With the agreement of the Australian Government, Britain tested atomic weapons at three sites on Australian territory: the Montebello Islands off Western Australia, and Emu Field and Maralinga in South Australia.

The testing took place from 1952 to 1963, mostly at Maralinga.

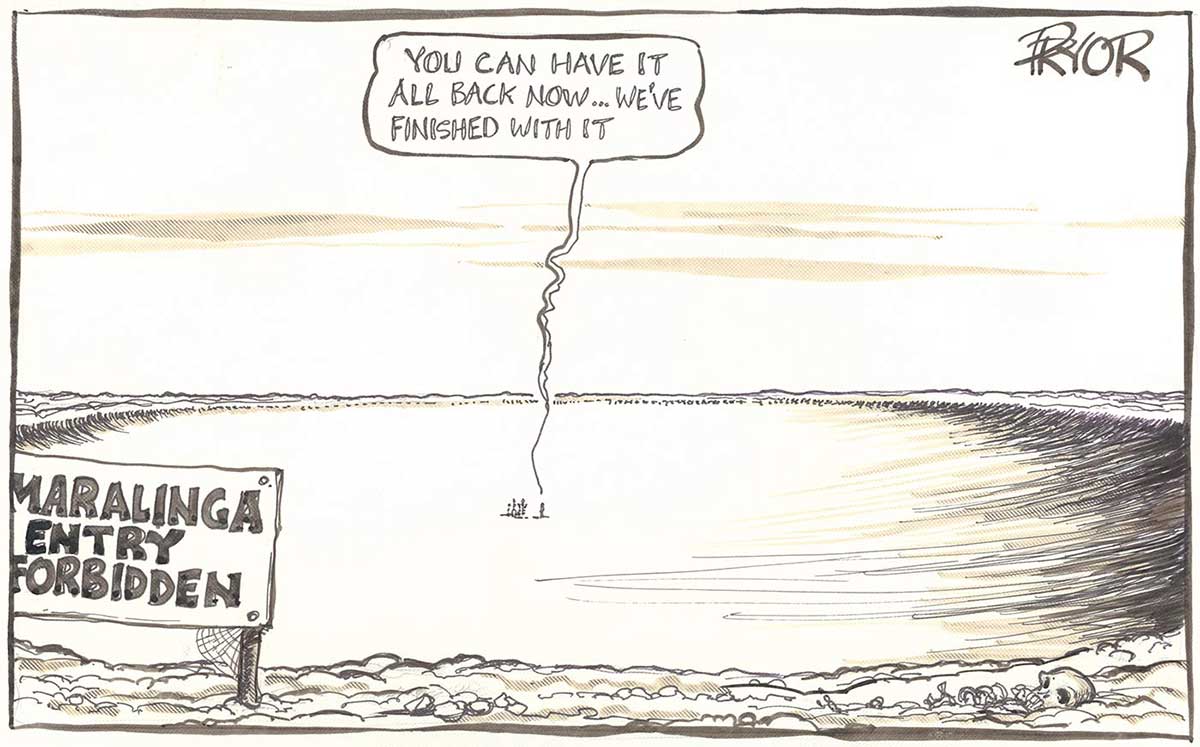

Australian authorities did not discover the extent of the contamination at Maralinga until 1984, just before the land was to be returned to its Aboriginal owners.

Howard Beale, Minister of Supply, 4 May 1955:

The whole project is a striking example of inter-Commonwealth co-operation on the grand scale. England has the bomb and the knowhow; we have the open spaces, much technical skill and great willingness to help the Motherland.

Race to develop nuclear weapons

When the devastating effects of atomic weapons were revealed by the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, the Soviet Union and Great Britain accelerated the development of their own nuclear capabilities.

In 1950 Britain’s Prime Minister Clement Attlee approached his Australian counterpart, Robert Menzies, to seek his agreement to test a British weapon on Australian territory.

Menzies, who was eager to maintain strong links with Britain, agreed.

Nuclear weapons test sites

On 3 October 1952 Britain conducted its first nuclear weapon trial on the Montebello Islands off the Western Australian coast.

