More than 100,000 people worked on the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme from its launch in 1949 to its official opening in 1972. Migrants from more than 30 nations made up about 65 per cent of the workforce.

The scale of ‘the Snowy’ was enormous. Over the course of the project, the workforce built seven power stations, 16 dams, 80 kilometres of aqueducts, 145 kilometres of tunnels and 1,600 kilometres of roads and railway tracks.

The Snowy remains an important source of power and irrigation water today.

Prime Minister Ben Chifley, May 1949:

The Snowy Mountains plan is the greatest single project in our history. It is a plan for the whole nation, belonging to no one State nor to any group or section.

The history of the Snowy Mountains Hydro Scheme in live-sketch animation, as told by historian David Hunt

Postwar reconstruction

The trauma of the Second World War forced Australia to seriously reconsider its place in the world. Postwar reconstruction was a chance for the nation to reshape itself socially, economically and politically.

The Australian Parliament passed 299 Acts during the four years that the Chifley Labor government was in power. Major innovations included:

- a shift towards America in foreign policy

- a new, more inclusive approach to immigration

- the provision of unemployment and sickness benefits, widow’s pensions, Commonwealth scholarships and maternity allowances

- the introduction of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

- the production of the first mass-produced Australian car (the Holden FX)

- the formation of a national airline (Trans-Australia Airlines)

- the establishment of a national university.

All of these advances were designed to make Australia more independent and, in the case of immigration and industry, more defensible.

Increased industrialisation was to play a large part in the new Australia. State and federal governments promoted manufacturing to diversify away from the traditional sheep, wheat and minerals economy and maintain some of the heightened wartime industrial capacity.

To encourage this, Australia needed to develop a better and more consistent power supply.

Hydro-electric power

Electrical supply was limited in pre-war Australia and the expansion of wartime industry led to serious power shortages throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Federal and state governments were under pressure to find new electricity supplies.

Since at least 1894, coal-fired steam turbines had supplied the majority of Australia’s power.

This changed in 1916 with the development of a hydro-electric plant at Waddamana in central Tasmania and with the construction of a 100-kilometre high-voltage transmission line to Hobart, which showed that the power could be moved to where it was needed.

Hydro-electricity was now a viable alternative to coal power.

Snowy Mountains

The Snowy Mountains in southern New South Wales form the highest section of the Great Dividing Range, which runs from Victoria to Queensland. They are the source of some of Australia’s greatest rivers: the Murray, Snowy, Murrumbidgee and Tumut.

In 1937, in a report to the NSW Government on the electrical development of the state, the British engineering consultancy Rendel, Palmer & Tritton recommended building a 250-megawatt hydro-electric project on the Snowy River. However, the outbreak of the Second World War meant the proposal was not acted on.

In 1941 the newly elected NSW Government began an inquiry into the power-generating potential of the Snowy Mountains rivers and in 1944 a scheme was proposed to use the area’s water for power and irrigation.

This led to the formation of the Commonwealth and States Snowy River Committee, which began negotiations over water usage between the states.

Interstate rivalry leads to federal intervention

One of the problems with exploiting the Snowy Mountains’ river systems for power generation was that although the rivers rise in New South Wales, they run through Victoria and South Australia. Each of these states had their own views on how the waters should be used.

The limitations of the power system exposed during the war shifted public opinion towards using the water for electricity generation. However, New South Wales still argued that the primary purpose of any scheme should be irrigation while the federal government and Victoria wanted to prioritise power-generation with irrigation as a by-product.

All parties saw the additional water supply as a way to diversify the rural economy away from pastoralism and wool and towards more extensive fruit and dairy production.

The disagreements continued until the federal government declared the project a national security issue – Australia needed a reliable source of electricity away from coastal areas, which were vulnerable to attack.

The federal government introduced legislation under its defence powers and passed the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Power Act 1949. This led to the formation of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Authority (SMHEA), which would implement the power generation plan.

