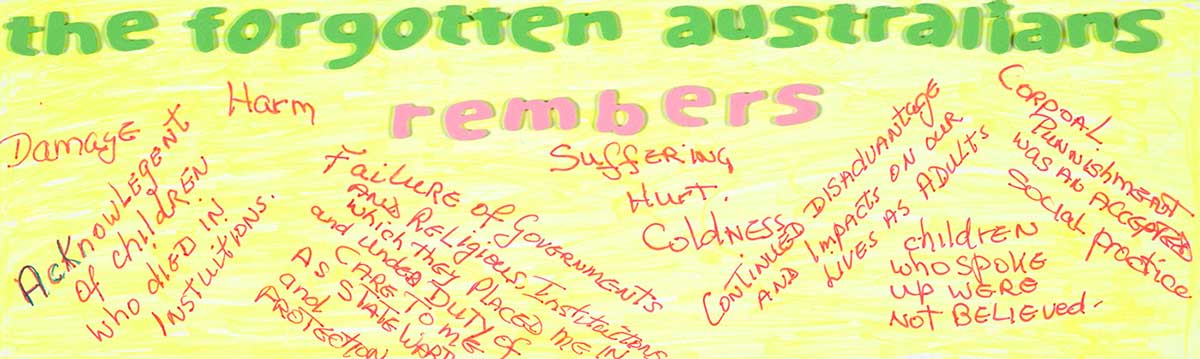

On 16 November 2009 Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a formal apology on behalf of the nation to Australian-born children in care, often known as ‘Forgotten Australians’, and to former child migrants who had been subject to appalling deprivations and abuse while growing up in ‘out-of-home care’ across Australia in the 20th-century.

Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, 2009:

We come together today to deal with an ugly chapter in our nation's history … To say to you, the Forgotten Australians, and those who were sent to our shores as children without your consent, that we are sorry. Sorry – that as children you were taken from your families and placed in institutions where so often you were abused. Sorry – for the physical suffering, the emotional starvation and the cold absence of love, of tenderness, of care. Sorry – for the tragedy, the absolute tragedy, of childhoods lost – childhoods spent instead in austere and authoritarian places … Sorry – for all these injustices to you … who were placed in our care … And let us also resolve this day that this national apology becomes a turning point in our nation’s story. A turning point for shattered lives. A turning point for governments at all levels and of every political hue and colour to do all in our power to never let this happen again. For the protection of children is the sacred duty of us all.

Forgotten Australians

It is estimated that for around 50 years in the early to mid-20th century, around 500,000 Australian-born children were removed from their families and placed in accommodation and welfare institutions, often known as ‘homes’. Reasons for removal included poverty, abuse and the absence of adult guardians.

Not everyone agrees with the term 'Forgotten Australians', with some preferring ‘care leavers’.

Child migrants

These children lived in homes alongside migrant children who had been sent to Australia, mostly from the United Kingdom, but also from Malta. From around 1912 to the late 1960s, approximately 7,000 child migrants were sent to institutions throughout Australia.

Before the Second World War, the rationale was to remove children from overcrowded British welfare institutions and provide them with farming or domestic skills. After the war it was ‘Empire settlement’, which aimed to increase the Australian population through bringing in British-born citizens.

Child migrants were sometimes illegitimate or abandoned children, while others were removed from their parents and families through deception. Almost all came from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Child migrants were usually eight to 13 years of age on their arrival in Australia, although many were younger than this, some as young as three. Child migrants were sent to charitable or welfare institutions across the country, often run by Christian religious orders.

