From the first recorded contact between Europeans and Tasmania’s Aboriginal population in 1772, relations between the two peoples were hostile.

By 1830 a virtual state of war existed and many settlers were demanding that something decisive be done.

In response, Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur ordered thousands of able-bodied settlers to form what became known as the ‘Black Line’, a human chain that crossed the settled districts of Tasmania.

The line moved south over many weeks in an attempt to intimidate, capture, displace and relocate the remaining Aboriginal people.

The plan failed in the short-term but it ultimately allowed Europeans to take control of the region.

Lieutenant-Governor of Tasmania, George Arthur, September 1830:

The community being called upon to act en masse on the 7th October next, for the purpose of capturing those hostile tribes of the natives which are daily committing renewed atrocities upon the settlers … Active operations will at first be chiefly directed against the tribes which occupy the country south of a line drawn from Waterloo Point east, to Lake Echo west …

First Tasmanians

Until about 12,000 years ago low sea levels meant that Tasmania was joined to the Australian mainland by a land bridge. The original Tasmanians settled the area by migrating from mainland Australia across this bridge an estimated 40,000 years ago.

When sea levels rose due to the vast melt that followed the end of the last ice age, the land bridge flooded to form Bass Strait. Tasmanians, on the island they called Trowunna, developed in isolation from other mainland Australian Aboriginal nations.

The environment was resource rich, providing excellent hunting grounds and fresh water sources for the Tasmanian Aborigines. Prior to European colonisation, there were up to 15,000 Aboriginal people living in nine nations.

European settlement

While Abel Tasman was the first European to map parts of Tasmania, naming it Van Diemen’s Land in 1642, the first documented contact between Tasmanian Aborigines and Europeans occurred in 1772.

French sailors, led by Marc-Joseph Marion Dufresne, came ashore on the east coast of the island and encountered members of a coastal tribe. This first contact quickly became hostile, and at least one Aboriginal Tasmanian was killed.

Whaling and sealing were the first European industries in Australia after British colonists and convicts began arriving from 1788. The movement of ships through the Southern Ocean led to further contact between Tasmanian Aborigines and Europeans, especially on small islands off the coast.

These Europeans were responsible for introducing diseases into the Tasmanian community, as well as abducting women and children from coastal tribes to be used as ‘wives’ and labour on ships. This devastated the Aboriginal population.

The first permanent European settlement in Tasmania was at Risdon Cove in 1803. The British established the settlement not only to expand their Australian colony but because they were concerned that the French, with whom they were at war, might try to claim the island.

The British population in Tasmania consisted mainly of military personnel and convicts, and a small number of free settlers. The initial population numbered fewer than 3,000. However, by 1830 it had increased to about 23,500.

Aboriginal resistance

A rapidly growing British population in Tasmania and the ongoing destruction of Aboriginal tribes by disease, dispossession and violence led to intense conflict between the two groups. Tasmanian Aborigines were vehemently opposed to British expansion and its impact on their home and communities.

By the mid-1820s the situation had become desperate for Aboriginal people, whose numbers had fallen to fewer than 2,000 by about 1818.

Nearly one million sheep had been moved into prime grazing land that was also the native habitat of Aboriginal food sources like kangaroos and other native animals. The sheep destroyed local ecosystems and disrupted food and water sources.

In about 1824 the ‘Black War’ began. The most extensive conflict in Australian history, the Black War was extremely violent. Settlers drove Tasmanian Aborigines from their lands, murdering many. Tasmanian Aborigines also attacked and killed settlers and their families, raiding houses and farms for food and resources, and trying to drive out the British.

Most of the frontier conflict was concentrated on the traditional lands of four nations – the Oyster Bay, Big River, North Midlands and Ben Lomond peoples. The land in this region was extremely productive and was quickly occupied by European settlers.

Some of the most famous Aboriginal resistance leaders from these nations were Tongerlongter, Montpeliater, Mannalargenna, Umarrah and Wareternatterlargener.

