On 24 October 1889 Henry Parkes delivered a speech at the Tenterfield School of Arts on the need for the Australian colonies to federate into one nation.

The Tenterfield Oration is significant because, although politicians had been discussing federation for some time, this was the first direct appeal to the public.

Sir Henry Parkes, Tenterfield, 24 October 1889:

The great question which we have to consider is, whether the time has not now arisen for the creation on this Australian continent of an Australian government and an Australian parliament … Surely what the Americans have done by war, Australians can bring about in peace.

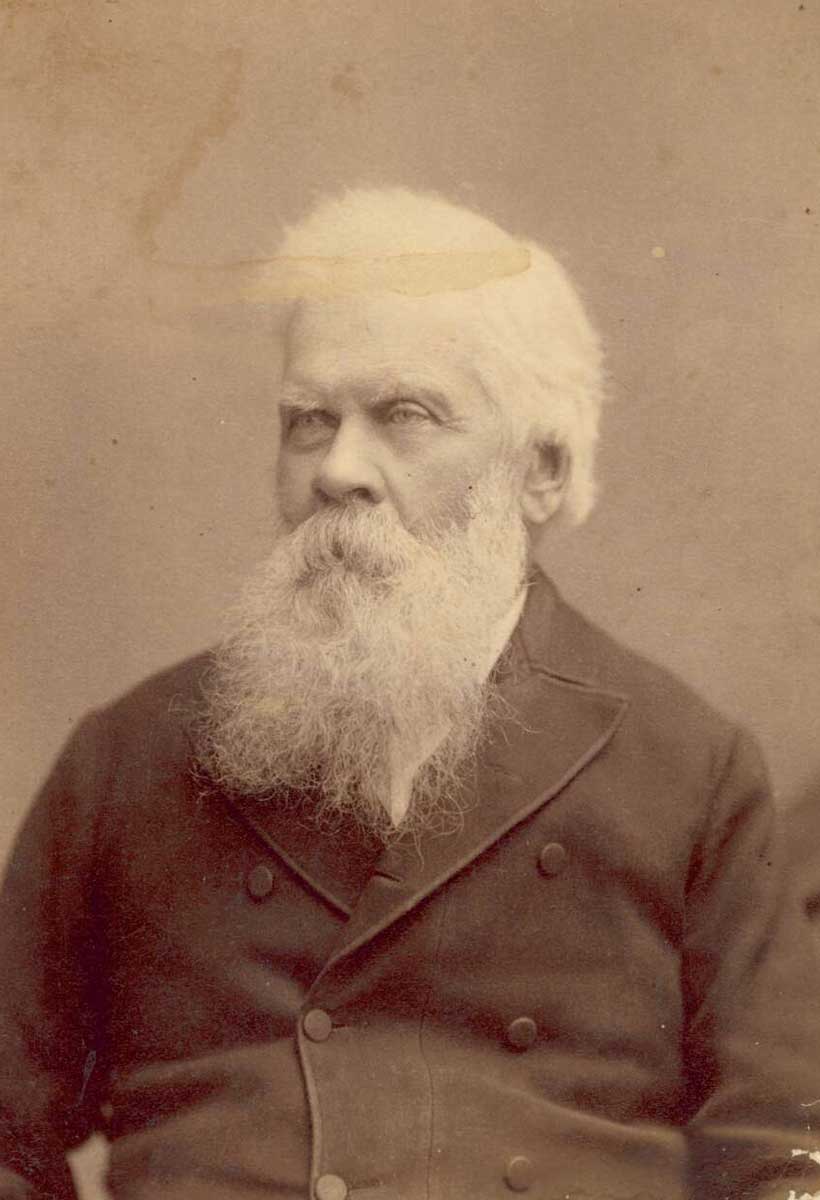

Henry Parkes

Henry Parkes and his young family arrived in Sydney from England as impoverished immigrants in 1839. Almost immediately Parkes became active in politics and in 1856 gained a seat in the first New South Wales Legislative Assembly.

Parkes eventually served five terms as Premier of New South Wales. He was a master of the factional politics that dominated colonial governments before the cementing of party lines in the early 20th century.

From early in his political career, Parkes was a supporter of federation. He joined the radical Constitution Association in 1848, and in 1850 established the Empire newspaper, which became the voice of republican and federal thinkers.

In 1867 at an inter-colonial conference in Melbourne, Parkes said, ‘I think the time has arrived when these colonies should be united by some federal bond of connection.’

