Two years after the arrival of the First Fleet, Aboriginal warrior Pemulwuy began to resist the incursion of white settlers onto his people’s traditional lands.

Despite being seriously wounded in 1797, he eluded capture until 1802 when he was shot dead. Pemulwuy’s head was cut off and sent to Sir Joseph Banks for his collection.

Governor King to Lord Hobart, Secretary of State for the Colonies, 30 October 1802:

Decided measures therefore became necessary to prevent the out-settlers from being robbed and plundered, and to restore the natives to a friendly intercourse. With these views (founded on the opinions of the principal officers coinciding with mine), I gave orders for every person doing their utmost to bring Pemulwye in either dead or alive …

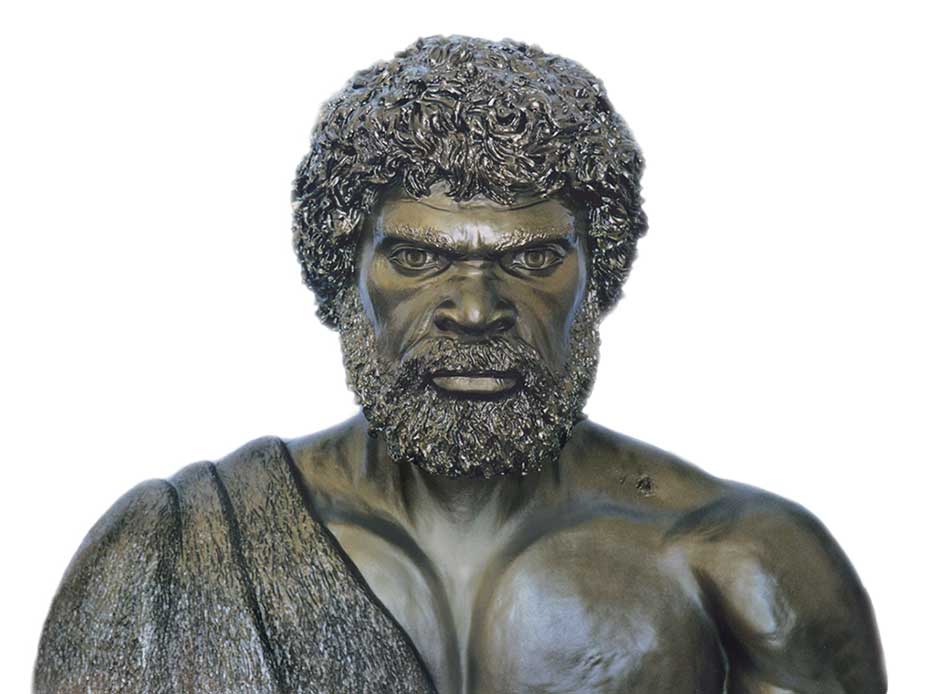

A remarkable man

Despite his reputation – both before and after his death – only a few firm facts are known about Pemulwuy (or Bembilwuyam). He was born sometime around 1750, and was shot dead on or just prior to 2 June 1802.

A Bidjigal (Bidgigal) man from the Botany Bay area of Sydney, his country ‘stretched from Botany Bay south of the Cooks River and west along the Georges River to Salt Pan Creek, south of Bankstown.’1

He had two distinctive physical features – one eye had a ‘speck’ or blemish, and one foot was clubbed. In Western medicine, the term clubfoot means a birth defect where the foot presents at an unusual angle. However, in Pemulwuy’s case, it was not congenital.

Another prominent Indigenous man Colebee explained that the injury was deliberately inflicted by a club, indicating Pemulwuy’s status as a carradhy or ‘clever man’ – that is, a man with supernatural powers.

