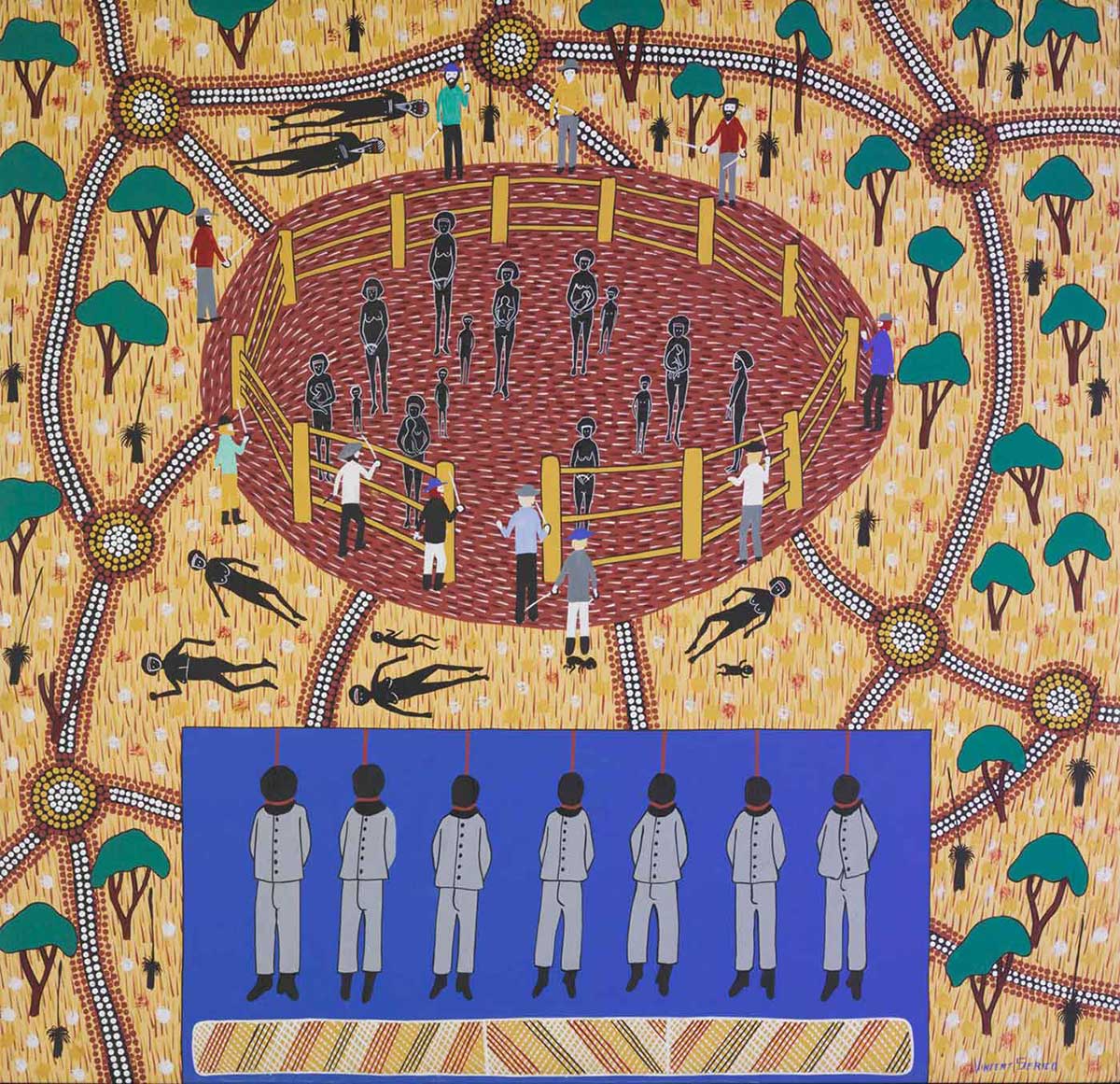

Early in the morning of 18 December 1838, seven men were publicly hanged at the Sydney Gaol. They were the first British subjects to be executed for massacring Aboriginal people.

The Myall Creek massacre was neither the first nor last massacre of Aboriginal people in Australia but the NSW Supreme Court trials that followed set a judicial precedent. However, attitudes towards such massacres took longer to change.

Gamilaraay elder, Uncle Lyall Munro, 2013:

[The Myall Creek massacre Supreme court trials were] the first place white man’s justice done some good. Right across Australia, there were massacres. What makes Myall Creek real is that people were hanged, see. That was the difference.

