On 19 March 1932 the Sydney Harbour Bridge opened to the public. The event marked the end of almost a century of speculation and planning around a bridge or tunnel that would cross the harbour.

In 1922 the New South Wales Parliament passed the Sydney Harbour Bridge Act and preparation for the building got underway.

Construction began on the approaches to the span in 1923 and on the bridge itself in 1925. More than 1,600 people worked on the bridge during its construction.

In 2017 more than 200 trains, 160,000 vehicles and 1,900 bikes used the bridge every day.

HE Horne, 'Song for the Bridge', February 1932:

Behold the Arch of Wonder

With sunset all aglow

When sea and sky bring heaven nigh

And tides eternal flow;

O bridge of Light to greater height

Thy call shall ever be

Where beauty dwells and casts her spells

In Sydney by the sea.

Early bridge proposals

A desire to span the harbour goes back to the early days of the penal settlement at Sydney.

Francis Greenway proposed a bridge to Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1815. Greenway, convicted of forgery in 1812 and sentenced to 14 years transportation to New South Wales had previously practised as an architect, a skill much in demand in the colony.

With a letter of recommendation from former Governor Arthur Phillip he was swiftly able to gain a ticket of leave and enjoy the patronage of Governor Macquarie. In 1816 Macquarie appointed him civil architect.

The idea took different forms throughout the 19th century but engineer Peter R Henderson’s 1857 design of a bridge from Dawes Point to Milson’s Point is considered the first serious proposal.

Construction and opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge film. Footage supplied by the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia’s Film Australia Collection.

William C Bennett, the Sydney Commissioner for Roads and Bridges estimated in 1878 that a harbour bridge would cost £1.2 million – a prohibitive sum for the young colony.

In 1890 the Royal Commission on City and Suburban Railways was convened. It investigated the possibility of a bridge but concluded, ‘it is inexpedient at present to connect the North Shore with Sydney by means of a bridge or tunnel’.

In January 1900 as part of a wide-ranging overhaul of the Sydney rail system, which also included the redevelopment of Sydney’s Central Station, the NSW Government put out a call for designs and tenders for a harbour bridge.

In 1903 a plan by Sydney engineering firm Stewart & Co was accepted as the ‘most satisfactory design’, but with an estimated cost of almost £2,000,000, the construction was again put on hold.

Chief engineer John Bradfield

In 1912 John Job Crew Bradfield was appointed chief engineer, Sydney Harbour Bridge and City Transit.

Bradfield became the project’s greatest advocate and is remembered as the ‘father’ of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. However, the First World War put a halt to all plans for a bridge.

Finally, in November 1922 the Sydney Harbour Bridge Act was passed by the New South Wales Parliament.

Bradfield could now begin planning for the bridge in earnest and in January 1923 he issued calls for tender for the ‘Construction of a Cantilever or an Arch Bridge across Sydney Harbour’.

International competition

The international competition closed on 16 January 1924. Six firms from around the world had submitted 20 proposals.

