Smallpox has been one of humanity’s deadliest diseases, though it has now been eradicated.

There is still debate over how smallpox broke out in the Sydney area in 1789. The colonists had developed some resistance through earlier exposure to the disease.

However, the local First Nations peoples had not and its impact of them and First Nations people across the continent was devastating.

David Collins, Judge-Advocate of the colony, April 1789:

At that time a native was living with us; and on taking him down to the harbour to look for his former companions, those who witnessed his expression and agony can never forget either. He looked anxiously around him in the different coves we visited; not a vestige on the sand was to be found of human foot; ... not a living person was anywhere to be met with. It seemed as if, flying from the contagion, they had left the dead to bury the dead. He lifted up his hands and eyes in silent agony for some time; at last he exclaimed, `All dead! all dead!' and then hung his head in mournful silence

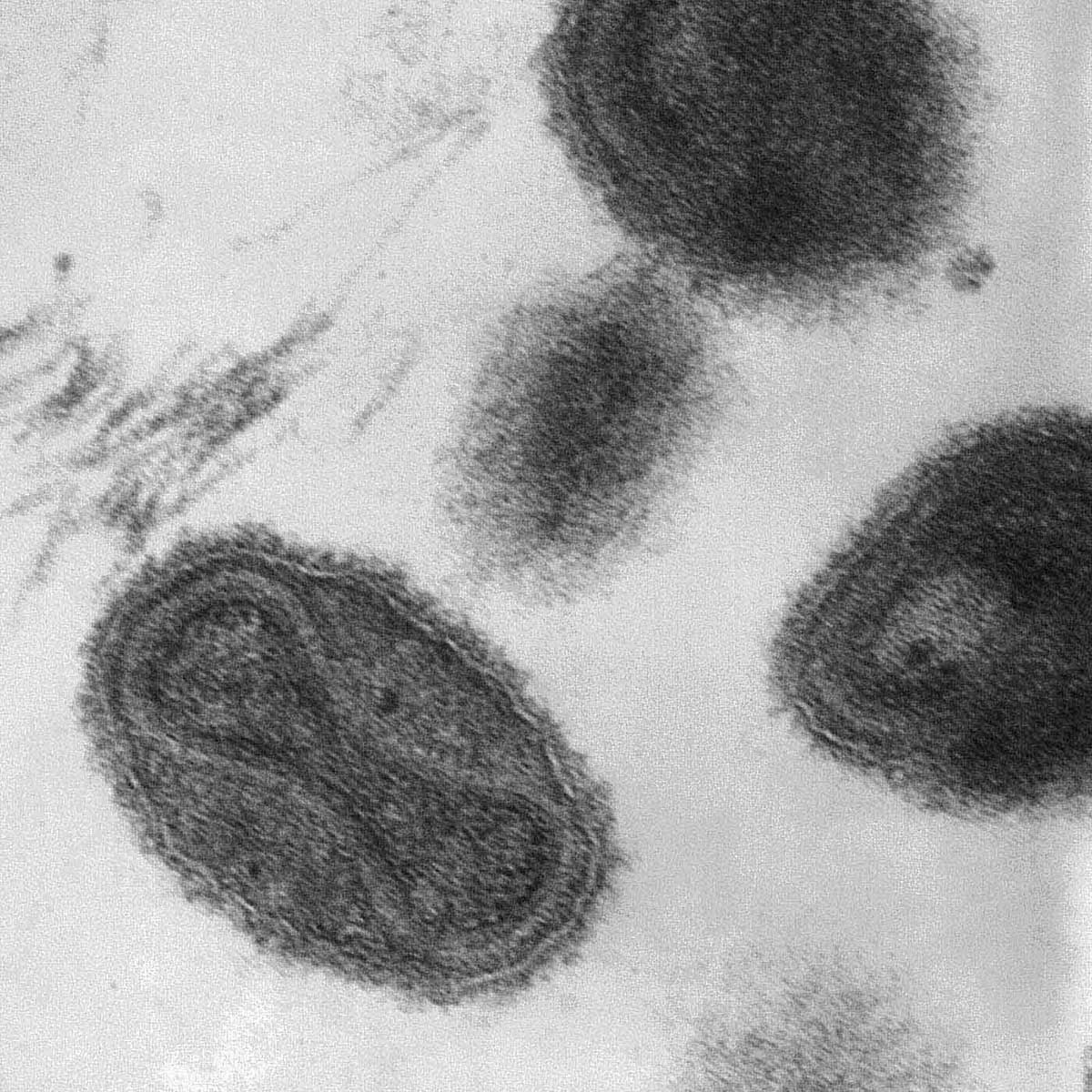

Smallpox

Smallpox is one of the most virulent and deadly diseases to have afflicted humanity. Throughout its long history, it infected hundreds of millions of people. Tens of millions of people died. Those who survived were often badly scarred, blinded or both.

