Twenty years to the day after the founding of New South Wales, the colony’s governor, William Bligh, was deposed by the New South Wales Corps.

The so-called Rum Rebellion was the first and only time in Australian history that military force has been used to overthrow a government.

Proclamation by Lieutenant-Governor George Johnston, 27 January 1808:

In future, no Man shall have just Cause to complain of Violence, Injustice or Oppression: – No FREE MAN shall be taken, imprisoned or deprived of his House, Land, or Liberty, but by the Law. Justice shall be impartially administered, without Regard to, or Respect of Persons; and every Man shall enjoy the Fruits of his Industry in Security.

Rum as currency in New South Wales

In 1806 William Bligh became the fourth governor of New South Wales.

At the time the colony had a European population of less than 7,000 and was struggling to survive. There were regular food shortages, the colony possessed very little infrastructure and trade was limited.

Colonial officials in London had not provided the colony with enough currency, so trade was conducted using barter, promissory notes (IOUs) and coins from around the world.

In the absence of a single medium of trade, rum imported from India became the de facto currency – a commodity whose importation and distribution had been monopolised by the New South Wales Corps since the departure of Governor Phillip in 1792.

From Phillip’s departure until the arrival of his replacement, Governor Hunter, the colony was administered by the Corps commanding officers – Francis Grose, December 1792 to December 1794 and William Paterson, December 1794 to September 1795.

During this time the Corps controlled the colony’s economy.

New South Wales Corps

The Corps was formed in England in 1789 to relieve the New South Wales Marines Corps detachment that had accompanied the First Fleet. It was made up of almost 700 men.

The officers and men had come to the colony expecting better financial and living situations than they had had in England.

For the officers in particular, this meant land grants from the governor, access to free labour from assigned convicts and freedom to conduct lucrative trading.

The enlisted soldiers were not much different than the convicts – unskilled or semi-skilled men with few prospects in England.

The paymaster of the Corps during these years was the ambitious Captain John Macarthur who was instrumental to the colonial economy in this position.

The commanding officer of the Corps in Sydney at the time of Bligh’s governorship was Major George Johnston.

Governor William Bligh

Bligh arrived in August 1806 with orders to control the use of alcohol as barter, restrict trade monopolies and end corruption among the Corps. He arrived without any of his own soldiers for support and, like his predecessors, was a navy officer.

The first four governors, all navy men, had great problems controlling the army officers, who resented what they saw as the navy’s interference on land.

Bligh was competent, strong-willed and determined, but these qualities were not tempered by tact and charm. He had been sent because he was a disciplinarian, but that characteristic had contributed to the infamous Bounty mutiny.

Bligh and Macarthur

Bligh had been informed by his patron, Sir Joseph Banks, that Macarthur would be his main adversary. Macarthur was now a private citizen; he had resigned rather than face a court martial for attacking his commanding officer. He almost immediately clashed with Bligh over a provisional 10,000-acre land grant that the governor refused to confirm.

The relationship between the two men gradually worsened as Bligh tried to re-establish government control of the economy and justice system.

In trying to limit the rum trade Bligh forbade bartering and introduced regulations securing government control of ships in port.

Major Johnston disliked Bligh not only because of his attempts to erode the Corps’ rum monopoly but also because the governor showed open contempt for his unit’s officers and men.

John Macarthur trial

On 25 January 1808 Macarthur faced trial on various charges arising from his refusal to pay a fine. Presiding at the court was Richard Atkins, the colony’s judge advocate, and six Corps officers.

Macarthur refused to be tried by Atkins on the grounds that Atkins owed him money. Macarthur was supported in this by his six Corps former colleagues and Atkins departed for Government House, seeking help from Bligh.

The next day Bligh wrote to the six officers demanding they present themselves at Government House to face charges of treason.

Unwilling to do this, the officers summoned Johnston. When he arrived at the Corps barracks, he made the extraordinary decision to appoint himself lieutenant governor and arrest Bligh, though he had no legal right to do so. In this, he was no doubt heavily influenced by Macarthur.