Soon after, Britain received Australian Government permission to conduct land-based tests at Emu Field, South Australia. Although two tests were carried out there in October 1953, the remoteness of this site prompted Britain to request a new site at Maralinga, closer to the Trans-Australian Railway.

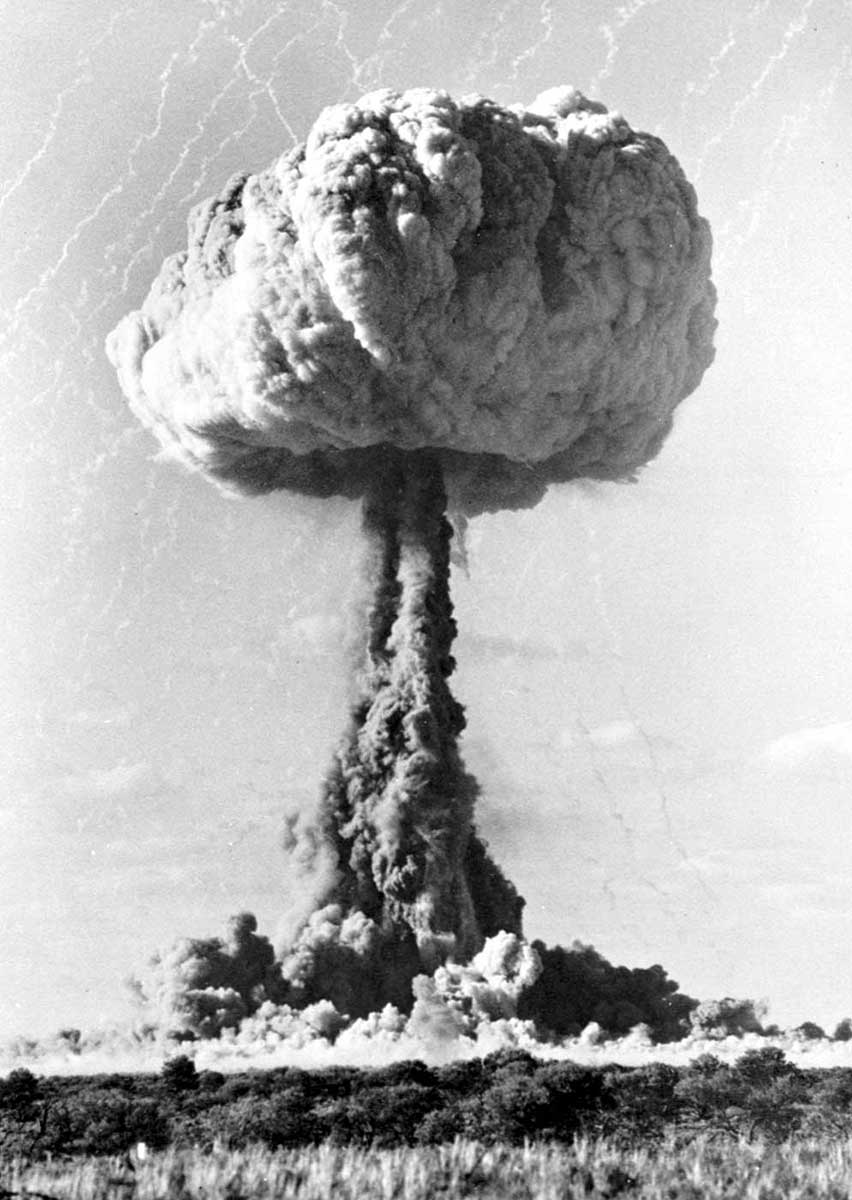

On 27 September 1956 Britain conducted its first test at Maralinga. Britain conducted 12 major trials of nuclear devices across the three sites. Some resulted in mushroom clouds reaching heights of 47,000 feet (14,325 metres), and radioactive fallout blown by wind was detected as far away as Townsville.

Minor trials, major contamination

In addition to major trials, Britain conducted about 200 minor trials over the 10 years to 1963. These were aimed at testing the performance of weapons components and investigating safety issues.

