On 3 June 1992 the High Court of Australia recognised that a group of Torres Strait Islanders, led by Eddie Mabo, held ownership of Mer (Murray Island).

In acknowledging the traditional rights of the Meriam people to their land, the court also held that native title existed for all Indigenous people.

This landmark decision gave rise to important native title legislation the following year and rendered terra nullius a legal fiction.

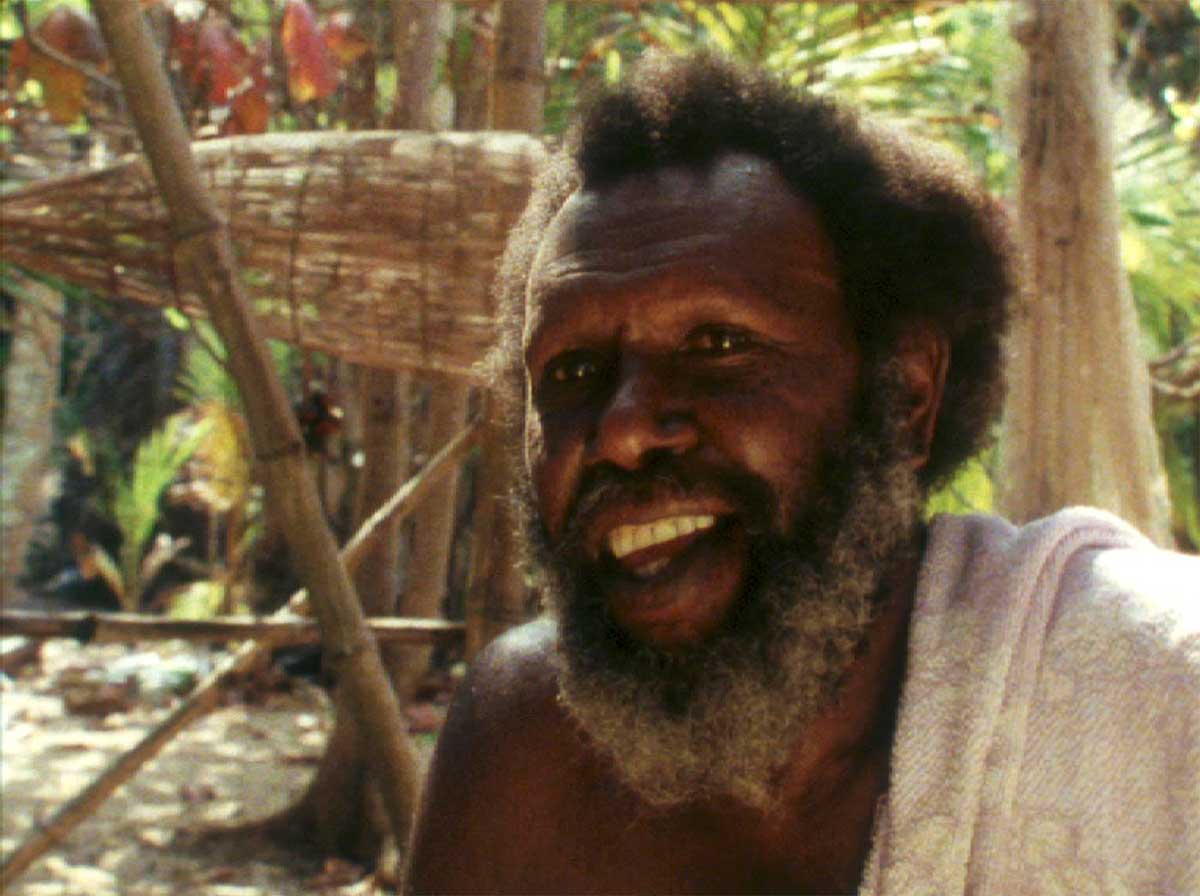

Eddie Koiki Mabo:

My father told me: ‘Son, this land will belong to you when I die.’

In 1770 Lieutenant James Cook claimed ownership of the east coast of Australia on behalf of Great Britain.

This claim was based on the concept of terra nullius, or land of nobody, whereby Britain assumed that Aboriginal people did not have any form of political organisation and therefore no leaders with the authority to sign treaties.

It meant in effect that, according to British law, Australia’s Indigenous population had no legitimate claim to the land on which they had lived for thousands of years.

In 1835 grazier and explorer John Batman used a treaty to buy land around Port Phillip Bay (present-day Melbourne) directly from its Aboriginal inhabitants.

However, Governor Bourke’s Proclamation of 10 October that year stated that people found dwelling on land without the authority of the government would be considered trespassers.

This proclamation quashed the treaty and codified the concept of terra nullius. Aboriginal people therefore could not sell land, nor could individuals acquire it, except directly through the Crown.

