Penicillin was the wonder drug that changed the world. It was the first antibiotic and proved an effective treatment against many diseases that are today considered relatively minor, but were more often than not deadly prior to its use.

Discovered in 1928 by Alexander Fleming, the drug was made medically useful in the 1940s by a team of Oxford scientists led by Australian Howard Florey and German refugee Ernst Chain. Penicillin has since saved countless lives.

Howard Florey, 1967:

The three of us got it together. That's to say, Chain, Fleming and me. And it was the first prize-giving after the war, so the Swedes put on a tremendous occasion ... Well, it's very, very gratifying, very gratifying indeed. But one should always realise that there's a terrible lot of luck in this sort of thing. We happened to have hit an antibiotic which worked in man. We could have worked with hundreds of others and they would have been chemical curiosities ... as long as one realises that most Nobel Prize winners look on themselves as being extremely fortunate, I think that's all I need say.

When a scratch could kill

Prior to the discovery and use of penicillin as an antibiotic, a simple scratch could lead to deadly infection. Streptococcus and Staphylococcus bacteria that infected small wounds like blisters, cuts and scrapes killed many people every year.

Many diseases that are treatable today (including conditions such as typhoid, strep throat, venereal disease and pneumonia) were responsible for numerous deaths, as options for treatment were, at best, extremely limited.

Some poisonous substances, including arsenic and mercury, were commonly used to control disease and were themselves extremely harmful to patients.

Luck aids penicillin discovery

In September 1928 the bacteriologist Alexander Fleming returned to St Mary’s Hospital and Medical School in London after taking a holiday.

Before leaving, he had set a number of petri dishes containing Staphylococcus bacteria to soak in detergent. Fleming noticed that one dish had not been covered by detergent and had become contaminated with mould. This particular mould, Penicillium notatum, seemed to be producing a substance that was killing the bacteria around it.

Further tests conducted by Fleming confirmed the anti-bacterial properties of the substance he called ‘penicillin’.

Fleming was not able to extract and purify the active penicillin components and so was unable to make it medically useful. He published an article about his findings and the potential of his discovery in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology and then moved on to pursue other research interests.

Florey and the Oxford research team

In 1938 Howard Florey, an Australian scientist working in England, brought together a team of research scientists (including Ernst Chain) at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, Oxford University.

The team was looking for a new project and, after reading Fleming’s article, Chain suggested that they examine penicillin. Assisted by biochemist Norman Heatley, the Oxford team tried to purify and separate the active components of the mould.

Initially, extraction was difficult and only tiny amounts of penicillin were harvested. The team, especially Chain and Heatley, worked continuously on developing processes to better grow and harvest penicillin, even using bedpans as vessels to hold the protein mix that grew the spores.

Although there were eventually rooms full of penicillin producing mould in the school, output was not high enough to complete widespread trials.

Once positive tests were conducted on mice, the team tried treating humans on a small scale at the Radcliffe Hospital, initially with mixed results. After refining the trial process, it was discovered that penicillin was extremely effective in treating many conditions and infections that had previously proven fatal.

With the onset of the Second World War, the production of the drug for widespread use became their goal.

