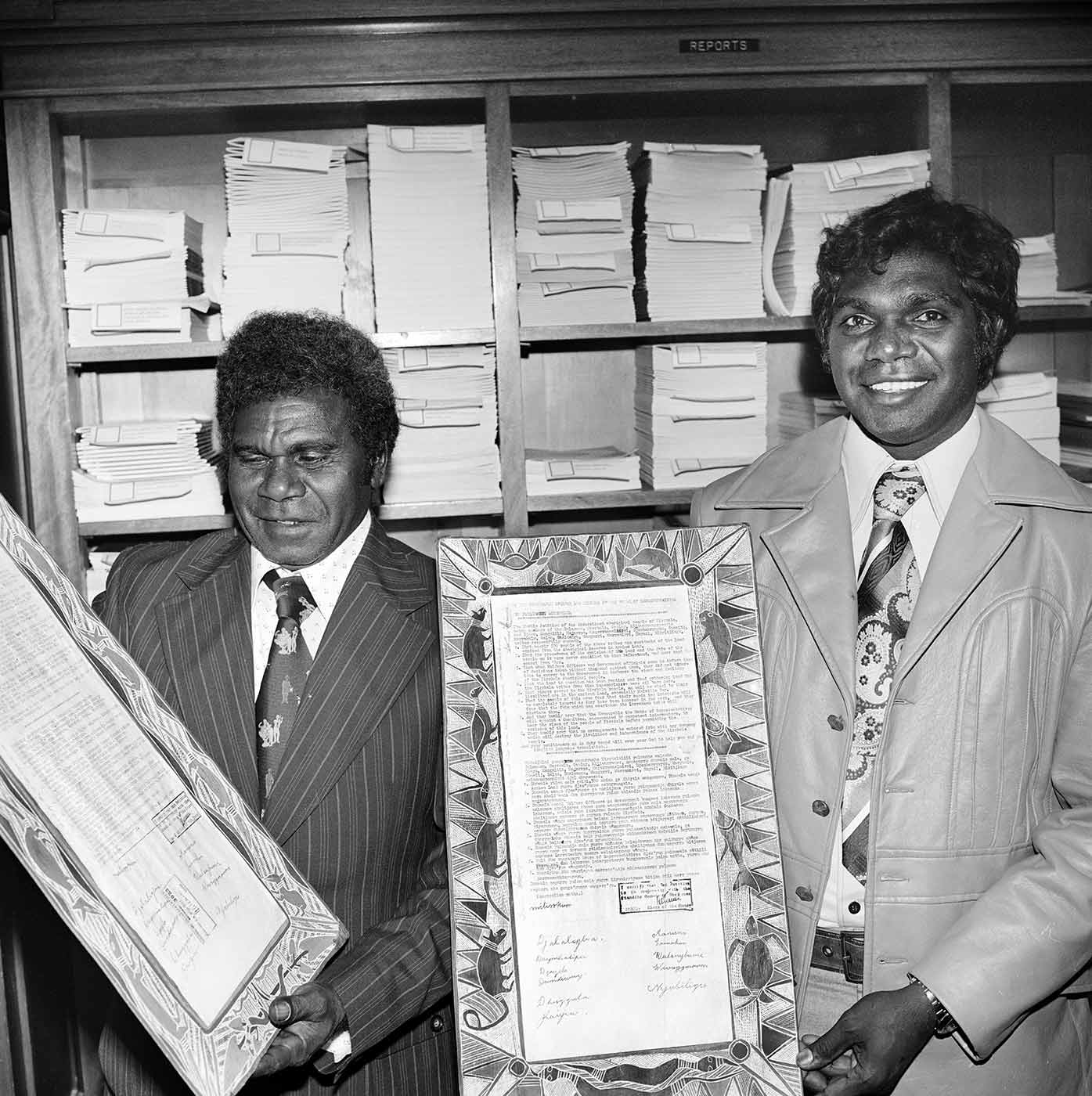

In July 1963 two Labor members of parliament travelled to Arnhem Land – Kim Beazley (senior) and Gordon Bryant, who was also senior vice-president of the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement, later the Federal Council for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advancement.

The trip was in response to lobbying by Yolngu leaders who were angered by the lack of consultation and disregard for their interests by both the Government and mining company Pechiney. They were assisted by the superintendent of the Yirrkala mission, the Reverend Edgar Wells.

The Yolgnu told the parliamentarians they had not been informed about the Federal Government’s plans and showed them mining preparations already underway near Yirrkala and in important fishing areas.

Yirrkala bark petitions

Beazley suggested the Yolngu petition Federal Parliament in a form that expressed their culture. Wells and his wife, Ann, helped to draft the text, which was typed in two languages, English and Gumatj. Eight similar copies of the text were made and four were pasted onto bark.