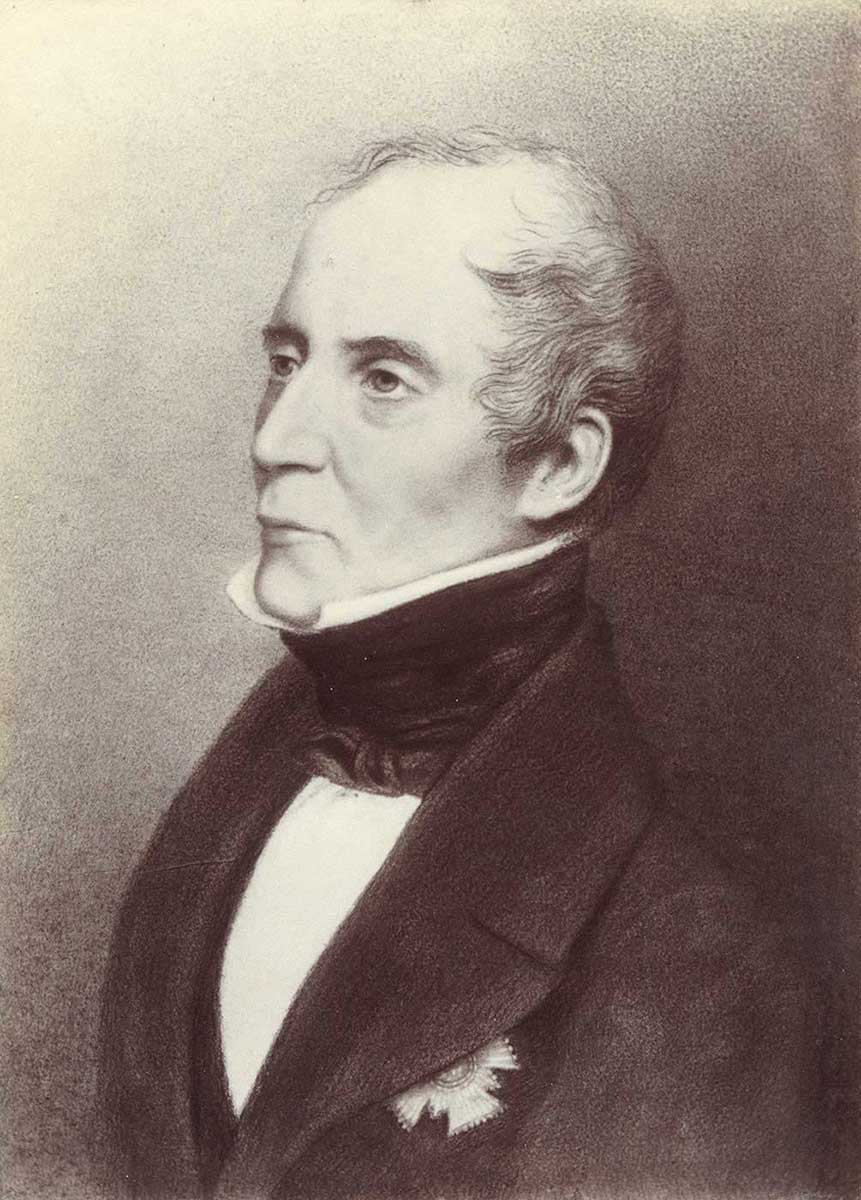

George Arthur

Colonel George Arthur took up office as Lieutenant Governor of Tasmania in 1824, just as hostilities with Tasmanian Aborigines began to have a significant impact on the British population of the island.

Initially, Arthur dealt with Tasmanian Aborigine resistance-fighters by treating them as criminals and bringing them before the courts for punishment when they were caught.

By 1826 this approach was proving fruitless, and Arthur declared all Aboriginal resistance-fighters to be insurgents, meaning that soldiers and police could raid Aboriginal camps without provocation to arrest and detain any Tasmanian Aborigines they found.