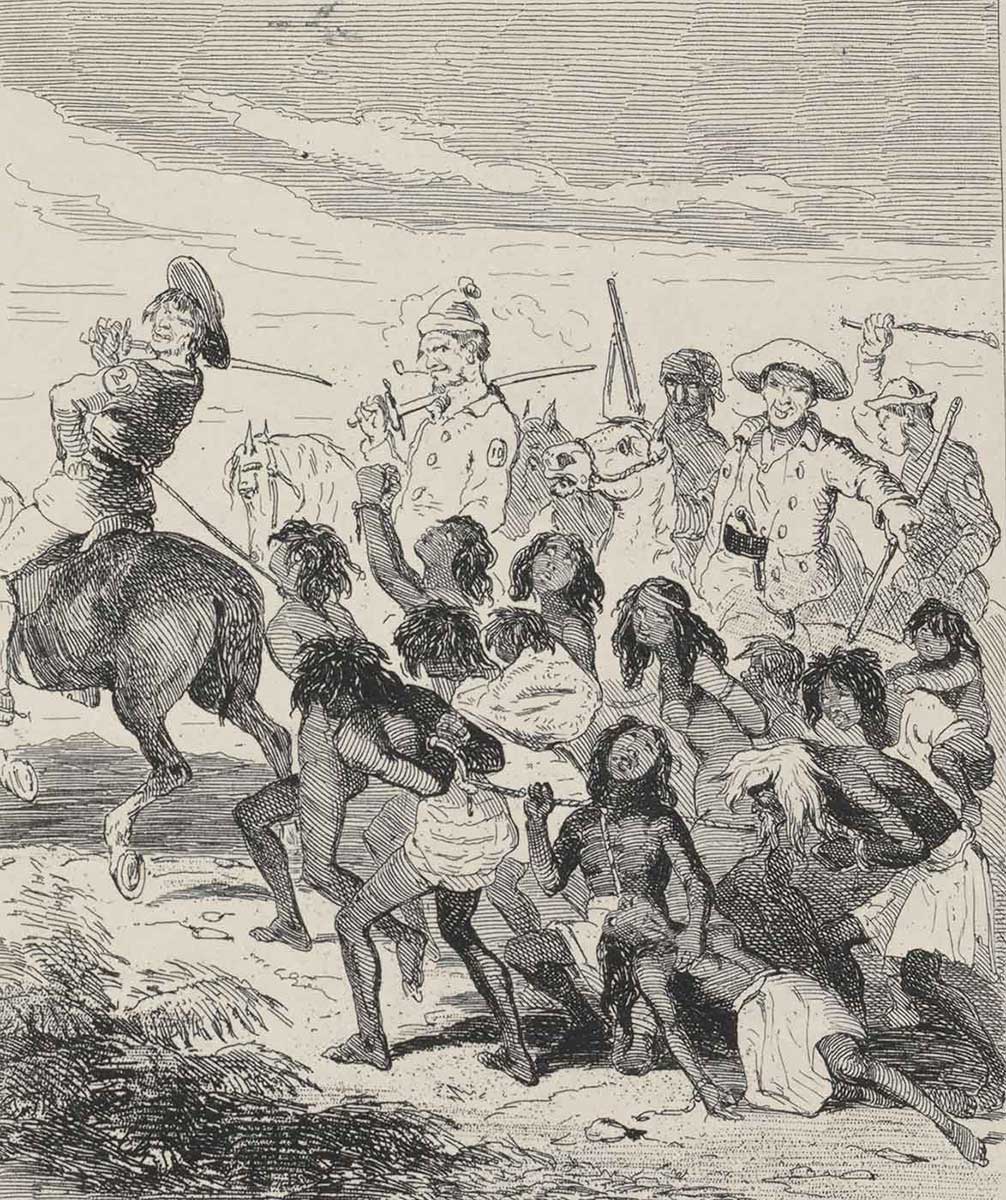

Frontier violence

By the 1830s, frontier violence around NSW had become so widespread that the murder of Aboriginal people by British colonial stockmen, settlers and convicts was generally accepted, despite British law clearly articulating that it was a crime punishable by death.

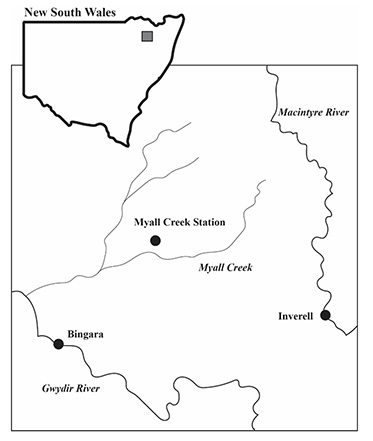

The massacre at Myall Creek was just one of a sequence of violent events that accompanied settler expansion in the Gwydir region of north-eastern NSW in the 19th century.

While it is likely that only a fraction of the violence is recorded in the conventional historical record, it is telling that a contemporary authority and eyewitness, Muswellbrook police magistrate Edward Denny Day, termed this conflict ‘a war of extermination’.

