Polio was among the most frightening diseases to affect Australians during the early 20th century.

The incurable and unpredictable viral disease mostly affected children and could cause permanent paralysis, even death. It sometimes reached epidemic proportions across the world.

Millions of doses of vaccine were distributed to Australians during robust national public health campaigns that began in 1956.

Routine immunisation over the following decades helped control the disease. Australia was declared polio-free in 2000.

The Central Queensland Herald, June 1956, on the introduction of the first polio vaccination campaign:

Within a few weeks from now thousands of our children will be immunised against the dread scourge of polio. It is a wonderful thing to think that if Salk vaccine does all that is claimed for it, Queensland will have no more polio epidemics.

Parents of immunised children will have a great load of fear lifted from them. The sight of scores of little polio victims in a convalescent or training home is a sight that one can never forget.

What is polio?

Poliomyelitis is a life-threatening disease caused by a gastrointestinal virus commonly spread through poor sanitation or contaminated food or water.

It is highly contagious. In most cases people with polio have no more than mild influenza-like symptoms. However, in a smaller number of people with the infection, the virus invades the nervous system, causing paralysis, usually of the spinal and respiratory systems. Of those affected in this way, five to 10 per cent die.

Polio generally affects children under five years old. Many survivors of childhood polio face lifelong consequences or can experience renewed effects later in life. This includes a neurological condition called post-polio syndrome.

History of polio

Populations across the world have experienced polio outbreaks since antiquity.

In 1789 British doctor Michael Underwood recorded the first clinical description of polio and in 1840 German doctor Jakob von Heine conducted the first study of the contagious disease. In 1908 studies by Austrian doctors Karl Landsteiner and Erwin Popper identified the disease as a virus.

Unlike other infectious diseases that declined as sanitation and hygiene improved, cases of polio increased in late 19th and early 20th century industrial societies. An unforeseen consequence of ‘cleaner’ surroundings was that babies, protected at first by acquired immunity from their mothers, had fewer opportunities to encounter and fight off the polio virus in its mildest form. They grew without developing antibodies of their own, leaving them vulnerable to the virus’s more aggressive effects.

At the time, it was not clear that the virus was spread orally. Many authorities shut down public places such as parks and swimming pools, especially during the warmer months when cases peaked. By the turn of the 20th century, several major outbreaks, particularly in American cities, encouraged research into this terrifying and unpredictable disease.

Nita Lawes, an 11-year-old Tasmanian schoolgirl who contracted polio during an outbreak in 1937:

The news items every morning in the papers were reporting about children getting sick with poliomyelitis. Very few people had ever heard of it, this crippling disease which paralysed your limbs and affected the lungs in many cases.

About a week after the schools closed, I didn’t feel very well. Even though I felt so ill it never entered my mind that I had polio.

