On 11 November 1975, after a series of dramatic events including a 1974 double dissolution and a budgetary supply crisis, the Gough Whitlam-led federal Labor government became the first (and only) government in Australian history to be dismissed by the Governor-General.

While this constitutional crisis has overshadowed the Whitlam years, the administration left a lasting legacy of social and political reform.

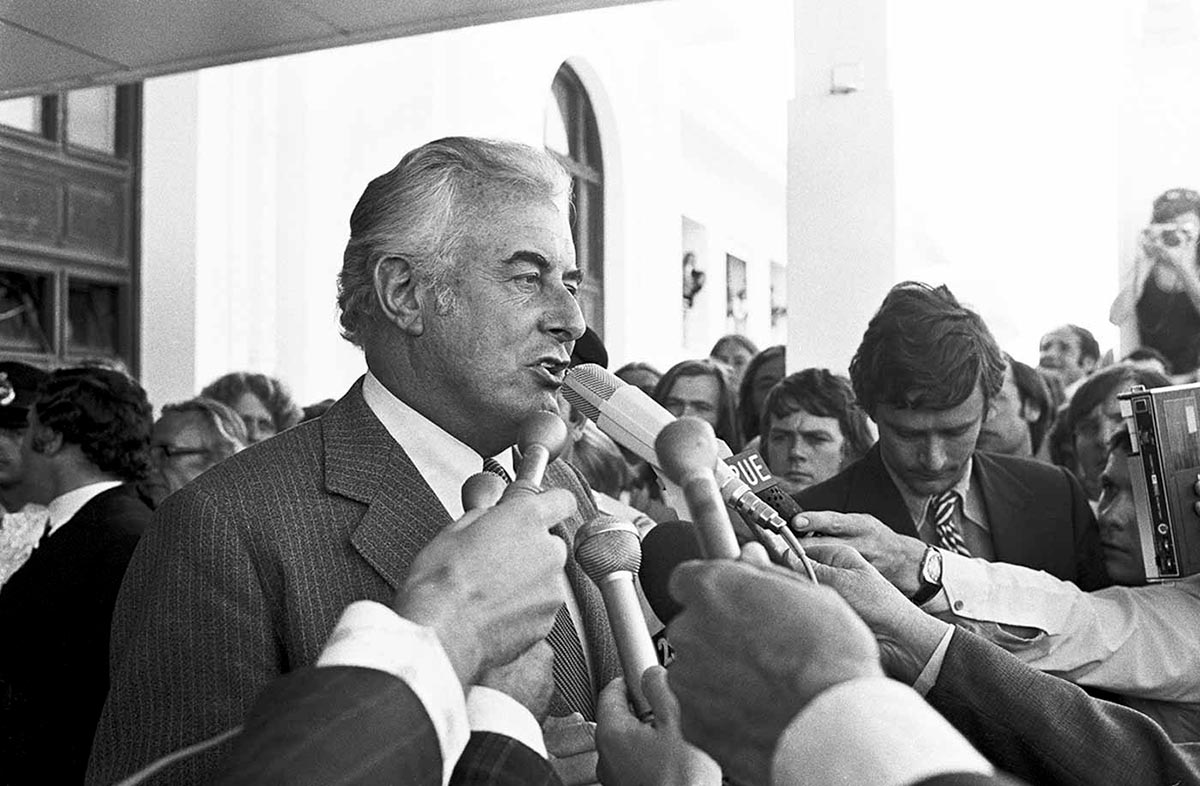

Gough Whitlam, 11 November 1975:

Ladies and gentlemen, well may we say ‘God save the Queen’, because nothing will save the Governor-General.

Election

Under Whitlam’s leadership, the Australian Labor Party (ALP) contested and won the December 1972 election campaign.

After 23 years of Liberal–Country Party Coalition rule, the party’s slogan ‘It’s Time’ reflected the ALP’s hope for a change of government, and for sweeping reforms in the way Australia was governed.

The party campaigned on a platform of significant change. Whitlam’s election campaign priorities included introducing national health care, fostering economic growth and stability, ending Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War and legislating to encourage social justice.

This agenda proved extremely popular, especially with younger Australians.

In the election, the ALP won 49.6 per cent of the primary vote and gained a nine-seat majority in the House of Representatives, making Gough Whitlam Australia’s 21st prime minister.

The Whitlam government

After less than three years in power the Whitlam government had enacted 508 bills.

Significant laws were passed in relation to a range issues, including education, community health and wellbeing, Indigenous Australians, multiculturalism, women’s rights, international relations, defence, environment, economy and the arts.

