The three-year war on the Korean peninsula was the first open conflict of the Cold War.

Australia was one of 21 countries that supported South Korea against an invasion by communist North Korea.

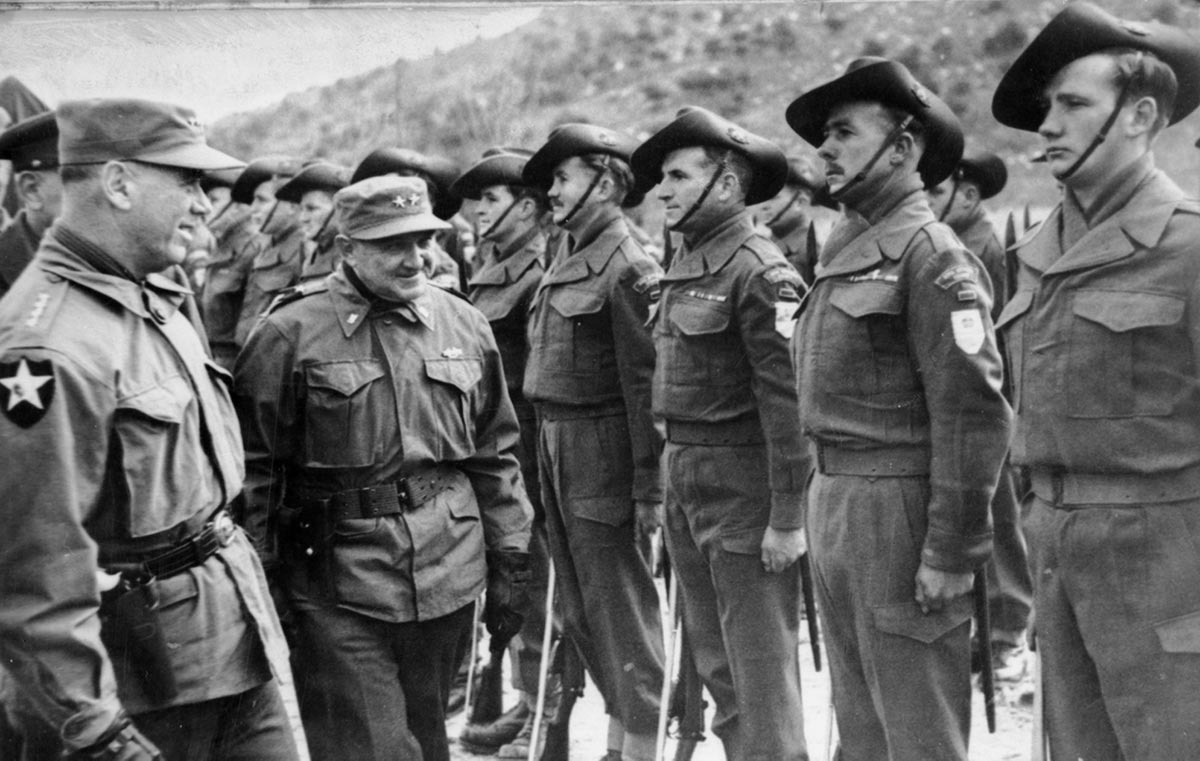

Nearly 18,000 Australian servicemen fought but they returned to an Australian public indifferent to a distant war that had ended in a difficult stalemate.

Sergeant Bill Collings, Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF):

No-one knew I was home from Korea. ‘What are those medals for?’ – they just didn’t have a clue, really.

Causes of the Korean War

Between 1876 and 1910, through a combination of political pressure and military force Japan occupied the Korean peninsula. This began 35 years of sometimes brutal Japanese rule in Korea which ended with Japan’s defeat in the Second World War.

From 1945 the country was divided into zones of occupation by the victorious American and Soviet Union armies. Various Korean groups from far right nationalists to communists claimed to speak for an independent government, but none could reach an agreement with the Soviet and American occupying forces.

In 1948 two separate governments, a communist one in the north and a republican one in the south, were formed each claiming control of the entire peninsula. Animosity between the two parties was high and a border was established along the 38th parallel.

In July 1949, with the Cold War between the west and the Soviet Union intensifying around the globe and Korea considered a low priority, the US withdrew most of its troops from the south. Russia withdrew its troops from the north around the same time.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union-backed North Korean leader Kim Il Sung, made plans to invade the south and unify the country by force.