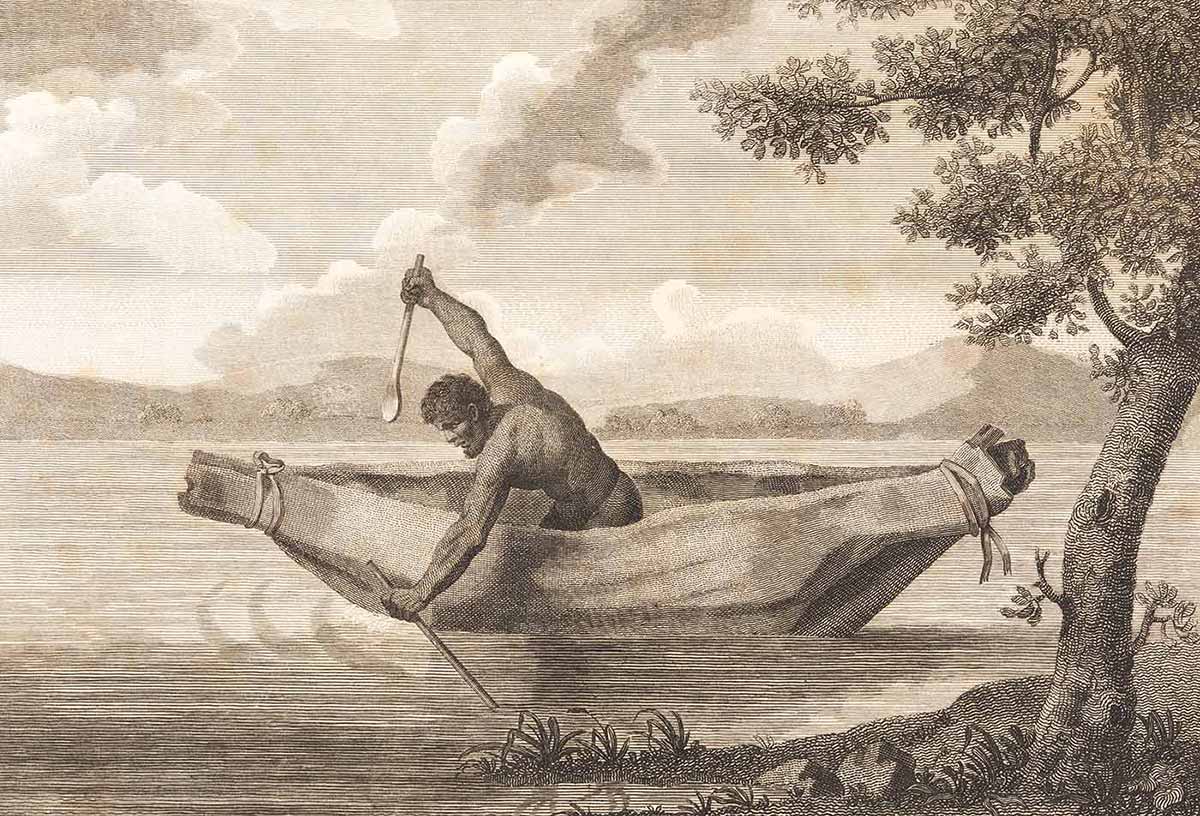

There is only one contemporary image that may be of Pemulwuy. The original image was by James Grant and has not survived. Samuel John Neele's engraving of Grant's image dates from 1803 – a year after Pemulwuy’s death. It shows him as being well-built and muscular. His feet are obscured and the detail of his face is limited.

Background to resistance

The Indigenous people of the Sydney area were faced with a profound change when the First Fleet arrived. Nearly 1500 people arrived on the fleet, with limited supplies of food, a cargo of foreign animals, sophisticated firearms, and a firm belief in their own superiority.

Governor Phillip initially maintained cordial relations, having been instructed to treat the ‘Indians’ (as they called the traditional owners of the land) well, and to ‘conciliate their affections …[and] maintain friendly relations’.

However, conflict was inevitable because of fundamentally opposed viewpoints. The Eora were the traditional owners of the lands around Sydney Harbour, and they had a complex system of laws that governed social relations, behaviour and resource use. The European invaders had no appreciation of this, and believed the Eora people to be savages.

An outbreak of smallpox in 1789, introduced by the European invaders, had a significant impact on the local people. The reduction in their population and the internal crisis it provoked temporarily averted open conflict. However, it was only a delay.

Disrupting colonisation

Pemulwuy featured significantly in the ongoing resistance to colonisation. He was involved in the mortal wounding of John McIntyre on 10 December 1790.

McIntyre, appointed Phillip’s gamekeeper on 3 March 1788, was one of three convicts armed and sent out to hunt game to add to the colony’s meagre and dwindling supplies of food.

