The first release of Cactoblastis cactorum moths into the Australian environment in 1926 is regarded as one of the world’s most spectacular examples of biological weed control.

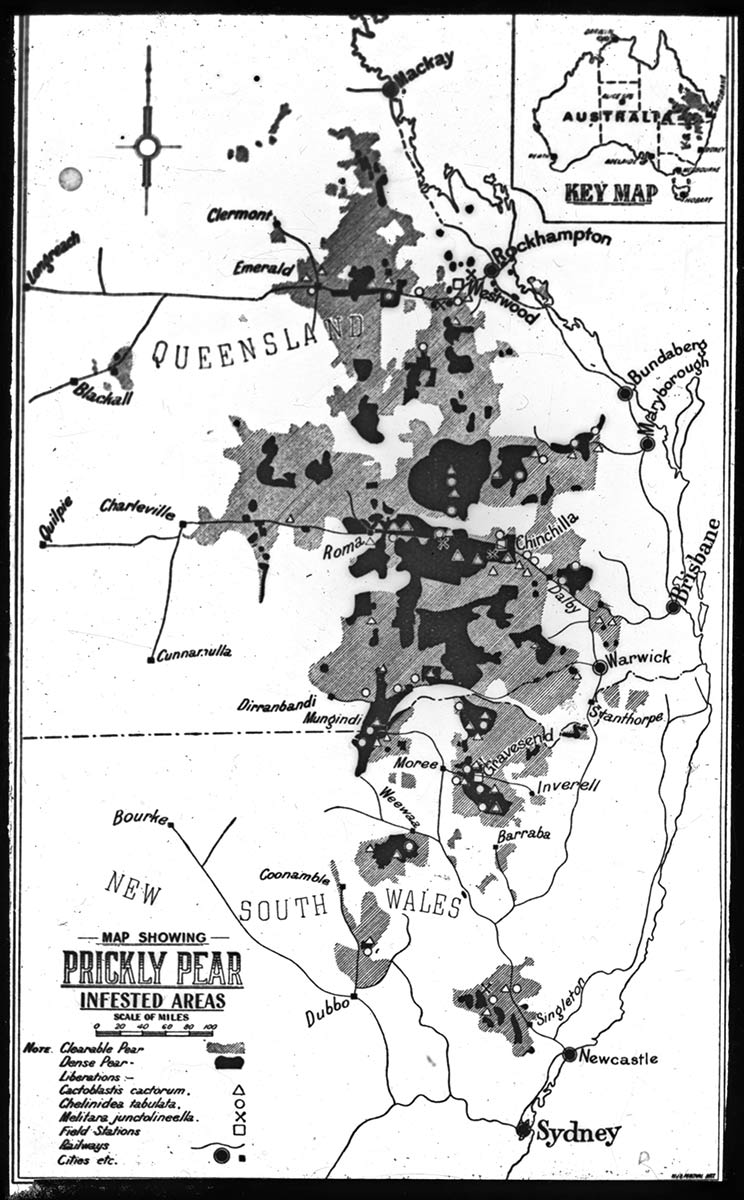

Before their release, prickly pear had overtaken 60 million acres (24.3 million hectares) of land in New South Wales and Queensland, making it unusable.

By 1933 it was estimated that 80 per cent of the infested land in Queensland, and 50–60 per cent in New South Wales, had been cleared.

Raymond Sandison, The Scone Advocate, 3 September 1954:

This was the turning-point in the fight against prickly-pear in Australia. Millions of eggs of the Cactoblastis insect were laboratory-reared and tested, and then dispatched to country areas for field-experiments. The results exceeded the scientists’ hopes. The caterpillars ate the insides out of the pear, leaving mere shells … and multiplied at a phenomenal rate.

Introduction of prickly pear

Prickly pear plants (most likely Opuntia monacantha) were introduced to Australia by the colonists of the First Fleet in 1788.

On board one of Captain Arthur Phillip’s ships was a collection of Opuntia plants, infested with cochineal insects (Dactylopius coccus), that had originated in Brazil.

A dye industry

Until the introduction of synthetic dyes in the late 19th century, crushed cochineal insects produced the brightest red dye in the world. This dye had been used in North and Central America for centuries before Spanish conquistadors discovered it in the markets there in 1519.

Spain quickly gained a profitable monopoly on the distribution of the dyestuff in Europe. During the colonial period it became Mexico’s second most valuable export after silver.

Red was the colour of authority, with kings and cardinals wearing red robes. The British army’s ‘redcoat’ uniforms became synonymous with the exercise of power.

Britain wanted a part of this lucrative market, and in the late 18th century Joseph Banks suggested establishing a cochineal dye industry in the subtropical colony of New South Wales.