Violent attacks increased in savagery towards the latter part of the decade. The summer of 1837–38 was particularly violent.

Major James Nunn, the Commandant of the New South Wales Mounted Police, had been sent from Sydney to lead a punitive expedition against the Aboriginal people who had killed stockmen in separate incidents of Frontier conflict.

His response, however, was extreme. On 26 January 1838 Nunn and his men massacred up to 50 Aboriginal people camped at Waterloo Creek. They also encouraged nearby stockmen and settlers to murder any Aboriginal person they came across.

Myall Creek

By the mid-1830s conflict had greatly reduced the population of the Wirrayaraay people, a tribal clan of the Gamilaraay nation.

Seeking sanctuary, a group of Wirrayaraay people decided to camp on Henry Dangar’s property at Myall Creek station near present-day Bingara, in May 1838.

A mutually beneficial arrangement evolved whereby the Wirrayaraay people had temporary reprieve from violence while their men assisted various stockmen with their work on nearby stations.

While the Wirrayaraay people were camped on Dangar’s property, the station hands, and particularly the assigned convict stockman Charles Kilmeister, enjoyed friendly relations with them.

The stockmen and the Wirrayaraay people spent time together in the evenings dancing and singing by the campfire. Some of the names that the stockmen gave the Wirrayaraay people have survived in the court depositions: Old Joey, King Sandy, Sandy, Martha, Charley, Heppita, Tommy, and Daddy.

Just before sunset on 10 June 1838, while the Wirrayaraay people were preparing for their evening meal, a group of convicts, former convicts and one settler arrived at the station fully armed. The group tied up the frightened Wirrayaraay people and led them away from their campsite.

Two women and a young girl were set aside, while another young girl was given to Yintiyantin, an Aboriginal stockman whose country was further south and who worked on the Myall Creek station. Two boys escaped by jumping into the creek.

George Anderson, hut keeper at Myall Creek station, later described the terror of the Wirrayaraay people as they were led away and slaughtered. Afterwards, their bodies were piled up and burned. The remains of at least 28 corpses were later observed at the site, but the final death toll has never been confirmed.

Supreme Court trials

Conspiracies of silence usually shrouded massacres of Aboriginal people and perpetrators were rarely punished.

The Supreme Court trials that followed the Myall Creek massacre were therefore exceptional, firstly because of the final outcome (the execution of British subjects), and secondly because of the wealth of information that the court transcripts preserved detailing the events leading up to the massacre and the legal proceedings.

The process of justice was initiated by three individuals who reported the event: station manager William Hobbs, local police superintendent Thomas Foster, and settler Frederick Foot. It was carried out by the new governor Sir George Gipps and the Attorney-General John Plunkett.

Gipps instructed the Muswellbrook police magistrate Edward Denny Day to investigate. On visiting the site and discovering partially burned bone fragments, Day took depositions from 19 witnesses.

These depositions provided the grounds on which Day arrested 11 of the 12 perpetrators and transferred them to the Sydney Gaol for trial. The only free settler among the perpetrators, Hawkesbury-born John Fleming, fled and evaded capture.

First trial

On 15 November 1838 the first trial was held in the NSW Supreme Court before Chief Justice Sir James Dowling and a jury of 12 settlers. The first trial set out to establish that murder had been committed at Myall Creek and that the accused were guilty of this crime.

The prosecution centred around the burned skeletal remains of a very tall Wirrayaraay adult male, identified as ‘Daddy’.

The so-called ‘Black Association’, a group of landowners including Dangar, funded a formidable defence team to represent the accused on trial. The ‘Black Association’ allegedly set out on a program of intimidation and advised jurors to absent themselves from court.

At the conclusion of the trial, none of the witnesses, such as the Myall Creek hut keeper George Anderson, could swear that the remains of the large body was that of the Wirrayaraay Elder, Daddy. Therefore, despite the damning evidence presented, the jury declared all 11 defendants to be not guilty after less than 20 minutes’ deliberation.

However, Attorney-General Plunkett declared dissatisfaction with the verdict and kept the prisoners in gaol pending trial on new charges and using different evidence, this time indicting the prisoners for the murder of a Wirrayaraay child.

The defendants’ counsel had advised his clients to remain silent during the trial, but Plunkett hoped that they would give evidence against each other when divided and so separated them into one group of seven and another of four.

Second trial

Given the high level of negative attention that the first trial received in the press, it became increasingly difficult to assemble a jury that would turn up to court let alone remain impartial.

Indeed, ferocious arguments were taking place throughout the colony as to whether a fair trial could be held at all. On 26 November the trial was postponed to allow the defendants’ counsel to read the new charges, and the following day legal arguments took place as to whether the defendants could be retried.

