Douglas Mawson is a national hero. He was a remarkable explorer and the expeditions he led helped to establish the Australian Antarctic Territory.

He is also famous for one of the most extraordinary feats of endurance in the history of Antarctic exploration. But Mawson was first and foremost a scientist.

Whereas other explorers were driven by a nationalistic urge to claim territory or beat rivals, Mawson’s expeditions were primarily scientific. Their achievements in geology, cartography, meteorology, geomagnetism and marine biology were groundbreaking.

Geographer Sir Archibald Grenfell Price in The Winning of Australian Antarctica:

Although future generations may continue to afford a high place to the gallant men of several nations who reached the South Pole … they will, I think, pay increasing honour to the man who, of all southern explorers, gave the world the greatest contributions in south polar science and his own people the greatest territorial possessions in the Antarctic.

Australia and Antarctica

Sealing and whaling quickly became important industries to early European colonists. As the number of animals in Australia’s coastal waters were depleted, ships pushed farther and farther south.

This gave rise to an increased scientific interest in Antarctica from the mid-19th century onwards.

The first Australian to set foot on continental Antarctica was young Tasmanian physicist Louis Bernacchi, who landed there in 1899 as part of the Southern Cross expedition, which was the first to over winter on the Southern continent. He concluded that, ‘Antarctic exploration is of capital importance to science’.

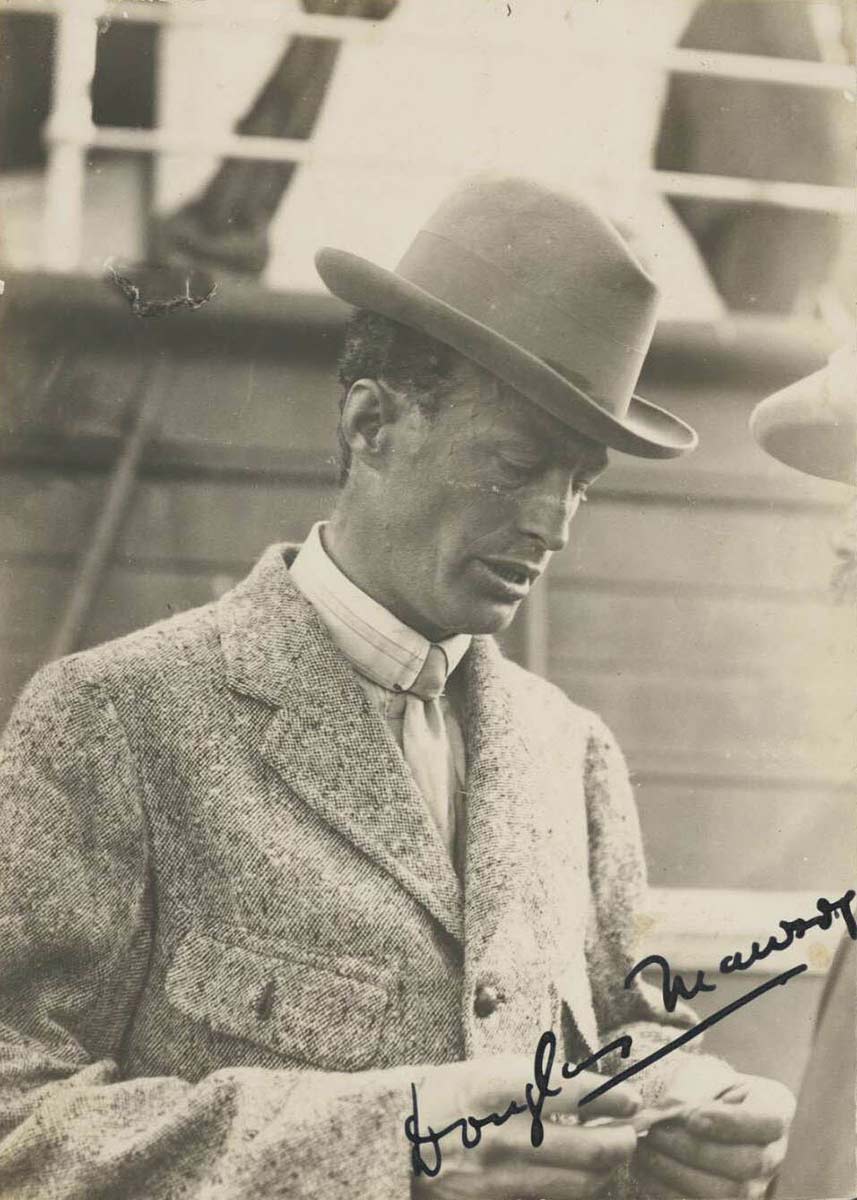

Douglas Mawson

Mawson was born in Yorkshire in 1882 but moved to Sydney with his family when he was two. After studying engineering and geology at university he conducted geological research in Vanuatu and outback Australia.