The Brazilian cochineal insects soon died off, but the cactus plants survived. They are still found in coastal areas of New South Wales, where they are classified as a noxious weed.

Common pest pear

Opuntia monacantha variety did not spread beyond the east coast. Instead a number of varieties of the prickly pear were introduced to Australian gardens in the mid-1800s.

Settlers took plants to their properties across Queensland and New South Wales to be used as hedges and fodder during droughts.

The plants thrived in the dry interior climate west of the Great Dividing Range. The species which spread most prolifically were the common pest pear (Opuntia inermis) and the spiny pest pear (Opuntia stricta).

Government intervention

The first government action on prickly pear was in 1886 when the New South Wales Government passed the Prickly-pear Destruction Act. This legislation made the owners and occupiers of the land on which the plant was found responsible for its destruction. The Act also created the first government-appointed inspectors to oversee the law.

The 1886 Act was supplanted by subsequent Acts in 1901 and 1924, but none of the Acts were able to halt the advance of the prickly pear.

In 1901 the Queensland Government offered a £5,000 reward for an effective system to destroy the cacti. The reward was doubled in 1907, but nobody was able to claim it because none of the methods put forward proved successful.

Techniques for destroying the plants included burning the surface plants, digging them up, crushing them with horse-drawn rollers, and poisoning them.

The 1926 Queensland Prickly Pear Land Commission reported that 31,100 tins of arsenic pentoxide and 27,950 tins of Robert’s Improved Pear Poison (which consisted of a mixture of 80 per cent sulphuric acid and 20 per cent arsenic pentoxide) had been sold. But these hugely labour-intensive interventions were doing almost nothing to combat the spread of the cactus.

Prickly pear was becoming so dense that farming was impossible in many areas, and leasehold land was being abandoned.

A new approach

In 1913 the Queensland Government instituted a Travelling Commission, a team of biologists who visited countries in North and South America, where prickly pear was indigenous.

The commission determined that the plant there was being attacked by numerous insects and fungus diseases that appeared to be confined to the cactus family.

As a result, it recommended the introduction of a suite of natural insect and plant disease enemies to combat the prickly pear problem.

However, plans for the testing and release of these biological agents were put on hold after the First World War broke out in August 1914.

It wasn’t until 1920 that the Commonwealth, Queensland and New South Wales Governments established the Commonwealth Prickly-Pear Board (CPPB). The Board investigated the commission’s recommendations for controlling Opuntia stricta through biological agents.

Almost immediately, the CPPB sent a group of entomologists to America, under the leadership of Allan P Dodd, to acquire the previously identified biological agents. They simultaneously established a breeding centre for Cactoblastis cactorum moths in Queensland.

Cactoblastis cactorum

Cactoblastis cactorum moths are indigenous to a small area of Argentina.

Female moths lay their eggs on the prickly pear plants. Working as a team, the hatched larvae then eat through the tough outer layer of the cactus pads to get at the edible interior. There they feast on the soft tissue until they reach around 25 millimetres in length.

In a matter of weeks, the larvae can destroy an entire plant.

Once they have reached maturity, the larvae fall from the prickly pear and enter a cocoon stage. The moth hatches from the cocoon, and the cycle starts over again.

The release

The first two attempts to propagate moths in the early 1920s failed, so 3,000 Cactoblastis cactorum eggs were imported from Argentina. Half these eggs were sent to the Chinchilla Prickly Pear Experimental Station and half were kept in Brisbane.

From a population of 527 females, a total of 100,605 eggs were hatched. The moth was spectacularly productive. The second generation yielded over 2.5 million eggs.

In Chinchilla the moths underwent strict breeding and feeding assessments to ensure they would not attack other plants. In 1926 the first moth was released.

At the height of the operation, Chinchilla was sending out as many as 14 million cactoblastis eggs a day across Queensland and New South Wales. By 1933 most of the overgrown land had been cleared of the pest plants.

An ongoing problem

Although not on the same scale as the 1920s crisis, prickly pear continues to be a problem in New South Wales and Queensland, where new varieties that do not act as hosts for cactoblastis moths have become established.

In 1957 cactoblastis moths were introduced to the Caribbean, where Opuntia species are indigenous. The moths originated in South America and so the Caribbean plants had previously had no exposure to them.

They attacked the local species and from there progressed to Mexico, where they have started destroying Mexico’s commercial Opuntia crop.

In the United States there are grave concerns that the moths could destroy ecologically and economically significant Opuntia species right across the south of the country.

In our collection

Explore defining moments

You may also like

References

A prickly invasion, National Museum of Australia

Eradication of prickly pear in Australia, Nature

Terry Domico, The Great Cactus War: True Story of the Greatest Plant Invasion in History, Turtleback Books, Sydney, 2018.