The second trial officially began on 29 November, yet a large number of men who had been called for jury service failed to turn up. Plunkett asked the judge to fine them harshly. Penalties of up to £10 were issued.

The lack of sufficient jurors led the Court Sheriff to ‘pray a tales’, which meant hauling in any male passer-by in the vicinity of the court. Once a full jury was present, the trial began.

Seven of the defendants were tried by a new judge, William Burton. At the conclusion of the second trial, all of the seven men were found guilty and sentenced to public execution.

Although the four remaining defendants (John Blake, James Lamb, George Palliser and Charles Toulouse) were to be prosecuted at a trial in which Yintayintin would give eyewitness testimony, this never took place – Yintayintin disappeared under mysterious circumstances and the four surviving perpetrators walked free in February 1839.

Aftermath

A British settler, JH Bannatyne, wrote to a friend in England and described the trials, relating how they had ‘created an extraordinary sensation in the Colony and will be the subject of gossip for many a long day yet’.

The colonial community of New South Wales was more outraged by the execution of British citizens than they were by the massacre of the Wirrayaraay people.

The fate of the escaped settler, John Henry Fleming, reveals much about the culture and society of the colony of New South Wales at this time. The obituary of Fleming published in the Windsor and Richmond Gazette in 1894 testifies to the long and rich life that he enjoyed after the massacre.

The privileged status that settlers enjoyed in the colony at this time enabled Fleming to escape, hide and reintegrate into society, despite the atrocities for which he was responsible being so well known and there being a lucrative reward for his capture.

In contrast, William Hobbs, one of the three men who reported the massacre, lost his position with Dangar and had great difficulty finding subsequent employment.

John Blake, one of the four perpetrators who escaped conviction, committed suicide in 1852. It has since been speculated that this reflected the trauma and guilt arising from his involvement in the massacre.

The executions of British subjects for the murder of the Wirrayaraay people hardened colonial attitudes towards the First Peoples of Australia and shaped later behaviours on the Frontier.

In Australian English, the word ‘dispersal’ became the commonplace euphemism used to refer to the killing and massacre of Aboriginal peoples, which went on to take more insidious and devious forms: disease, starvation and the poisoning of food rations are just some of the ways that the Indigenous population was further decimated.

Meanwhile, perpetrators took better steps to cover their tracks and avoid prosecution.

Commemorations

While today it is acknowledged that the First Peoples of Australia have deep connections to their country, the often brutal ways in which they were dispossessed of their homelands during colonisation are not.

One of the most powerful and pervading legacies of 19th- and early 20th-century colonialism in Australia has been the failure to discuss how the British colony was established through Frontier conflict such as the Myall Creek massacre.

The Myall Creek memorial site, which opened in June 2000, is important because it explicitly commemorates a massacre that is an example of this otherwise unspoken conflict.

In this way, the memorial site stands as both a site-specific and a national monument, in that it preserves memory of one particular massacre but is also representative of many more that took place across the country.

The memorial site is also important because it has been set up by Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in acknowledgement of our difficult, shared history.

Every year on the Sunday of the June long weekend, hundreds of people, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, gather at the site to attend an annual memorial service.

Descendants of the victims and survivors, such as Aunty Sue Blacklock, Aunty Elizabeth Connors and Uncle Lyall Munro, as well as descendants of the perpetrators of the massacre, such as Beulah Adams and Des Blake, come together to remember and reflect on past atrocities, as well as to express shared aims for the future.

Gamilaraay elder Sue Blacklock, one of the founders of the memorial site and service, talked about what the annual service and the reconciliation process means to her in a 2013 SBS interview:

It has lifted a burden off my heart and off of my shoulders to know that we can come together in unity, come together and talk in reconciliation to one another and show that it can work, that we can live together and that we can forgive. And it really just makes me feel light. I have found I have no more heaviness on my soul.

Explore Defining Moments

References

First trial, on the Macquarie University website

Myall Creek: A massacre and a reconciliation, SBS

National Heritage Places list entry on the Department of the Environment and Energy website

Second trial, on the Macquarie University website

P Edmonds, ‘“Walking Together” for reconciliation: From the Sydney Harbour Bridge Walk to the Myall Creek Massacre commemorations’ in Settlers Colonialism and (Re)conciliation: Frontier Violence, Affective Performances, and Imaginative Refoundings, 2016, pp 90–125.

Jane Lyndon and Lyndall Ryan, Remembering the Myall Creek Massacre, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2018.

Mark Tedeschi, ‘Justice Evaded, Justice denied’, Part 1, Inside History, May–June, 2014.

Mark Tedeschi, ‘We remember them’, Part 2, Inside History, July–August, 2014.

Michael Pickering, ‘Where are the Stories’, in The Public Historian, vol. 32, no. 1, pp 79–95.