In early 1966 Ronald Ryan was convicted of murdering a prison guard while escaping from jail and was sentenced to death under Victoria’s mandatory sentencing legislation.

While the Victorian Cabinet usually commuted death sentences, it refused to do so in this instance.

The decision led to widespread opposition from church groups, students, lawyers, media and everyday Victorians. Ryan was hanged anyway, becoming the last person to be executed in Australia.

Journalist Brian Morley, who witnessed Ryan’s execution:

It was terrible. To see a man brought out and put to death while we watched was just the most unearthly feeling, and horrible feeling that I’ve ever had.

Capital punishment in Australia

Between the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788 and the Federation of Australia in 1901, up to 1900 people were executed for their crimes.

The first took place on 27 February, just one month after the First Fleet arrived, when a convict named Thomas Barret was hanged for stealing food.

In the colonial era, state executions could be applied not only in cases of murder but also of sheep-stealing, forgery and burglary.

The application of the death penalty declined after Federation, and violent crime diminished. From 1901 to 1967 the states and territories executed only 114 people. The vast majority of these executions occurred in the first 20 years.

Only 15 people were executed between 1950 and 1967. The last of these was Ronald Ryan.

Ronald Ryan

Ryan was born in the Melbourne suburb of Carlton in 1925. His father beat him and his mother was a domestic servant who neglected him.

After stealing a watch at age 11, Ryan was sent to a school for ‘wayward and neglected boys’. He escaped three years later and settled with his mother and three sisters in regional New South Wales. There he worked as a labourer.

When he was 23 he returned to Melbourne, where he married Dorothy George. They had three daughters.

However, by 1959 his addiction to gambling had driven him to lead a gang that broke into shops and factories. The following year he was arrested and sentenced to eight and a half years’ jail.

Ryan was released on parole in 1963 but soon returned to crime. In November 1964 he was sentenced to eight years’ jail for robbery.

