On Saturday 4 October 1913 a fleet of seven brand-new grey-painted warships steamed out of the sea mist and through the Heads into Sydney Harbour.

The Royal Australian Navy’s new ‘fleet unit’ – a battlecruiser, three cruisers and three destroyers – had arrived.

The ships were a sign both of the new Australian Commonwealth’s maturity as a nation as well as Australia’s uncertainty as a ‘white’ dominion in Australasia.

Arthur Adams, ‘One Hour to Arm’, 1913:

Along the frontier of our North

The yellow lightning shudders forth; …Grant us an hour – to arm! …

Lord, in this lull before the break

Of Thy wide tempest, let us makeOur ramparts round complete.

With noise of rivets, whirr of wheels,

And waters hissing 'neath the keelsOf our star-guerdoned fleet!

Commonwealth Naval Forces

At Federation, the new Commonwealth inherited the ships of Australia’s tiny colonial ‘navies’ to form the ‘Commonwealth Naval Forces’ (which became the Royal Australian Navy in 1911).

Its mostly obsolete vessels essentially protected the waters around the state capitals’ ports.

The defence of the seaborne trade on which the island nation depended was the responsibility of the Royal Navy.

British warships, mostly paid for by Australian tax-payers, served on the Australia Station, part of a world-wide naval force controlled by the Admiralty in London.

White Australia policy

The new Commonwealth was founded on a deeply racist view of the world. One of the earliest acts passed by the new Australian Parliament was the Immigration Restriction Act 1901.

The journalist Charles Bean wrote in his paean to the new Royal Australian Navy that ‘for the good of either Australia or England, a Western and an Oriental race cannot live together in Australia’. Like many at the time, he anticipated that ‘the probability of an Oriental invasion, peaceful or warlike, is enormous, and justifies … steps to keep Australia white’.

This ‘White Australia’ policy was the foundation of Australians’ thinking about their nation’s future; and in the decade after Federation, that future seemed uncertain.

Japanese power

Australians in the decade following Federation were both optimistic and confident of their nation’s potential – but also apprehensive and even fearful.

As a small, self-consciously ‘white’ nation occupying a huge, sparsely populated continent on the fringe of Asia, many worried that they would become the victims of an Asian power they considered to be expansionist – Japan. The possibility of invasion influenced the broad debate about Australia’s defence.

British alliance with Japan

With its victory over Russia in 1905, Japan became a subject of obsessive interest to Australia. Journalists and politicians openly described Japan as a threat to white Australia.

The British alliance with Japan, formed in 1902 and renewed in 1905 and 1911, caused deep dismay in Australia. The alliance allowed the Royal Navy to concentrate in European waters to face the rivalry with Germany, leaving Japan as a growing major naval power in the Pacific.

Though overwhelmingly loyal to the British Empire, Australians were confused by Britain’s willingness to ally itself with a potential aggressor, and some became apprehensive about whether Britain could or would protect Australia from ‘the little brown cloud on the horizon’.

Australian fleet unit

In 1903–1913 Australian politicians gradually moved from simply accepting British assurances that the Royal Navy would protect Australia to acknowledging the necessity of self-reliance in defence. This decision reflected the evolution of a more assertive national identity.

It impelled Australian politicians to form a large citizen army, to court American protection and to create a large, expensive modern navy – named the Royal Australian Navy from 1911, by which time it had bought a ‘fleet unit’ of modern warships.

The British Government realised that the Royal Navy needed the dominions’ support to meet its global commitments. At the 1909 Imperial Conference ‘on the Naval and Military Defence of the Empire’, the British and dominion governments agreed that the Royal Navy would form ‘fleet units’ – what today we might call ‘battle groups’.

These comprised a force of cruisers, destroyers and submarines based around the newly developed ‘battlecruiser’, a fast and powerfully armed major warship.

