The Indonesian Confrontation, or ‘Konfrontasi’, was a three-year conflict on the island of Borneo and the Malay Peninsula, with Australian troops involved as part of a Commonwealth force under British command.

The conflict centred on whether the former British colonies of Sabah and Sarawak, which bordered Indonesia’s provinces on Borneo, would become part of Indonesia or of recently federated Malaysia.

It was the last time Australia provided military assistance to a largely British conflict. Twenty-three Australian soldiers were killed during the Confrontation, seven of them on operations, and eight were wounded.

General Sir William Jackson, British historian:

[Indonesian Foreign Minister Subandrio] did not spell out what was meant by ‘confrontation’, but it was assumed to be a blending of political, economic and military pressures just short of war.

Emergence of Malaysia

In 1957 Britain granted independence to Malaya. At the time, the nearby island of Borneo was divided between the Indonesian Kalimantan provinces and the relatively small British colonies of Sarawak, Brunei and North Borneo. The three colonies formed the north-western third of the island, which is the size of South Australia. The island is mountainous and covered by thick jungle.

By the early 1960s, Britain was preparing to grant independence to Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo. Malayan Prime Minister Tunkul Abdul Rahman proposed that they join with Malaya to become the federated nation of Malaysia.

Britain supported this move because the Malayan government was pro-British while the expansionist Indonesian government had links to communism.

President Sukarno

Indonesia had gained its independence from the Netherlands in 1945. Sukarno, the country’s first president, bound his new and disparate nation together partly through his fervent nationalism. He was fiercely opposed to the proposed Malayan federation because it interfered with his plans to expand Indonesian territory.

In December 1962 Sukarno’s government backed an attempted coup in Brunei. Though it was quickly put down by British troops based in Malaya, it signalled the start of hostilities.

Confrontation

In January 1963 Dr Subandrio, the Indonesian Foreign Minister, first publicly used the term ‘Konfrontasi’ (confrontation) to describe his country’s policy towards Malaya.

It was a carefully crafted description that allowed Indonesia – which did not want a full-scale conflict with Britain – to stop short of actually declaring war.

Soon afterwards, Indonesia began sending insurgents across the border from Kalimantan to raid towns, police stations and army bases in North Borneo and Sarawak.

British forces based in Malaya were immediately sent to Borneo to protect the 1450-kilometre-long frontier.

Britain granted independence to Sarawak and North Borneo (renamed Sabah) in mid-1963.

A United Nations survey found support among the people of Sabah and Sarawak for federation, and on 16 September 1963 they joined Malaya and Singapore to create Malaysia.[1]

Australia commits

Britain and Malaysia asked Australia to commit troops to the Konfrontasi but the Menzies government was reluctant to antagonise Indonesia. This was partly because Australia shared a long and difficult to defend border with Indonesia on New Guinea [2], but also because its foreign policy was not oriented towards South-East Asia.

However, Australia did provide training and supplies to Malaysian troops, along with two small naval vessels to patrol the area. It had a battalion of 600–800 troops stationed in Malaya, but the Australian Government only agreed for it to be used should Indonesia attack the Malay Peninsula.

Indonesia did just that in September and October of 1964. With Australian assistance, the Indonesian assaults were easily fought off by British and Malaysian troops, but it suggested to Australia that the conflict could escalate further and destabilise the region.

As Britain brought in substantial reinforcements, Australia committed to sending ground troops to Borneo.

At the height of the three-year conflict, British Major General George Lea had 17,000 Commonwealth troops under his command. Most of these were British, including several British army Gurkha regiments from Nepal, along with Australian, New Zealand and Malaysian troops.

Australia sent infantry, artillery, signallers and engineers, as well as squadrons of the Special Air Service Regiment (SAS). Ships of the Royal Australian Navy served in the surrounding waters, and several Royal Australian Air Force squadrons took part during the Confrontation.

