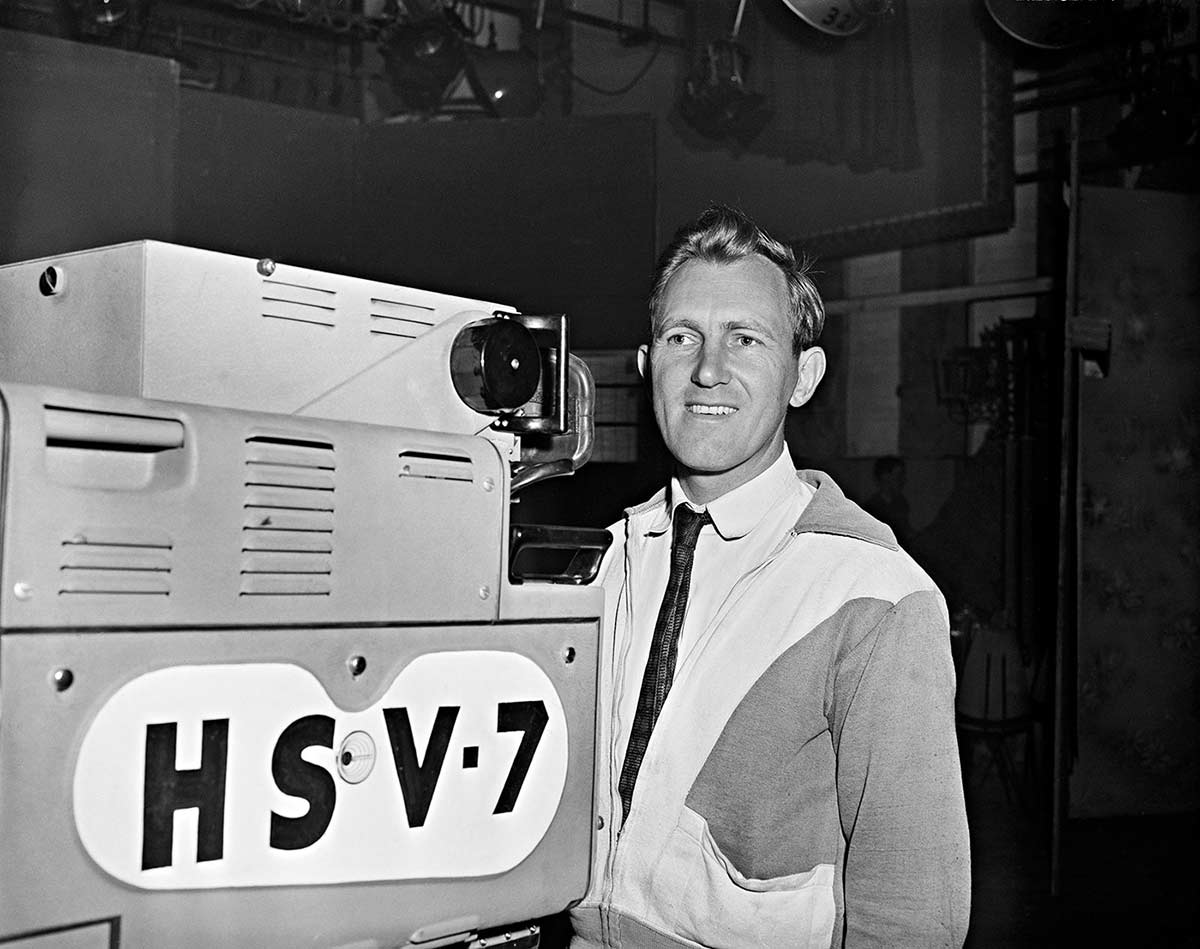

‘Good evening and welcome to television.’ These were the first words spoken on Australian television by Bruce Gyngell on 16 September 1956.

Since that first transmission, television has gone on to become the most influential news and entertainment medium in the nation. From fewer than 100,000 televisions in 1956, there are now more than 18 million operating across Australia.