Isolation

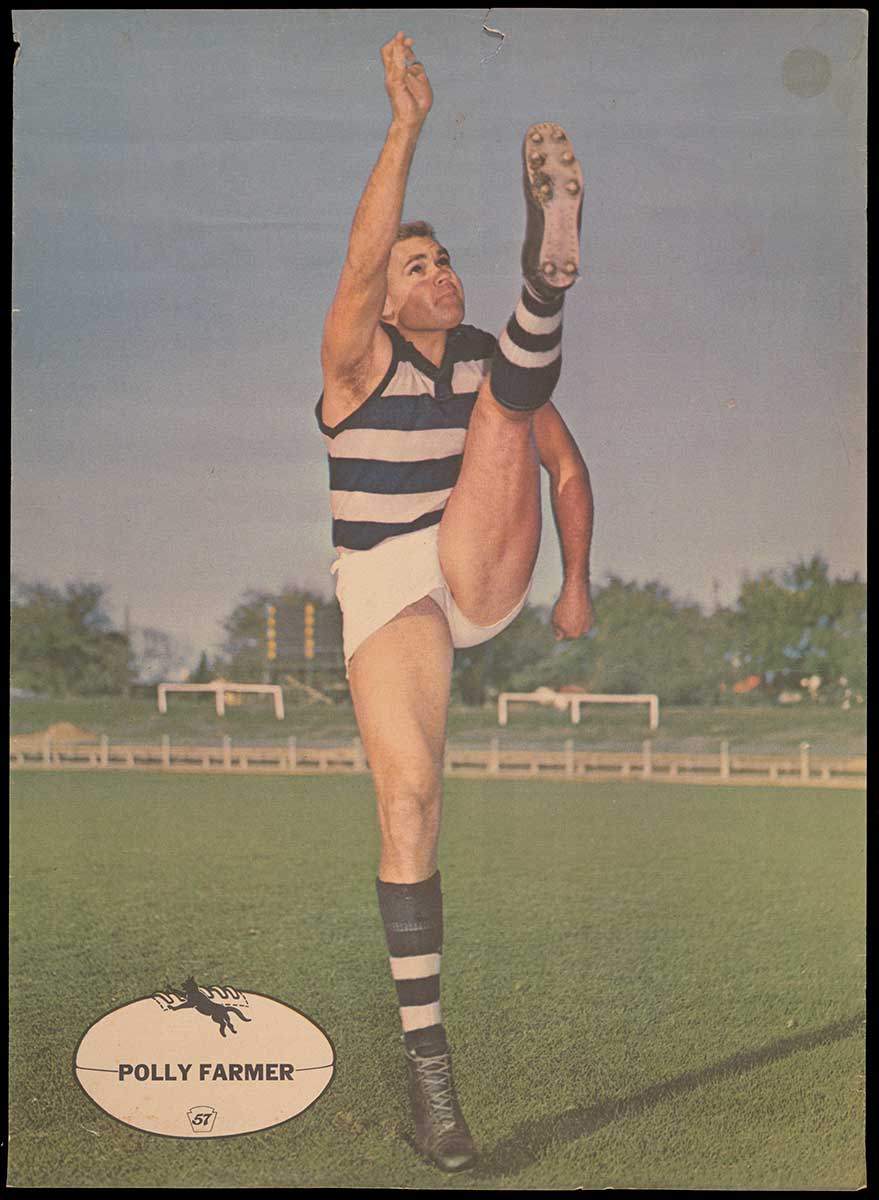

During the infectious period, people with polio were often isolated in hospitals or institutions with little or no contact with their families. Those who lived with ongoing disabilities often faced prejudice after leaving hospital, sometimes months or years later.

Marie Phibbs, who contracted polio as a baby in Albury, NSW, in 1954:

My mum was determined that she would do everything in her power to be able to give me as close to a normal life as possible. This was extremely hard … people were very nervous about contracting polio from each other.

Mum told me that if she took me up the street people would cross to the other side of the road if they saw her coming or say things to her like ‘she would be better off dead’. I cannot imagine how these types of things made her feel.