Claret operations

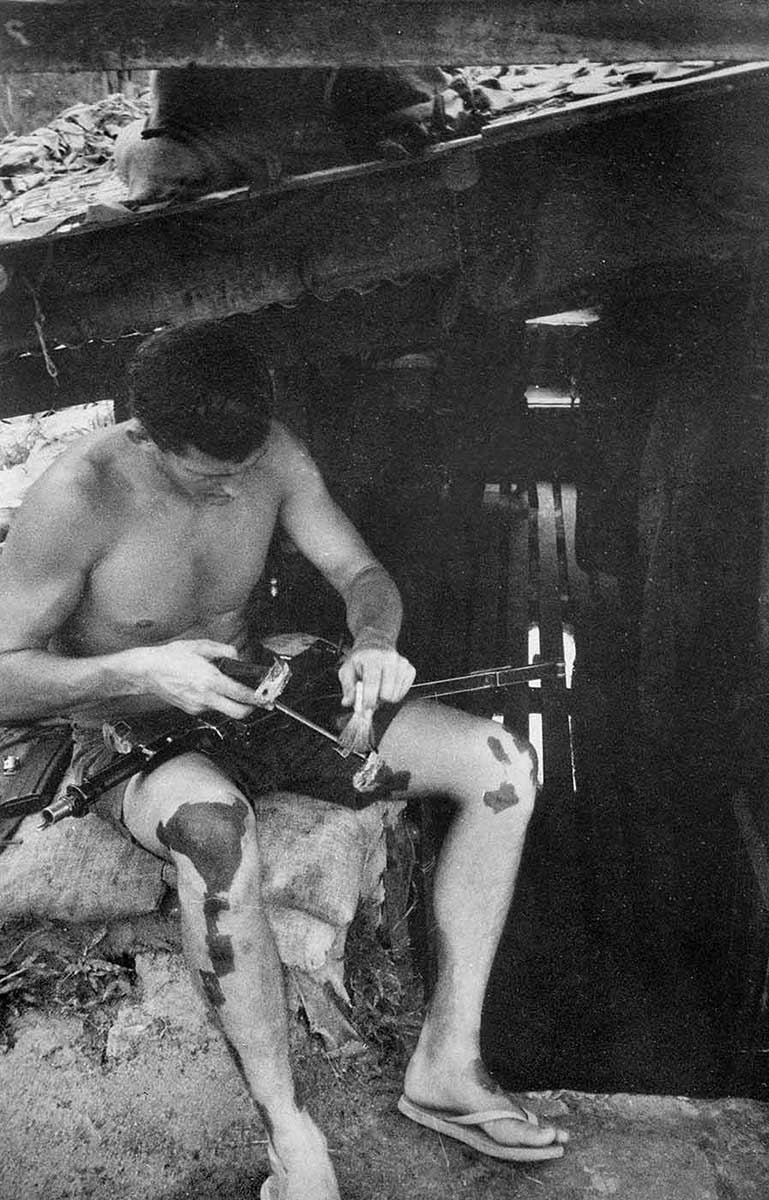

Most of the fighting was done by the SAS and infantry who carried out patrol and ambush operations, and took part in secret incursions across the border into Kalimantan.

Codenamed ‘Claret’, these incursions involved sending small numbers of troops, often by helicopter, into remote jungle to gather intelligence or ambush Indonesian insurgents and regular soldiers.

The Claret infiltrations had to be kept secret because a state of war did not officially exist between Indonesia and the Commonwealth countries. Were it to become public knowledge that Commonwealth troops were fighting on Indonesian soil, it might have forced Indonesia to declare full-scale war, thereby greatly escalating the conflict.

Patrols were under orders to leave no prisoners behind, alive or dead, and to keep out of sight of civilians.

There was no mention of Claret operations in the Australian media. It was not publicly acknowledged in Britain until 1974, and 20 years later in Australia. It is for this reason that Australia’s involvement in the Confrontation is sometimes known as the ‘Forgotten War’.

However, Claret was effective. It kept the Indonesians on the defensive, greatly reducing the number of their incursions into Sabah and Sarawak.

Konfrontasi ends

In March 1966 Sukarno was deposed by General Suharto in a military coup. The new president realised that Indonesia was not going to win the Confrontation. It was also costing the crippled Indonesian economy more than it could afford. On 11 August 1966 Suharto signed a peace treaty with Malaysia.

The death toll stood at 590 Indonesians and 114 Commonwealth troops, including 23 Australians.

Significance

The Confrontation was the last time Australia sent forces to support a British military operation.

However, along with the Malayan Emergency – in which Australia supported British forces in quelling a decade-long communist uprising in Malaya in the 1950s – the Indonesian confrontation was part of a gradual expansion of Australia’s foreign policy into South-East Asia.

Australian military successes in the Malayan Emergency and the Indonesian Confrontation bolstered the Australian Government’s belief that it was possible to successfully wage counterinsurgency warfare in the region. As such, it created the false impression that what could be done at the strategic level in Malaya and Borneo could be replicated in Vietnam.

Explore defining moments

References

Australian involvement in South-East Asian conflicts, Anzac Portal

Indonesian Confrontation, Australian War Memorial

Malaya and Borneo Veterans' Day, Australian Army

Will Fowler, Britain’s Secret War: The Indonesian Confrontation 1962–66, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2006.

Harold James and Denis Sheil-Small, The Undeclared War: The Story of the Indonesian Confrontation 1962–66, Leo Cooper Ltd, London, 1971.