The release of the oral contraceptive pill ‘Anovlar’ in Australia on 1 February 1961 ushered in a momentous change in women’s lives. Initially available only to married women, and burdened with a 27.5% luxury tax, the pill gave women the freedom to avoid unwanted pregnancies and plan parenthood.

This control over their reproductive future saw more women enter the workforce. Increased participation (and heightened social visibility) became the basis for ongoing social change that included legislation around equal pay for equal work and freedom from discrimination.

In 1972, in his first 10 days in office, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam abolished the luxury tax on all contraceptives, and placed the pill on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme list, reducing its cost to $1 per month.

Margaret Sanger, Woman and the New Race:

No woman can call herself free who does not own and control her own body. No woman can call herself free until she can choose consciously whether or not she will be a mother.

Women and contraception

The arrival of the oral contraception pill in Australia in 1961 took place against a range of issues.

These included the global population explosion, ever-present fears of ‘racial decline’, longstanding moral strictures about women’s sexuality and fertility, the emergence of the second wave of the women’s liberation movement and concerns about potential physical side effects highlighted by the thalidomide tragedy.

The pill was part of, and contributed to, many social changes that improved the status of women in the second half of the 20th century. The women’s movement sought better health care for women, including the right to control their fertility, better childcare, equal pay for equal work, and freedom from sexual violence.

From the 5th century onwards, the Roman Catholic Church has taken a strong stance against the use of contraception – an opposition that continues into the 21st century – but demographic studies of European birth rates reveal widespread limitation of human fertility over many centuries.

Ever since Richard Carlile published Every woman’s book, or, What is love?: containing most important instructions for the prudent regulation of the principle of love, and the number of a family in 1828, information about contraception has been published despite prosecutions for obscenity.

Marie Stopes and Margaret Sanger are the two most famous advocates of birth control of the early 20th century, and did much to bring the subject into open public debate.

Significance of the pill

Sanger encouraged Gregory Pincus and John Rock, the creators of the pill, to undertake research in the face of the medical establishment’s reluctance to fund research into fertility control.

Sanger also persuaded private philanthropist and feminist Katherine McCormick to fund Rock’s research.

Trials started in 1954, and the first oral contraceptive pill (Enovid) was approved by the US Food and Drugs Administration on 9 May 1960. It was released in Australia on 1 February 1961 under the name Anovlar.