Bligh deposed

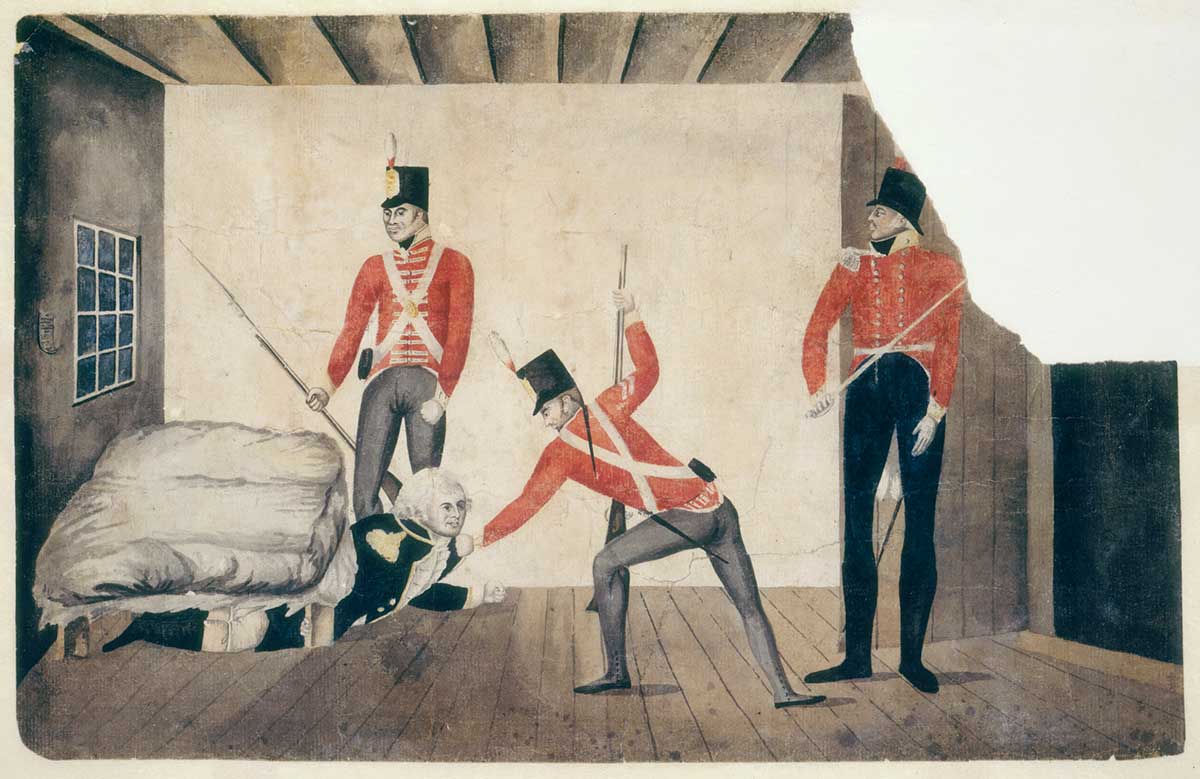

On the evening of 26 January 1808 Johnston marched almost the entire Corps to Government House where they found Bligh.

The legend that the governor was hiding under his bed was almost certainly started by the Corps.

Johnston and Macarthur took control of the colony, proclaiming they represented an end to Bligh’s ‘tyranny’.

Bligh remained under arrest in Government House with his widowed daughter for more than a year – refusing to return to England, despite being under pressure to do so – until relieved by a legally appointed successor.

In March 1809 Bligh, under duress, finally agreed to return to England, but once aboard his ship HMS Porpoise he reneged and sailed for Van Diemen’s Land where he sought help from its lieutenant-governor, David Collins.

Collins refused to help, so Bligh remained in Hobart for another year, mostly aboard the Porpoise, before returning to Sydney in January 1810, by which time the new governor Lachlan Macquarie had arrived.

Macquarie was an army officer and had landed with the 73rd Regiment, which replaced the New South Wales Corps.

In May 1810, Bligh finally sailed for England. Johnston and Macarthur had made the trip a year before in order to defend their actions and undermine the former governor.

Rum Rebellion aftermath

In London, the government decided that because Macarthur was a civilian he would have to be tried for treason in Sydney. Anxious to avoid this, Macarthur remained in England until, after lengthy negotiations, he received permission in 1817 to return to New South Wales without facing trial on condition that he take no further part in public affairs.

As a serving officer, Johnston did face court martial. He was found guilty and cashiered (dismissed from the Army), returning to Sydney in 1813 as a settler.

Bligh was largely, but not entirely, exonerated. He retired a vice admiral and died in 1817.

The Rum Rebellion remains Australia’s only coup d’état, though Bligh was by no means the only unpopular governor to have been deposed in Britain’s colonies during the 19th Century.

In our collection

Explore defining moments

References

Australian Dictionary of Biography entries for William Bligh, George Johnston and John Macarthur

William Bligh, Account of the Rebellion of the New South Wales Corps, Banks Society Publications, Malvern, Victoria, 2003.

HV Evatt, Rum Rebellion: A Study of the Overthrow of Governor Bligh by John Macarthur and the New South Wales Corps, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1938.

Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore: A History of the Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787–1868, Harvill Press, London, 1996.

State Library of NSW, 1808: Bligh’s Sydney Rebellion, SLNSW and Historic Houses Trust, Sydney, 2008.