The German explorer Ludwig Leichhardt is remembered for three extraordinary expeditions.

In 1844 Leichhardt and his companions travelled nearly 5,000 kilometres from the Darling Downs in south-east Queensland to Port Essington near what is now Darwin.

The second was a failed attempt in 1846 to reach Perth from the Darling Downs.

In 1848 Leichhardt again attempted the same expedition but this time he and his companions were never seen again.

Their disappearance has been one of the enduring mysteries of Australian exploration.

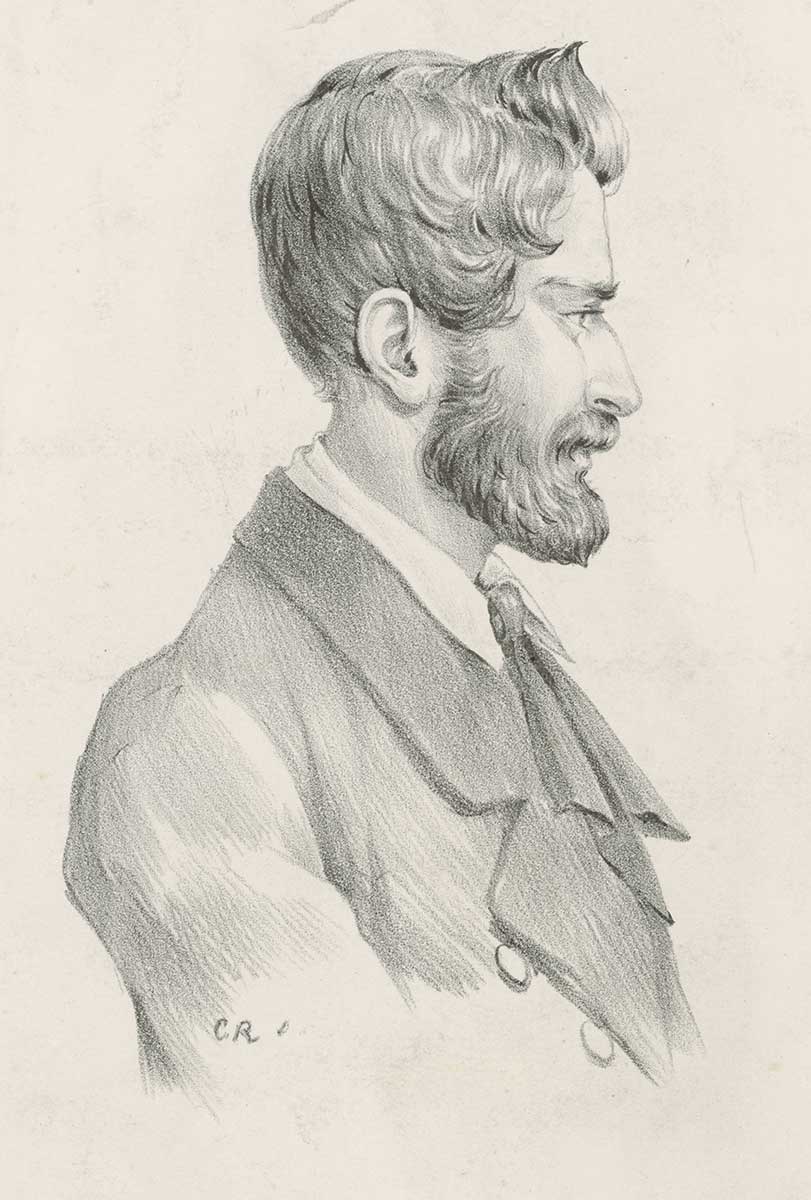

Ludwig Leichhardt, London, 1841:

The interior, the heart of this dark continent is my goal, and I shall never relinquish the quest for it until I get there.

Ludwig Leichhardt

Leichhardt was born in Trebatsch, Prussia in October 1813. He studied languages and science at the universities of Berlin and Gottingen.

At an early age Leichhardt became fascinated with the great Prussian adventurer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt whose writings on his explorations in Latin America at the turn of the 19th century inspired generations of young Germans.

Along with William Nicholson, an English friend he’d met at University in Berlin, Leichhardt studied further in Britain and France and undertook scientific field studies there and in Italy and Switzerland.