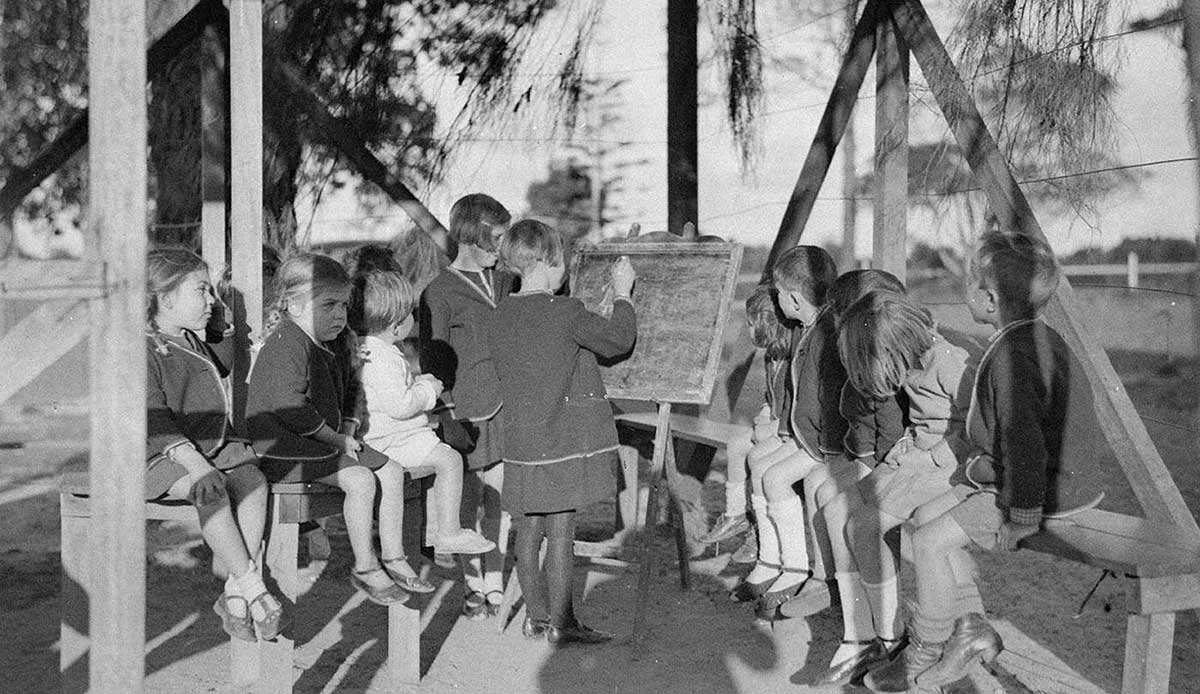

Life in the homes

Institutional life was often difficult and depersonalised. The names of children were changed or substituted with numbers, contact with family was forbidden, personal possessions were banned and events marking the passage of life – such as birthdays – were rarely acknowledged.

Many children recall exploitative and dangerous hard labour, criminal physical, psychological and sexual abuse, neglect and deprivations.

While not all children were abused or suffered neglect, no child was safe from such fates because the system was poorly resourced, the staff lacked appropriate training and government supervision was totally inadequate.

The system was fundamentally unsafe. And often when children complained about their treatment they were not believed, with adults in positions of power simply denying that the victims’ worst experiences ever happened.

Uncovering the history

Many of these institutions closed in the 1970s as increasingly progressive social policy and government programs meant children were placed in smaller, family group homes or foster care arrangements.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, a growing number of complaints about institutional care, and attempts to reunite families, brought about a national discussion. Various support and advocacy groups lobbied for an official inquiry into these institutions, including the Care Leavers Australasia Network, the Alliance for Forgotten Australians and the Child Migrants Trust.

In 2000 then Australian Democrats Senator Andrew Murray, himself a former child migrant who had grown up in Zimbabwe, instigated a Senate inquiry into child migrants, and in 2003 a Senate Inquiry into Children in Institutional Care.

The first inquiry focused on former child migrants who had been brought from Malta and the United Kingdom to Australia and placed in institutional care, and the second on the lives of Australian-born children in out-of-home care.

Two reports were produced: Lost Innocents: Righting the Record – Report on Child Migration (August 2001) and Forgotten Australians: A Report on Australians Who Experienced Institutional or Out-of-home Care as Children (August 2004).

These reports recounted a history of ‘out-of-home care’ in Australia in the 20th century, and should be read alongside Bringing Them Home: National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families (1997). They recommended that the Australian Government issue either a statement of acknowledgement or an apology.

The Lost Innocents recommended that the government issue a formal statement of acknowledgement, sorrow and regret. However, Forgotten Australians advocated ‘a formal statement acknowledging, on behalf of the nation, the hurt and distress suffered by many children in institutional care, particularly the children who were victims of abuse and assault; and apologising for the harm caused to these children’.

Submissions to the inquiries

Both inquiries took evidence from people who had been personally affected. The Lost Innocents committee received 99 confidential submissions and 153 public submissions and the Forgotten Australians committee received 174 confidential submissions and 440 public submissions.

The Forgotten Australians report noted:

1.8 Without doubt this inquiry has generated the largest volume of highly personal, emotive and significant evidence of any Senate inquiry.

1.9 Many hundreds of people opened their lives and the memories of traumatic childhood events for the Committee in their public submissions and at the hearings. Some people were actually telling their story to another person, including family, for the first ever time. For some these memories and their life story remain so distressing that they asked for their name to be withheld or to be identified only by their first name. Many others who for a range of reasons preferred that their identity remain undisclosed provided confidential submissions. All these people desperately wanted the Committee to read and hear what they had experienced in childhood and the impact that those events have had throughout their life. They wanted their voice to be heard.

Both reports recognised there were many people who, for a variety of reasons, did not feel comfortable providing evidence.

One submission in Forgotten Australians expressed this:

By proxy, may [my submission] also convey the feelings and sentiments of the many who through death, ill health, damaged psyche, painful shame or a denial of education are unable to have their say in regards to how they were treated while in these institutions. (Sub 365)

The need for an apology

The 2009 National Apology was a significant moment. It was hoped that it would offer individuals validation by ensuring that their stories were heard and believed, and promote emotional and psychological healing.

There was a practical component to the apology as well, relating to compensation, both in financial terms and in relation to emotional support, family history research services and commemorative memorials.

Moreover, the Australian Government promised to work with the National Library of Australia and the National Museum of Australia to record the legacy of these stories and ‘provide future generations with a solemn reminder of the past. To ensure not only that your experiences are heard, but also that they will never ever be forgotten’.

Explore defining moments

References

Apology to the Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants, 2009

Lost Innocents: Righting the Record – Report on Child Migration

Alan Gill, Orphans of the Empire, Random House, Milsons Point, NSW, 1998.

Nell Musgrove, The Scars Remain: A Long History of Forgotten Australians and Children’s Institutions, Australian Scholarly Publishing, North Melbourne, Vic., 2013.