Snowy plan

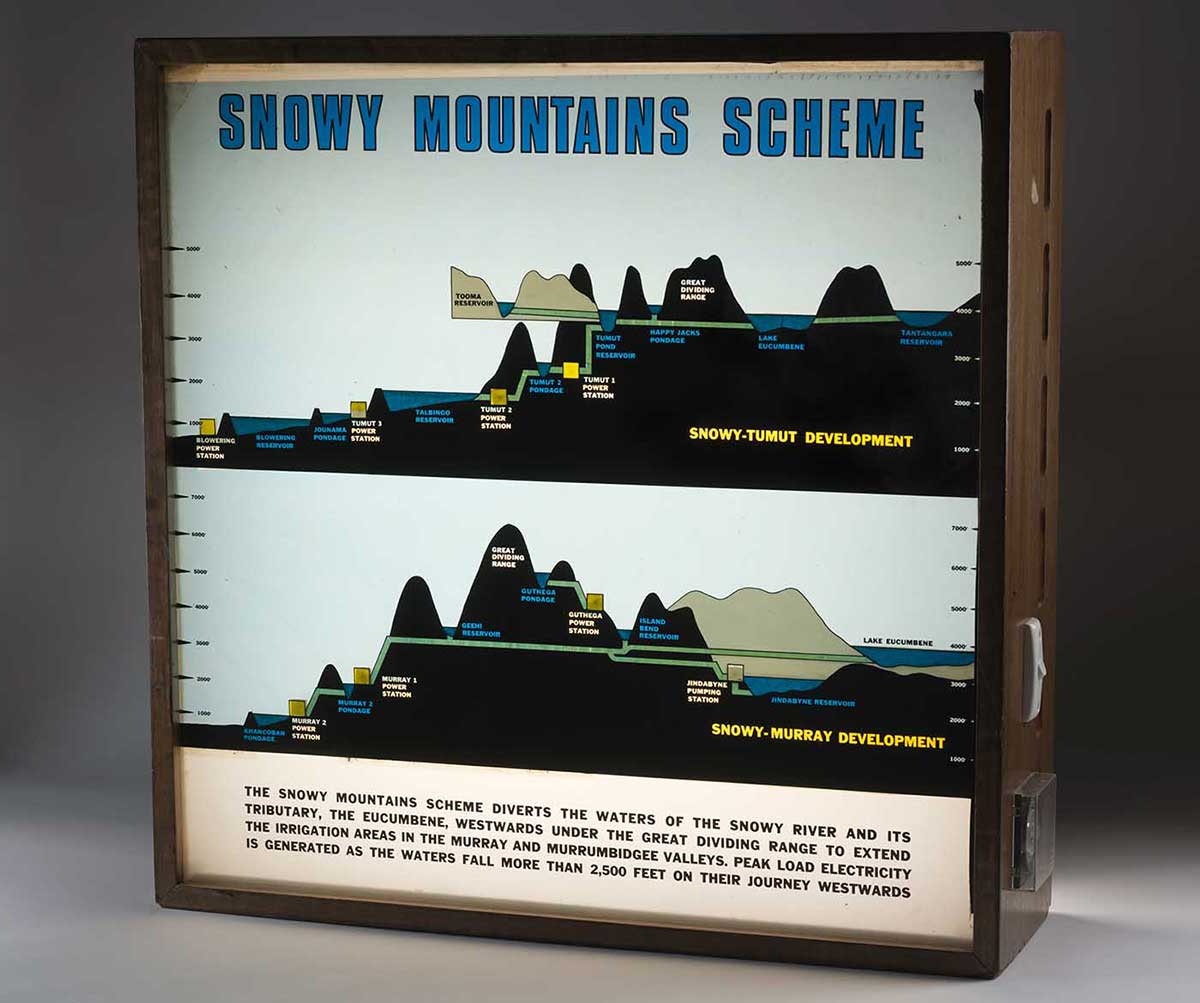

The final proposal, presented in November 1948, consisted of two physically separate projects – one in the north and one in the south of the Snowys.