Leichhardt recognised that the Australian interior, which had been barely explored by Europeans, represented an enormous opportunity for anyone interested in natural science.

Leichhardt was financially dependent on Nicholson, who paid for his passage and lent him £200, having already supported his friend through much of his university career and independent study.

Leichhardt in Australia

Leichhardt arrived in Sydney on 14 February 1842. By September of that year he was making field expeditions in the Hunter region, studying the geology, flora and fauna, and observing methods of farming and viticulture. He returned to Sydney with collections of rock and plant specimens.

He then travelled alone from Newcastle to Moreton Bay (now Brisbane), collecting specimens. Through these travels and collections he was hopeful of receiving a government appointment, such as director of the Botanic Gardens, or work at the Australia Museum. Unfortunately he never received one.

Though he was never awarded a degree Leichhardt was very well educated and was referred to as Dr Leichhardt on the strength of his medical studies.

First expedition

Leichhardt hoped to join a government-sponsored expedition from Moreton Bay to Port Essington (north of what is now Darwin) to be led by Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell. When this expedition fell through, Leichhardt mounted one himself.

Leichhardt left Sydney in August 1844 and set out from the Darling Downs on 1 October accompanied by nine volunteers, including two Aboriginal guides. He headed north-west to the Gulf of Carpentaria then tracked the coast of the Northern Territory, noting the plants, animals and geology as he went.

The expedition used horses and bullocks to transport their supplies. When they ran out of food they were forced to live off the land, adopting the behaviour of local Aboriginal people whose local knowledge Leichhardt greatly respected.

Though the going was hard, the expedition was largely uneventful except when one of their number, John Gilbert, was killed on 28 June 1845 by Aboriginal men who attacked their camp.

Leichhardt reached the small military outpost of Port Essington on 17 December 1845, having covered 4827 kilometres. ‘I was deeply affected in finding myself again in civilized society, and could scarcely speak,’ Leichhardt wrote.

Long given up for dead, Leichhardt and his companions were feted as heroes on their return to Sydney.

Leichhardt’s journey provided a huge amount of information about the area he’d explored and, having carefully mapped the route of the expedition, blazed the trail for the expansion of European settlement into central Queensland and northern Australia.

Second expedition

Leichhardt’s next major expedition was to cross the continent from the Darling Downs to the Swan River settlement (what is now Perth). It was by far the most ambitious inland expedition ever mounted by Europeans in Australia.

Leichhardt and his party departed in December 1846 with horses, mules, 40 bullocks, 108 sheep and 270 Tibetan goats.

Leichhardt knew Central Australia contained harsh and unforgiving deserts so he planned to skirt their northern limits, travelling across the Top End and arriving on the northern coast of western Australia, then proceeding south to the Swan River.

Conditions had been dry on the first expedition, but this time it rained virtually non-stop. Most of Leichhardt’s companions were struck down by fever. Their animals became frequently bogged in the wet conditions and ultimately wandered off as everyone was too sick to tend them. The tents fell apart and the men were constantly bitten by aggressive paper-nest wasps.

After 800 kilometres they were forced to return to the Darling Downs in June 1847.

Third expedition

Undeterred, Leichhardt tried to cross from the Darling Downs to Swan River the following year. The starting point for Leichhardt and his party of seven was Cogoon Station, the most westerly property on the Darling Downs.

The last Europeans to see the expedition were Allan Macpherson – owner of Cogoon – and two of his workers at a waterhole west of the station.

One of the workers, a shepherd, asked Leichhardt where he was going. Leichhardt replied: ‘To the setting sun.' It was 3 April 1848. Leichhardt and his companions were never heard from again.

In the years after the disappearance several attempts were mounted to try and find the expedition, and although some signs were discovered (the letter 'L' marked on trees, and possible camp sites), no verifiable evidence of what had happened to the group was ever found.

Discovery

The discovery in 1900 of a brass name plate on the border between Western Australia and the Northern Territory suggests that the expedition travelled at least that far.

Well into the 20th century further attempts were made to find relics or explain the fate of Leichhardt and his companions and the Leichhardt mystery continues to attract attention.

