In May 1967, after 10 years of campaigning, a referendum to recognise First Nations peoples in the Australian constitution was held.

The lead-up to the poll focused public attention on the fact that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were treated as second-class citizens.

Nearly 91 per cent of the electorate voted to amend the constitution. This change meant that First Nations peoples would be counted as part of the population and acknowledged as equal citizens, and that the Commonwealth would be able to make laws on their behalf. This was seen to reflect public recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as full Australian citizens.

Gordon Bryant, 1967:

The vote is an overwhelming endorsement of the view that it is time for material action. The Government cannot hide behind constitutional inhibitions, nor can it hide behind a faith in public apathy. This vote represents a great national demand for action.

The history of the 1967 referendum in live-sketch animation, as told by historian David Hunt

First Nations peoples and white law

In the 100 years following 1788, Indigenous people had their homelands and many of their human rights taken away from them by British colonists.

By the end of the 19th century, when the colonies were in the process of federating, First Nations peoples were excluded from almost all aspects of white society and most settler Australians thought of them as a ‘dying race’.

Moreover, 19th-century authorities were hesitant to apply aspects of British colonial law to local population. As Judge Dowling pronounced in the R v Ballard case of 1829: ‘I know of no reason human, or divine, which ought to justify us in interfering with their institutions even if such interference were practicable.'

Therefore, the creators of the constitution paid little consideration to the First Peoples of the land, with only two significant references to them, both exclusionary:

Section 51. The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to:-

... (xxvi) The people of any race, other than the aboriginal people in any State, for whom it is necessary to make special laws.

Section 127. In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives should not be counted.

As historian John Hirst has explained, section 51 (xxvi) meant that the Commonwealth had no power to make laws that specifically applied to First Nations peoples. Only the six states could pass such legislation.

Section 127 excluded First Nations people from being counted in the census for the purpose of determining electoral boundaries. This prevented Queensland and Western Australia, with large Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, from securing more parliamentary seats and tax revenue.

The Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 specifically excluded First Nations people from voting. They were also denied the social security benefits legislated for all other Australians throughout the first half of the 20th century.

Getting organised

The Aborigines Advancement League (AAL) and the New South Wales Aborigines’ Progressive Association (APA) staged a Day of Mourning on Australia Day 1938, the sesquicentenary of British settlement, in commemoration of what activist William Cooper called, ‘the whitemans [sic] seizure of our country’. It was one of the first overtly political actions to highlight the plight of First Nations peoples.

A catalyst for change came in 1956 when a group of Yarnangu people were found to be sick and malnourished in the Warburton Ranges area of the Central Desert. The people’s health, homelands and traditional lifestyles had been affected by nuclear testing conducted by the British and Australian Governments.

The Australian public were outraged when they became aware of the Yarnangu’s condition. Activists from organisations such as AAL and APA mobilised support around the treatment of First Nations peoples and finally the issue reached a broad national audience.

For the first time, Australians broadly expressed a sense of shock at the plight of Aboriginal people.

In 1956 human rights activist Jessie Street highlighted which sections of the constitution were impeding the Commonwealth’s ability to implement policies that would provide financial assistance to First Nations peoples. Street’s recommendations became a key part of the referendum question in 1967.

Various organisations began pressing the government for change. This led to the formation of the first national pressure group, the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement (FCAA), in Adelaide in February 1958. The first two stated goals of the FCAA were:

- Repeal of all legislation, federal and state, which discriminated against the Aboriginal peoples.

- Amendment to Commonwealth Constitution to give the Commonwealth government power to legislate for Aboriginal peoples as with all other citizens …

In 1964 the FCAA recognised Torres Strait Islanders as a distinct people and became the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI).

Early petitions and government action

In the late 1950s and early 1960s activists ran a series of petition drives to gain public support for constitutional change. The FCAA’s 1962–63 nationwide campaign garnered 100,000 signatures.

In May 1964 this brought Arthur Calwell, leader of the Labor Opposition, to table a Bill that called for a referendum to amend section 127 of the constitution. The subsequent debate focused on whether the wording of the section was discriminatory. The Bill did not pass.

Yet, public sentiment was very much for removing the two references in the constitution and Prime Minister Menzies, who had given First Nations peoples the vote in 1962, set a date for a referendum of May 1966.

However, the retirement of Menzies in January 1966 stalled the campaign’s political momentum and under their new leader, Harold Holt, the coalition government postponed the poll.

In February 1967 Attorney-General Nigel Bowden reviewed the situation and recommended to cabinet that the referendum be held soon. Cabinet agreed and a date was set – 27 May 1967.

Campaigning

Unlike most referendums where the central question draws opposing views, the 1967 referendum question of removing the controversial references in the constitution had bipartisan political support and so a national ‘no’ case was not presented.