Polio treatment and aids in Australia

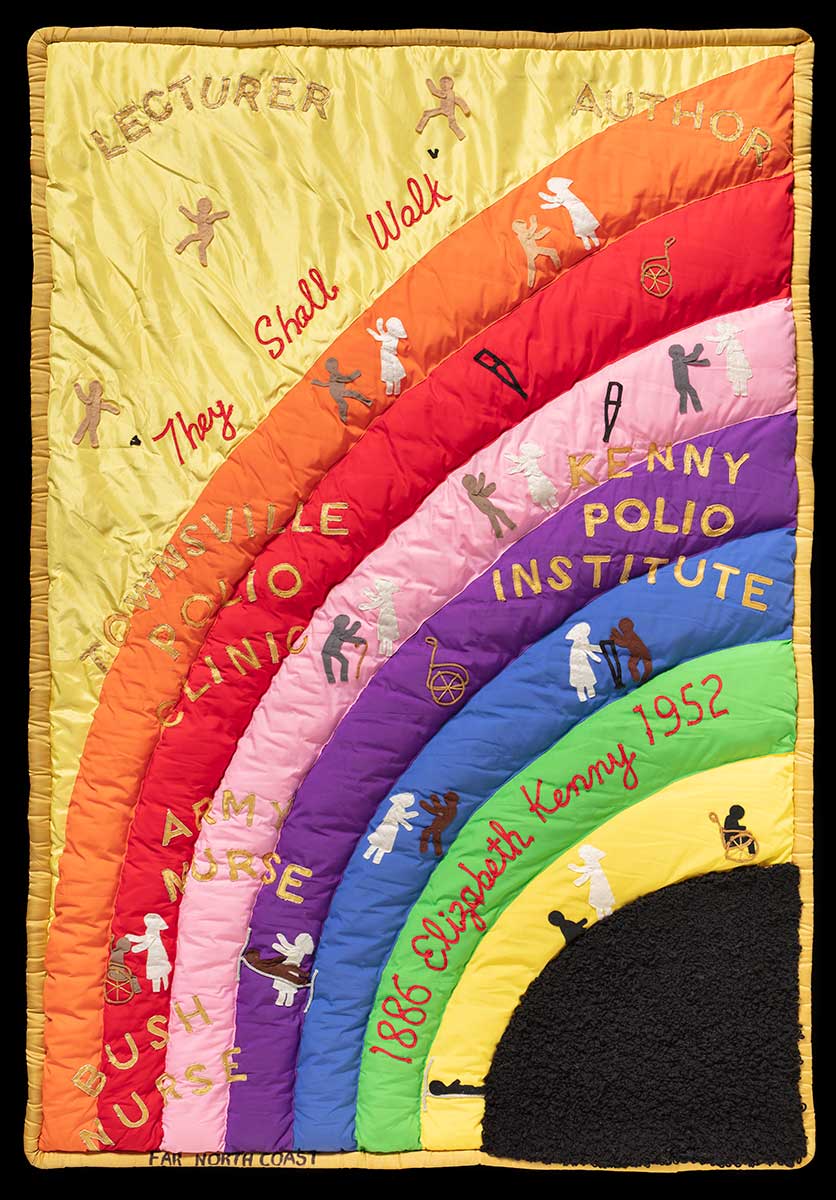

Several Australians responded to the polio crisis by developing innovative aids and treatments.

During the first decade of the 20th century, orthopaedic surgeon Colin MacKenzie designed shoulder splints for young polio patients using knowledge gained from specimens of koala musculature.

Large American-designed artificial respirators – known as ‘iron lungs’ – were built to accommodate those who were unable to breathe for themselves. As demand increased, South Australian Thomas Both designed a cheaper portable respirator made of laminated wood in 1937–38.

