The Sex Discrimination Act was a largely successful attempt to ensure that women had the same access to jobs, services and accommodation as men.

It also made sexual harassment illegal for the first time in Australia and set up the Office of the Sex Discrimination Commissioner.

As such it helped redefine the role of women in Australian society.

The act was passed, despite vocal opposition from a minority of parliamentarians and public interest groups.

Susan Ryan, Minister assisting the Prime Minister on the Status of Women in 1984, writing in 2005:

The Act coincided with a defining moment in Australia’s social development … Australia was finally poised for progressive social change. In 1983, those defenders of the status quo who wanted no social change, recognised their last opportunity to prevent progress, and they gave it all they had. The Sex Discrimination Bill became the emblematic action that if allowed to succeed would change Australian society forever.

Whitlam government

In the late 1960s and 1970s women throughout the developed world were increasingly looking at their role in society.

Those women who did work outside the home typically occupied roles such as nursing, teaching and secretarial work.

A growing awareness of the inequalities faced by women was reflected in the United Nations decision to make 1975 International Women’s Year, and 1976–85 the Decade for Women.

Substantial changes to the actual rights and opportunities available to Australian women became government policy with the election in 1972 of Gough Whitlam as Prime Minister.

During its three years in office the Whitlam government brought in no-fault divorce and single mothers’ benefits, made the Pill more affordable, established the Family Court of Australia, and successfully lobbied the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission to grant women equal pay for work of equal value to men.

Dr Anne Summers on the importance of the Sex Discrimination Act

Whitlam created a national advisory committee and appointed Elizabeth Reid as his special adviser on women’s issues. Her role was particularly important at a time when there were still no women in Cabinet.

Reid convened the International Women's Year National Advisory Committee, led Australia's delegation to the International Women's Year Conference in 1975, and represented Australia at the United Nations forum on the Role of Women in Population and Development in 1974.

However, Susan Ryan, who became a senator in 1975, describes Australia in the mid-70s as having one of the most gender-segregated labour markets of any developed country – women were locked by discrimination into an employment and pay ghetto.

Industrial jurisdictions had accepted the principle of equal pay, but the work ghetto, limited education and training, and the meagre provision of childcare meant that women’s earnings were considerably lower – about two-thirds – of men’s.

Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women

The UN adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1979.

The Fraser government ratified it in 1980. This was an important development that provided the constitutional basis for federal parliament to pass sex discrimination legislation by exercising its ‘external relations’ powers.