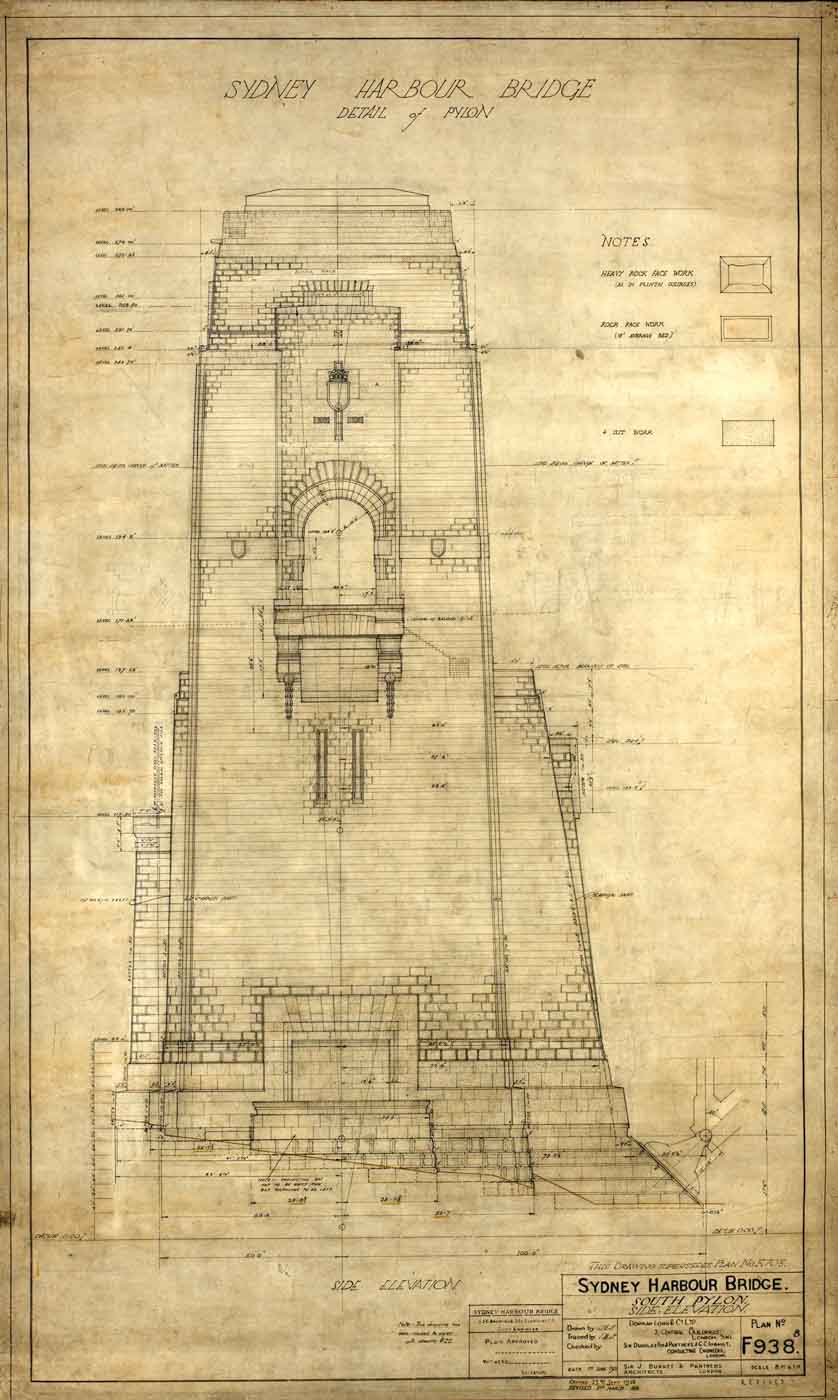

Bradfield and his team put together their Report on Tenders and recommended design A3 – a two-hinged steel arch with abutment towers designed by Dorman, Long & Co of Middlesbrough, England.

Bradfield was impressed by the company’s track record, the 'dignity’ of the design and the fact that Dorman Long was the only tenderer to stipulate that all fabrication would take place in Australia.

Dorman Long’s consulting engineer, Ralph Freeman of Sir Douglas Fox and Partners, oversaw the detail of the bridge design. The aesthetics of the span, especially the striking granite-faced tower pylons, were handled by consulting architects Sir John Burnet and Partners.

Housing demolition

The government had to clear hundreds of houses from the northern and southern approaches to the bridge. This was a painful process for residents as their homes, and in some instances their businesses, were ‘resumed’ by the state government, sometimes without compensation.

Many homes in the area between the Rocks and Darling Harbour had already been bought by the government during the outbreak of bubonic plague of 1900.

A total of 802 buildings were demolished.

Construction

The first sod was turned for the building of the bridge in July 1923, a full six months before tenders closed for the construction contract. This marked the start of work on the approaches to the bridge.

Construction on the actual span did not begin until the laying of the foundation stone for one of the southern abutments on 26 March 1925.

The four abutments are the load-bearing foundation of the bridge and from these the arch, which supports the road and rail deck, was built outwards simultaneously from the north and south.

The granite for the foundations and the distinctive pylons that rise from the abutments was quarried at Moruya on the south coast of NSW. More than 250 stonemasons and their families, mainly from Scotland and Italy, were brought to Australia to work in the quarry.

Arch construction began on 26 October 1928. The steel for the bridge was primarily sourced from Dorman Long’s mills in Redcar, England, with the rest coming from BHP’s mill in Newcastle, NSW.

In total more than 52,800 tonnes of steel were used; 39,000 tonnes in the arch alone. The steel was fabricated into girders onsite in two large workshops built at Milson’s Point, on the site of present day Luna Park.

Slowly the main span of the bridge was erected by cantilevering the two half arches towards each other from each shore. The arches were stabilised by 128 steel cables anchored in tunnels excavated into the bedrock on each embankment.

Two halves joined

On 19 August 1930 the two halves of the arch were joined, making the bridge self-supporting and allowing the cables to be removed.

With the span complete, vertical hangers were attached to the arch and from these the bridge deck could be built.

The deck was completed in June 1931. The road, rail, water, drainage and gas lines were laid onto the deck over the next year.

Load testing began in January 1932 with 96 locomotives lined up end to end across all four of the bridge’s rail tracks.