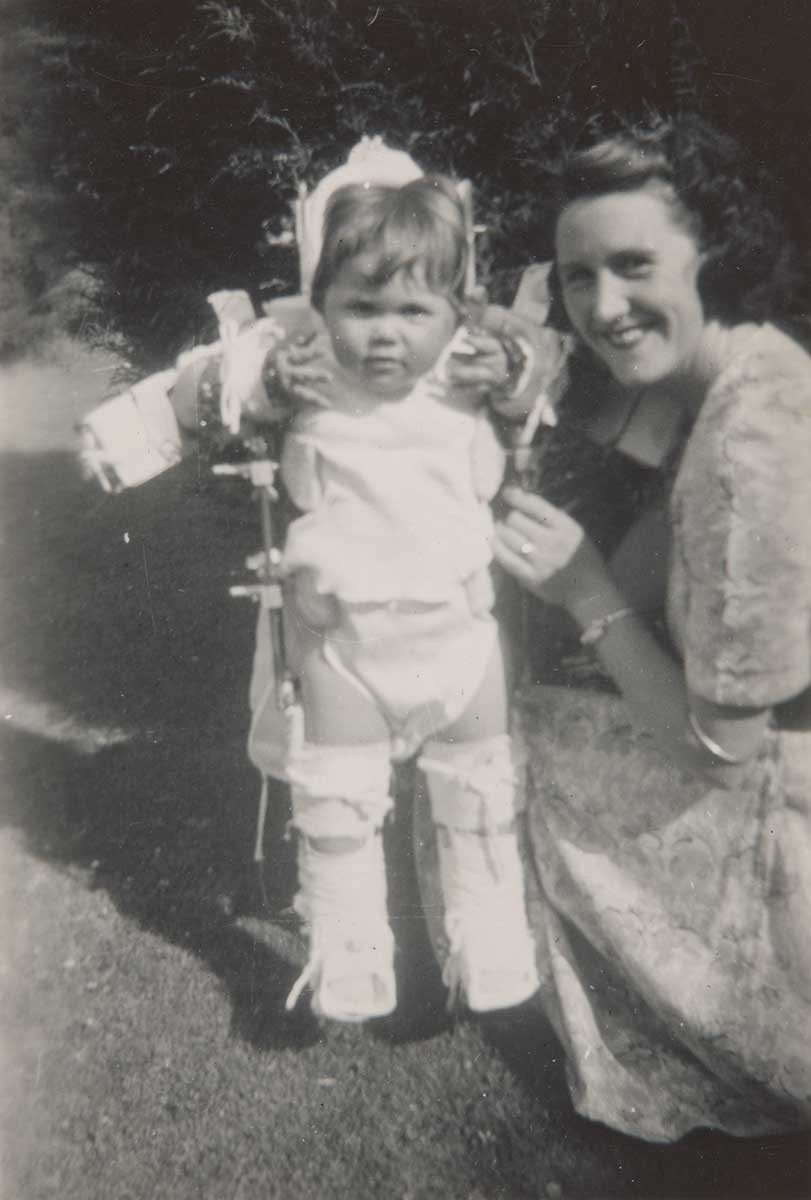

By the 1930s the most common treatment, as advocated by doctor and scientist Jean MacNamara, was to immobilise affected limbs using casts, braces, callipers and splints.

In 1932 Australian nurse Sister Elizabeth Kenny began a new method of treatment using warm compresses and massage, in what is now considered the forerunner of modern physiotherapy.

Both at home and in institutions, many survivors undertook months or years of painful treatments and rehabilitation to restore movement to nerve-damaged limbs.

Little formal support was available to parents of children with reduced mobility. Many required ongoing support from local medical services and used mobility aids.

Development of polio vaccine

It wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s that two Americans, Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, separately developed effective vaccines. In 1955 Salk and his research team at the University of Pittsburgh in the United States, developed the first injectable polio vaccine, known as inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV).

Dr Percival Bazeley, Director of the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL) in Australia was sent to America to work with Salk in 1952 and returned to Melbourne in 1955 to begin mass production of IPV.

Several Australian research institutions used children in institutions as subjects, during unethical vaccine trials prior to its widespread release.