Mawson and Shackleton

In 1905, he was appointed lecturer in mineralogy and petrology at the University of Adelaide.

Two years later, Mawson met the Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton who was visiting Adelaide on his way south to lead the British Antarctic Expedition (BAE). Shackleton appointed Mawson the expedition’s physicist.

As part of the BAE, Mawson was among six men who made the first ascent of Mount Erebus in March 1908.

The following year he trekked 2,028 kilometres to claim the South Magnetic Pole for ‘the British nation’. It was during this gruelling march that he conceived of his own Antarctic expedition.

Mawson wanted to carry out a detailed examination of more than 3,000 kilometres of the Antarctic coast and its hinterland due south of Australia. This he intended to do in pursuit of scientific data rather than glory, though as a geologist he was also interested in the discovery of any exploitable mineral resources.

Mawson continued to work on his idea for an Antarctic expedition and, while in London in 1910, outlined his plan to Shackleton who suggested they conduct a joint expedition. Shackleton was later forced to withdraw, leaving Mawson to organise and lead what would be an Australian and New Zealand expedition rather than a British one.

Australasian Antarctic Expedition

In his account of the expedition, Home of the Blizzard, Mawson wrote:

For many reasons … I was desirous that the Expedition should be maintained by Australia. It seemed to me that here was an opportunity to prove that the young men of a young country could rise to those traditions which have made the history of British Polar exploration one of triumphant endeavour as well as of tragic sacrifice. And so I was privileged to rally the ‘sons of the younger son’.