Challenging terra nullius

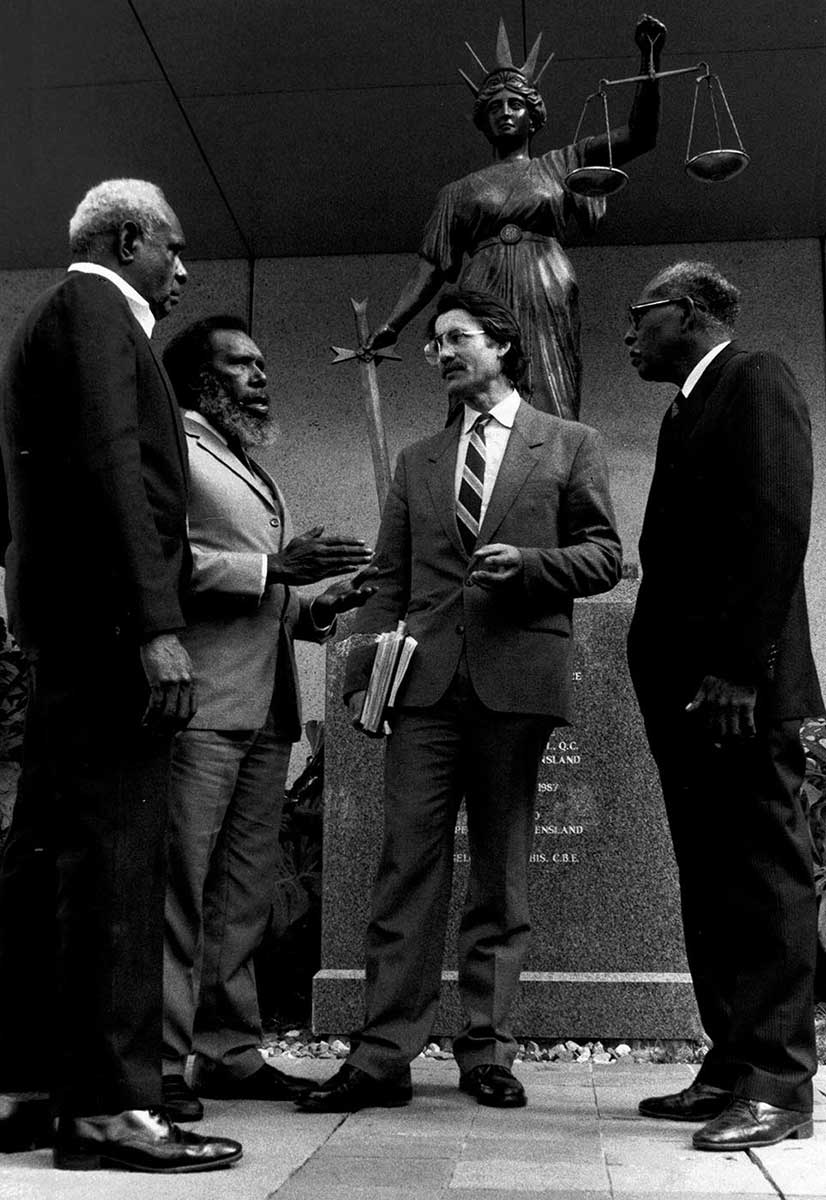

In May 1982 a group of Meriam from the Eastern Torres Strait including David Passi, Sam Passi, Celuia Mapo Salee and James Rice, led by Eddie Koiki Mabo, lodged a case with the High Court of Australia for legal ownership of the island.

Over a period of 10 years, 33 Meriam people, including the plaintiffs, generated 4,000 pages of transcripts of evidence.

The evidence presented included proof that the eight clans of Mer (Murray Island) have occupied clearly defined territories on the island for hundreds of years, and proved the continuity of custom on Mer.

The High Court resolved that the Supreme Court of Queensland should determine the parameters of the case.

While this decision was underway, the Queensland Parliament passed the Torres Strait Islands Coastal Islands Act 1985, which ‘extinguished without compensation’ any Torres Strait Islander claims to their traditional lands.

In February 1986, the Meriam challenged the legislation and in December 1988 the High Court ruled in the Mabo No. 1 case that the Act contravened the Commonwealth Racial Discrimination Act 1975. This enabled the High Court to begin hearing Mabo No. 2, the Meriam’s land rights case.

On 3 June 1992, six of the seven judges agreed that the Meriam held traditional ownership of the lands of Mer. The decision led to the passing of the Native Title Act 1993, providing the framework for all Australian Indigenous people to make claims of native title.

By that time, three of the five plaintiffs – Eddie Mabo, Sam Passi and Celuia Mapo Salee – had died.

Significance of Mabo

The judgements of the High Court of Australia in the Mabo case No. 2 introduced the principle of native title into the Australian legal system. In acknowledging the traditional rights of the Meriam people to their land, the court also held that native title existed for all Indigenous people.

This decision altered the foundation of land law in Australia and rendered terra nullius a legal fiction.

In recognising that Indigenous people in Australia had a prior title to land taken by the Crown since Cook’s declaration of possession in 1770, the court held that this title exists today in any portion of land where it has not legally been extinguished.

The decision proved to be socially divisive. Many politicians and commentators claimed that non-Aboriginal Australians would be in danger of forfeiting the land they legally owned.

But the ruling clearly stated that native title claims only apply to land such as vacant Crown land, national parks and some leased land. Even then it is necessary for Aboriginal claimants to either go to court or a tribunal and prove that they have continually maintained their traditional association with the land in question.

The Mabo judgement also ensures that whenever there is conflict between titles granted by the Crown and the native title, the Crown prevails.

This does not however detract from the huge symbolic importance of the ruling and subsequent legislation, both of which recognise the connection between land, identity and continuity of family and community felt by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

30 May 2012

Mabo 20 years on: a celebration

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Mabo documents, Museum of Australian Democracy

National Film and Sound Archive online resource

Peter Butt, Robert Eagleson and Patricia Lane, Mabo, Wik and Native Title, Federation Press, Leichhardt, 2001.

Peter Russell, Recognizing Aboriginal Title: The Mabo Case and Indigenous Resistance to English-Settler Colonialism, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2006.

Nonie Sharp, No Ordinary Judgment: Mabo, the Murray Islanders’ Land Case, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 1996.