Leichhardt’s legacy

Leichhardt’s Australian inland journeys of exploration were the longest of any European at the time.

Geologists and botanists valued Leichhardt’s natural history collections, which he sent to Europe, and the records of his observations which, in an age accustomed to extravagant travellers’ tales, were remarkable for their restraint and accuracy.

Leichhardt left records of his observations in Australia in diaries, letters, notebooks, sketch-books, maps, and in his published works, including an account of his first expedition.

In April 1847 the Geographical Society, Paris, divided the annual prize for the most important geographic discovery between Leichhardt and the explorer and geologist Rochet d'Héricourt who had explored Abyssinia.

On 24 May 1847 the Royal Geographical Society, London, awarded Leichhardt its Patron’s Medal in recognition of ‘the increased knowledge of the great continent of Australia’ gained by his first expedition.

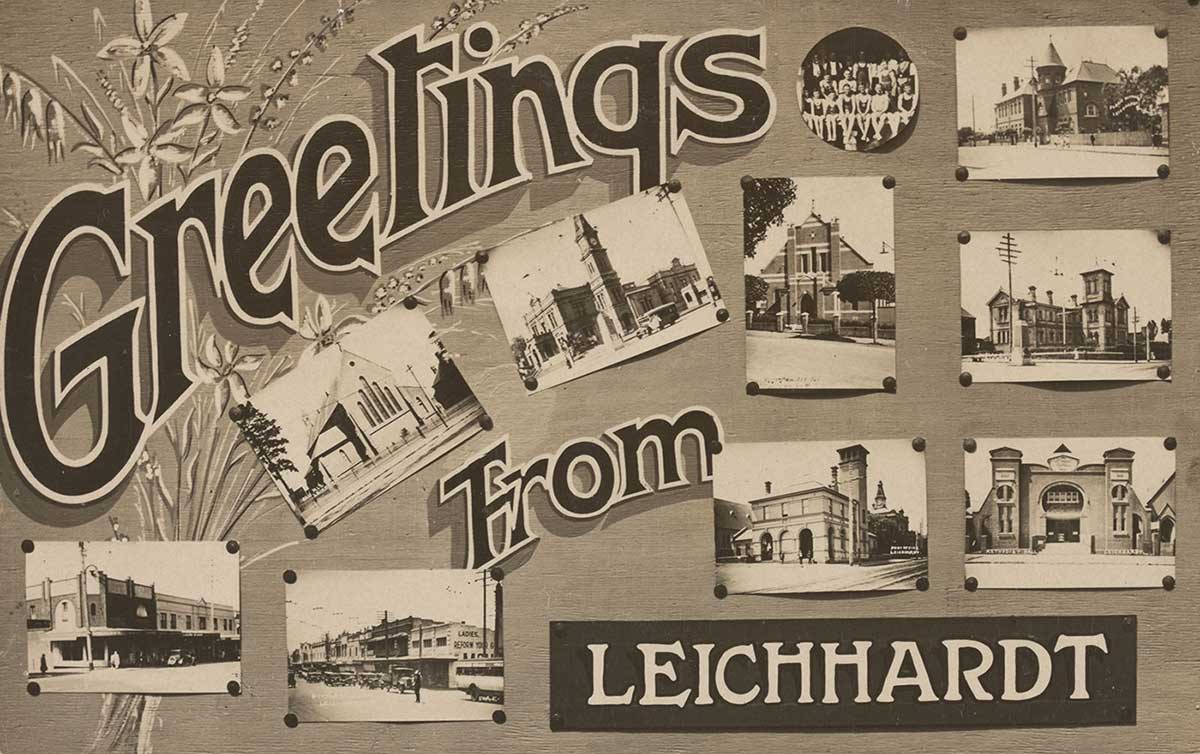

Two suburbs – one in Ipswich, Queensland, the other in inner western Sydney – and a highway in Queensland are named after him.

Ludwig Leichhardt series 15 Jun 2007

He nearly made it: Leichhardt’s ‘grand plan’ of 1848

In our collection

References

Ludwig Leichhardt, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Leichhardt as scientist and diarist

John Bailey, Into the Unknown: The Tormented Life and Expeditions of Ludwig Leichhardt, Macmillan, Sydney, 2011.