Almost 400 years ago the Dutch East Indiaman Batavia wrecked near a small group of islands off Australia’s western coast.

What followed remains one of the most bizarre and disturbing incidents in the European history of Australia.

Of the 200 people who survived the wreck, only about 70 would still be alive three months later. Two of these would become Australia’s first, albeit unwilling, European settlers.

Torrentius, heretical Dutch painter and philosopher:

All religions restrict pleasure. In doing so they are contrary to the will of God, who put us on earth that we might, during our brief existence, enjoy without hindrance everything that might give us pleasure.

VOC and the Batavia

The Dutch East India Company, or Vereenigde Oost-indische Compagnie (VOC), was the greatest trade organisation of the age.

Throughout much of the 17th and 18th centuries, it dominated the Indian Ocean spice trade, especially around the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia).

Those with shares in the VOC became immensely rich, while for ambitious young men the voyage to Batavia (now Jakarta) offered an opportunity to make a fortune.

The success and attitude of the VOC reflected the Dutch proverb: ‘Jesus Christ is good, but Trade is better.'

However, the perilous voyage from the Netherlands to Batavia took as long as eight months. Those who survived scurvy and poor food and water then had to face tropical diseases such as malaria once they arrived in the East Indies. The likelihood of dying from such diseases before the end of your first year was one in four.

Launched in 1628, the 150-foot Batavia was the pride of the VOC fleet. Laden with silver, she set sail on her maiden voyage from the Dutch port of Texel on 28 October that year as the flagship of a fleet of eight VOC vessels.

In keeping with VOC practice, the Batavia had two commanders: a senior merchant, or commandeur, who had overall command of the fleet; and a skipper responsible for the ship itself. On the Batavia, these men were Francisco Pelsaert and Ariaen Jacobsz respectively.

Problems inherent in a dual command structure were in this case exacerbated by the fact that Jacobsz and Pelsaert already hated each other due to a dispute in India two years previously.

There were about 330 people aboard the Batavia, among them 180 sailors, about 100 mercenaries, and a number of relatively wealthy passengers, including the 27-year-old Lucretia van den Mylen who was joining her husband in Batavia.

Also on board was Pelsaert’s deputy Jeronimus Cornelisz, a former apothecary who had joined the VOC and signed up for the voyage to avoid being persecuted for his adherence to the heretical values of the painter Torrentius.

Cornelisz befriended Jacobsz and together the two men began plotting a mutiny and recruiting accomplices, presumably tempted by the Batavia’s valuable cargo. Their plans became more feasible when the Batavia separated from the rest of the fleet during a storm off the Cape of Good Hope.

Over the next few weeks they worked on fomenting discontent among the crew. But disaster struck before they could carry out the mutiny.

Wreck of the Batavia

In the small hours of 4 June 1629 the Batavia smashed into Morning Reef just off the Houtman Abrolhos, an island chain 60 kilometres west of what is now Geraldton in Western Australia.

As with all VOC ships at the time, the Batavia had sailed before the prevailing winds known as the Roaring Forties east across the Indian Ocean. Lacking any accurate means of determining longitude, they relied on dead reckoning to decide when to turn north for Batavia. The coast of Western Australia is strewn with wrecks as a result.

When the Batavia hit the reef, discipline collapsed. Sailors traditionally viewed shipwreck as a death sentence. Few could swim and because it was night, no one knew that in this case they were near the relative safety of an island. About 100 people died in the immediate aftermath of the collision.

However, at daybreak the crew used the Batavia’s longboat to get about 180 people and some food and water onto a waterless islet now known as Beacon Island, two kilometres away. The sailors and officers settled on another island nearby. A handful of people remained on the foundering ship.

Ends of the earth

Even today, the Abrolhos islands are very isolated. Four hundred years ago, their remoteness must have seemed lunar.

The Batavia wrecked among the northernmost of the archipelago’s three groups. This, the Wallabi group, comprises a handful of sandy islands spread over an area 17 by 10 kilometres.