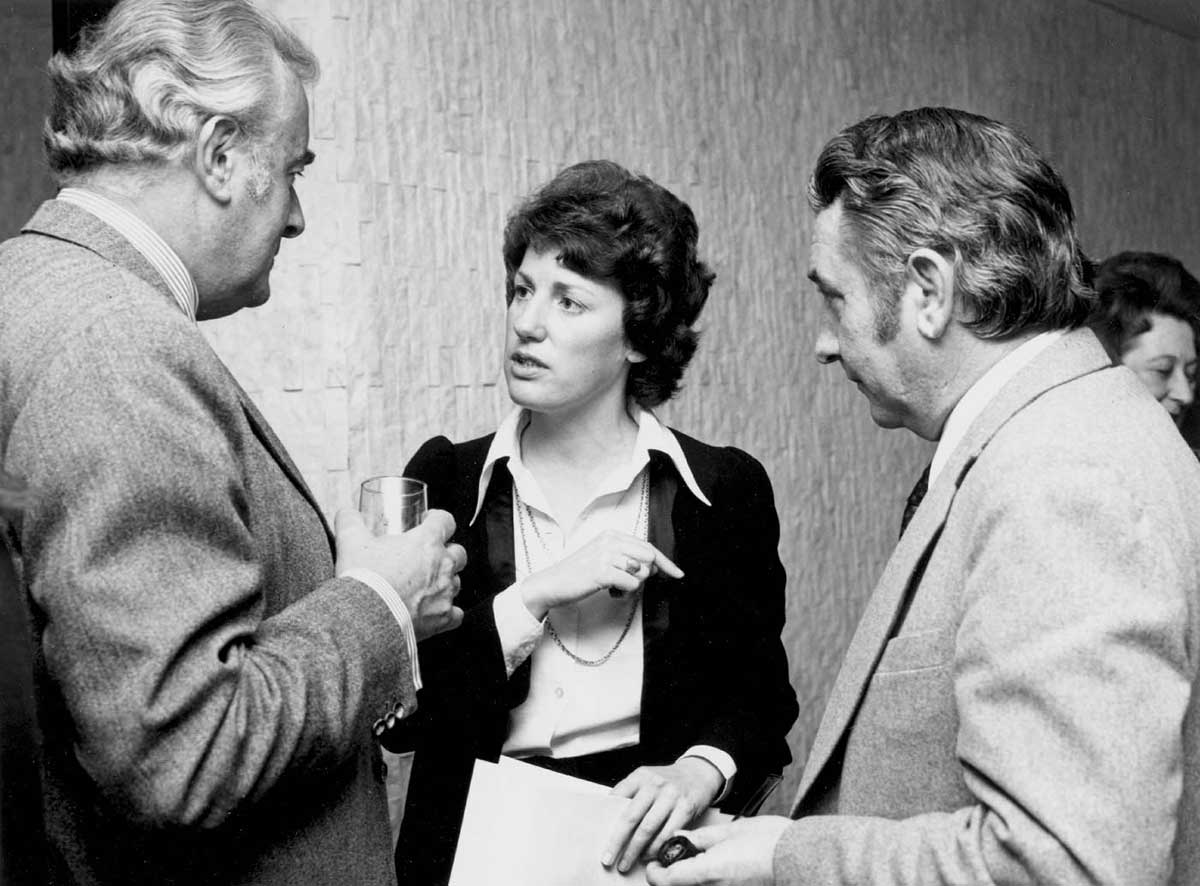

Susan Ryan

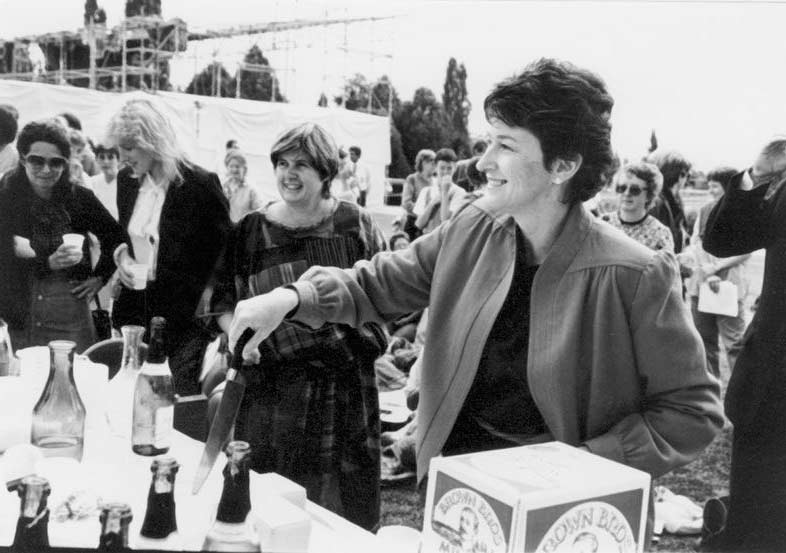

The Sex Discrimination Act was the brainchild of Susan Ryan, a former teacher and academic who was Senator for the ACT from 1975 to 1988.

She served in several ministerial portfolios in the Hawke government, making her the first woman to hold a Cabinet post in a federal Labor government. In 1983 Ryan was one of only 19 women in a parliament of 189 members and senators.

On 2 June 1983 Ryan introduced the legislation to the senate. In 1981, while in Opposition, she had tested the parliamentary waters by introducing a private members bill for sex discrimination, which was adjourned without a vote.

Legislation

The Bill extended to all areas of employment and education and many services, mirroring and building on existing laws in NSW, Victoria and South Australia.

The legislation was intended to promote equality between women and men by:

- prohibiting discrimination (both direct and indirect) based on gender when it came to employment, pay, promotion exclusion or unfair dismissal. This was later extended to marital status, pregnancy (or possible pregnancy) and breastfeeding.

- It also sought to protect women from discrimination when enrolling or studying at an educational institution, when seeking to rent or buy property, or accessing services such as banking and insurance, utilities, or government or professional services.

- It made sexual harassment illegal – the first time in Australia such protection had been legislated.

- Importantly, it also created the Office of the Sex Discrimination Commissioner. The impressive occupants of this position have often successfully kept issues of importance to women on the political and social agenda.