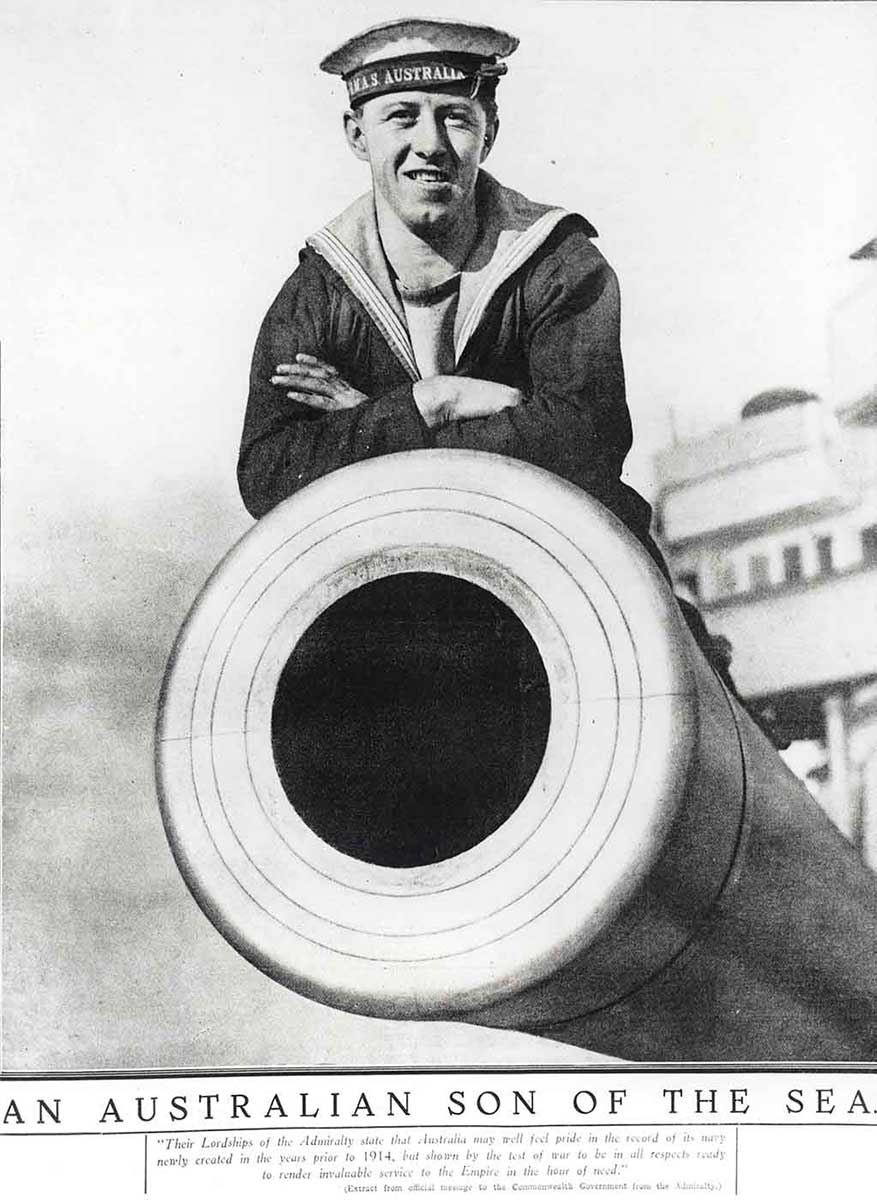

Australia was the only dominion to take up the invitation, and while it can be seen as a step in the resolution of Australian national self-reliance, it was, as Prime Minister Joseph Cook said at a celebration of the fleet’s entry into Sydney Harbour, actually ‘the Australian section of the Imperial Fleet’.HMAS Australia

The centrepiece of the fleet unit, and of its entry into Sydney Harbour, was the battlecruiser HMAS Australia.

The battlecruiser was a revolutionary new type of warship. It was three times larger than the new cruisers HMAS Sydney and Melbourne, it could steam at the speed of a cruiser but was equipped with guns almost as powerful as a battleship. It was, as the naval historian David Stevens wrote, ‘a ship for a nation’.

HMAS Australia

The centrepiece of the fleet unit, and of its entry into Sydney Harbour, was the battlecruiser HMAS Australia.

The battlecruiser was a revolutionary new type of warship. It was three times larger than the new cruisers HMAS Sydney and Melbourne, it could steam at the speed of a cruiser but was equipped with guns almost as powerful as a battleship. It was, as the naval historian David Stevens wrote, ‘a ship for a nation’.

Royal Australian Navy fleet

The entry of the Royal Australian Navy’s fleet unit into Sydney Harbour was, as naval historian Tom Frame writes, ‘by far the proudest moment in Australia’s short national history’.

While the formation of a modern fleet did indicate the Commonwealth of Australia’s confidence in taking charge of its own defence, it also suggested more ambiguous currents in Australia’s conception of itself.

The ships were proudly named ‘His Majesty’s Australian Ship’ – a mark of the dual loyalty characteristic of the period. While the fleet unit was paid for and, in peacetime, administered by the Australian Government, it was understood to come under Admiralty control in the event of war, which followed less than a year later.

The creation of a national naval force was also a sign of the uncertainty that characterised a small ‘British’ nation that felt isolated and distant from the imperial homeland.

Explore Defining Moments

References

Charles Bean’s Flagships Three (1913)

Royal Australian Navy Sea Power Centre

‘“Gone to Navy”: Defending Australia’, Peter Stanley, in Michelle Hetherington (ed.) Glorious Days: Australia 1913, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2013.

The Search for Security in the Pacific, 1901–14, Neville Meaney, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 2009.

Invading Australia: Japan and the Battle for Australia, 1942, Peter Stanley, Viking Penguin, Melbourne, 2008.

The Navy and the Nation: The Influence of the Navy on Modern Australia, David Stevens and John Reeve (eds), Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005.

No Pleasure Cruise: The Story of the Royal Australian Navy, Tom Frame, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2004.

Australian Naval Administration 1900–1939, Robert Hyslop, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne, 1973.