Over the next few days Pelsaert and Jacobsz used the longboat to hastily inspect the group’s other islands. Having found neither water nor food, the two men then made the controversial decision to look for water on the Australian mainland or, failing that, get help from Batavia some 3,000 kilometres away.

Pelsaert and Jacobsz left in the middle of the night, taking with them the 40 or so people on their island, mostly sailors along with all the Batavia’s officers.

The Beacon Island survivors woke to find themselves abandoned and alone.

Absolute power

However, not all the VOC officers had left the islands. Cornelisz remained on the Batavia, only abandoning it when the ship sunk under him nine days after it struck the reef.

Staggering ashore on Beacon Island, Cornelisz found 180 desperate, dispirited people looking for a leader.

Cornelisz discovered that an accomplice had revealed his mutiny plot to Pelsaert. It would have been clear to him that any rescue by Pelsaert would mean a death sentence. His only chance lay in taking control of the islands and seizing any rescue ship

Cornelisz began by restoring order and rationing supplies. In recent days, it had rained and some of the Batavia’s food had washed ashore along with canvas the survivors used for tents.

Before his arrival, the survivors had formed a council, which Cornelisz now chaired. He replaced its members with his own men – a coterie of thugs who had been his accomplices in the mutiny plot.

He gathered all the weapons and ensured only he and his men had access to them. He also took control of the makeshift boats and rafts the survivors had made.

Cornelisz then split the population, despatching some to two nearby islands. His main concern was to remove the threat posed by the well-disciplined mercenaries. These he sent to a distant island (now called West Wallabi), ostensibly to find water.

His men ferried the 22 soldiers, under the command of a man called Wiebbe Hayes, the eight kilometres to the island, relieved them of their weapons and left them marooned.

Cornelisz now instigated a drawn-out massacre.

He began by ordering his men to slaughter the entire population of one of the nearby islands. Over the next few weeks, the killing continued on Beacon Island itself. The strongest were killed at night, their throats cut. Others were taken out on rafts and drowned. The sick and lame were also targeted.

Then people were murdered at random, with many forced to kill other survivors to save their own lives. Total obedience was a person’s only chance of survival. Cornelisz’s men raped any woman they chose.

