The cane toad is one of Australia’s best-known introduced pests.

Released in Queensland to help the cane industry deal with insect attacks on sugar cane roots, it has since spread southwards and across the north west of Australia.

As predators have been unable to effectively control their population, the introduction of the cane toad has had a serious impact on the ecosystems of northern Australia.

Walter Froggatt, ‘The introduction of the great Mexican toad Bufo marinus into Australia’, The Australian Naturalist, vol. 9, 1936:

This great toad, immune from enemies, omnivorous in its habits, and breeding all the year round, may become as great a pest as the rabbit or cactus.

Sugar cane farming in Australia

The First Fleet brought sugar cane to Australia. There were repeated small-scale attempts to grow it throughout the early part of the 19th century. Some of these attempts were successful enough to encourage repeated attempts further north.

The person who is widely regarded as the father of the sugar industry, Captain Louis Hope, raised a viable crop at his property in Moreton Bay, Queensland, in 1862. He followed this success two years later by establishing a sugar mill.

From then the sugar industry grew as it followed the colonisation frontier, reaching the far north in the 1880s.

Establishing the industry was not easy. Drought, a common problem in Australian agriculture, affected crops periodically.

However, the biggest problem was the larvae of native beetles, which ate the roots of the sugar cane. These became collectively known as cane beetles, and it would take decades for scientists to determine precisely which beetles were the problem.

Lobbying by cane farmers led to the establishment in 1900 of the Bureau of Sugar Experiment Stations, staffed by entomologists who worked on the cane beetle problem for many years before the introduction of the toad.

Introduction of cane toads

With limited staff and budgets, Bureau of Sugar Experiment Stations staff did the best they could with experiments on different chemical methods of control.

Historian Peter Griggs has speculated that scientists’ success in controlling prickly pear with biological rather than chemical means may have led to a decision by the Bureau to try the cane toad (Bufo marinus).

In 1932 Bureau of Sugar Experiment Stations plant pathologist Arthur Bell attended a conference in Puerto Rico where he learned of and then reported on the apparent success of the American toad, Bufo marinus, in reducing populations of cane beetles.

Three years later, in June 1935, Bureau entomologist Reginald Mungomery travelled to Hawaii where the toads had been introduced from Puerto Rico. He captured a breeding sample and returned to Gordonvale near Cairns, where a special enclosure had been prepared for them.

By August 1935, the toads had successfully reproduced in captivity and 2,400 were released in the Gordonvale area. Remarkably, no studies of the potential impact on the environment had been carried out. Nor had the Bureau of Sugar Experiment Stations even determined whether the toad would actually eat the cane beetles.

Walter Froggatt, a prominent entomologist, was rightly concerned that the toads would become a significant pest. He successfully prevailed on the federal Health Department to ban further releases of the toad.

However, in 1936 Prime Minister Joseph Lyons succumbed to pressure from the Queensland Government and the media to rescind the ban.

Impact of cane toads

While the cane toads thrived in the wild, they had no appreciable impact on cane beetles, which are today controlled by chemical pesticides.

The toad was first declared a problem species in 1950. The poison they exude can kill many native predators whose populations have since declined. They are also indiscriminate feeders, and out-compete native species.

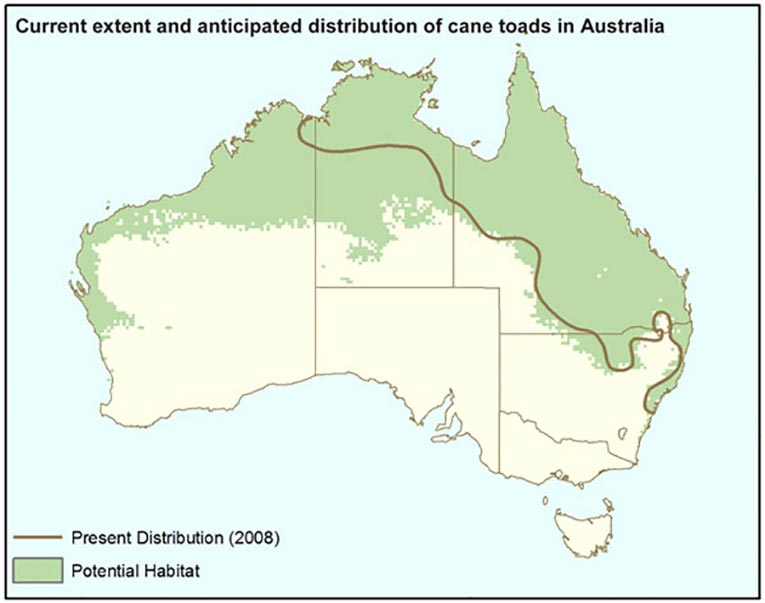

Cane toads have spread well beyond Queensland into coastal New South Wales, the Northern Territory’s Top End and the Kimberley region of Western Australia. They are now moving westward at an estimated 40 to 60 km per year.

In 2010 the Australian Government stated, ‘There is unlikely to ever be a broadscale method available to control cane toads across Australia’.1 While there are predators that can tolerate cane toad poison (for example wolf spiders and estuarine crocodiles) and the water rat cleverly avoids eating the toxic parts of the toad, their efforts alone will not stop the spread of cane toads.

Research efforts are focused on finding methods to protect the most vulnerable native species, reducing the population at the tadpole stage2, and on gaining a better understanding of how other species are adapting to the toad’s presence.

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Cane Toads in Oz by Rick Shine

Introducing the cane toad by Luke Keogh, Queensland Historical Atlas

Walter Froggatt, ‘The introduction of the great Mexican toad Bufo marinus into Australia’, The Australian Naturalist, vol. 9, 1936.