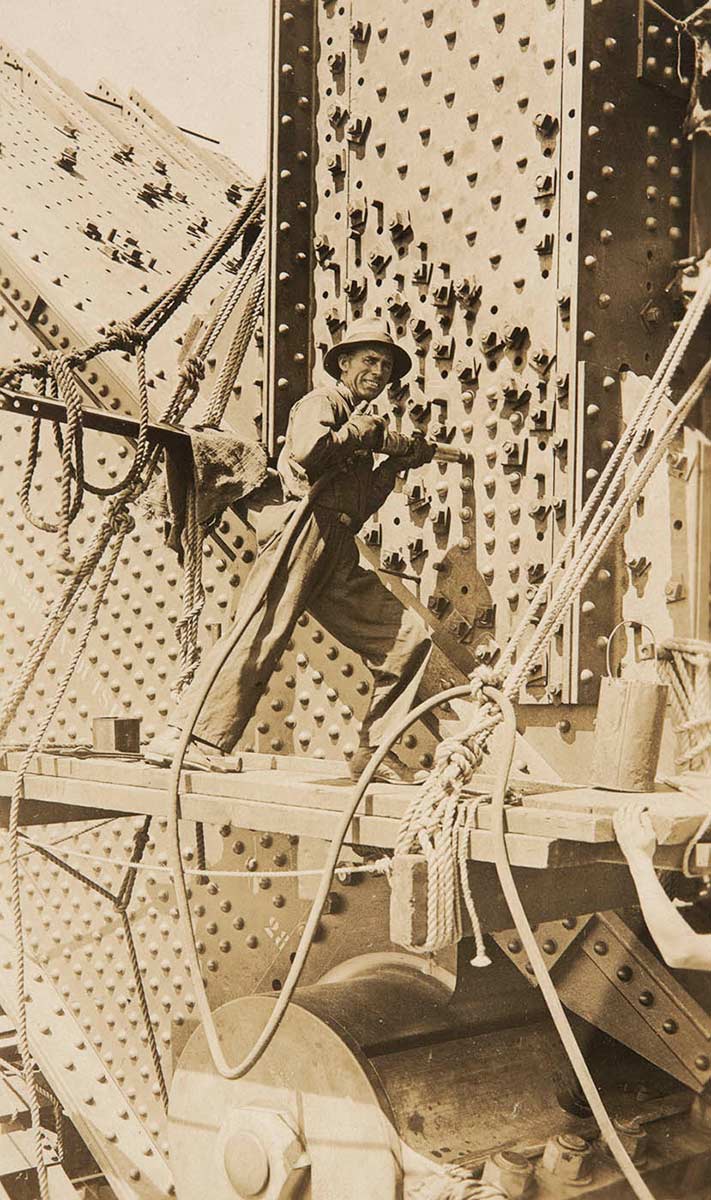

Workforce

More than 1,600 people worked on the bridge during the nine years of its construction, providing much-needed jobs for Sydney during the Great Depression.

However, it was hard, dangerous work, and as Lawrence Ennis, the Director of Construction, stated in 1932: ‘Every day those men went on to the bridge, they went in the same way as a soldier goes into battle, not knowing whether they would come down alive or not.'

By today’s standards industrial safety on the work site was poor. During the construction of the bridge, 16 men died.

Official opening

The official opening of the bridge took place on 19 March 1932. By that time 52,000 school children had already crossed the bridge in a series of ‘school days’.

More than 750,000 people gathered around the harbour for the official opening event. The bridge was to be opened by the New South Wales Premier, Jack Lang.

Before Lang could cut the ribbon and declare the bridge open, Francis De Groot, a member of the ultra-right-wing New Guard group, rode a borrowed horse out of the crowd and slashed the ribbon with his cavalry sword.

De Groot was arrested. Lang cut a new ribbon, the bridge was declared open, and a public bridge walk took place. De Groot was fined £5.

Legacy of the bridge

The cost of building the bridge was £4,238,839, although with the costs of constructing the approaches, the land resumptions, and interest paid during construction, the total cost of the build was closer to £10 million. The debt was finally paid off in 1988.

The Sydney Harbour Bridge has become one of the most recognisable icons, along with the Sydney Opera House, of Sydney and Australia.

The bridge undoubtedly made Sydney and its suburbs a much more connected city. In 2017, the bridge handles more than 200 trains, 160,000 vehicles and 1,900 bikes per day.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

D Ellyard and R Wraxwrothy, The Story of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Bay Books, Sydney, 1982.

Peter Lalor, The Bridge: The Epic Story of an Australian Icon: The Sydney Harbour Bridge, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2005.

Caroline Mackaness (ed), Bridging Sydney, Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales and Thames and Hudson Australia, Sydney, 2006.