For more than 60 years, Australia has played a vital role in space tracking owing to its geographic location and its technical know-how.

A high point was reached at 12.56pm (AEST) on 21 July 1969 when the Apollo tracking station at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, transmitted live television of Neil Armstrong stepping onto the surface of the moon to a worldwide audience of 600 million (a record for the time).

Today the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex at Tidbinbilla tracks spacecraft voyaging beyond our solar system.

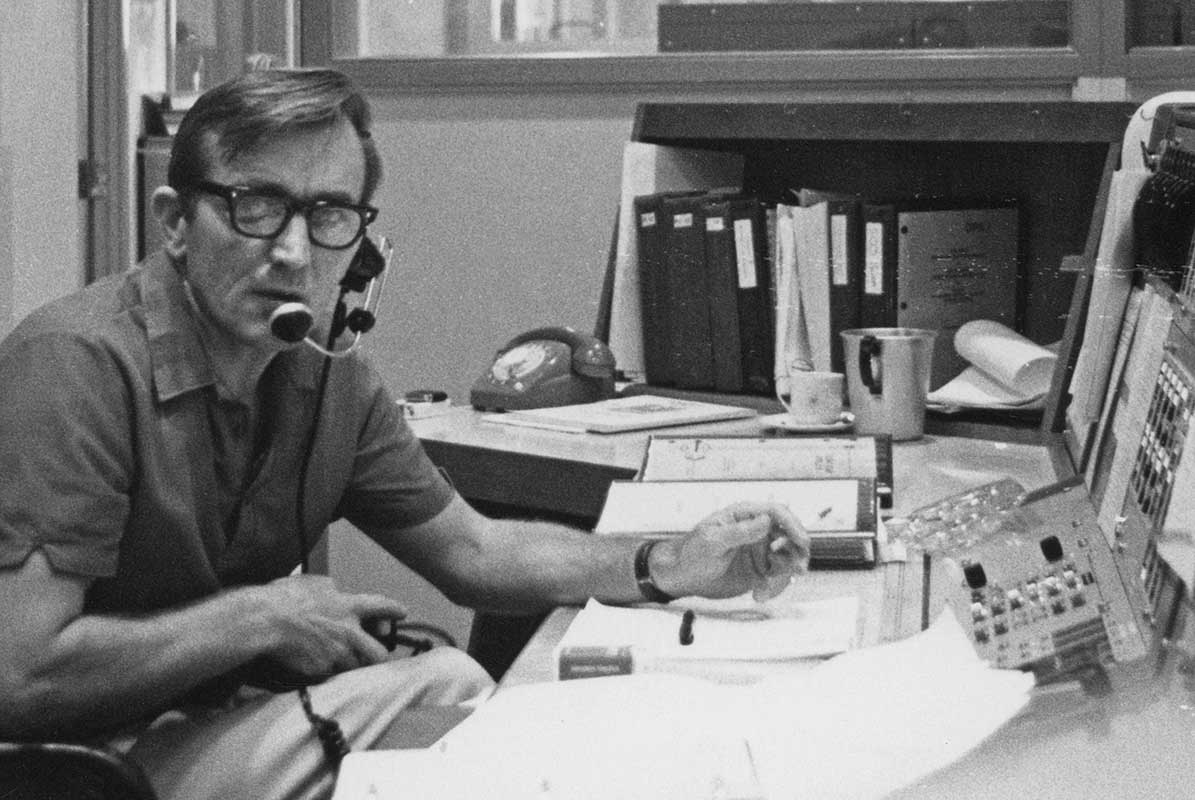

Tom Reid recalling the moment Honeysuckle’s dish brought the world Armstrong’s first step, 1989:

It hadn’t been planned that way, but that’s the way it was. And goddamn it, we were ready!

The space race

The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union entered a new phase in 1957 when the Soviets launched Sputnik, the first human-made object to orbit the earth. This triggered a ‘space race’ between the superpowers.

Australia’s geographic location made it ideal for tracking spacecraft in earth orbit, when travelling to and from the moon, and on voyages into deep space.

In 1964 NASA decided to consolidate its key Australian space tracking stations at sites near Canberra. A station to track human-made objects in deep space was opened at Tidbinbilla in 1965.

Later that same year a second station to track earth-orbiting satellites came online at Orroral Valley.

A third station commenced operations at Honeysuckle Creek in 1967 to track Project Apollo’s manned missions to the moon.

The Apollo tracking stations

NASA’s top priority was to be the first to land a man on the moon. To maximise its astronauts’ safety, three tracking stations were built. These were placed equidistantly around the earth, so that as it spun on its axis, at least one station would have contact with spacecraft on or near the moon.

The first station was built at Goldstone in California and the second near Madrid in Spain. In both, the key jobs were held by Americans. But at the third, Honeysuckle Creek, it was Australian Government policy for all positions to be filled by Australian citizens or permanent residents.

At each site, an 85-foot (26-metre) diameter tracking dish was erected. These dishes generated ultra-high frequency radio uplinks which carried remote commands to the spacecraft and voice from Mission Control.