Senior Yolgnu artists painted clan designs in ochre, charcoal and pipeclay around the edges of the bark. The designs belonged to the two clans whose lands were most threatened by mining activity. The Yolngu artistic system enables the relationship between people and land to be precisely encoded in paintings. For the Yolgnu the inclusion of clan designs on the petition was a demonstration of their ownership of the land.

The petition, signed by nine men and three women, stated that 500 people were residents of the land being removed and the deal had been kept secret from them.

It also declared that sacred sites, such as Melville Bay, were vital to their livelihoods and that the area had been used for hunting and food-gathering since time immemorial.

Tabled in parliament

On 14 August 1963, two petitions, one on bark and one paper, were tabled in the House of Representatives at Parliament House in Canberra.

When the Federal Minister responsible for the Northern Territory tried to dismiss the petitioners as unrepresentative of the Yirrkala clans, the Yolgnu sent another paper petition, signed and thumb-printed by 31 people.

On 28 August 1963, the second bark petition was tabled by Opposition Leader Arthur Calwell.

The other two bark petitions were sent to Gordon Bryant and to Stan Davey, a well-known campaigner for Indigenous rights.

Response to the Yirrkala petitions

The petitions directly led to the establishment of the Select Committee on Grievances of Yirrkala Aborigines, Arnhem Land Reserve. They were the first petitions in Australian history to instigate such an immediate parliamentary response. The committee travelled to Darwin and Yirrkala to hear evidence from the Yolngu and Northern Territory officials.

In October 1963, the committee published a report with its findings. It did not recommend a halt to mining. Instead, it recommended that sacred sites be protected, that compensation for loss of livelihood be paid and that a dedicated committee monitor the mining project.

Nabalco bauxite mine

In 1964 Swiss Aluminium and CSR Limited formed a mining company called Nabalco (North Australian Bauxite and Alumina Company). They began a feasibility study for a bauxite mine near Yirrkala. This was in addition to the project proposed by the Gove Bauxite Corporation.

In 1965 Nabalco received Federal Government approval to develop the bauxite deposit.

Their £50 million project included a mine, processing plan, wharf and a township in the lease area. Under the agreement, royalties would be paid into a trust fund for ‘the general benefit of Territory Aborigines’.

Gove land rights case

In 1968, tired of having their appeals to parliament ignored, the Yolngu decided to launch legal action in the Northern Territory Supreme Court. Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd (also known as the Gove land rights case) is considered the first native title litigation in Australian history.

In 1971, the Yolngu lost the case. Justice Richard Blackburn found any native title held by the Yolngu was not recognised by Australian law and Nabalco was allowed to continue its operations.

While the Yolgnu were unsuccessful in their legal challenge, their actions resulted in the first land rights legislation in Australia, the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. The Arnhem Land Reserve was returned to Traditional Owners, except for the land covered by the Nabalco lease.

Gumatj court action

In 2019, Yolngu leader Galarrwuy Yunupingu lodged a native title compensation claim on behalf of his Gumatj clan. The claim seeks compensation from the Commonwealth Government for the acquisition and destruction of Gumatj land on the Gove Peninsula, acquired for bauxite mining.

The claim argues the Commonwealth was required to compensate the Gumatj on ‘just terms’ when it compulsorily acquired their property. It also challenges the assumption that compensation cannot be sought for acts affecting native title before the start of the Racial Discrimination Act in 1975.

Fourth Yirrkala petition returned

Of the four Yirrkala petitions that were made, two are held at Parliament House in Canberra. The petition sent to Gordon Bryant was donated by his family to the National Museum in 2009.

In 2022 the fourth bark petition was tracked down at the home of Joan McKie, Davey’s former wife, in Derby, Western Australia.

McKie agreed to return the petition to the Yolngu and was present at a handover ceremony in Derby, along with Yolgnu representatives including Yananymul Mununggurr, daughter of Dhunggala Mununggurr, who was the sole surviving petitioner at the time.

The fourth petition was formally returned to the Yolgnu at Yirrkala in December 2023.

In our collection

Museum collection

The Museum's collection also includes a significant collection of Yolgnu bark paintings and several drawings from the 1970s of the Nabalco mine, as seen by students of Yirrkala school.

Other objects from the area include a string bag, handheld fishing net, headband, dancing stick, ceremonial ornament and a spear made by the sons of Gawarrin.

References

Yirrkala bark petitions, Documenting a Democracy

Yirrkala, Collaborating for Indigenous Rights

Report on Yirrkala, Gordon Bryant and Kim Beazley senior, Collaborating for Indigenous Rights

Commonwealth of Australia, House of Representatives, Report of the Select Committee on Grievances of Yirrkala Aborigines, Arnhem Land Reserve 1963, AGPS, Canberra, 1963.

Edgar Wells, Reward and Punishment in Arnhem Land, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra, 1982.

Nancy Williams, The Yolngu and Their Land: A System of Land Tenure and The Fight For Its Recognition, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1986.

Ronald M Berndt and Catherine H Berndt, Arnhem Land: Its History and Its People, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1954.