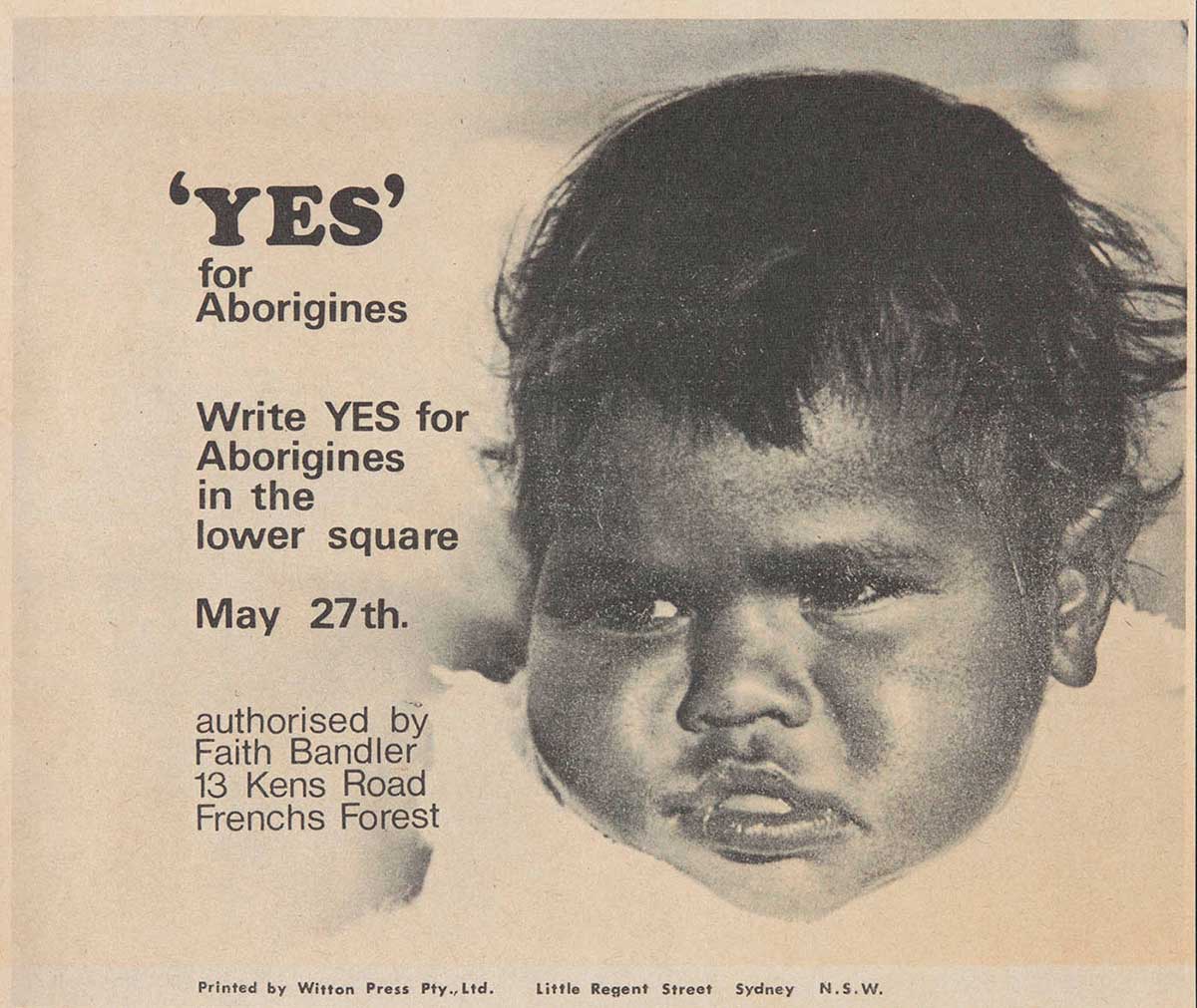

FCAATSI took on the responsibility of campaigning for the ‘yes’ vote, with significant support from unions, churches and the Labor Party.

It framed the campaign in much the same way it had approached the early petition campaigns as a poll on the elimination of discriminatory laws and the institution of civil rights for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population.

FCAATSI believed the 1967 vote for change had to be overwhelming so the government would take their new responsibilities seriously.

A ‘national campaign directorate’ with Kungarakan man Joe McGinness and Labor politician Gordon Bryant as its heads, and Faith Bandler as the New South Wales Coordinator, took leading roles in what became the most successful referendum campaign in Australia’s history

Victory and the aftermath

On 27 May 1967 nearly 91 per cent of Australians voted 'yes' to change the constitution. The huge majority was a validation of 10 years of hard work by First Nations activists. The constitution was formally changed on 10 August that year.

Five months after the referendum, Prime Minister Holt announced the formation of the Council for Aboriginal Affairs. In 1968 the government passed the States Grants (Aboriginal Advancement) Act, which provided federal funds to state governments to support Indigenous communities.

With the election of the Whitlam Labor government in 1972, Gordon Bryant became the first Minister for Aboriginal Affairs supported by an independent department.

The referendum has iconic status in Australian history.

It was the first time the nation came together to show overwhelming support for Indigenous people, and the first time Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were able to mobilise the non-Indigenous population to make that happen. It has also become a benchmark event in imagining how Australia can overcome discrimination against First Nations peoples.

However, as Joe McGinness cautioned supporters in 1967, ‘Winning the referendum is an important step forwards – but it is only a first step.'

Defining Moments in Australian History 24 May 2017

Defining Moments 1967 referendum panel discussion

In our collection

Explore Defining Moments

References

Collaborating for Indigenous Rights 1979–1973

Bain Attwood and Andrew Markus, The 1967 Referendum, Race, Power and the Australian Constitution, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2007.

Faith Bandler, Turning the Tide: A Personal History of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, 1989.

Jack Horner, Seeking Racial Justice: An Insider’s Memoir of the Movement for Aboriginal Advancement, 1938–1978, Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, 2004.