The plutonium contamination at Maralinga was caused by these minor trials, two of which involved burning plutonium and detonating fissile material using conventional high explosives.

As a result just over 22 kilograms of plutonium-239 was dispersed around the site.

Plutonium-239 has a radioactive half-life of more than 24,000 years. This dangerous carcinogen is hazardous to humans if inhaled, ingested or absorbed through breaks in the skin.

Personnel exposed to radiation

Australian personnel took part in every major test.

In earlier tests, RAAF airmen flew through mushroom clouds to conduct sampling without adequate instructions or radiation monitoring devices and, in some instances, without protective clothing.

Air Force and Army servicemen responsible for decontaminating aircraft and transporting equipment were also exposed to radiation.

Impact on Aboriginal people

None of the British tests adequately considered the presence of the Anangu Pitjantjatjara people, especially the greater risk of radiation exposure faced by families living on country.

The extremely limited resources devoted to finding and warning people (one experienced native patrol officer, Walter MacDougall was responsible for covering hundreds of thousands of square kilometres by car) led to incidents of radiation exposure. For example, in 1957, the Milpuddie family was found camping next to a crater left by a Maralinga test detonation.

A letter from Alan Butement, Chief Scientist, Commonwealth Department of Supply, to Walter MacDougall’s manager in 1956 stated, 'Your memorandum discloses a lamentable lack of balance in Mr McDougall's outlook, in that he is apparently placing the affairs of a handful of natives above those of the British Commonwealth of Nations'.

Following the first 'Operation Totem’ test at Emu Field in 1953, Aboriginal people and white pastoralists were exposed to fallout which they described as a ‘Black Mist’.

In addition to radiation danger, Aboriginal people around Maralinga also faced extreme social, emotional and physical hardship from being denied access to food and water resources for more than 30 years.

Clean up and contamination

British nuclear tests were abandoned in 1963 when Britain and Australia signed the United Nations Partial Test Ban treaty.

When Maralinga closed in 1967 British authorities began cleaning up the site. Contaminated debris was buried in trenches topped with concrete. Plutonium-contaminated soil was simply ploughed into the ground.

On the basis of a flawed 1968 British scientific report, the Australian Government agreed that Britain had fulfilled its decontamination obligations.

In May 1984 Australian scientists conducted radiation surveys in preparation for transferring Maralinga to its traditional owners, the Tjarutja. They found that major and widespread plutonium contamination remained.

Royal Commission

The government responded to growing community concern by establishing the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia under Justice James McClelland.

Released in 1985, the Royal Commission report was highly critical of Britain’s treatment of Australia, the compliant attitude of the Australian Government and the management of the Australian body charged with overseeing the program’s safety. It specifically condemned the lack of commitment to ensuring the safety and welfare of indigenous people.

The commission recommended the test sites be remediated to permit unrestricted access by the traditional owners, who should also receive compensation. It also recommended that the cost of decontamination and compensation be borne by the British Government.

Eight years later, in December 1993, Britain agreed to make a £20 million ex gratia payment towards the estimated $101 million cost of cleaning up Maralinga. In 1994 the Australian Government paid $13.5 million to the Indigenous people of Maralinga as compensation for contamination of the land.

Maralinga rehabilitation

Between 1996 and 2000 all but around 120 square kilometres of around 3,200 square kilometres of Maralinga country had been cleaned to a standard considered safe for unrestricted access.

Maralinga was formally returned to the Tjarutja owners in November 2009.

Still counting the costs

Veterans of the nuclear tests and Aboriginal people near the sites suffer higher cancer mortality rates and more cancers than the general population. As a result of ongoing campaigning, veterans have obtained compensation. In 2017 the Australian Government agreed to provide improved health care to both veterans and Indigenous people.

In our collection

Explore defining moments

You may also like

References

Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency

Black Mist Burnt Country exhibition at the National Museum from 25 August to 18 November 2018

Britain’s dirty deeds at Maralinga, New Scientist

L Symonds, Department of Resources and Energy, A History of British Automatic Tests in Australia, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1985.

Elizabeth Tynan, Atomic Thunder: The Maralinga Story, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 2016.