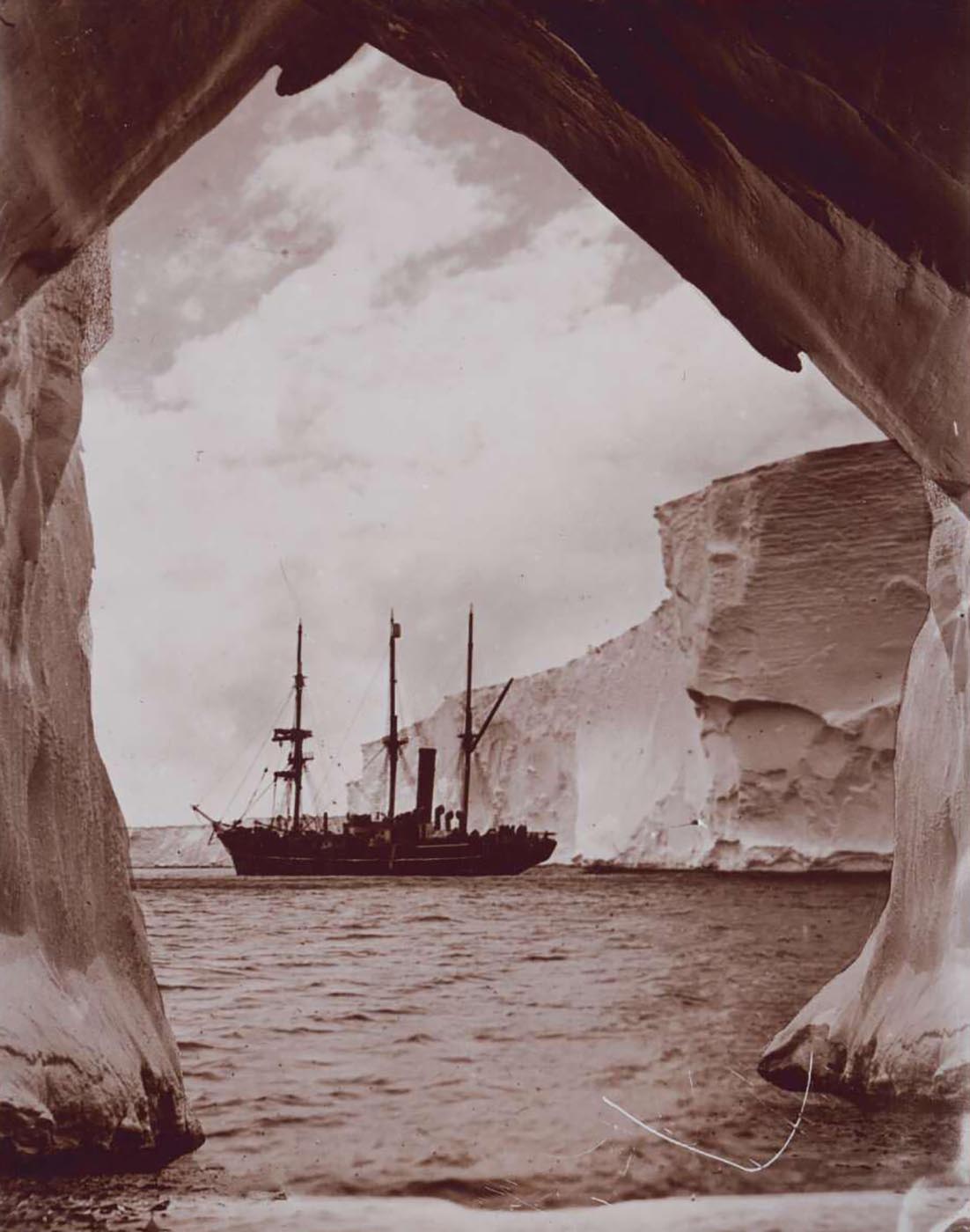

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) sailed from Hobart for Antarctica in the Aurora on 2 December 1911 with a view to returning in early 1913.

Mawson’s plan required the establishment of three bases: a radio relay station at Macquarie Island; a main base at Commonwealth Bay; and another base 2,000 kilometres west on the Shackleton Ice Shelf.

At each base, and in expeditions from them, Mawson and his men would conduct scientific research. Also, an extensive program of marine science was to be carried out from the Aurora under Captain John Davis King.

Mawson wisely ensured that among the AAE’s members was photographer Frank Hurley who has left us stunning images and film footage of the expedition.

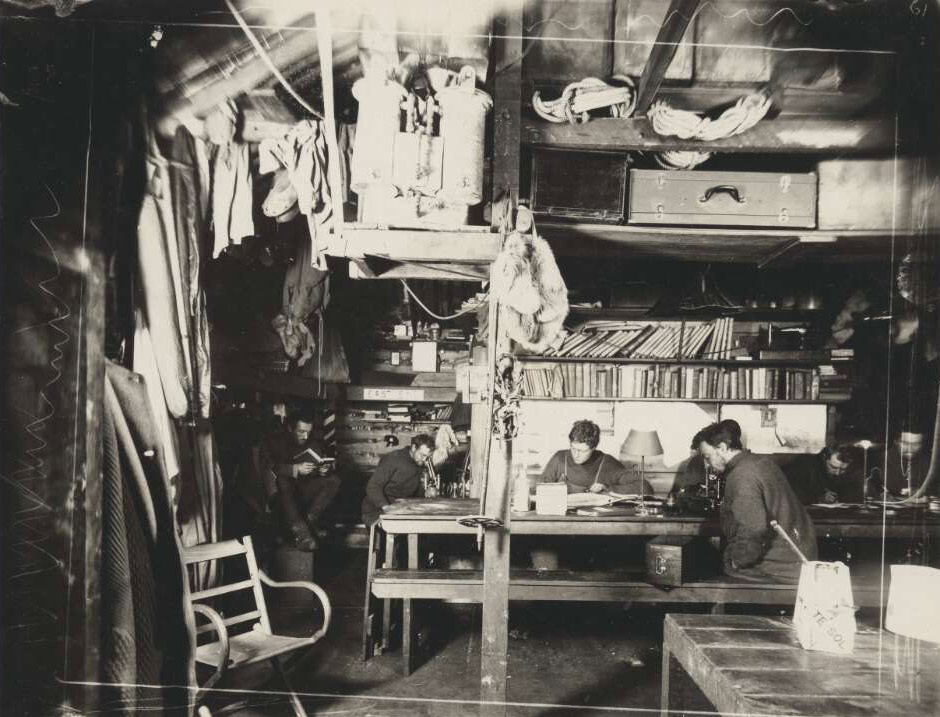

In March 1912 Mawson and his party arrived in Commonwealth Bay, 2,670 kilometres south of Hobart. The 18 men spent the autumn and winter building the Main Base (essentially a hut and small outbuildings) at Cape Denison, conducting research and preparing for land expeditions in the summer.

Mawson, Ninnis and Mertz

Six parties set out from the base in early November on journeys of varying lengths. Mawson’s expedition comprised himself, British Army officer Belgrave Ninnis and Swiss champion skier Xavier Mertz. The three men intended to map the coastline east of Cape Denison – a round trip of 1,500 kilometres.

A month later, 499 kilometres from Cape Denison, Ninnis fell into a crevasse at least 50 metres deep, taking his sledge and most of their supplies and huskies with him.

Peering into the crevasse, Mawson and Mertz could see little trace of Ninnis, and their calls went unanswered. The rope they had with them was not long enough to mount any effective rescue attempt.

Ninnis’s death hit Mertz the hardest. In his journal, he wrote:

We could do nothing, really nothing. We were standing, helplessly, next to a friend’s grave, my best friend of the whole expedition. We read a prayer in Mawson’s prayer book. This was our only consolation, the last honouring we could do for our beloved friend Ninnis.