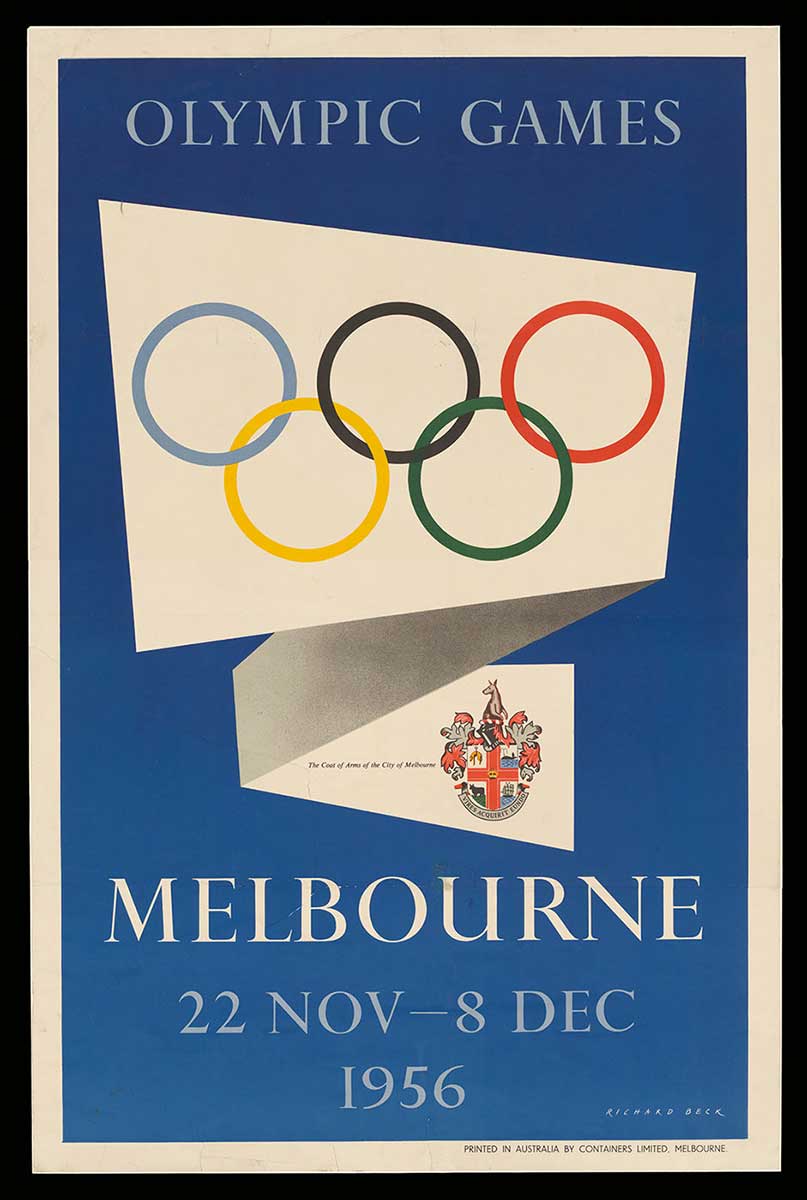

Television broadcasts started just in time for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics – the first games to be held outside Europe or the United States.

Sir Dallas Brooks, Governor of Victoria, 1956:

It is going to be a red letter day not only for Melbourne but all Australia when the Olympic fanfare rings out as the Olympic flag is hoisted in the stadium.

Origins of Australian television

Television experimentation and discussion about its future had begun in Australia in the 1930s but any development was halted by the outbreak of the Second World War.

National debate did not restart until 1949 when Prime Minister Chifley announced that the government would seek to implement a national television service as soon as possible.

However, the Labor government was voted out later that year and the Liberal–Country Party coalition under Prime Minister Robert Menzies came to power.

Menzies was unsure about the impact of television on society. He had said to a visiting representative of the British Broadcasting Corporation in 1952: ‘I hope this thing will not come to Australia in my term of office.'

However, the influence of television around the world was something the Prime Minister could not ignore. The BBC’s first television transmissions had taken place in 1936, programming had started in the United States in 1941, and Canada’s CBC began broadcasting in 1952.

Australians were clamouring for the new technology and Menzies set up a royal commission into television in 1953.

The commission recommended that the Television and Broadcasting Act 1942 be amended to allow for commercial stations to operate, with the goal of establishing a dual system of national and commercial stations along the lines of that developed around radio since the creation of the ABC in 1932.

The government decided that the network should be in place in time for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics.

In 1955, after a series of hearings, the Australian Broadcasting Control Board awarded the first four licences to established firms with substantial investments in radio and publishing, including the major newspaper groups, Packer and Fairfax.