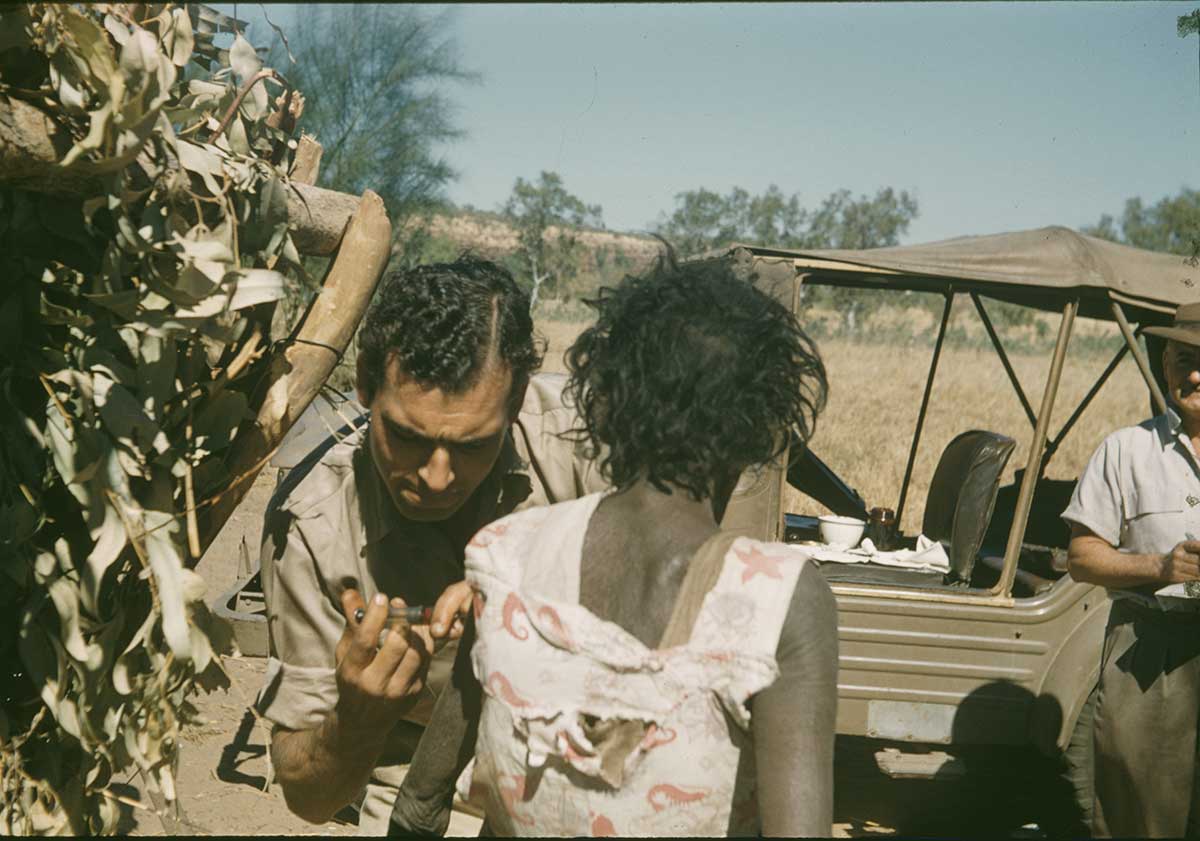

The first Salk vaccines were distributed to adults and children across Australia from July 1956. With the help of the Royal Flying Doctor Service, medical staff set up thousands of temporary clinics in regional and remote areas. More than 25 million doses of the vaccine were produced by CSL by 1966.

As vaccinations were administered, polio notification rates dropped significantly. However, ‘herd immunity’ – where the vaccination of a significant portion of a population provides protection for vulnerable individuals – took longer to establish. This contributed to another outbreak of polio in Australia in 1961 and 1962.

IPV was followed in 1961 by oral polio vaccine (OPV) developed by Dr Albert Sabin at the University of Cincinnati. The OPV was first used in Australia in 1966. Individual missions and schools often collated information on the distribution of vaccines, but the precise number of First Nations community members who received vaccines is unknown.

Polio eradication

By the 1970s, routine immunisation introduced worldwide as part of national immunisation programs, helped to control polio in many developed countries.

But during the early 1980s, polio remained prevalent in 125 countries. Australian Clem Renouf, then President of Rotary International, spearheaded the 1988 Global Polio Eradication Initiative, which resulted in the reduction of polio cases by 99 per cent.

Polio has been eradicated in most countries, but in the early decades of the 21st century, it remains endemic in Afghanistan and Pakistan. High immunisation levels remain crucial even in countries where polio has already been eliminated.

In October 2000 the World Health Organization declared the Western Pacific region, which includes Australia, polio-free. In 2022 there were, however, an estimated 400,000 polio survivors in Australia, many who still live with the long-term effects of the disease.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Wade Alexander, Sister Elizabeth Kenny: Maverick Heroine of the Polio Treatment Controversy, Central Queensland University Press, Rockhampton, Queensland, 2003.

Bill Bradley, Life after Polio: ... And I'm Still Stirring, self-published, Sydney, New South Wales, 2019.

Nita Lawes-Gilvear, Living with Polio: The Laughter and the Tears, self-published, Launceston, Tasmania, 1988.

David Piers Thomas, Reading Doctors' Writing: Race, Politics and Power in Indigenous Health Research, 1870–1969, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Acton, ACT, 2004.