The Australian Dictionary of Biography notes that McIntyre was ‘feared and hated by the Eora people’, and it surmises that the attack was a retribution for him breaking Indigenous laws and for his violence towards Indigenous people.

Phillip, who had until then been tolerant in his views, changed his position and called for a punitive raid. He sent 50 soldiers and two surgeons equipped with head bags.2 When that party failed to return with corpses, he sent them out again.

It was in response to this, and the growing attacks on his people’s rights, that Pemulwuy led a series of raids from 1792. The first was at Prospect in May 1792. The raids took place on Pemulwuy’s Bidjigal lands, and represent an attempt to retard the establishment of farming settlements.

The Bidjigal burnt huts, stole maize crops and attacked travellers. By April 1794, the violence between the Indigenous people and the farmers was frequent and extensive. In the ‘Battle of Toongabbie’, the reprisal party of Europeans severed the head of a slain warrior and took it back to Sydney as evidence.

The most substantial confrontation was the ‘Battle of Parramatta’. Pemulwuy, with about 100 Indigenous warriors, marched into Parramatta and threatened to spear anyone who tried to stop them.

Soldiers opened fire, at least five Indigenous men were killed, and Pemulwuy was wounded in the head and body by buckshot. But he managed to survive his wounds, and escaped a few days later, enhancing his already impressive reputation.

On 1 May 1801 Governor King issued a government and general order that Aborigines near Parramatta, Georges River and Prospect could be shot on sight. In November, a proclamation outlawed Pemulwuy and offered a sliding scale of rewards for his death or capture:

To a prisoner for life or 14 years, a conditional emancipation. To a person already conditionally emancipated, a free pardon and a recommendation for a free passage to England. To a settler, the labour of a prisoner for 12 months. To any other descriptions of persons, 20 gallons of spirits and two suits of slops.3

Death of a warrior

The rewards worked. Either on or just before 2 June 1802, Pemulwuy was shot dead. His head was cut off and sent to Sir Joseph Banks in England for his collection. The current whereabouts of the head is unknown.

A week or so later, a dispatch arrived from Lord Hobart to Governor King lamenting the settlers’ treatment of the Aboriginal population: ‘Be it clearly understood that on future occasions, any instance of injustice of wanton cruelty towards the natives will be punished with the utmost severity of the law.'4

Just who shot Pemulwuy remains a mystery. Following the work of Keith Vincent Smith, it has been generally assumed that Pemulwuy’s killer was Henry Hacking.5 Recent research by Doug Kohlhoff has queried this, suggesting instead that settlers from the Parramatta, Toongabbie and Prospect Hill areas were far more likely to have been the killers.

However, Kohlhoff asks whether, in the end, it really matters who killed Pemulwuy. At one level, it would matter greatly to Pemulwuy’s people. On another:

Knowing who fired the fatal shot does not affect Pemulwuy’s place in history. Pemulwuy was, as [Governor] King recognised, ‘a brave and independent character’. He inspired others, fought hard and died for his land and his people. For that, we can all admire him.

Notes

2 Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Crow’s Nest, Sydney, 2009, p. 394.

3 Government and General Order, Phillip Gidley King, 1801, Historical Records of New South Wales, 4, Hunter and King, p. 626.

4 Hobart to King, 30 Jan 1802, Historical Records of New South Wales, 4, p. 684.

5 Keith Vincent Smith, 'Australia’s oldest murder mystery', Sydney Morning Herald, 1 November 2003.

Explore Defining Moments

You may also like

References

Pemulwuy, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Pemulwuy, Dictionary of Aboriginal Sydney

Pemulwuy, Dictionary of Sydney

Dennis Foley, ‘Aboriginal leadership in crises’, series of two parts: ‘Part 1: Indigenous Australian leaders during the early frontier conflicts from 1788 to 1830’, (PDF 139kb) in Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues (1998), vol. 9, no. 4, Dec 2006, pp. 3–23.

Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009.

Doug Kohlhoff, ‘Did Henry Hacking shoot Pemulwuy?: A reappraisal’, in Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol. 99, no. 1, Jun 2013, pp. 77–93.