First broadcasts

TCN 9 Sydney produced the first official broadcast on 16 September 1956.

Audiences heard the voice of station announcer John Godson who introduced the station on-air at 7pm, before handing over to Bruce Gyngell.

Formally dressed in a dinner suit, Gyngell appeared on small black and white screens across Sydney and delivered his now famous line, welcoming the nation to television.

Sydneysiders who couldn’t afford a television set crowded into the streets seeking out shop window displays to see the first transmission. Television retailers hosted parties, as did people who had bought a set in advance of the transmission.

HSV7 Melbourne followed suit on 4 November, while the ABC began transmitting from Sydney the following day, just two weeks ahead of the Olympic opening ceremony.

In 1959 television was introduced to Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia, with Tasmania following in 1960 and the Australian Capital Territory in 1962.

Television was so well received that sales of TV sets boomed. The Women’s Weekly offered advice on how to rearrange living rooms to take account of the new addition. Inner-city cinemas and theatres began to close as families preferred to be entertained at home.

Melbourne Olympics

Melbourne was selected to host the Olympic Games on 28 April 1949 at the International Olympic Committee (IOC) session in Rome. Its bid won by a single vote over Buenos Aires, making Melbourne the first city outside Europe or the United States to host the games.

The organisation of the games had a difficult start as disputes over funding between the organising committee and state and federal politicians set back the venues construction schedule. When IOC President Avery Brundage visited the city 18 months before the games opened, he made public his doubts that Melbourne would be ready for the games.

But on 22 November 1956, 103,000 people packed the Melbourne Cricket Ground to watch the opening ceremony parade by teams from 67 nations. Melbourne had pulled it off.

According to the London Evening Standard, ‘Waltzing Matilda danced divinely today. Australia really turned it on. She came of age in the field of sports organisation’.

Australian athletes delivered a stellar performance, the best in Australia’s Olympic history to date. They won 13 gold, 8 silver and 13 bronze medals, and came third on the medal table.

Many of the medal winners, such as Betty Cuthbert, Dawn Fraser and Murray Rose, went on to become household names.

Television

All three stations – TCN 9, HSV 7 and ABN 2 – televised the Olympics, although the precise arrangements for rights to televise particular events were not confirmed until a mere three days beforehand.

The thorny issue of film rights beset the negotiations, with the organisers insisting that rights needed to be paid for, while international film companies and television stations lobbied hard for the Olympics to be classified as news, for which no rights needed to be paid.

Eventually it was agreed that rights would be paid for, and as such Melbourne set an important precedent for all future games.

Multiculturalism and global tensions

The games were described as a ‘gentle exercise in multiculturalism’. It was only 11 years since Arthur Calwell had announced the government’s postwar immigration drive and Australia was still in the early phases of transitioning away from notions of a ‘White Australia’.

Many new migrants turned out to cheer the athletes from their home countries and Australia. The viewing public was presented with visions of people from all nationalities, excelling in their chosen sport and competing in an atmosphere of respect and friendship.

The 1956 Olympics were touted as ‘The Friendly Games’ but they took place against a backdrop of heightened global tensions with the Cold War, the Suez Crisis and the Hungarian Uprising dominating the media.

These hostilities affected the games themselves when Hungary and the Soviet Union became involved in a particularly bloody water polo match.

Olympics closing ceremony

As a result, the organising committee’s chair Kent Hughes took seriously the suggestion of a 17-year-old Chinese–Australian boy, John Ian Wing, to change the format of the closing ceremony.

Wing suggested that athletes march freely as individuals, not as teams representing nations, and that they mingle in the spirit of the ‘Friendly Games’. He said, ‘During the march there will be only one Nation. War, politics and nationality will be forgotten. What more could anyone want, if the whole world could be made as one Nation.'

The organising committee adopted Wing’s suggestion and since then the tradition has been followed at every Olympic Games.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Harry Gordon, Australia and the Olympic Games, University of Queensland Press, 1994.

Bruce Howard, 15 Days in ’56 The First Australian Olympics, Angus & Robertson, NSW, 1995.

Hilary Kent and John Merritt, ‘The Cold War and the Melbourne Olympics’ in Ann Curthoys and John Merritt (eds), Australia’s First Cold War, 1945–1953, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1984.