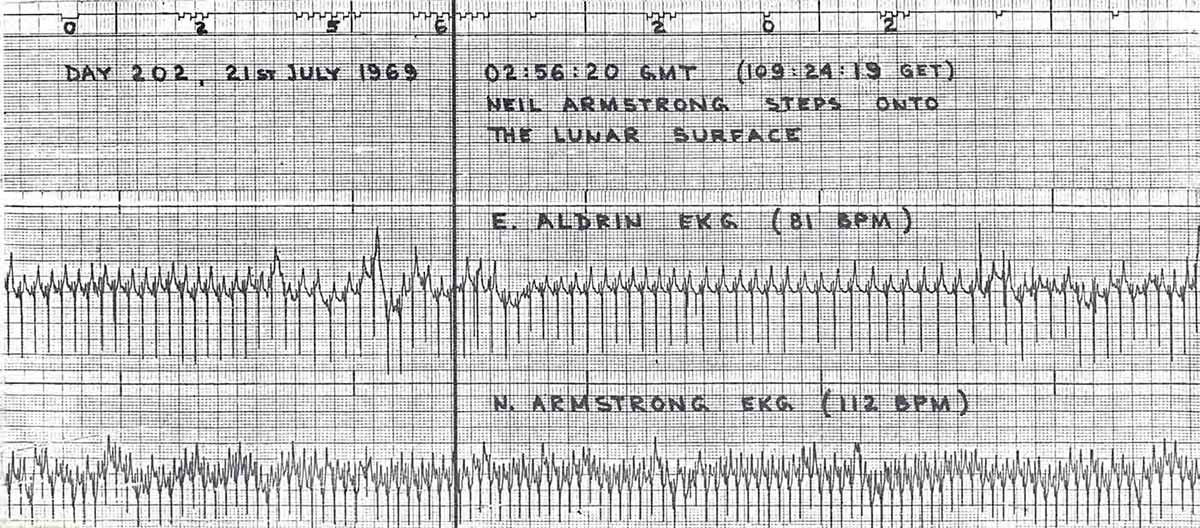

They also received downlinks carrying the astronauts’ voices, data about such things as their heart rates and their spacecraft’s fuel levels, together with their location signals.

Without these special tracking stations, Mission Control in Houston, Texas, would have been effectively deaf, dumb and blind when the Apollo astronauts were near or on the moon.

Honeysuckle Creek

There were no manned moon missions to track during Honeysuckle’s first two years. Sophisticated simulations were therefore used to train the station’s engineers and technicians, but their performance was terrible.

Honeysuckle’s first director was soon replaced by the director of Orroral Valley, Tom Reid, while a new deputy, Mike Dinn, was transferred in from Tidbinbilla.

Within six months, Reid’s firm leadership had taken Honeysuckle Creek from being the worst performing tracking station in the Apollo network to being the best.

For Apollo 11, Honeysuckle tracked the lunar module, Eagle, and its astronauts during their moon walk. In addition, it was the hub station for Tidbinbilla which maintained uplinks and downlinks with the command module, and for the Parkes radio telescope which provided extra receiving capacity for the Eagle’s downlinks.

The near-earth stages of an Apollo mission were covered by a tracking station at Carnarvon in Western Australia.

Armstrong’s first step

At 11.15am (AEST) on Monday 21 July 1969, the moon rose over the Honeysuckle Creek dish which was angled down to zero degrees.

Honeysuckle and Parkes were on the same longitude, but the moon would not rise over the Parkes dish until a little after 1pm because that dish could only be angled down to 30 degrees.

Although Apollo 11’s flight plan had scheduled Armstrong’s first step for around 4pm, Armstrong was given permission to advance this by some hours. And as he emerged from the Eagle sometime after 12.30pm, Goldstone and Honeysuckle had him in view.

On reaching the top of the ladder down to the lunar surface, Armstrong pulled on a lanyard and a small TV camera began remotely filming him from the Eagle’s stowage bay. Because of severe space constraints, the camera had been mounted upside down. At each tracking station, a reversing switch was installed to flip its TV pictures the right way up.

At first, Mission Control broadcast Goldstone’s live TV feed. But Goldstone’s TV technician mucked up his reversing switch. However, Honeysuckle’s TV technician, Ed von Renouard, managed to get it right. So Mission Control switched to Honeysuckle. Seconds later, its live TV transmission of Armstrong stepping onto the moon was broadcast to a then record worldwide audience of 600 million.

A moment or two before Armstrong stepped onto the lunar surface at 12.56pm (AEST), Mission Control switched from the tracking station at Goldstone in California, which was transmitting a faulty TV signal, to the much better images coming from Honeysuckle:

HOUSTON TV: All stations, we have just switched video to Honeysuckle.

A few seconds later, Honeysuckle’s video feed showed Armstrong stepping onto the moon and saying:

That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

Honeysuckle’s TV signal continued going to air around the world for a further six minutes until Parkes’s 210-foot (64-metre) dish came online. Generally speaking, the bigger the dish, the better the picture, and so Parkes’s TV signal was chosen for the remainder of the moon walk.

Legacy

A combination of NASA budget cuts and technological advances led to the eventual closure of Honeysuckle Creek and Orroral Valley, while Parkes has reverted to its role as a radio telescope.

Space tracking was consolidated at Tidbinbilla. This station continues to track human-made objects in deep space, most notably Voyager 2, which has now travelled beyond our solar system.

Australia’s tracking stations have played a vital role in space exploration, with computing being the most notable legacy. A modern mobile phone has many times more computing power than NASA did in 1969. And mobiles around the world are linked by wi-fi – an Australian invention.

In our collection

References

Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station

Hamish Lindsay, Tracking Apollo to the Moon, Springer, London, 2001.

Bryan Sullivan and Jackie French, To the Moon and Back, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 2004.

Andrew Tink, Honeysuckle Creek, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2018.

Sunny Tsiao, ‘Read You Loud and Clear!’: The Story of NASA's Spaceflight Tracking and Data Network, The NASA History Series, Washington DC, 2008.