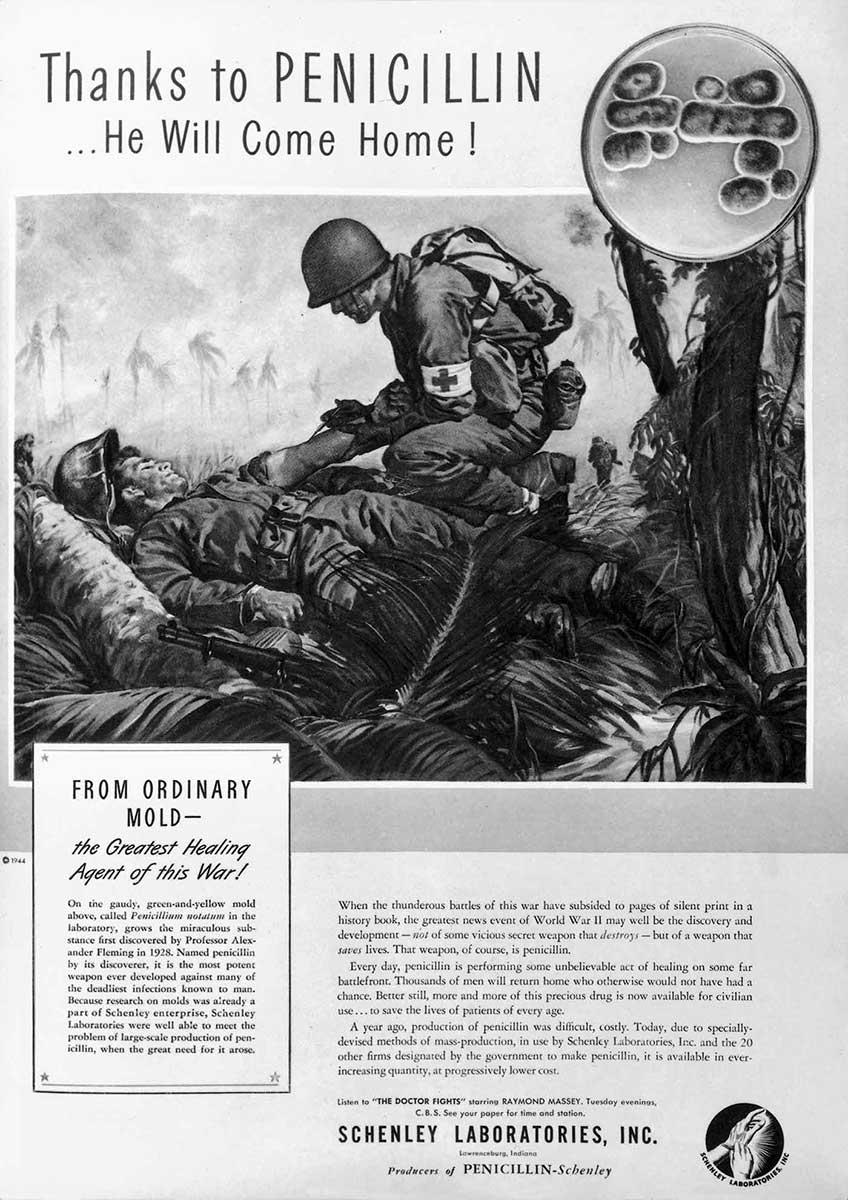

World War Two and penicillin

When war was declared in 1939, the Oxford team was not able to get enough support to begin large-scale manufacture and testing in Britain, despite the potential of their ‘wonder drug’. In 1941 the team approached the American government, who agreed to begin producing penicillin at a laboratory in Peoria, Illinois.

Further research was conducted to find new strains of penicillin that would provide higher outputs and make enough of the drug available for all Allied troops. Interestingly, the best strain was found growing on a rockmelon at a farmers market.

American pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer also began producing penicillin and the drug was in common use by Allied forces by the latter half of 1944.

Impact of penicillin

Penicillin saved thousands of lives during the Second World War and is considered one of the contributing factors to the Allied victory. After the war, the drug became available to the public and was used to treat otherwise fatal conditions. Penicillin essentially turned the tide against many common causes of death.

The development of penicillin also opened the door to the discovery of a number of new types of antibiotics, most of which are still used today to treat a variety of common illnesses. Without penicillin the development of many modern medical practices, including organ transplants and skin grafts, would not have been possible.

In 1945 Fleming, Florey and Chain received the Nobel Prize in medicine. Howard Florey has also been recognised many ways in Australia. There is a Canberra suburb named Florey, his likeness was on the 50-dollar note from 1973 to 1995 and there are a number of university research schools and fellowships named in his honour.

Explore Defining Moments

References

1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, The Nobel Prize

Lennard Bickel, Florey: The Man Who Made Penicillin, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1983.

Kevin Brown, Penicillin Man: Alexander Fleming and the Antibiotic Revolution, Sutton Publishing, Gloucestershire, 2004.

Robert Bud, Penicillin: Triumph and Tragedy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2007.