Hayes’s mercenaries

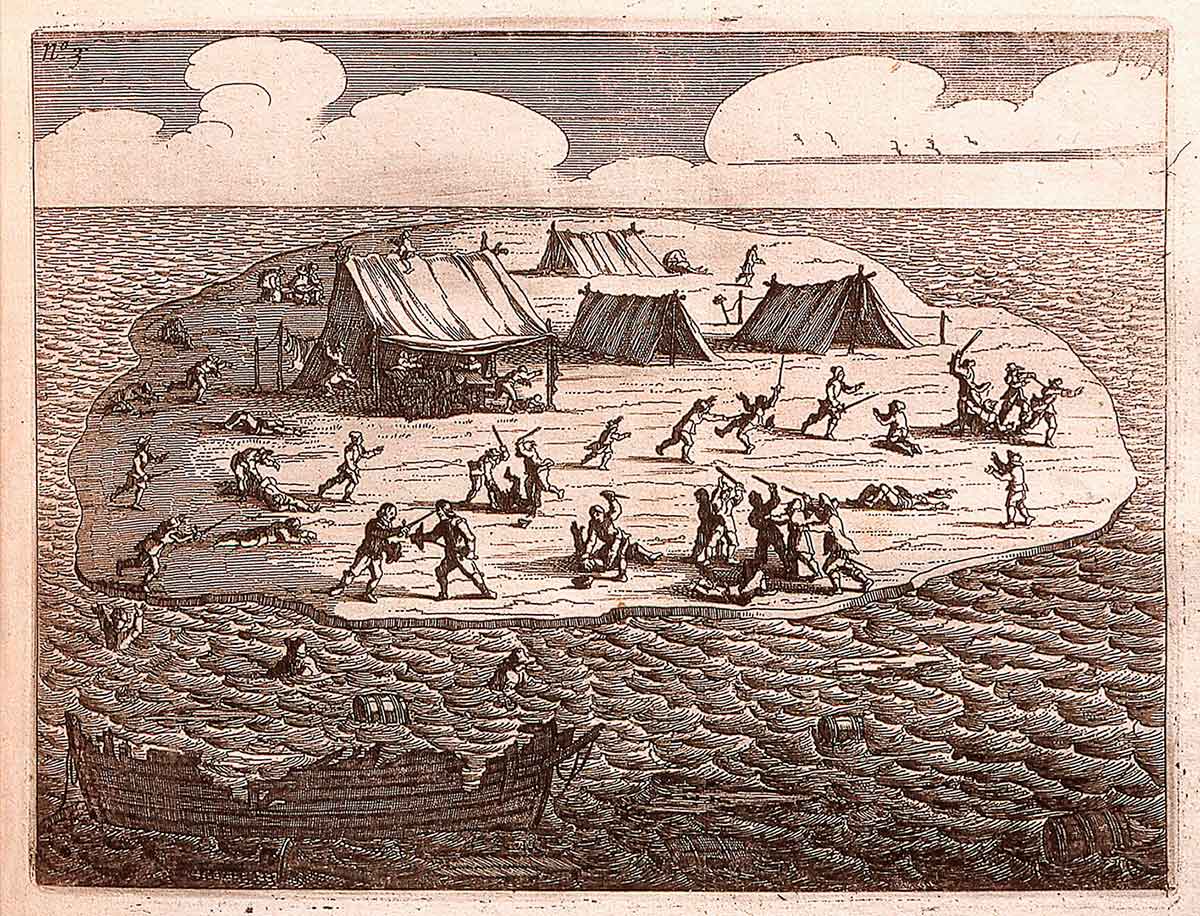

In mid-July Cornelisz ordered the massacre of those on the other nearby island, but several escaped to West Wallabi on makeshift rafts. Forewarned, Hayes then used coral blocks and flotsam to fortify the island and make primitive weapons.

Fortunately for them, and unknown to Cornelisz, Hayes and his men had found not only water on the island but small wallabies, which they were able to kill and eat.

Cornelisz recognised that Hayes and his men were a real threat as they could warn any rescue ship. So in early August he made two attempts to storm West Wallabi. He was repelled on both occasions. On the third attempt, Cornelisz was captured and his three lieutenants killed.

Wouter Looes now took command of the mutineers and on 17 September attacked West Wallabi again. This time he used the mutineers’ two muskets which Cornelisz had been reserving for use against a rescue ship. With these Looes was able to kill three of Hayes’ men. But with the defeat of the mercenaries imminent, a sail was sighted on the horizon.

Fate of the survivors

Pelsaert and Jacobsz had failed to find water or food on the mainland and so had made the long voyage to Batavia. The 33-day journey was a remarkable feat of navigation, particularly as everyone aboard survived.

Once in Batavia, Pelsaert quickly arranged a rescue ship, the Sardam, but it took him seven weeks to make the return voyage to the Abrolhos.

When they saw Pelsaert’s ship both Looes and Hayes each sent a small boat to intercept the Sardam. The first to get there would be able to state their version of events. The fate of the remaining survivors, and those on board the Sardam, depended on the outcome of a rowing race.

Hayes and his men got to Pelsaert first.

Retribution for the mutineers

Pelsaert arrested the men in Looes’s boat and launched a raid on Beacon Island. The mutineers quickly surrendered.