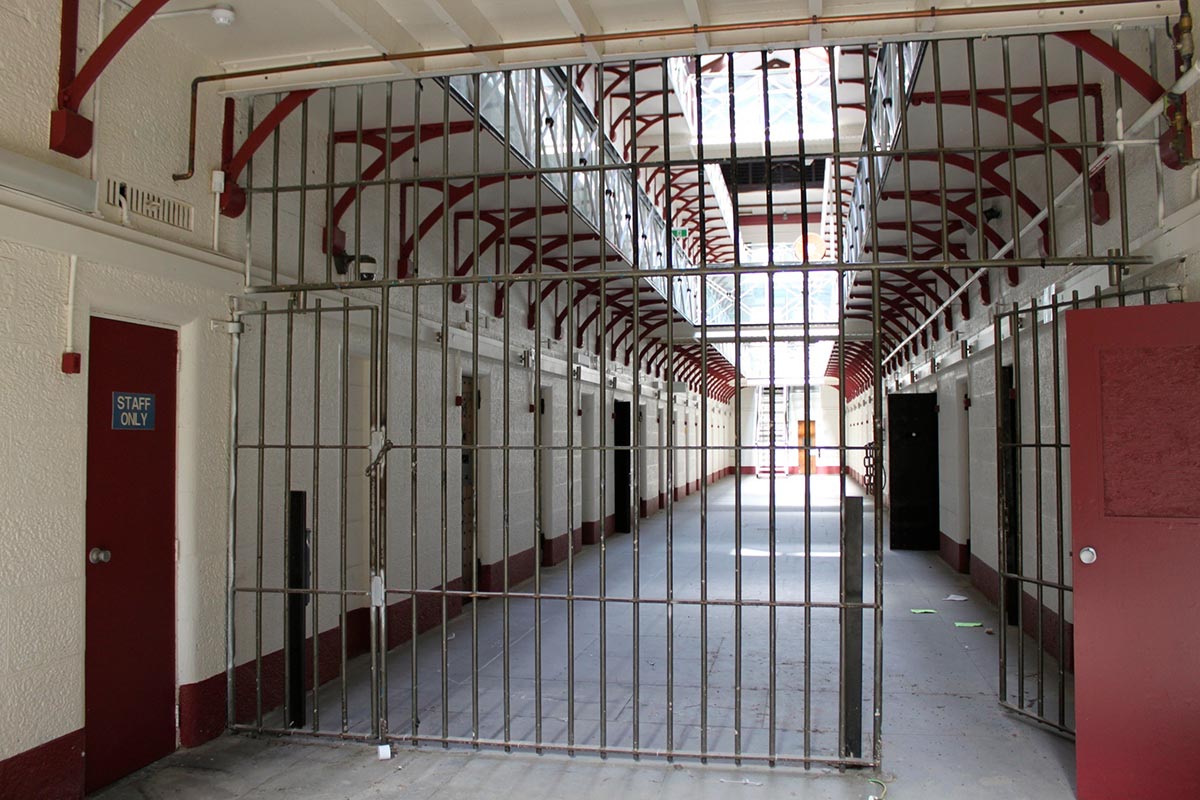

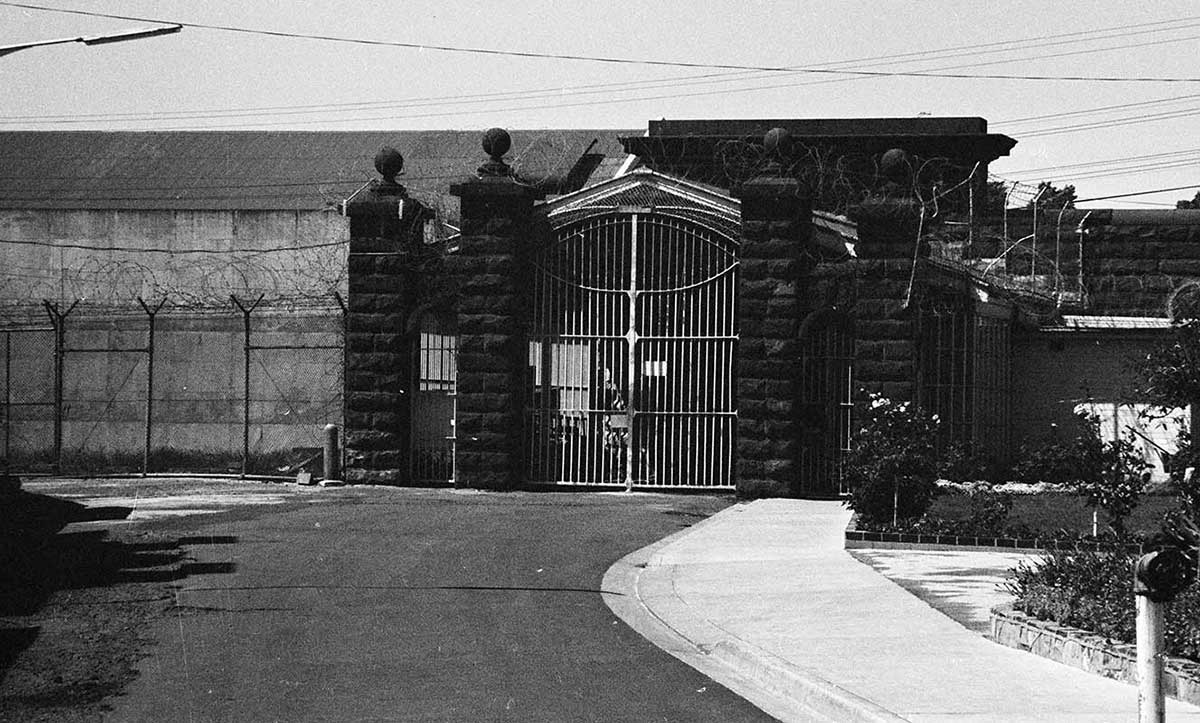

Less than a year later his wife divorced him and his daughters stopped visiting him. Despite being a model prisoner, Ryan decided to escape from Pentridge prison with another inmate, Peter Walker.

On 19 December 1965, while many of the guards were enjoying a Christmas party, Ryan and Walker successfully broke out. During the escape prison warder George Hodson was shot dead, either by Ryan or Walker – or possibly by one of the two guards who were shooting at the escapees.