Symptoms progress quickly and include fever, headache and backache as well as a severe pustular rash. Death can follow in a day or two.

The earliest evidence of the virus is in Egyptian mummies from the 3rd century BCE. The earliest written description of the disease appeared in China in the 4th century CE. Smallpox arrived in Europe in the 7th century with the Arab advance into Spain and Portugal.

Inoculation

About three out of 10 people infected with the smallpox virus died.

However, in China a technique called variolation, or inoculation, was developed where people were deliberately infected by having dried smallpox scabs blown up their noses.

Patients contracted a mild form of the disease with a mortality rate of only one to two per cent. Those who survived were then immune.

In 1717 Lady Mary Wortley Montagu learned of variolation in Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. In 1721 the Princess of Wales supported Lady Montagu in urging that the procedure be tested in England.

Prisoners and abandoned children had live smallpox virus, in the form of pus, inserted under their skin. They survived and several months later were exposed to the disease, which none of them contracted.

Variolation was then used across western Europe.

Arrival of smallpox in Sydney

In April 1789, 15 months after the First Fleet arrived to establish a penal colony in New South Wales, a major smallpox epidemic broke out.

The outbreak did not affect the British colonists, most of whom had been exposed to the disease during their infancy.

As a result, smallpox was not detected until members of the First Nations communities living between Sydney Cove and the Heads were found, according to Newton Fowell, ‘laying Dead on the Beaches and in the Caverns of Rocks’. They were, ‘generally found with the remains of a Small Fire on each Side of them and some Water left within their Reach’.

Without previous exposure to the smallpox virus, First Nations peoples had no resistance, and up to 70 per cent were killed by the disease.

The question of how smallpox appeared among the local First Nations groups was settled to the satisfaction of the early settlers by blaming the French. Explorer Comte de La Perouse had anchored his ships in Botany Bay for six weeks after the British first arrived. At least one of their company died during this period and was buried on the shore of the bay.

However, had the French infected the local population, the outbreak would have started in the early months of 1788, not more than a year later.

Subsequent commentators have suggested that unsuspecting Makasar fishermen brought smallpox to Australia’s north, after which it travelled down well-established trade routes.

However, given the relatively high population densities required for the disease to spread, and the fact that those infected quickly become incapable of walking, any such outbreak is unlikely to have spread across the desert trade routes.

A more likely source of the disease was the ‘variolas matter’ Surgeon John White brought with him on the First Fleet.

‘Variolas matter’ is pus taken from a recovering smallpox sufferer and sealed in a glass bottle to isolate and preserve it. White intended to use it to variolate any children born in the settlement. Research in the 1970s has shown that the smallpox virus withstands a wide range of temperatures and humidity and remains viable over many years.

How this material could have infected the local tribes is unknown. The appalling devastation it wrought probably silenced anyone in the colony who might have known.

Effect on First Nations peoples

Smallpox spread across the country with the advance of European settlement, bringing with it shocking death rates. The disease affected entire generations of the First Nations populations and survivors were in many cases left without family or community leaders.

The spread of smallpox was followed by influenza, measles, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases. First Nations peoples had no resistance to these diseases, all of which brought widespread death.

Vaccination and eradication

No cure for smallpox has ever been found, but in 1796 the English doctor Edward Jenner decided to test the countryside belief that milkmaids who had contracted the relatively mild disease, cowpox, were immune to smallpox.

He proved that it was true and from the cowpox virus he created the world’s first vaccine (from vacca, Latin for ‘cow’), which has since saved millions of lives.

The last smallpox case in Australia was identified during the First World War. However, smallpox continued to flourish around the world, particularly in poorer countries without access to the vaccine.

It was only in 1977 that the World Health Organization (WHO) eradicated smallpox in what is widely held to be the greatest public health achievement in the history of the world. The chairman of the WHO agency responsible for this was Australian Professor Frank Fenner.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

You may also like

References

Dr Jack Carmody on smallpox in the colony, ABC Radio National’s ‘Ockham’s Razor’, 2010

Noel Butlin, Our Original Aggression: Aboriginal Populations of Southeastern Australia, 1788–1850, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1983.

Judy Campbell, Invisible Invaders: Smallpox and Other Diseases in Aboriginal Australia, 1780–1880, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2002.

Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs and Steel: A Short History of Everybody for the Last 13,000 Years, Vintage, London, 1998.

Craig Mear, ‘The origin of the smallpox outbreak in Sydney in 1789’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, June 2008.

Jim Poulter, The Dust of the Mindye: The Use of Biological Warfare in the Conquest of Australia, Templestowe, Victoria, Red Hen Enterprises, 2016.