After nine hours Mawson and Mertz began their return to base with only ten days of food for a journey that would take at least 30. As they retraced their steps they were forced to eat their dogs. Mawson recorded in his journal:

That night we ate George. He was a very poor sample; chiefly sinews with a very undesirable taste. It was a happy relief when the liver appeared which, if little else could be said in its favour, could be easily chewed and digested.

However, both men were unaware that the dogs’ livers contained toxic levels of Vitamin A. It is thought that this contributed to the deterioration of both men, particularly Mertz.

Bowl of chaos

Mertz died on 8 January 1913. In Home of the Blizzard Mawson wrote:

Outside the bowl of chaos was brimming with drift-snow and as I lay in the sleeping-bag beside my dead companion I wondered how, in such conditions, I would manage to break and pitch camp single-handed. There appeared to be little hope of reaching the Hut, still 100 miles away.

Mawson cut his sledge in half and loaded it with the barest minimum of equipment. Everything else he abandoned except the geological specimens he’d collected along with his journal and that of Mertz, having removed the latter’s covers and unused pages.

Nonetheless it took another 30 days to man-haul the sledge to base, his survival only made possible by stumbling across small food depots left by a search party. But he was falling apart physically.

Mawson returns to base

At one point, a blizzard trapped Mawson in an ice cave for a week. On another occasion, he fell into a crevasse and was only saved by the sledge getting stuck in a snowdrift. He managed to climb five metres of rope to safety despite exhaustion, sickness and near starvation.

Mawson knew that the Aurora would have arrived to relieve the base at Commonwealth Bay. His main worry was getting back before the ship was forced to leave in time to pick up the men at the Western Base before the winter pack ice closed in.

His concerns were well founded. Davis had delayed his departure for as long as possible but as Mawson staggered towards the base he was greeted with the demoralising sight of the Aurora sailing off into the distance.

Mawson then glimpsed the six men who had chosen to remain behind in the hope that his party might return.

Forced to spend another 10 bitterly cold winter months at the station, Mawson wrote his account of the expedition while the group as a whole succeeded in keeping sane by continuing their scientific work, establishing intermittent radio contact with the outside world, and publishing a monthly newspaper called the Adelie Blizzard.

The one exception was the radio operator, Sidney Jeffryes, whose symptoms of mental illness grew increasingly alarming. On his return to Australia he was committed to a psychiatric institution.

Expedition legacy

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition was the first major scientific expedition by Australians beyond their shores. It explored some 6,347 kilometres of mainland Antarctica as well as Macquarie Island.

The analysis and report of the scientific data collected during the expedition was so extensive that it filled 22 volumes when it was published in 1947.

As David Killick puts it in the Australian Antarctic Magazine:

In the cause of science, the men of the AAE quietly made breakthroughs in Antarctic geology, biology, meteorology, magnetism and oceanography. The expedition sent sledging parties across 2,600 miles of unknown country and the Aurora sailed 3,000 km of unmapped coastline.

The party used radio successfully for the first time on the continent. The results of their scientific work filled volumes: daily observations of temperature, barometric pressure, humidity, snowfall, wind speed and direction, daily magnetic and tide observations, hard-won against the cold and wind.

They described the geology and plant and animal life of Cape Denison and Frank Hurley produced more than 2,500 magnificent still images and a documentary film.

Mawson after the expedition

Mawson was knighted soon after he returned to Australia and received many other honours throughout his life.

During the First World War, he worked with the British Ministry of Munitions and the Russian Military Commission working on the transport and production of high explosives, poisonous gas, chemicals and petroleum oil products.

After the war, he became Professor of Geology and Mineralogy at Adelaide University. Throughout his career he made major contributions to Australian geology.

In 1929 and 1930 he organised and led joint Australian, British and New Zealand expeditions to the Antarctic. During this period, he claimed 42% of Antarctica as British sovereign territory. In 1936 sovereignty was transferred to Australia, resulting in the creation of the Australian Antarctic Territory.

Mawson’s abhorrence of the indiscriminate seal and penguin slaughter he witnessed on Macquarie Island during his 1930 expedition informed his advice to the Tasmanian Government to declare the island a wildlife sanctuary. He passionately lobbied for the federal government to undertake regular Australian Antarctic expeditions, which continue to this day.

Mawson died in 1958.

Preserving a historic site

Mawson’s Hut and its outbuildings remain largely intact and are of national and international heritage significance. They are among just a handful of complexes surviving from the ‘heroic era’ of Antarctic exploration.

The timber buildings have suffered from the effects of wind, ice and time. However, the Australian Antarctic Division and the Mawson’s Huts Foundation have stabilised the remains in recent years.

In our collection

References

‘Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–14’, Department of the Environment and Energy

David Killick, Australian Antarctic Magazine, Issue 22, 2012

Douglas Mawson, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Douglas Mawson, The Home of the Blizzard: Being the Story of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911–1914, W Heinemann, London, 1915. Available in many subsequent editions, unabridged and abridged.