Many Tasmanian Aborigines were shot on sight, including women and children, leading to further escalations in retaliatory violence.

In 1828 the fighting had become so vicious that Arthur declared martial law in the settled districts, labelling Tasmanian Aborigines as ‘open enemies’ of the state and giving them no protection under the law.

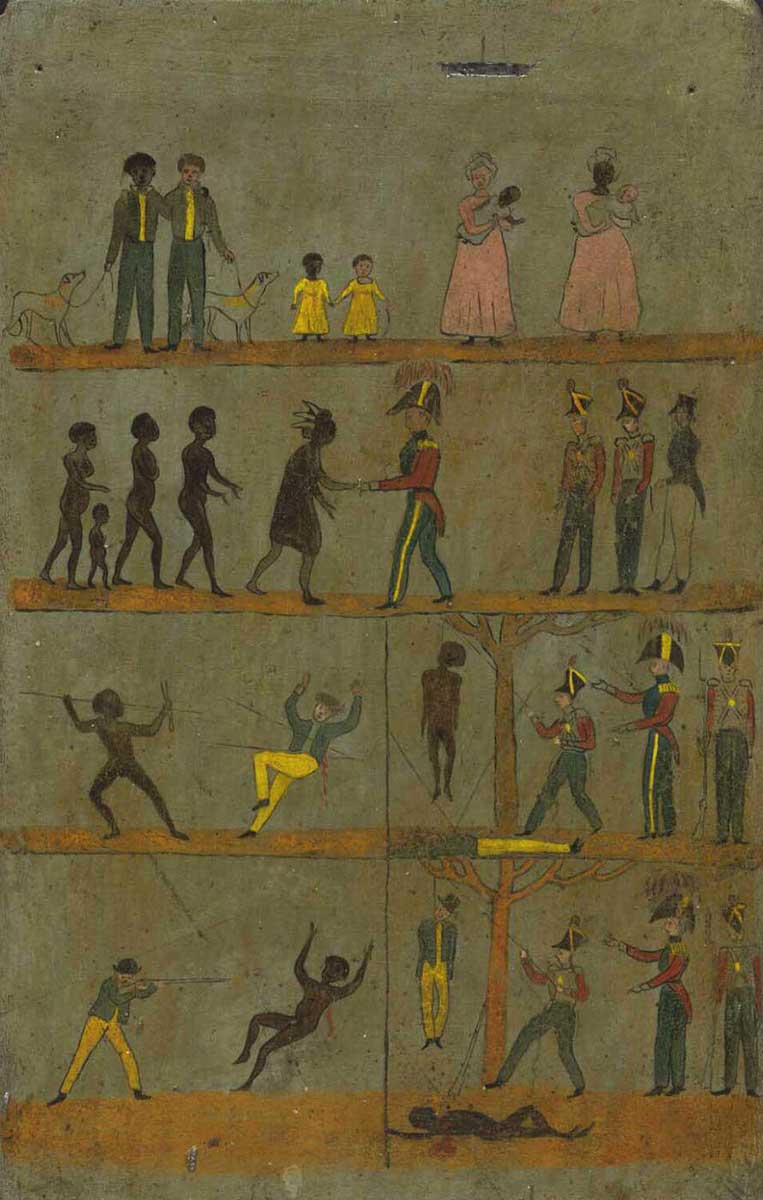

In 1830 Arthur issued his now famous proclamation (pictured below), implying equality under the law for both black and white citizens, in an attempt to calm the escalating situation. This equality was, however, non-existent, with white people seldom properly punished for the same crimes for which Tasmanian Aborigines were hanged.

By 1830 all attempts to quell the violence were failing. Arthur was openly criticised by settlers who felt he wasn’t doing enough to protect them and their assets, and the issue was often discussed with passion in the colony’s press.