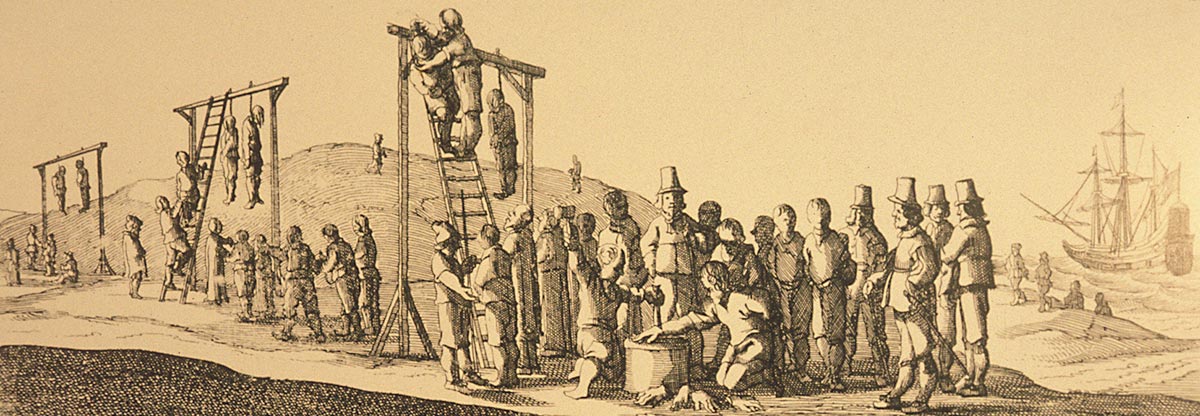

Pelsaert built a jail and tortured the mutineers until they all confessed. Cornelisz and his six closest accomplices were hanged on makeshift gibbets. Pelsaert then spent six weeks salvaging most of the silver from the wreck of the Batavia, before taking the 16 remaining mutineers and 70 survivors to Batavia.

The only mutineers to escape execution were Looes and a cabin boy called Pelgrom, whom Pelsaert decided to maroon on the Australian mainland. Their fate is unknown.

After Batavia

Of the 330 or so people who left the Netherlands on the Batavia, only a third would arrive in the East Indies. Of those who had died, about 125 men, women and children had been murdered by Cornelisz’s men.

The 16 mutineers taken to Batavia were tried, tortured and executed.

For his role in the Abrolhos incident, Hayes was promoted.

Lucretia van den Mylen, who had been forced to become Cornelisz’s concubine, arrived in Batavia to find that her husband had died. She later married an army officer and returned to Amsterdam where she lived to the age of 81.

Having been arrested for negligence soon after arriving in Batavia, Jacobz is believed to have died in jail. Pelsaert died of disease in September 1630, his reputation tarnished by the events off Western Australia.

The wreck of the Batavia was found in 1963. Much of the ship was salvaged and is on display at the Western Australian Maritime Museum in Fremantle.

The remnants of Hayes’s fort – Australia’s first European structure – can still be found on West Wallabi. As many as 80 skeletons are believed to lie in the sands of Beacon Island.

Significance of the wreck of the Batavia

The events on the Abrolhos soon became well-known, at least among the Dutch.

An account of the incident based on Pelsaert’s journals, Ongeluckige Voyagie, published in 1647, was popular enough to warrant eight reprints. It certainly confirmed in the minds of Dutch mariners that the coast of New Holland was utterly unforgiving and should be avoided at all costs.

It is interesting that this bizarre and grotesque bloodbath was among the first events in the history of European contact with Australia – one that is usually overlooked in Australia’s retelling of its history.

It is also noteworthy that Looes and Pelgrom, along with other 17th- and 18th-century shipwreck survivors were, in a sense, the first Europeans to settle in Australia, however unofficial, sporadic and short-lived their presence might have been.

You may also like

References

Batavia's history, Western Australian Museum

Houtman Abrolhos islands, Google Earth

Jeff Sparrow, 'Bring up the bodies', The Monthly

Mike Dash, Batavia’s Graveyard, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2002.

Hugh Edwards, Islands of Angry Ghosts, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1991.

Simon Leys, The Wreck of the Batavia and Prosper, Black Inc, Carlton, 2010.