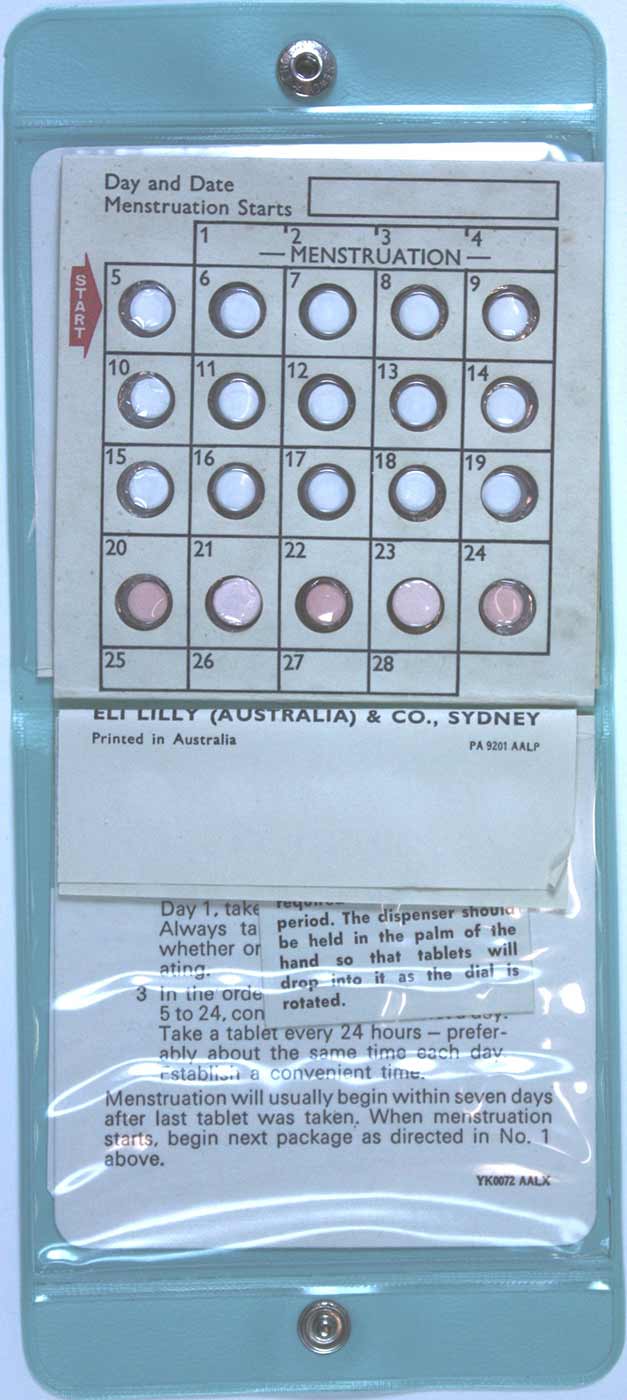

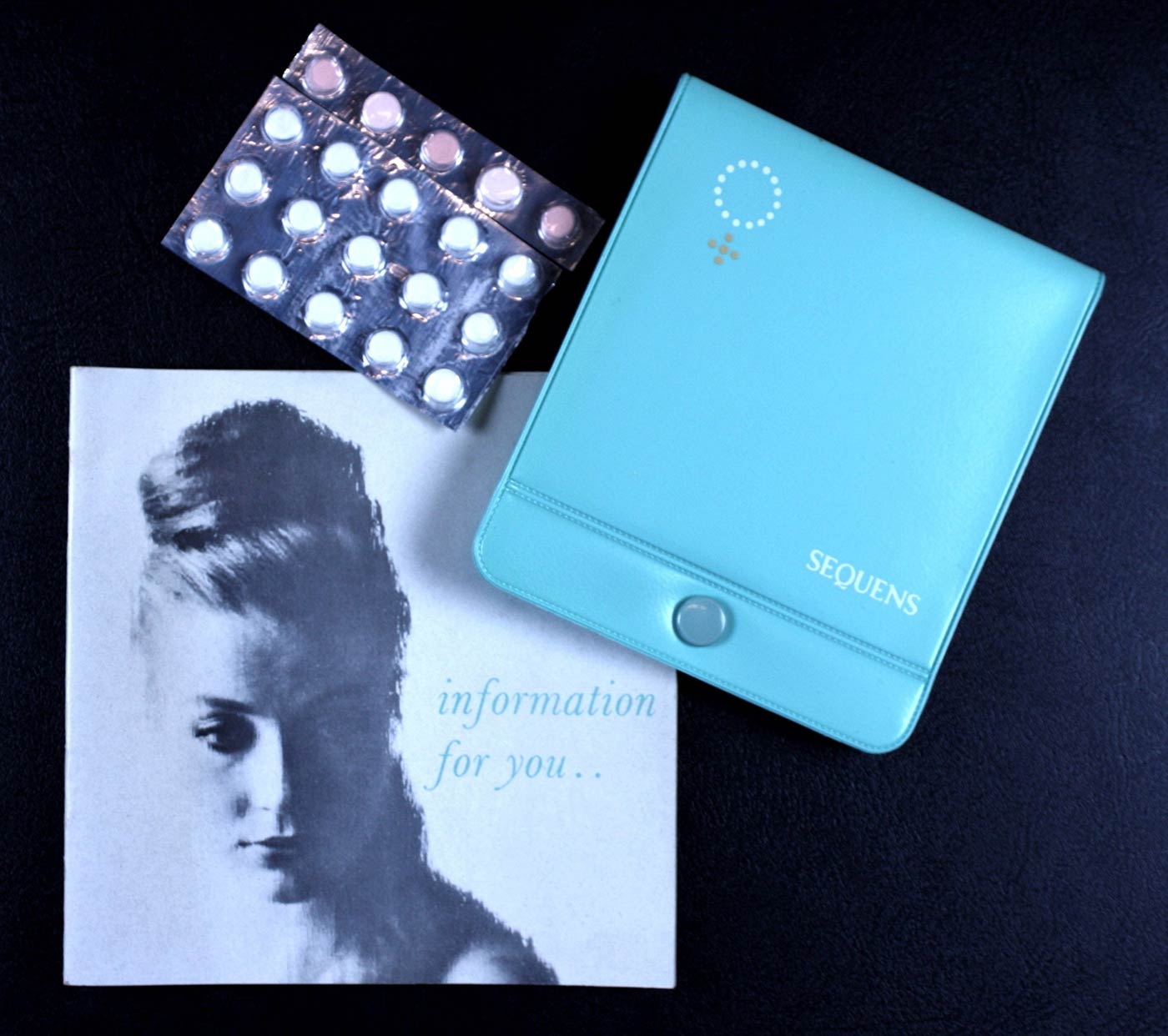

What was so radical about the oral contraceptive pill was the freedom and simplicity it offered women. Whereas previous forms of contraception were messy, unreliable, and even passion killing, the pill was simple to use, easy to hide, and markedly more effective. It worked by adjusting levels of hormones in a woman’s body, preventing ovulation.

Early formulations of the pill had high levels of synthetic oestrogen, which often produced side effects such as nausea or weight gain. Later versions of the pill decreased the levels of hormones released into the body, and side effects correspondingly decreased.

The pill remains among the most popular and safest forms of birth control, although some religious groups remain opposed to the use of all forms of artificial contraception. Despite concerted lobbying by John Rock, the Catholic Church renewed its stance against contraception in 1968.

Initially, the pill was only available to married women with a prescription, reflecting longstanding social mores that sex was only appropriate within marriage.

However, statistics show that the incidence of sexual activity outside of marriage had been on the rise from 1945, along with a rise in out-of-wedlock pregnancies until the early 1970s.

This was probably the result of less stringent supervision of young people, the greater access of young people to cars, and the refusal of doctors to supply the pill to single women.

Conversely, the pill also contributed to a drop in fertility within marriage as many newly-weds took advantage of the opportunity to delay starting a family.

When the German drug manufacturer Schering released ‘Anovlar’ in Australia, legislation prevented the company from advertising the pill.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

‘Oral contraceptive pill made available in Australia’, ABC

Lesley A Hall, ‘Contraception’, in JL Heilbron (ed), The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science, 2003, pp 178–9.

Lara V Marks, Sexual Chemistry: A History of the Contraceptive Pill, Yale University Press, 2001.

Margaret Marsh and Wanda Ronner, The Fertility Doctor: John Rock and the Reproductive Revolution, Johns Hopkins University Press, Maryland, 2008.

Elizabeth Siegel Watkins, On the Pill: A Social History of Oral Contraceptives, 1950–1970, John Hopkins University Press, Maryland, 1998.

‘Non-marital pregnancy and the second demographic transition in Australia in historical perspective’, Gordon Carmichael in Demographic Research, vol. 30, article 21, pp 609–40, 5 March 2014.