In September 1830 under pressure from the advisory Aborigines Committee, made up of private citizens who threatened to take matters even further into their own hands, Arthur called for a leveé en masse (a large conscripted force of able-bodied men).

Black Line

The leveé, soon called the ‘Black Line’, was designed to force the Oyster Bay, Big River, North Midlands and Ben Lomond nations from their lands.

Colonists would form a line stretching across the settled districts and move south, pushing the local Tasmanian Aborigines onto the Tasman Peninsula where they could be rounded up.

From there they would be relocated to Tasmania’s offshore islands, putting an end to their resistance.

The authorities had estimated that the number of Tasmanian Aborigines in these settled districts might be in the low thousands, based on the damage to European settlements they had done.

The reality was that most of the population had died or moved to other districts, and it is likely that fewer than 300 remained.

The Tasmanian Aborigines who were still on their traditional lands were very organised and used guerrilla warfare tactics to inflict high levels of damage despite their low numbers.

On 7 October 1830 more than 2,200 settlers, military, police and convicts, reported to seven prearranged locations across the settled districts. The largest force ever mobilised against Aboriginal people anywhere in Australia, the line represented about ten per cent of the European Tasmanian population.

The costs associated with this operation were huge, amounting to more than £30,000, about half of the revenue collected in the colony that year.

Over a number of weeks, three separate lines of men moved slowly across the Tasmanian landscape. While there were sightings of Tasmanian Aborigines, the line did not have much success in forcing them to the south, with most slipping back into their traditional lands.

Only two Tasmanian Aborigines were documented as captured, and the same number recorded as killed during the operation.

Relocation and destruction

While the Black Line was considered a logistical failure, in the long term it did have the effect desired by government authorities and settlers.

The scale of the operation, along with ongoing violence and disruption from Europeans, troubled the Tasmanian Aborigines and they began to avoid living in the settled districts. Most were eventually persuaded to surrender to the authorities.

George Augustus Robinson, an Englishman whom Governor Arthur had appointed as conciliator to the Aboriginals in 1829, often negotiated this surrender.

Robinson learned some of the local Aboriginal languages, and attempted to form cordial relationships with people in the settled districts. He frequently travelled with other Aboriginal Tasmanians, like Truganini, using them as intermediaries and representatives who could convince groups to relocate.

The small population of about 200 Tasmanian Aborigines who remained in the settled districts after the line were gradually removed to Wybalenna, a settlement on Flinders Island in Bass Strait run by Robinson.

Confined to poor accommodation, exiled from their homes, suffering emotional trauma, plagued by disease and severely malnourished, most of those at the settlement died within a few years.

By 1847 only 40 people still survived at Wybalenna. Considered the ‘last remaining’ Tasmanian Aborigines, this small group was relocated to the Tasmanian mainland at Oyster Cove. By 1876 all but one of them had passed away.

Tasmanian Aborigines people today

Despite the savage reduction in their numbers and widespread attempts by settlers to remove all Tasmanian Aborigines from the colony of Tasmania, the Tasmanian Aborigine in the state today is thriving. According to the 2016 census 23,580 people in Tasmania identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.

Culture and traditions, passed down by the Aboriginal survivors of early European violence, are alive and well. Traditional skills such as basket and necklace making and mutton birding are prominent in the community, who also participate in ceremony and learning and sharing language with younger generations.

References

Black War, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Proclamation cup, reCollections magazine

'The Black Line in Van Diemen’s Land’ by Lyndall Ryan, Journal of Australian Studies

John Connor, ‘British frontier warfare logistics and the “Black Line”, Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), 1830’, War In History, 2002, vol. 9, no. 2, pp 143–158.

Henry Melville, The History of Van Diemen’s Land From the Year 1824 to 1835, Inclusive, During the Administration of Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur, Australian Historical Monographs, vols 25–27, Sydney, 1959.

Lyndall Ryan, Tasmania Aborigines: A History Since 1803, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2012.