Ideas of federation

The Australian colonies had developed separately for the first hundred years of their existence but by the 1880s a move towards economic and social integration had started. The tariffs levied on goods moving across borders began to be seen as burdensome and a sense of Australian nationalism was growing.

The New South Wales Government under Parkes had passed the Influx of Chinese Restriction Act in 1881, a Bill limiting Chinese entry to the colony. This led to an inter-colonial conference to discuss a coordinated approach to Asian immigration that same year.

At the conference, Parkes formally proposed a federal council to begin discussion on unification of the colonies. The colony of Victoria, however, refused to join.

In 1883 France and Germany established colonies north of the continent in the New Hebrides and New Guinea respectively and the Australian colonies met in Sydney to consider a coherent defence plan. Victoria proposed a formal union, but New South Wales was against any amalgamation if Victoria was leading the movement.

A token Federal Council was established but New South Wales and South Australia refused to join so it had limited power to implement any change.

Perhaps the greatest stumbling block in the way of federation was the ideological division between the two most populous colonies. Victoria was committed to trade protectionism and advocated protective tariffs, believing they would allow industry to grow and provide employment. In opposition to this, New South Wales steadfastly supported free trade.

Parkes and Carrington

By 1888, 70 per cent of Australia’s inhabitants had been born on the continent. Across the British Empire there was growing enthusiasm for federation within self-governing colonies.

Canada had become a dominion in 1867 and England saw the future of other British colonies such as Australia, New Zealand and South Africa in similar terms.

Defence of its colonies was becoming an economic and diplomatic issue for Britain. Between July and October 1889, General Sir James Bevan Edwards toured Australia and reported on its defences.

He noted that the colonial military lacked organisation, training and equipment and that, ‘forces should at once be placed on a proper footing; but this is, however, quite impossible without a federation of the forces of the different colonies’.

On 15 June 1889 Parkes had a long conversation with New South Wales Governor Lord Carrington who was an advocate of federation. During the discussion Parkes boasted he could federate the colonies in 12 months and Carrington, pandering to the politician’s well-known vanity, dared him to do so.

Parkes decided to put all his efforts into the movement. On 15 October 1889 he telegraphed the premiers of the other colonies suggesting a conference to discuss a new constitution and soon after travelled to Brisbane to consider the situation with his Queensland colleagues.

Tenterfield

On his return from Brisbane, Parkes stopped in Tenterfield, northern New South Wales. Tenterfield had a special place in Parkes’s life because in the colonial election of 1882 he had lost his East Sydney seat and the next day was allowed to run for the Tenterfield seat where the local population returned him to parliament.

For Tenterfield, the unfederated nature of the colonies was of particular concern. Its position close to the Queensland border meant that much of its trade was inhibited by high tariffs.

Discussions around colonial defence also affected Tenterfield because it was rural towns that contributed the men and equipment to the new light horse military units the colony was raising.

Tenterfield Oration

In the Oration, Parkes argued that federation would enable the colonies’ militias to unite as a single national army under the command of a single national government. He also argued that it would enable Australia’s railway gauges to be of a uniform width.

As a first step towards federation he recommended that a convention be held comprising delegates from each of the colonies to draw up a constitution.

He concluded with:

I believe that the time has come, and if two Governments set an example, the others must soon of necessity follow …

The opportunity has arisen for the consideration of this great subject and I believe that the time is at hand … when this thing will be done.

Indeed, this great thing will have to be done, and to put it off will only tend to make the difficulties which stand in the way, greater.

Federation

The Tenterfield Oration is significant because it is seen as the first direct appeal to the public rather than to a political audience for federation.

Parkes spent the night in Tenterfield and the speech was reported in the Sydney newspapers. Lord Carrington telegraphed him to immediately return to Sydney to deliver the same speech there as soon as possible.

Parkes did so and then presented similar addresses 15 times in different locations over the next nine months.

Australia became a federated nation on 1 January 1901.

In our collection

You may also like

References

Sir Henry Parkes at Tenterfield, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 October 1889, Trove

Sir Henry Parkes' Tenterfield Oration educational resource, ABC Radio National

David Headon and John Williams, Makers of Miracles: The Cast of the Federation Story, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 2000.

Helen Irving, The Centenary Companion to Australian Federation, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2000.

Mark McKenna, The Captive Republic: A History of Republicanism in Australia, 1788–1996, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1996.