Both men were at large for 17 days, causing widespread alarm, especially after they robbed a bank and Walker killed a tow-truck driver who recognised him. Following a tip-off, they were arrested outside Concord Hospital in Sydney on 5 January.

Ryan’s trial

At the trial Ryan and Walker pleaded not guilty to murdering Hodson. The jury deliberated for 12 days, and on 30 March 1966 convicted Walker of manslaughter and Ryan of murder.

The judge, Justice John Starke, was firmly against capital punishment, but he was bound by mandatory sentencing legislation to sentence Ryan to death. Walker was given 12 years.

Ryan’s barrister, Philip Opas QC, unsuccessfully appealed the decision in the Victorian Supreme Court and the High Court of Australia.

Sir Henry Bolte

While Ryan had received a death sentence, it was the convention for the Victorian Cabinet to commute it to life imprisonment. So it came as a shock to Ryan and the community at large when, on 12 December, long-serving Liberal Premier Sir Henry Bolte and his cabinet declared that Ryan would hang.

No one had been hanged in Victoria since 1951, although people had been hanged in Western Australia and South Australia as recently as 1964.

There has been a lot of speculation about Bolte’s motives. Perhaps he wanted to appear tough on law and order prior to the 1967 election. Or perhaps he was incensed by the embarrassment Ryan’s escape had caused his government. In any case, Bolte was determined to have his way.

Bolte refused to listen to any opposing views, even though they came from many sections of the community – ordinary people, church leaders, lawyers, universities, the federal opposition, Liberal MPs, the union movement, social welfare organisations and the media.

The Melbourne Herald, The Sun and The Age were all firmly opposed to the execution and campaigned intensively. Seven members of the jury that had convicted Ryan wrote to Bolte asking for clemency.

Barry Jones, leader of the Victorian Anti-Hanging Committee, later observed:

I doubt that Ryan had any intention to kill, but I am certain that Bolte did … ultimately, all executions are political.

Opposition to the sentence

Philip Opas took the case to the Privy Council in London (then Australia’s highest court of appeal). The appeal failed in January 1967. As Ryan’s legal options diminished, thousands signed petitions and university students mounted a round-the-clock vigil on the steps of Parliament House.

While protests were limited to Melbourne, almost every newspaper in the country editorialised against the sentence. Nationwide opinion polls showed support for capital punishment was at an historic low.

Ryan’s biographer Mike Richards wrote:

There was a new generation of Australians who had come to political maturity, and simply believed that hanging was barbaric in our time. They were more confident and assertive about articulating that view.

Ryan hanged

On the eve of the execution, hundreds of people gathered outside Pentridge prison, many of them remaining there all night.

Ryan’s daughters had not been allowed to see him before the execution.

Ryan was hanged in Pentridge at 8am on 3 February 1967. Official witnesses reported that he went to his death calmly.

Ryan’s body was buried in an unmarked grave on the grounds of Pentridge. His family members were forbidden from visiting his grave site. Only in 2007 did the Victorian Government give permission for his body to be exhumed and buried next to his ex-wife.

Banning of capital punishment

At the next Victorian state election, held less than three months after the hanging, Sir Henry Bolte was returned with an increased majority.

There is no doubt, however, that the strong opposition to Ryan’s hanging contributed greatly to the 1975 decision to abolish capital punishment in Victoria. The government, under Bolte’s successor, Sir Rupert Hamer, was the only Liberal government in Australia to do so.

Queensland abolished the death penalty in 1922, Tasmania in 1968, South Australia in 1976 and Western Australia in 1984. New South Wales abolished it in two stages, in 1955 and 1985, and the federal government did so for the territories in 1973.

Opinion remains divided on the issue to this day, particularly when it comes to terrorism and massacres such as the Port Arthur massacre in 1996.

Explore defining moments

References

Ronald Joseph Ryan, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Barry Jones’ Introduction to Barry Dickins, Remember Ronald Ryan, Currency Press, Sydney, (2nd ed.), 2014.

Mike Richards, Hanged Man: The Life and Death of Ronald Ryan, Scribe Publications, Carlton North, Vic., 2002.

Michael Victory, End of the Line: Capital Punishment in Australia, CIS Publishers, Carlton, Vic., 1994.