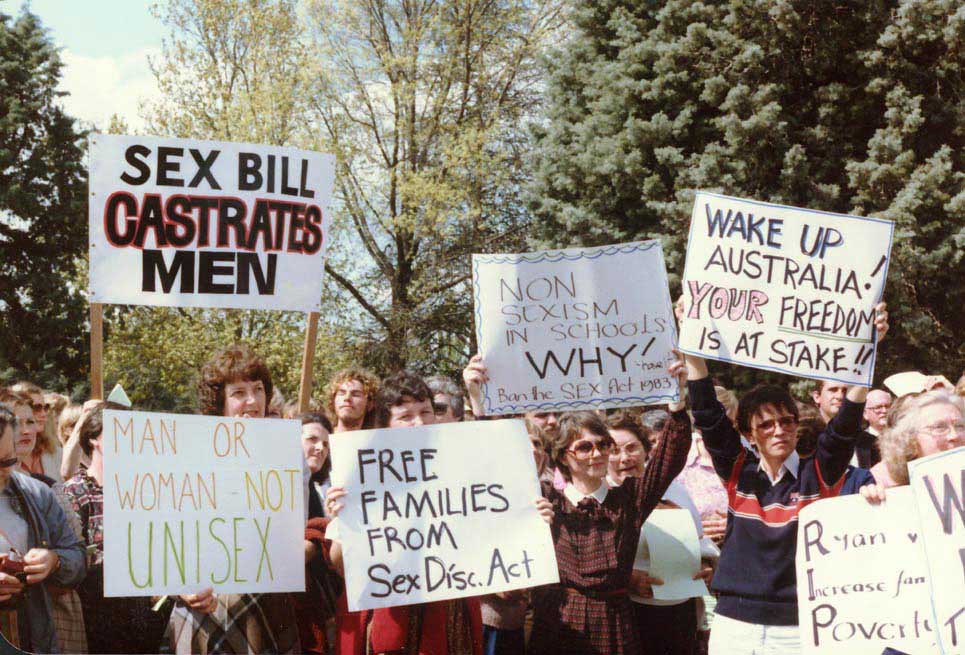

Protest

Though the principles underpinning the legislation seem entirely reasonable to most Australians today, the Sex Discrimination Bill met with, according to Susan Ryan, ‘sustained, vociferous and irrational opposition from powerful sectors of the community’.

Ryan found the extent of opposition surprising, especially given that the more contentious provisions of her 1981 private member’s Bill – the affirmative action measures – had been deferred for later legislation (passed in 1986), and that there was little new in the Bill apart from the sexual harassment provisions.

However, the government did not control the senate, and some members, such as independent senator Brian Harradine, had objections. This forced the government to make changes.

The superannuation and insurance sectors were given a temporary exemption to allow them to catch up with new regulations, and partial exemptions were provided for the church and the military.

Nonetheless, support for the bill was largely bipartisan and, after 17 hours of debate, it was finally passed.

The Act commenced on 1 August 1984.

Impact and limitations of the Act

The Sex Discrimination Act had a profound impact on women’s position in Australian society, in real terms and symbolically.

It encouraged more women to seek an education and employment, which raised families incomes. Women began taking more senior positions in the workforce and were promoted to more visible roles, and single mothers had more opportunities.

It made it possible for women to have both a work and a family life, and paved the way for further developments, such as paid parental leave.

However, the Act has certain drawbacks. Among these is the fact that it is complaint based, which means it is up to the aggrieved individual to lodge a complaint with the Australian Human Rights Commission, which offers conciliation services but does not have the power to, say, force an organisation to reinstate a person to their job.

For binding orders, a complainant has to go to the Federal Court or Federal Circuit Court – no small matter for someone who has lost their job or endured sexual harassment at work.

Some critics still say Australia has a long way to go in terms of true equality and representation. The numbers of women in parliament remains low, and they are under-represented in senior management positions, especially in the private sector.

Recent changes

In 2013 the Sex Discrimination Act was updated to provide more protections. It now covers sexual orientation, gender identity, intersex status and marital or relationship status. It has also expanded the definition of sexual harassment to include harassment because of any of the above.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

You may also like

References

Amendments to the Sex Discrimination Act 2013

Australian Human Rights Commission

Margaret Thornton (ed), Sex Discrimination in Uncertain Times, ANU Press, Canberra, 2010

Sex Discrimination Act 1984, Austlii

Susan Ryan writing on the Sex Discrimination Act in 2005, Centre for Policy Development

‘The Sex Discrimination Act after 25 years: What is its Role in Eliminating Gender Inequality and Discrimination in Australia?’ Insights Journal, University of Melbourne, Faculty of Business and Economics.