While the Whitlam government instigated many positive changes, it was not without controversy and opposition. A number of political and economic events culminated in the dismissal of the governing Labor Party on Remembrance Day 1975.

Economy

The Whitlam government came to power as the world economy was slowing. The reduction of oil supply by Arab nations led to soaring energy prices in 1973. This contributed to a worldwide stock market crash between January 1973 and December 1974.

The Australian Senate

Although the government had won a majority in the House of Representatives, it did not dominate the Senate. The ALP immediately began legislating to implement its many election promises, but the Opposition, which controlled the Senate, blocked many of the government bills.

To counteract this, the government offered Vince Gair, leader of the Democratic Labour Party (DLP), the position of ambassador to Ireland. This freed up his Senate seat, which the ALP thought they could win, and thus gain control of the upper house.

Double dissolution

This move so infuriated the DLP (who were unaware of their leader’s negotiations) that it voted with the Coalition against the Labor government’s budget and this led to a double dissolution election set for May 1974.

Labor won the election, but with a reduced majority of seats, and the Coalition missed out on a majority by only a few thousand votes spread over a handful of electorates.

Fraser takes over

Despite the close election, Opposition leader Billy Snedden’s popularity in the Liberal party was waning and in March 1975 Malcolm Fraser mounted a successful leadership challenge.

Meanwhile, Whitlam fired his Minister of Finance, Frank Crean, and replaced him with Jim Cairns, who took a more pro-business outlook.

By-elections and controversies

In June 1975 Lance Barnard, the long-time former Labor deputy prime minister, stepped down from his seat of Bass in northern Tasmania and a by-election was called.

Labor had held the seat for 40 years, but in the by-election the Liberal Party won a stunning victory (Labor’s primary vote having plummeted to just 17 per cent). It was a sign of the changing tide of public opinion.

Around this time, a scandal erupted within the Labor Party over Treasurer Jim Cairns’ hiring of personal secretary Junie Morosi (for whom he later admitted he felt ‘a kind of love’), and in June Whitlam demoted him from treasurer to environment minister.

Loans affair

Cairns had been instrumental in facilitating discussions with a controversial Pakistani loan negotiator, Tirath Khemlani.

A group of senior ministers had been seeking to ensure large loans from Middle East financiers, to allow Rex Connor, the Minister for Minerals and Energy, to implement a series of national development projects, including an upgraded national energy grid and a transnational gas pipeline.

The Opposition questioned the newly demoted Cairns about the issue in parliament, and he denied any knowledge. It was then able to produce signed documents that proved he had been involved. Cairns was removed as minister, and relegated to the back bench.

But then Khemlani came forward with evidence that Rex Connor had gone ahead and kept negotiating the loan deal for a month after he had been told to cease doing so. On October 14 Connor resigned. The ALP was in disarray.

Fraser moves

Malcolm Fraser saw the government was vulnerable and the day after Connor’s resignation the Coalition senators blocked the budget.

Fraser expected Whitlam to call an election, but the government knew now that the public would in all likelihood vote them out of power, so the ALP continued to govern.

The budget was now trapped between an intractable Labor government and a Coalition Opposition that continued to block its passing in the Senate.

The dismissal

On 11 November 1975 Gough Whitlam proposed an immediate ‘half Senate’ election in order to break the stalemate.

This measure was not granted, and in a dramatic and controversial decision Governor-General Sir John Kerr instead dismissed the Whitlam government and appointed Liberal leader Malcolm Fraser as caretaker prime minister.

Fraser immediately arranged for budget supply bills to be passed in the Senate, and called a double dissolution election. On 13 December the Labor Party was soundly defeated at the polls.

Ongoing controversy

The Whitlam government remains the only federal government in Australian history to have been dismissed by the representative of the head of state.

Contention still surrounds the dismissal, which occasioned passionate protest across the nation and divided opinion on both Australian democracy and the functioning of the parliament.

Many opposed the actions of the Governor-General, an officer appointed by the Queen, in sacking a prime minister elected by the Australian people. Many disagreed with the ability of the Senate to block the effective functioning of an elected government.

Others supported the process used to remove Whitlam, to break the parliamentary deadlock and instigate the December 1975 election as a use of constitutional powers, where democratic means had failed to succeed.

In our collection

Explore defining moments

References

Dismissed! Museum of Australian Democracy

Brian Carroll, Whitlam, Rosenberg Publishing, Dural, NSW, 2011.

Jenny Hocking, Gough Whitlam: His Time, (updated ed.), The Miegunyah Press, Carlton, Vic., 2014.

Gough Whitlam, The Truth of the Matter, (3rd ed.), Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2005.