The northern development would divert water from the Eucumbene, upper Murrumbidgee and upper Tooma rivers into the Tumut River. During their swift fall to the plains these waters would turn electricity-generating turbines in the Tumut Valley.

The water would then flow via the Tumut River into the Murrumbidgee for irrigation. The main storage for this system would be a reservoir formed by damming the Eucumbene River near Adaminaby.

The southern project’s water would be drawn from the Snowy River valley, diverted into the Murray and used to generate power in the course of its fall. A reservoir created by damming the Snowy River at the bottom end of the Jindabyne Valley would create the water storage for this section.

Snowy scheme as a multinational project

Construction started on 17 October 1949 when Governor-General Sir William McKell, Prime Minister Ben Chifley and Chief Engineer of the SMHEA William Hudson fired the first blast in Adaminaby. Chifley declared that Australia was ‘on the threshold of a new era of great industrial and rural development’.

Hudson and the government knew from the outset that Australia did not have the engineering or labour capacity to build the project and one of the chief engineer’s first jobs was to recruit qualified people from refugee resettlement camps in Europe to move to Australia and work for the project.

Ultimately, two-thirds of all Snowy staff were from overseas. During the 25 years of the project, more than 100,000 men and women from 32 countries worked for the SMHEA (with a peak labour force of 7,300 in 1959).

The scheme brought together thousands of people whose nations only years before had been fighting each other. These included British and Germans, Norwegians and Italians, Australians and Austrians, but as William Hudson said, ‘You aren’t any longer Czechs or Germans, you are men of the Snowy’.

This great influx of foreign skilled and unskilled workers all engaged in building Australia’s greatest piece of energy infrastructure had a positive influence on national attitudes and government policy towards non-British immigration.

Snowy scheme achievements and challenges

The project was officially opened by Governor-General Sir Paul Hasluck in 1972 (although work continued until 1974).

The scheme was ahead of schedule, and at a cost close to the 1953–54 estimate of £422 million. However, in the 25 years it took to build, 121 men were killed in industrial accidents.

The Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme was one of the most complex engineering projects in the world.

Between 1949 and 1974 the workforce built seven power stations, 16 dams, 80 kilometres of aqueducts and 145 kilometres of tunnels as well as 1,600 kilometres of roads and train tracks.

More than 100 temporary camps and seven townships were built to house the workers. Only two per cent of the scheme’s works are visible above ground.

The Scheme reached its designed output capacity of 3740 megawatts in 1974, and provides an annual average of 2.36 million megalitres of water for irrigation and other purposes.

The Snowy is not without controversy. The environmental issues around rerouting entire river systems and denying the Snowy River its natural flow rate are still a concern.

Snowy scheme as a Defining Moment

The Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme was a pioneering project. It required the development of new tunnelling, electricity-generation and -transmission technologies.

Snowcom, the first transistorised computer in Australia and one of the first dozen or so computers in the world, was designed and built by the University of Sydney in 1960 and used by the SMHEA in Cooma for the complex design calculations on the project.

The early construction contracts were won by multinational companies but the training they provided to local engineers meant that by the late 1950s Australian companies were skilled enough to compete for and win contracts. The Snowy was the catalyst for preparing a new generation of Australian engineers.

In 1967 the American Society of Civil Engineers designated the Snowy as one of the civil engineering wonders of the world.

The Snowy continues to generate power. By 2018 it was producing 32 per cent of all renewable energy available to Australia’s east coast mainland grid.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

You may also like

References

A Dictionary on Electricity – Contribution on Australia, 1996 (PDF 122kb)

Ben Chifley, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Sir William Hudson, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Brad Collis, Snowy: The Making of Modern Australia, Hodder and Stoughton (Australia), Rydalmere, NSW, 1990.

Siobhan McHugh, The Snowy, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 2003.