On 25 June 1950 North Korean troops crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea. Two days later, with the Russian delegate absent and unable to veto any resolution, the United Nations Security Council in New York committed forces from willing nations to the aid of South Korea. These forces were led by the US.

United States involvement

When the North Koreans invaded, the South Korean army collapsed under the onslaught.

The US troops hastily flown in from Japan, where they were serving as an army of occupation, provided support to the South Koreans but were driven back to the southern city of Pusan. There they formed a perimeter around the city and struggled to hold on against repeated North Korean attacks.

After six weeks the UN coalition’s Supreme Commander, General Douglas MacArthur, mounted a successful amphibious landing 330 kilometres north at Inchon, just west of Seoul and very near the 38th parallel. This made it possible to retake the capital and drive back the North Koreans across the border.

However, MacArthur, supported by Washington, made the grave error of trying to take the whole of North Korea. Despite warnings from Peking, he pushed to within 50 kilometres of the Chinese border. It was then, in October 1950, that the Chinese committed huge numbers of troops to support the beleaguered North Koreans.

Again, the UN forces were forced to retreat. They were driven back beyond the 38th parallel and lost Seoul. In March 1951 a fresh UN offensive retook the capital but was held back again near the old border. There both armies remained for the next two years and the war settled into a trench warfare conflict.

After protracted negotiations, mostly over the exchange of prisoners, an armistice was signed that came into effect on 27 July 1953. The war ended with the border between North and South Korea more or less where it was before 1950.

Australia and the Korean War

Prime Minister Robert Menzies, though fervently anti-Communist, was not in favour of sending forces to the Korean War. However, his External Affairs Minister Sir Percy Spender recognised the importance of forging a closer relationship with the US.

Within days of the North Korean invasion in June 1950, Spender pressured the acting Prime Minister Arthur Fadden to commit Australia to the war while Menzies was overseas.

Spender realised that Britain was about to announce it would send ground forces to Korea. He judged that if the British became militarily engaged, Menzies would eventually follow suit, but Canberra would gain more credit in Washington if it made the commitment first.

Menzies, when presented with the fait accompli of Australian military action in Korea publicly proclaimed his support. Within Australia there was very little political or community opposition to involvement in the Korean War. At the time there was strong anti-communist feeling in Australia as shown by Petrov affair and the Australian Labor Party split.

First to be sent to South Korea was the RAAF’s 77 Squadron along with the frigate HMAS Shoalhaven and the destroyer HMAS Bataan – all of which were stationed in Japan at the time.

The Korean War was primarily a land war. In September 1950 the government sent the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR), followed by 1 RAR and 2 RAR. Australia did not introduce conscription for the Korean War even though this commitment required almost all of Australia’s regular infantry troops.

The Australian military served with distinction during the war. At the Battle of Kapyong an Australian battalion (approximately 800 soldiers) along with another from Canada defeated an entire Chinese division (approximately 15,000 men) and prevented it from taking Seoul. Both battalions were awarded US Presidential Unit Citations.

Nearly 18,000 Australian soldiers, sailors, airmen and nurses served in the war.

Forgotten war

It is not known exactly how many people died in the Korean War, but an estimated four million Korean and Chinese people died. More than half were Korean civilians.

About 37,000 UN troops were killed; 339 Australians died and 1216 were wounded.

Australian servicemen and women returning from Korea were largely greeted with indifference. The Australian public was unsupportive of a war that had become mired in stalemate with an enemy that posed no direct threat to Australia.ß

Legacy of the Korean War

Though the Korean and Vietnam wars were both direct conflicts with communism, the Korean War differs from the Vietnamese in that it did prevent the communist north’s conquest of the south.

The newly formed UN passed this test of its effectiveness, but only just. It was the first conflict of the Cold War, and one that could have escalated into a nuclear conflict.

It also fulfilled Sir Percy Spender’s intention of binding Australia more closely to the United States and this resulted in the ANZUS treaty of 1951.

Explore defining moments

References

Department of Veterans’ Affairs

Ben Evans, Out in the Cold: Australia’s Involvement in the Korean War 1950–53, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Canberra, 2013.

Stephen Lewis, Korea: The Undeclared War, Royal Australian Regiment Association, Adelaide, 2008.

Max Hastings, The Korean War, Michael Joseph Ltd, London, 1987.